Kingdom of Hawaii

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

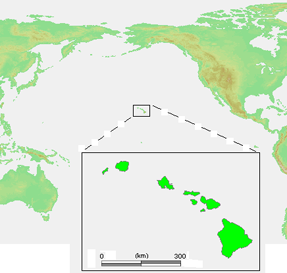

The Kingdom of Hawaiʻi was established during the years 1795 to 1810 with the subjugation of the smaller independent chiefdoms of Oʻahu, Maui, Molokaʻi, Lānaʻi, Kauaʻi and Niʻihau by the chiefdom of Hawaiʻi (or the "Big Island") into one unified government.

Contents |

Formation

Through swift and bloody battles, led by a warrior chief later immortalized as Kamehameha the Great, the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi was established with the help of such British sailors as John Young, Isaac Davis and Alexander Adams and western weapons. Although successful in attacking both Oʻahu and Maui, he failed to secure a victory in Kauaʻi, his effort hampered by a storm. Eventually, Kauaʻi's chief swore allegiance to Kamehameha's rule. The unification ended the feudal society of the Hawaiian islands transforming it into a "modern", independent constitutional monarchy crafted in the tradition of European monarchies.

Government

Government in the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi was transformed in phases, each phase created by the promulgation of the constitutions of 1840, 1852, 1864 and 1887. Each successive constitution can be seen as a decline in the power of the monarch in favor of an elected legislature increasingly dominated by the interests of those of American and European descent.

The head of state and head of government in the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi was the monarch. He or she oversaw the Privy Council which was charged with administration. A royal cabinet, the Privy Council, consisted of ministers in charge of departments much like that of the extant British political system, on which it was based. These ministers also acted as the monarch's primary advisors.

The 1840 Constitution created a bicameral parliament in charge of legislation. The two houses of the legislature were the House of Representatives (directly elected by popular vote) and the House of Nobles (appointed by the monarch with the advice of the Cabinet). The same constitution created a judiciary, charged with overseeing the courts and interpretation of laws. The Supreme Court was led by the Chief Justice, appointed by the monarch with the advice of the Cabinet.

The islands of Hawaiʻi were divided into smaller administrative divisions: Kauaʻi, Oʻahu, Maui, and Hawaiʻi. Kauaʻi region included Niʻihau, while Maui region included Kahoʻolawe, Lānaʻi and Molokaʻi. Each administrative region was governed by a governor appointed by the monarch. See Governor of Oʻahu, Governor of Maui, Governor of Kauaʻi and Royal Governor of Hawaiʻi

Kamehameha Dynasty

From 1810 to 1893, the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi was ruled by two major dynastic families: the Kamehameha Dynasty and the Kalākaua Dynasty. Five members of the Kamehameha family would lead the government as its king. Two of them, Liholiho (Kamehameha II) and Kauikeaouli (Kamehameha III), were direct sons of Kamehameha the Great himself. For a period between Liholiho and Kauikeaouli's reigns, the primary wife of Kamehameha the Great, Queen Kaʻahumanu, ruled as Queen Regent and Kuhina Nui, or Prime Minister.

Dynastic rule by the Kamehameha family tragically ended in 1872 with the death of Lot (Kamehameha V). Upon his deathbed, he summoned Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop to declare his intentions of making her heir to the throne. She was the last direct Kamehameha family member surviving. She refused the crown and throne because she believed that she should help and counsel her people, not rule over them. Lot died before naming an alternative heir.

The Paulet Affair (1843)

On Monday, February 13, 1843, Lord George Paulet, of HMS Carysfort, attempted to annex the islands for alleged insults and malpractices against British subjects.[1] Kamehameha III surrendered to Paulet on February 25, writing:

- Where are you, chiefs, people, and commons from my ancestors, and people from foreign lands?'

- Hear ye! I make known to you that I am in perplexity by reason of difficulties into which I have been brought without cause, therefore I have given away the life of our land. Hear ye! but my rule over you, my people, and your privileges will continue, for I have hope that the life of the land will be restored when my conduct is justified.

- Done at Honolulu, Oahu, this 25th day of February, 1843.

- Kamehameha III.

