Kidney

| Kidney | |

|---|---|

|

|

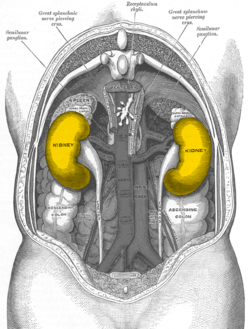

| Human kidneys viewed from behind with spine removed | |

|

|

| Lamb kidneys | |

| Latin | ren |

| Gray's | subject #253 1215 |

| Artery | renal artery |

| Vein | renal vein |

| Nerve | renal plexus |

| MeSH | Kidney |

| Dorlands/Elsevier | Kidney |

The kidneys are complicated organs that have numerous biological roles. Their primary role is to maintain the homeostatic balance of bodily fluids by filtering and secreting metabolites (such as urea) and minerals from the blood and excreting them, along with water, as urine. Because the kidneys are poised to sense plasma concentrations of ions such as sodium, potassium, hydrogen, oxygen, and compounds such as amino acids, creatinine, bicarbonate, and glucose, they are important regulators of blood pressure, glucose metabolism, and erythropoiesis (the process by which red blood cells (erythrocytes) are produced). The medical field that studies the kidneys and diseases of the kidney is called nephrology[1]. The prefix nephro- meaning kidney is from the Ancient Greek word nephros (νεφρός); the adjective renal meaning related to the kidney is from Latin rēnēs, meaning kidneys. [2]

Contents |

Anatomy

In humans, the kidneys are located in the posterior part of the abdominal cavity. There are two, one on each side of the spine; the right kidney sits just below the diaphragm and posterior to the liver, the left below the diaphragm and posterior to the spleen. Above each kidney is an adrenal gland (also called the suprarenal gland). The asymmetry within the abdominal cavity caused by the liver results in the right kidney being slightly lower than the left one while the left kidney is located slightly more medial. The bulk of water re-absorption in the vertebrate kidney takes place in the loop of Henle.

The kidneys are retroperitoneal and range from 9 to 13 cm in diameter; the left slightly larger than the right. They are approximately at the vertebral level T12 to L3. The upper parts of the kidneys are partially protected by the eleventh and twelfth ribs, and each whole kidney and adrenal gland are surrounded by two layers of fat (the perirenal and pararenal fat) and the renal fascia which help to cushion it. Congenital absence of one or both kidneys, known as unilateral (on one side) or bilateral (on both the sides) renal agenesis, can occur.

The kidneys receive unfiltered blood directly from the heart through the abdominal aorta which then branches to the left and right renal arteries. Filtered blood then returns by the left and right renal veins to the inferior vena cava and then the heart. Renal blood flow accounts for 20-25% of the cardiac output.

Functions

Blood Filtering

First, the blood enters through the glomerulus. it then passes through the renal tubules being filterred and reabsorbed to the collecting duct through which the byproduct of the filtration passes into the ureters in the form of urine.

Excretion of waste products

The kidneys excrete a variety of waste products produced by metabolism, including the nitrogenous wastes: urea (from protein catabolism) and uric acid (from nucleic acid metabolism) and water.

Homeostasis

The kidney is one of the major organs involved in whole-body homeostasis. Among its homeostatic functions are acid-base balance, regulation of electrolyte concentrations, control of blood volume, and regulation of blood pressure. The kidneys accomplish these homeostatic functions independently and through coordination with other organs, particularly those of the endocrine system. The kidney communicates with these organs through hormones secreted into the bloodstream.

Acid-base balance

The kidneys regulate the pH of blood by adjusting H+ ion levels, referred as augmentation of mineral ion concentration, as well as water composition of the blood.

Blood pressure

Sodium ions are controlled in a homeostatic process involving aldosterone which increases sodium ion reabsorption in the distal convoluted tubules.

Plasma volume

Any significant rise or drop in plasma osmolality is detected by the hypothalamus, which communicates directly with the posterior pituitary gland. A rise in osmolality causes the gland to secrete antidiuretic hormone, resulting in water reabsorption by the kidney and an increase in urine concentration. The two factors work together to return the plasma osmolality to its normal levels.

Hormone secretion

The kidneys secrete a variety of hormones, including erythropoietin, urodilatin, and the activated form of vitamin D.

Embryology

The mammalian kidney develops from intermediate mesoderm. Kidney development, also called nephrogenesis, proceeds through a series of three successive phases, each marked by the development of a more advanced pair of kidneys: the pronephros, mesonephros, and metanephros.[3] (The plural forms of these terms end in -oi.)

Pronephros

During approximately day 22 of human gestation, the paired pronephroi appear towards the cranial end of the intermediate mesoderm. In this region, epithelial cells arrange themselves in a series of tubules called nephrotomes and join laterally with the pronephric duct, which does not reach the outside of the embryo. Thus the pronephros is considered nonfunctional in mammals because it cannot excrete waste from the embryo.

Mesonephros

Each pronephric duct grows towards the tail of the embryo, and in doing so induces intermediate mesoderm in the thoracolumbar area to become epithelial tubules called mesonephric tubules. Each mesonephric tubule receives a blood supply from a branch of the aorta, ending in a capillary tuft analogous to the glomerulus of the definitive nephron. The mesonephric tubule forms a capsule around the capillary tuft, allowing for filtration of blood. This filtrate flows through the mesonephric tubule and is drained into the continuation of the pronephric duct, now called the mesonephric duct or Wolffian duct. The nephrotomes of the pronephros degenerate while the mesonephric duct extends towards the most caudal end of the embryo, ultimately attaching to the cloaca. The mammalian mesonephros is similar to the kidneys of aquatic amphibians and fishes.

