Lake Victoria

| Lake Victoria | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Primary outflows | White Nile River |

| Catchment area | 184,000 km² 238,900 km² basin |

| Basin countries | Tanzania Uganda Kenya |

| Max. length | 337 km |

| Max. width | 250 km |

| Surface area | 68,800 km² |

| Average depth | 40 m |

| Max. depth | 83 m |

| Water volume | 2,750 km³ |

| Shore length1 | 3,440 km |

| Surface elevation | 1,133 m |

| Islands | 3,000 (Ssese Islands Uganda) |

| Settlements | Bukoba, Tanzania Mwanza, Tanzania Kisumu, Kenya Kampala, Uganda Entebbe, Uganda |

| 1 Shore length is not a well-defined measure. | |

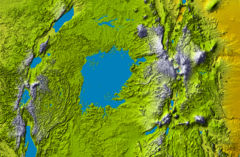

Lake Victoria or Victoria Nyanza (also known as Ukerewe and Nalubaale) is one of the Great Lakes of Africa.

Lake Victoria is 68,800 square kilometres (26,560 mi²) in size, making it the continent's largest lake, the largest tropical lake in the world, and the second widest fresh water lake in the world[1] in terms of surface area (third largest if one considers Lake Michigan-Huron as a single lake). Being relatively shallow for its size, with a maximum depth of 84 m (276 ft) and a mean depth of 40 m (131 ft), Lake Victoria ranks as the seventh largest freshwater lake by volume, containing 2,750 cubic kilometers (2.2 million acre-feet) of water. It is the source of the longest branch of the River Nile, the White Nile, and has a water catchment area of 184,000 square kilometres (71,040 mi²). It is a biological hotspot with great biodiversity. The lake lies within an elevated plateau in the western part of Africa's Great Rift Valley and is subject to territorial administration by Tanzania, Uganda and Kenya. The lake has a shoreline of 3,440 km (2138 miles), and has more than 3,000 islands, many of which are inhabited. These include the Ssese Islands in Uganda, a large group of islands in the northwest of the lake that are becoming a popular destination for tourists.

Lake Victoria is relatively young; its current basin formed only 400,000 years ago, when westward-flowing rivers were dammed by an upthrown crustal block.[2] The lake's shallowness, limited river inflow, and large surface area relative to its volume make it vulnerable to climate changes; cores taken from its bottom show that Lake Victoria has dried up completely three times since it formed.[3] These drying cycles are probably related to past ice ages, which are times when precipitation declined globally.[4] The lake last dried out 17,300 years ago, and filled again beginning 14,700 years ago; the fantastic adaptive radiation of its native cichlids has taken place in the short period of time since then.[5]

Contents |

Exploration history

The first recorded information about Lake Victoria comes from Arab traders plying the inland routes in search of gold, ivory, other precious commodities and slaves. An excellent map, known as the Al Idrisi map from the calligrapher who developed it and dated from the 1160s, clearly depicts an accurate representation of Lake Victoria, and attributes it as the source of the Nile.

The lake was first sighted by a European in 1858 when the British explorer John Hanning Speke reached its southern shore while on his journey with Richard Francis Burton to explore central Africa and locate the Great Lakes. Believing he had found the source of the Nile on seeing this vast expanse of open water for the first time, Speke named the lake after Queen Victoria. Burton, who had been recovering from illness at the time and resting further south on the shores of Lake Tanganyika, was outraged that Speke claimed to have proved his discovery to have been the true source of the Nile, which Burton regarded as still unsettled. A very public quarrel ensued, which not only sparked a great deal of intense debate within the scientific community of the day, but much interest by other explorers keen to either confirm or refute Speke's discovery.

The famous British explorer and missionary David Livingstone failed in his attempt to verify Speke's discovery, instead pushing too far west and entering the River Congo system instead.[6] It was ultimately the Welsh-American explorer Henry Morton Stanley, on an expedition funded by the New York Herald newspaper, who confirmed the truth of Speke's discovery, circumnavigating the lake and reporting the great outflow at Ripon Falls on the lake's northern shore.

Introduction of fish species

The ecosystems of Lake Victoria and its surroundings have been badly affected by human influence. In 1954, the Nile perch (Lates niloticus) was first introduced into the lake's ecosystem in an attempt to improve fishery yields of the lake. Introduction efforts intensified during the very early-1960s. The species was present in small numbers until the early to mid-1980s, when it underwent a massive population expansion and came to dominate the fish community and ecology of the world's largest tropical lake. Also introduced was the Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), now an important food fish for local consumption. The Nile perch (Lates niloticus) proved ecologically and socioeconomically devastating. Together with pollution born of deforestation and overpopulation (of both people and domestic animals), the Nile perch has brought about a massive transformation in the lake's ecosystem and to the disappearance of hundreds of endemic haplochromine cichlid species. Many of these are now presumed to be entirely extinct. A number of other species are extinct in the wild, with populations being maintained in zoos and aquaria, e.g. as part of the Association of Zoos and Aquarium's Species Survival Plan for these species. Some species which were extirpated from Lake Victoria itself, are known to survive in nearby smaller so-called satellite lakes, such as Lake Kyoga, Lake Edward and Lake Albert.