- Kekauluohi.[2]

Dr. Gerrit P. Judd, a missionary who had become the Minister of Finance for the Kingdom of Hawaii, secretly arranged for General J.F.B. Marshall to be the King's envoy to the United States, France and Britain, to protest Paulet's actions.[3] Marshall was able to secretly convey the Kingdom's complaint to the Vice Consul of Britain in Tepec, posing as a commercial agent of Ladd & Co., a company with friendly relations with the Kingdom.

Marshall's complaint was forwarded to Rear Admiral Thomas, Paulet's commanding officer, who arrived at Honolulu harbor on July 26, 1843 on H.B.M.S. Dublin from Valparaiso, Chile. Admiral Thomas apologized to Kamehameha III for Paulet's actions, and restored Hawaiian sovereignty on July 31, 1843.

Foreign relations

Faced with the quintessential problem of foreign encroachment of Hawaiian territory, King Kamehameha III deemed it prudent and necessary to dispatch a Hawaiian delegation to the United States and then to Europe with the power to settle alleged difficulties with nations, negotiate treaties and to ultimately secure the recognition of Hawaiian Independence by the major powers of the world. In accordance with this view, Timoteo Ha'alilio, William Richards and Sir George Simpson were commissioned as joint Ministers Plenipotentiary on April 8, 1842. Sir George Simpson, shortly thereafter, left for England, via Alaska and Siberia, while Mr. Ha'alilio and Mr. Richards departed for the United States, via Mexico, on July 8, 1842. The Hawaiian delegation, while in the United States of America, secured the assurance of U.S. President John Tyler on December 19, 1842 of its recognition of Hawaiian independence, and then proceeded to meet Sir George Simpson in Europe and secure formal recognition by Great Britain and France. On March 17, 1843, King Louis-Philippe of France recognizes Hawaiian independence at the urging of King Leopold I of Belgium, and on April 1, 1843, Lord Aberdeen on behalf of Her Britannic Majesty Queen Victoria, assured the Hawaiian delegation that, "Her Majesty's Government was willing and had determined to recognize the independence of the Sandwich Islands under their present sovereign."[4][5]

Anglo-Franco Proclamation

On November 28, 1843, at the Court of London, the British and French Governments entered into a formal agreement of the recognition of Hawaiian independence. Called the Anglo-Franco Proclamation, a joint declaration by France and Britain, signed by His Majesty King Louis-Phillipe of the French and Her Britannic Majesty Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom, assured the Hawaiian delegation that:[5]

Her Majesty the Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and His Majesty the King of the French, taking into consideration the existence in the Sandwich Islands (Hawaiian Islands) of a government capable of providing for the regularity of its relations with foreign nations, have thought it right to engage, reciprocally, to consider the Sandwich Islands as an Independent State, and never to take possession, neither directly or under the title of Protectorate, or under any other form, of any part of the territory of which they are composed.

The undersigned, Her Majesty's Principal Secretary of State of Foreign Affairs, and the Ambassador Extraordinary of His Majesty the King of the French, at the Court of London, being furnished with the necessary powers, hereby declare, in consequence, that their said Majesties take reciprocally that engagement.

In witness whereof the undersigned have signed the present declaration, and have affixed thereto the seal of their arms.

Done in duplicate at London, the 28th day of November, in the year of our Lord, 1843.

" 'ABERDEEN. [L.S.]

" 'ST. AULAIRE. [L.S.], [6]

Hawaiʻi was thus the first non-European indigenous state to be admitted into the Family of Nations, while the Ottoman Empire was the first non-Christian nation to be admitted following the Crimean War.[5] This solemn engagement on the part of these two powers was the final act by which the Kingdom of Hawaii was admitted within the pale of civilized nations." The United States notably declined to join with France and England in this statement. Even though President Tyler had recognized Hawaiian Independence, it was not until 1849 that the United States formally recognized Hawaii as a fellow nation.[7]

November 28 was thereafter established as an official national holiday to celebrate the recognition of Hawai'i's independence. As a result of this recognition, the Hawaiian Kingdom entered into treaties with the major nations of the world and had established over ninety legations and consulates in multiple seaports and cities.[5]

Elected monarchy

The refusal of Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop to take the crown and throne as Queen of Hawaiʻi forced the legislature of the Kingdom to declare an election to fill the royal vacancy. From 1872 to 1873, several distant relatives of the Kamehameha line were nominated. In a ceremonial popular vote and a unanimous legislative vote, William C. Lunalilo (1873-1874) became Hawaiʻi's first of two elected monarchs.

