Kingdom of England

- "English government" redirects here. For the general topic of the governance of England, see Government of England. For the body that governed England prior to the Union, see Privy Council of England.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

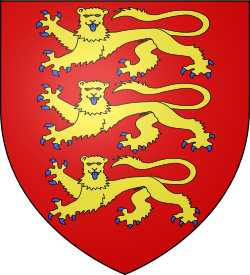

The Kingdom of England was, from 927 to 1707, a state in North-West Europe. The Kingdom of England spanned the southern two-thirds of the island of Great Britain and a number of smaller outlying islands—what is today the legal unit of England and Wales. England as a unified state traces its origins to the 9th or 10th century, and was united with the neighbouring Kingdom of Scotland to create the the Kingdom of Great Britain, under the terms of the Acts of Union 1707.

The chief royal residence was originally located at Winchester, in Hampshire, but Westminster and Gloucester were accorded almost equal status—especially Westminster. The City of Westminster, had become the de facto capital by the beginning of the 12th century. London served as the capital of the kingdom until its merger with the Kingdom of Scotland in 1707 and continues to remain the capital of England. London has also served as the capital of both the Kingdom of Great Britain (1707–1801) and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (1801–1922). Today it remains the capital of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (the "United Kingdom").

The present monarch of the United Kingdom, Queen Elizabeth II, is the modern successor to the Kings and Queens of England. The title of Queen (and King) of England has been legally incorrect since 1604, although it is still in common use. Elizabeth can trace her descent from the Kings of Wessex of the 1st millennium.

Contents |

History

The Kingdom of England has no specific founding date. The Kingdom can trace its origins to the Heptarchy, the rule of what would later become England by seven minor Kingdoms: East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Mercia, Northumbria, Sussex, and Wessex. The Anglo-Saxons themselves, for example in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, called their lands "this Anglian land of Britain" which referred to the ancient Roman provinces of Britain, not to the whole island.

The most powerful of the Kings of any of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms was quite frequently acknowledged as the Bretwalda, a kind of high king over the other kings. The famous rowing of the boat on the River Dee was meant to symbolise this relationship as the Bretwalda was at the helm, while the other kings took the oars.

The Kings of Wessex, who conquered Kent and Sussex from Mercia in 825, became increasingly dominant over the other kingdoms of England during the 9th century. The conquest of Northumbria, East Anglia and half of Mercia by the Danes left Alfred the Great (reigned 871–899) of Wessex as the only surviving English king. He successfully resisted a series of Danish invasions and brought the remaining half of Mercia under the sovereignty of Wessex. His son Edward the Elder (reigned 899–924) completed the absorption of English Mercia and conquered the rest of Mercia and East Anglia from their Danish occupiers, uniting England south of the Humber. In 927 Northumbria, whose Danish kings had recently been displaced by Norwegians, fell to the King of Wessex Athelstan, a son of Edward the Elder. Athelstan was the first to reign over a united England. He was not the first de jure King of England, but certainly the first de facto one. Over the following years Northumbria repeatedly changed hands between the English kings and Norwegian invaders, but was definitively brought under English control by King Edred in 954, completing the unification of England.

England has remained in political unity ever since. During the reign of Ethelred II (reigned 978–1016) a new wave of Danish invasions orchestrated by Sweyn I of Denmark culminated, after a quarter of a century of warfare, in the conquest of England in 1013. Sweyn died on 2 February 1014 and Ethelred was restored to the throne, but in 1015 Sweyn's son Canute the Great launched a new invasion. The ensuing war ended in 1016 with an agreement between him and Ethelred's successor Edmund Ironside to divide England between them, but Edmund's death on 30 November 1016 left England united under Danish rule. Danish rule continued until the death of Harthacanute on 8 June 1042. He was a son of Canute and Emma of Normandy, widow of Ethelred II. Harthacanute had no heirs of his own and was succeeded by his half-brother Edward the Confessor. The Kingdom of England was independent again.

Norman conquest

Peace only lasted until the death of childless Edward on 5 January, 1066. His brother-in-law was crowned Harold II of England. His cousin William the Bastard, Duke of Normandy, immediately claimed the throne for himself. William launched an invasion of England and landed in Sussex on 28 September 1066. Harold II and his army were in York following their victory in the Battle of Stamford Bridge (25 September 1066). They had to march across England to reach their new opponents. The armies of Harold II and William finally faced each other in the Battle of Hastings (14 October 1066). Harold fell and William emerged the victor. William was then able to conquer England with little further opposition. He was not, however, planning to absorb the Kingdom to the Duchy of Normandy. As a Duke, William still owed allegiance to Philip I of France. The independent Kingdom of England would allow him to rule without interference. He was crowned King of England on 25 December 1066.

The Kingdom of England and the Duchy of Normandy would remain in personal union until 1204. King John of England, a fourth-generation descendant of William I, lost the continental area of the Duchy to Philip II of France during that year. A few remnants of Normandy, which included the Channel Islands, remained in the possession of King John, as did most of the Duchy of Aquitaine.

Norman conquest of Wales

Up to the time of the Norman conquest of Anglo-Saxon England, Wales had remained for the most part independent of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, although some Welsh kings did sometimes acknowledge the Bretwalda, for example.