Also vanished from Lake Victoria is one of two native species of tilapia (another kind of cichlid fish), the Singidia tilapia or ngege (Oreochromis esculentus). The ngege is superior in taste and texture to Nile tilapia, but it does not grow as fast or as large and produces fewer young. Ngege and some representatives of haplochromine diversity survive in minute swamp ponds and lakes that dot the Lake Victoria Basin. The initial good returns on Nile perch catches, at their peak delivering export revenues of several hundred million dollars a year, have diminished dramatically due to poor enforcement of fisheries regulations. The proceeds from Nile perch sales remain an important economic engine in the region, but the resulting wealth is very poorly distributed and the overall balance sheet on the Nile perch introduction to Lake Victoria is well into the red despite the enormous value of the perch landings as an export commodity.

The three countries bordering Lake Victoria—Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania —have agreed in principle to the idea of a tax on Nile perch exports, proceeds to be applied to various measures to benefit local communities and sustain the fishery. However, this tax has not been put into force, enforcement of fisheries and environmental laws generally are lax, and the Nile perch fishery remains in essence a mining operation.

Currently, the Nile perch is being overfished. Populations of a few endemic cichlid species have increased again, particularly one to three species of zooplankton-eating, herring-like cichlids (Yssichromis) that school with the abundant native Silver Cyprinid (Rastrineobola argentea), known locally as dagaa (Tanzania), omena (Kenya) or mukene (Uganda). In 1996 The World Bank funded a project to restore and sustain the ecology of Lake Victoria and its fisheries, called LVEMP (Lake Victoria Environmental Management Project).

Meanwhile, the European Union invested another large sum in fisheries infrastructure and monitoring. One product of these foreign aid programmes has been the training of a new generation of East African aquatic ecologists, conservation professionals, and fisheries scientists. There has also been an increase in the fishery research institutes of the lake.

Water lily invasion

The water lily Eichhornia crassipes, a native of the tropical Americas, was introduced by Belgian colonists to Ruanda to beautify their holdings and then advanced by natural means to Lake Victoria where it was first sighted in 1988.[7] There, without any natural enemies, it has become an ecological plague, suffocating the lake, diminishing the fish reservoir, and hurting the local economies. By forming thick mats of vegetation it causes difficulties to transportation, fishing, hydroelectric power generation and drinking water supply. By 1995, 90% of the Ugandan coastline was covered by the plant. With mechanical and chemical control of the problem seeming unlikely, the mottled water hyacinth weevil Neochetina eichhorniae was bred and released with good results. On the Kenyan site, however, neglect has led to significant economic impact making it difficult to reach the harbour of Kisumu, hurting fishing, and threatening the water supply.[7]

Nalubaale Dam

The only outflow for Lake Victoria is at Jinja, Uganda, where it forms the Victoria Nile. The water originally drained over a natural rock weir. In 1952, British colonial engineers blasted out the weir and reservoir. A standard for mimicking the old rate of outflow called the "agreed curve" was established, setting the maximum flow rate at 300 to 1,700 cubic meters per second (392 - 2,224 yd³/sec) depending on the lake's water level.

In 2002, Uganda completed a second hydroelectric complex in the area, with World Bank assistance. By 2006 the water levels in Lake Victoria had reached an 80-year low, and Daniel Kull, an independent hydrologist living in Nairobi, Kenya, calculated that Uganda was releasing about twice as much water as is allowed under the agreement,[8] and was the primary culprit in recent drops in the lake's level. At 55,372 cubic meters per second (35,000 yrd³), more than double the maximum agreed curve, it would take a year to drain 110.75 cubic kilometres (89,500 acre-feet) from the lake. That is approximately 4% of the lake's volume.

Transportation

Since the 1900s Lake Victoria ferries have been an important means of transport between Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya. The main ports on the lake are Kisumu, Mwanza, Bukoba, Entebbe, Port Bell and Jinja. The steamer MV Bukoba sank in the lake on October 3rd, 1995 with a loss of nearly 1,000 lives in one of Africa's worst maritime disasters.

References

- ↑ "LAKE VICTORIA". www.ilec.or.jp. Retrieved on 2008-07-14.

- ↑ Reader, John. Africa. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society, 2001. p. 227

- ↑ Reader, p. 228

- ↑ Reader, p. 228

- ↑ Reader, p. 228

- ↑ "Kenya, Africa - Lake Victoria in Kenya". www.jambokenya.com. Retrieved on 2008-07-14.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Kenia: Die grüne Pest - Politik - SPIEGEL ONLINE - Nachrichten". www.spiegel.de. Retrieved on 2008-07-14.

- ↑ "Uganda pulls plug on Lake Victoria - earth - 09 February 2006 - New Scientist". www.newscientist.com. Retrieved on 2008-07-14.

External links

- Decreasing levels of Lake Victoria Worry East African Countries

- Bibliography on Water Resources and International Law Peace Palace Library

- New Scientist article on Uganda's violation of the agreed curve for hydroelectric water flow.

- Dams Draining Lake Victoria

- Troubled Waters: The Coming Calamity on Lake Victoria multimedia from CLPMag.org

Institutions of the East African Community