Kalākaua Dynasty

Like his predecessor, Lunalilo failed to name an heir to the throne. He died unexpectedly after less than a year as King of Hawaii. Once again, the legislature of the Kingdom of Hawaii declared an election to fill the royal vacancy. Queen Emma, widow of Kamehameha IV, was nominated along with David Kalākaua. The 1874 election was a nasty political campaign in which both candidates resorted to mudslinging and innuendo. David Kalākaua became the second elected King of Hawaii but without the same ceremonial popular vote Lunalilo had. The choice of the legislature was controversial, and U.S. and British troops were called upon to suppress rioting.

Hoping to avoid uncertainty in the monarchy's future, Kalākaua proclaimed several heirs to the throne and defined a royal line of succession. His sister Lili'uokalani would succeed the throne upon Kalākaua's death, with Princess Victoria Kai'ulani to follow. If she could not produce an heir by birth, Prince David Lamea Kawananakoa then Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaole would rule after her.

"Bayonet" Constitution of 1887

In 1887, a constitution was drafted by Lorrin A. Thurston, Minister of Interior under King David Kalākaua. The constitution was proclaimed by the king after a mass meeting of 3,000 residents including an armed militia demanded he sign it or be deposed. The document created a constitutional monarchy like Great Britain's, stripping the King of most of his personal authority, empowering the Legislature and establishing cabinet government. It has since become widely known as the "Bayonet Constitution", a nickname coined by its opponents because of the threat of force used to gain Kalākaua's cooperation.

The 1887 constitution empowered the citizenry to elect members of the House of Nobles (who had previously been appointed by the King). It increased the value of property a citizen must own to be eligible to vote above what the previous Constitution of 1864 had required. One result was to deny voting rights to poor native Hawaiians and Europeans who previously could vote. It guaranteed a voting monopoly to wealthy native Hawaiians and Europeans by denying voting rights to Asians who comprised a large proportion of the population (A few Japanese and some Chinese had previously become naturalized as subjects of the Kingdom and now lost voting rights they had previously enjoyed.) Americans and other Europeans in Hawaiʻi were also given full voting rights without the need for Hawaiian citizenship. The Bayonet Constitution continued allowing the monarch to appoint cabinet ministers, but stripped him of the power to dismiss them without approval from the Legislature.

Overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom

Upon his election in 1874, King Kalākaua had selected Queen Liliʻuokalani as his successor. During her brother's reign the monarchy was left impotent by the 1887 Constitution. Under the pretext of royal corruption, including an opium license bribery scandal, David Kalākaua was forced to sign the constitution stripping the monarchy of much of its power in favor of an administration controlled by the Legislature. Some claim this constitution was the opening salvo to the end of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi.

Liliʻuokalani's Constitution

In 1891, Kalākaua died and his sister Liliʻuokalani assumed the throne. She came to power in the middle of an economic crisis precipitated in part by the McKinley Tariff. By rescinding the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875, the new tariff eliminated the previous advantage Hawaiian sugar exporters enjoyed vis-à-vis other international producers in trade to U.S. markets; the result was a crippling of the Hawaiian sugar industry. Many Hawaiian businesses and citizens were feeling the pressures of the loss of revenue, and Liliʻuokalani proposed a lottery system and opium licensing to bring in additional revenue for the Hawaiian government. Her ministers and closest friends tried to dissuade her from pursuing the bills, and her support was used against her in the looming constitutional crisis.

Liliʻuokalani's chief desire was to restore power to the monarch by abrogating the 1887 Constitution, under which she had come to power after her brother's death. The queen launched a campaign resulting in a petition from some Hawaiian subjects to proclaim a new Constitution. When she informed her cabinet of her plans, they refused to support her.

Those citizens and residents who in 1887 had forced Kalākaua to sign the "Bayonet Constitution" became alarmed when three of her recently appointed cabinet members informed them that the queen was planning to unilaterally proclaim her new Constitution.[8] The cabinet ministers were reported to have feared for their safety after upsetting the queen by not supporting her plans.[9]

The overthrow

In 1893, local businessmen and politicians, primarily of American and European ancestry, in response to the attempt by Liliʻuokalani to abrogate the 1887 constitution, overthrew the queen, her cabinet and her marshal, and took over the government of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi.