However, soon after the Norman conquest of England, some of the Norman lords began to attack Wales and conquered parts of it, which they ruled, acknowledging the overlordship of the Norman kings of England, but with considerable local independence. Over many years these "Marcher Lords" conquered more and more of Wales, with considerable resistance led by various Welsh princes, who also often acknowledged the overlordship of the Norman kings of England.

King John's grandson Edward I of England defeated Llywelyn the Last and effectively conquered Wales in 1282. He created the title Prince of Wales for his eldest son Edward II in 1301. While Edward's conquest was brutal and later repression considerable, as the magnificent Welsh castles, such as Conwy, Harlech and Caernarfon attest, this event re-united under the same ruler the lands of Roman Britain for the first time since the establishment of the Jutes in Kent in the 5th century AD some 700 years before.

This was a highly significant moment in the history of medieval England as it re-established links with the pre-Anglo-Saxon past. These links were exploited for political purposes to unite the peoples of the kingdom, including the Anglo-Normans, by popularising Welsh legends.

However, the Welsh language, derived from the common British language with significant Latin influence, continued to be spoken by the majority of the population of Wales for at least another 500 years.

Loss of the Angevin Empire and the Wars of the Roses

Edward II was father to Edward III of England, whose claim to the throne of France resulted in the Hundred Years' War (1337–1453). The end of the war found England defeated and retaining only a single city of France: Calais.

During the Hundred Years War an English identity was seen to develop, contrasting with the previous split between the Norman Lords and their Anglo-Saxon subjects, in the context of the sustained hostility to the increasingly nationalist French whose kings and other leaders notably the charismatic Joan of Arc used a developing sense of French identity to help to draw people to their cause. The Anglo-Norman became separate from their cousins who held lands mainly in France who mocked them for their archaic and bastardised spoken French. English also became the language of the law courts during this period.

The Kingdom had little time to recover before entering the Wars of the Roses (1455–1487), a series of civil wars over possession of the throne between the House of Lancaster and the House of York, different branches of the descendants of Edward III. The end of the wars found the throne held by a female line descendant of the House of Lancaster married to the eldest daughter of the House of York. Henry VII of England and his Queen consort Elizabeth of York were the founders of the Tudor dynasty which ruled the Kingdom from 1485 to 1603.

Tudors and Stuarts

Meanwhile, Wales retained the distinct legal and administrative system that had been established by Edward I in the late 13th century. The second of the Welsh origin Tudor dynasty, Henry VIII of England, merged Wales into England under the Laws in Wales Acts 1535-1542. Wales ceased to be a personal fiefdom of the King of England but was annexed to the Kingdom of England and was represented in the Parliament of England.

During Henry VIII's reign in 1541 the Parliament of Ireland proclaimed him King of Ireland, thus bringing the Kingdom of Ireland into personal union with the Kingdom of England.

During the reign of Mary I of England, eldest daughter of Henry VIII, Calais was captured by Francis, Duke of Guise on 7 January 1558.

The House of Tudor ended with the death of its last monarch, Elizabeth I of England, on 24 March 1603. Without any direct heir to her throne, James VI, King of Scots, a descendant of Margaret Tudor, Henry VIII's sister, from Scotland's Stuart dynasty, ascended the throne of England as Elizabeth's heir, and King James I of England. He was Protestant. Despite this Union of the Crowns, the Kingdom of England and Kingdom of Scotland remained separate and independent states under this personal union, until 1707.

In 1707, the Acts of Union ratified by both the Parliament of Scotland and Parliament of England created the Kingdom of Great Britain (1707–1801). Queen Anne, the last monarch from the House of Stuart, became the first monarch of the new kingdom. Both the English and Scottish Parliaments were merged into the Parliament of Great Britain, located in Westminster, London. At this point, England ceased to exist as a separate political entity and has since had no national government. Legally, however, the jurisdiction continued to operate as England and Wales (just as Scotland continued to have its own laws and law courts) and this continued also after the Act of Union of 1800 between the Kingdom of Great Britain and Kingdom of Ireland which created the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. (Later going on to become the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland).

Commonwealth and Protectorate

England was a monarchy for the entirety of its political existence since its creation about 927 up to the 1707 Act of Union, except for the eleven years of English Interregnum (1649 to 1660) that followed the English Civil War.

The rule of executed King Charles I of England was replaced by that of a republic known as Commonwealth of England (1649–1653). The most prominent general of the republic, Oliver Cromwell, managed to extend its rule to Ireland and Scotland.

The victorious general eventually turned against the republic, and established a new form of government known as The Protectorate, with himself as Lord Protector until his death on 3 September 1658. He was succeeded by his son Richard Cromwell. However, anarchy eventually developed, as Richard proved unable to maintain his rule. He resigned his title and retired into obscurity. The Commonwealth was re-established but proved unstable. The exiled claimant Charles II of England was recalled to the throne in 1660 in the English Restoration.

References

See also

- List of monarchs of England

- Royal Navy

- Crown Jewels of England

- England and Wales

- Kingdom of Cornwall (Kernow)

- Anglo-Norman language

| Preceded by The Heptarchy c.500 – c.927 |

Kingdom of England c.927 – 1649 |

Succeeded by English Interregnum 1649 – 1660 |

| Preceded by English Interregnum 1649 – 1660 |

Kingdom of England 1660 – 1707 |

Succeeded by Kingdom of Great Britain 1707 – 1800 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||