There was likely no single motivation behind the coup d'état. Russ suggests that the overthrow was motivated by "the Royal Government under Kalākaua and Liliʻuokalani being inefficient, corrupt, and undependable."[11] Other historians suggest that businessmen were in favor of overthrow and annexation to the U.S. in order to benefit from more favorable trade conditions with its main export market.[12][13][14][15] The proximate cause, however, was a response to Liliʻuokalani's attempt to promulgate a new constitution.

The McKinley Tariff of 1891 eliminated the previously highly favorable trade terms for Hawaii's sugar exports, a main component of the economy. The significance of this economic downturn as a motivation for the overthrow has been questioned by other scholars.[16]

The major events of the overthrow took place between January 15 to January 17, 1893, when 1,500 armed local people, mostly Euro-Americans under the leadership of the thirteen-member Committee of Safety, organized the Honolulu Rifles to depose Queen Liliʻuokalani. They quickly took over government buildings, disarmed the Royal Guard, and declared a Provisional Government.

As these events were unfolding, U.S. Minister John L. Stevens requested that troops be landed. Captain Wiltse of the USS Boston ordered 162 sailors and Marines to come ashore with rifles and Gatling guns, "for the purpose of protecting our legation, consulate, and the lives and property of American citizens, and to assist in preserving public order."[17] Stevens was accused of ordering the landing himself on his own authority, and inappropriately using his discretion. Historian William Russ concluded that "the injunction to prevent fighting of any kind made it impossible for the monarchy to protect itself".[18]

On July 17, 1893, Sanford B. Dole and his committee declared itself the Provisional Government "to rule until annexation by the United States."[19] On July 4, 1894 the Republic of Hawaiʻi was proclaimed. Dole was president of both governments. Later, after a weapons cache was found on the palace grounds after an attempted counter-rebellion in 1895, Queen Liliʻuokalani was placed under arrest, tried by a military tribunal of the Republic of Hawaiʻi, convicted of misprision of treason and then imprisoned in her own home.

The Republic of Hawaiʻi succeeded in its goal when in 1898, Congress approved a joint resolution of annexation creating the U.S. Territory of Hawaiʻi. This followed the precedent of Texas which was also annexed by a joint resolution of Congress. Dole was appointed to be the first governor of the Territory of Hawaiʻi.

The overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi and the subsequent annexation of Hawaiʻi has recently been cited as the first major instance of American imperialism in a book by Stephen Kinzer, a New York Times foreign correspondent.[20]

Royal estates

Early in its history, the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi was governed from several locations including coastal towns on the islands of Hawaiʻi and Maui (Lāhainā). It wasn't until the reign of Kamehameha III that a capital was established in Honolulu on the Island of Oʻahu.

By the time Kamehameha V was king, he saw the need to build a royal palace fitting of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi's new found prosperity and standing with the royals of other nations. He commissioned the building of the palace at Aliʻiōlani Hale. He died before it was completed. Today, the palace houses the Supreme Court of the State of Hawaiʻi.

David Kalākaua shared the dream of Kamehameha V to build a palace, and eagerly desired the trappings of European royalty. He commissioned the construction of ʻIolani Palace from which he and his successor would govern. In later years, the palace would become his sister's makeshift prison under guard by the U.S. Armed Forces, the site of the official raising of the U.S. flag during annexation, and then the site of the territorial governor's and legislature's offices. It is now a museum.

Palaces and Royal Grounds

- Pohukaina Royal Burial Ground of the Hawaiian Royal Family on the Iolani Palace ground

- ʻĀinahau, Home of Princess Victoria Kaʻiulani

- Aliʻiōlani Hale, Originally designed as a Palace for Kamehameha V, although Kamehameha V later decided to convert the building into a government building during construction

- Cathedral Church of Saint Andrew

- Hanaiakamalama, Summer Palace of Queen Emma

- Huliheʻe Palace, Palace of Princess Ruth

- Keōua Hale, Palace of Princess Ruth

- Kaniakapupu, Palace of King Kamehameha III and Queen Kalama

- Muolaulani Palace, Liliuokalani's residence at Kapalama

- ʻIolani Palace, Palace of the Kalākaua Dynasty

- Kawaiahaʻo Church, Westminister Abbey of Hawaiʻi

- Mauna Ala the Royal Mausoleum

- Washington Place, residence of Liliʻuokalani in Honolulu

Notable Hawaiians

Kamehameha Dynasty

- Bernice Pauahi Bishop, Princess of Hawaiʻi

- Kaʻahumanu, Queen Regent of Hawaiʻi

- Kalama Hakaleleponi Kapakuhaili, Queen Consort of Hawaiʻi

- Victoria Kamamalu I, Queen Consort of Hawaiʻi

- Keōpūolani, Queen Mother of Hawaiʻi

- Kinaʻu, Queen Regent of Hawaiʻi

- Kalani Pauahi, Queen Dowager of Hawaiʻi

- Kaʻahumanu III, Queen Consort of Hawaiʻi

- Kalākua Kaheiheimālie, Queen Consort of Hawaiʻi

- Lydia Namahana Piʻia, Queen Dowager of Hawaiʻi

- Victoria Kamamalu II, Princess of Hawaiʻi

- Ruth Keʻelikōlani, Princess of Hawaiʻi

- John William Pitt Kinaʻu, Prince of Hawaiʻi

- Kaʻōanaʻeha Mele, High Chiefess and grandmother of Queen Emma

- Fanny Kekelaokalani Young, High Chiefess and mother of Queen Emma

- Grace Kamaikui Young, High Chiefess and aunt of Queen Emma

- Jane Lahilahi Young, High Chiefess and aunt of Queen Emma

- Emma Rooke, Queen Consort of Hawaiʻi

- Moses Kekuaiwa, Prince of Hawaiʻi

- Albert Kamehameha, Crown Prince of Hawaiʻi

- Kalokuokamaile, Prince of Hawaiʻi

- Gideon Peleʻioholani Laʻanui, Prince of Hawaiʻ

- Gideon Kailipalaki Laʻanui, Prince of Hawaiʻ

- Elizabeth Kekaʻaniau Laʻanui, Princess of Hawaiʻi

- Theresa Owana Kaʻohelelani Laʻanui, Princess of Hawaiʻi

- Laura Kanaholo Kōnia Pauli, Princess of Hawaiʻi

- Abner Pākī, Governor of Hawaiʻi Island and father of Princess Pauahi

- Mataio Kekūanaoʻa, Governor of Oʻahu and consort to two Hawaiian princesses

- Harrieta Keōpūolani Nāhiʻenaʻena, Princess of Hawaiʻi

Kalākaua Dynasty

- Caesar Kapaʻakea, patriach of the Kalakaua Family

- Analea Keohokalole, matriach of the Kalakaua Family

- James Kaliokalani, Prince of Hawaiʻi

- Anna Kaʻiulani, Princess of Hawaiʻi

- Kaiminaʻauao, Princess of Hawaiʻi

- William Pitt Leleiohoku II, Prince of Hawaiʻi

- Miriam K. Likelike, Princess of Hawaiʻi

- Victoria Kaiulani, Princess of Hawaii

- Esther Kapiʻolani, Queen Consort of Hawaiʻi

- Viriginia Kapoʻoloku Poʻomaikelani, Princess of Hawaiʻi

- Captain Hiram Kahanawai, High Chief husband of Poomaikelani

- Victoria Kūhiō Kinoiki Kekaulike, Princess of Hawaiʻi

- David Kahalepouli Piʻikoi, High Chief, husband of Kekaulike

- Jonah Kuhio Kalanianaʻole, Prince of Hawaiʻi

- Elizabeth Kahanu Kalanianaʻole, Princess of Hawaiʻi

- David Kawananakoa, Prince of Hawaiʻi

- Abigail Campbell Kawananakoa, Princess of Hawaiʻi

- Edward Abner Keliʻiahonui, Prince of Hawaiʻi

Authors and artists

- Henri Berger, composer

- Robert Louis Stevenson, author

Civil leaders

- John Kaleipahala Young II Minister of Interior

- John Adams Kuakini, governor and royal brother-in-law

- Charles Reed Bishop, businessman and philanthropist

- James Campbell, businessman and philanthropist

- Archibald Cleghorn, businessman and royal consort

- Sanford B. Dole, chief justice

- Bennet Namekeha, noble

- Jonah Pi'ikoi, noble

- Abner Paki, noble, Supreme Court Justice, and acting governor

- John Owen Dominis, governor and prince consort

- Frank Seaver Pratt, General Council, potential Gov. of Oahu had Emma won royal election, consort of Princess Elizabeth Kekaaniau

- Gerrit P. Judd, royal advisor

- Robert C. Wyllie, Minister of Foreign Affairs

- Kuini Liliha, governor

- George Cox Keʻeaumoku, governor and royal brother-in-law

- Keʻeaumoku Papaiahiahi, govenror, general, Prime Minister and royal father-in-law

- Captain Jack Naihe Kukui, governor and royal pilot

- Boki, governor

- Hoapili, royal advisor, governor, and Commander-in-Chief

- William Pitt Kalanimoku, Commander-in-Chief and Prime Minister

- Lorrin A. Thurston, lawyer and publisher

- Robert William Wilcox, soldier

- John Young ʻOlohana, royal advisor

- Isaac Davis ʻAikake, royal advisor

- Benjamin Dillingham, businessman and industrialist

- Asher B. Bates, Attorney General

- Curtis Iaukea, Secretary of Foreign Affairs

Religious leaders

- Father Damien, Catholic missionary

- Louis Maigret, Catholic bishop

- Thomas Nettleship Staley, Anglican bishop

- Jacob Korchinsky, Russian Orthodox missionary priest

See also

- Committee of Safety (Hawaii), Committee of Safety

- Republic of Hawaii, Republic of Hawaiʻi

- Orthodox Church in Hawaii, History of the Orthodox Christian Church in the Hawaiian Islands

References

- ↑ The US Navy and Hawaii-A Historical Summary

- ↑ The Morgan Report, p500-503

- ↑ La Ku'ko'a: Events Leading to Independence Day, November 28, 1843

- ↑ Hawaiian Kingdom - International Treaties

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Hawaiian Independence Day

- ↑ The Morgan Report, p503-517

- ↑ 503-517 - TheMorganReport

- ↑ Hawaii's Story by Hawaii's Queen, Appendix A "The three ministers left Mr. Parker to try to dissuade me from my purpose; and in the meantime they all (Peterson, Cornwell, and Colburn) went to the government building to inform Thurston and his part of the stand I took."

- ↑ Morgan Report, p804-805 "Every one knows how quickly Colburn and Peterson, when they could escape from the palace, called for help from Thurston and others, and how afraid Colburn was to go back to the palace."

- ↑ U.S. Navy History site

- ↑ The Hawaiian Revolution, by William Russ, Jr. p.349

- ↑ Kinzer, Stephen. (2006). Overthrow: America's Century of Regime Change from Hawaii to Iraq.

- ↑ Stevens, Sylvester K. (1968) American Expansion in Hawaii, 1842-1898. New York: Russell & Russell. (p. 228)

- ↑ Dougherty, Michael. (1992). To Steal a Kingdom: Probing Hawaiian History. (p. 167 - 168)

- ↑ La Croix, Sumner and Christopher Grandy. (March 1997). "The Political Instability of Reciprocal Trade and the Overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom" in The Journal of Economic History 57:161-189.

- ↑ Wiegle, The Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 16, No. 1. (Feb., 1947), p.47 Sugar and the Hawaiian Revolution Richard D. Wiegle wrote in the February 1947 Pacific Historical Review: "In actual fact the planters comprised a vigorous bloc of opinion opposing annexation to the United States, and the key to their attitude lies in their dependence upon contract labor. Annexation to the United States would mean conformity to American immigration legislation and the cessation of the influx of laborers from Asiatic countries so necessary to the life of the plantations.

- ↑ The Morgan Report, p. 834

- ↑ Russ, William Adam. 1992. The Hawaiian Revolution (1893-94). p. 350.

- ↑ Russ, William Adam. 1992. The Hawaiian Revolution (1893-94). p. 90.

- ↑ Overthrow: America's Century of Regime Change From Hawaii to Iraq by Stephen Kinzer, 2006

External links

- Monarchy in Hawaii Part 1

- Monarchy in Hawaii Part 2

- Hawaii a colony or a monarchy

- Early Hawaiian Monarchy

- Mindfulness in Stone Age Hawaii(part II:The Hawaiian Trinity

- Royal Family of Hawaii

- Aliilani

- HAWAIIAN ROYALTY

|

|||||||