Metanephros

During the fifth week of gestation, the mesonephric duct develops an outpouching, the ureteric bud, near its attachment to the cloaca. This bud, also called the metanephrogenic diverticulum, grows posteriorly and towards the head of the embryo. The elongated stalk of the ureteric bud, the metanephric duct, later forms the ureter. As the cranial end of the bud extends into the intermediate mesoderm, it undergoes a series of branchings to form the collecting duct system of the kidney. It also forms the major and minor calyces and the renal pelvis.

The portion of undifferentiated intermediate mesoderm in contact with the tips of the branching ureteric bud is known as the metanephrogenic blastema. Signals released from the ureteric bud induce the differentiation of the metanephrogenic blastema into the renal tubules. As the renal tubules grow, they come into contact and join with connecting tubules of the collecting duct system, forming a continuous passage for flow from the renal tubule to the collecting duct. Simultaneously, precursors of vascular endothelial cells begin to take their position at the tips of the renal tubules. These cells differentiate into the cells of the definitive glomerulus.

Terms

- renal capsule: The membranous covering of the kidney.

- cortex: The outer layer over the internal medulla. It contains blood vessels, glomeruli (which are the kidneys' "filters") and urine tubes and is supported by a fibrous matrix.

- hilum: The opening in the middle of the concave medial border for nerves and blood vessels to pass into the renal sinus.

- renal column: The structures which support the cortex. They consist of lines of blood vessels and urinary tubes and a fibrous material.

- renal sinus: The cavity which houses the renal pyramids.

- calyces: The recesses in the internal medulla which hold the pyramids. They are used to subdivide the sections of the kidney. (singular - calyx)

- papillae: The small conical projections along the wall of the renal sinus. They have openings through which urine passes into the calyces. (singular - papilla)

- renal pyramids: The conical segments within the internal medulla. They contain the secreting apparatus and tubules and are also called malpighian pyramids.

- renal artery: Two renal arteries come from the aorta, each connecting to a kidney. The artery divides into five branches, each of which leads to a ball of capillaries. The arteries supply (unfiltered) blood to the kidneys. The left kidney receives about 60% of the renal bloodflow.

- renal vein: The filtered blood returns to circulation through the renal veins which join into the inferior vena cava.

- renal pelvis: Basically just a funnel, the renal pelvis accepts the urine and channels it out of the hilus into the ureter.

- ureter: A narrow tube 40 cm long and 4 mm in diameter. Passing from the renal pelvis out of the hilus and down to the bladder. The ureter carries urine from the kidneys to the bladder by means of peristalsis.

- renal lobe: Each pyramid together with the associated overlying cortex forms a renal lobe

Medical terminology

- Medical terms related to the kidneys involve the prefixes renal- and nephro-.

- Surgical removal of the kidney is a nephrectomy, while a radical nephrectomy is removal of the kidney, its surrounding tissue, lymph nodes, and potentially the adrenal gland. A radical nephrectomy is performed for the removal of the cancers.

Diseases and disorders

Congenital

- Congenital hydronephrosis

- Congenital obstruction of urinary tract

- Duplicated ureter

- Horseshoe kidney

- Polycystic kidney disease

- Renal dysplasia

- Unilateral small kidney

- Multicystic dysplastic kidney

Acquired

- Diabetic nephropathy

- Glomerulonephritis

- Hydronephrosis is the enlargement of one or both of the kidneys caused by obstruction of the flow of urine.

- Interstitial nephritis

- Kidney stones are a relatively common and particularly painful disorder.

- Kidney tumors

- Wilms tumor

- Renal cell carcinoma

- Lupus nephritis

- Minimal change disease

- In nephrotic syndrome, the glomerulus has been damaged so that a large amount of protein in the blood enters the urine. Other frequent features of the nephrotic syndrome include swelling, low serum albumin, and high cholesterol.

- Pyelonephritis is infection of the kidneys and is frequently caused by complication of a urinary tract infection.

- Renal failure

- Acute renal failure

- Stage 5 Chronic Kidney Disease

The failing kidney

Generally, humans can live normally with just one kidney, as one has more functioning renal tissue than is needed to survive. Only when the amount of functioning kidney tissue is greatly diminished will Stage 5 Chronic Kidney Disease develop. If the glomerular filtration rate (a measure of renal function) has fallen very low ( Stage 5 Chronic Kidney Disease), or if the renal dysfunction leads to severe symptoms, then renal replacement therapy is indicated, either dialysis or kidney transplantation.

Histology

Human cell types found in the kidney include:

- Kidney glomerulus parietal cell

- Kidney glomerulus podocyte

- Kidney proximal tubule brush border cell

- Loop of Henle thin segment cell

- Thick ascending limb cell

- Kidney distal tubule cell

- Kidney collecting duct cell

- Cortical collecting duct cell

- Medullary collecting duct cell

- Interstitial kidney cell, which do not participate in the filtration process.[4]

History of human thought about kidneys

The Latin term renes is related to the English word "reins", a synonym for the kidneys in Shakespearean English (eg. Merry Wives of Windsor 3.5), which was also the time the King James Version was translated. Kidneys were once popularly regarded as the seat of the conscience and reflection[5][6], and a number of verses in the Bible (eg. Ps. 7:9, Rev. 2:23) state that God searches out and inspects the kidneys, or "reins", of humans. Similarly, the Talmud (Berakhoth 61.a) states that one of the two kidneys counsels what is good, and the other evil.

Animal kidneys as food

The kidneys of animals can be cooked and eaten by humans (along with other offal). If prepared properly, they can be nutritious and pleasant tasting. Veal kidneys and lamb kidneys are particularly prized for their tenderness and flavour. Kidneys can be grilled or sautéed, though they become tough and unpleasant if overcooked.

See also

- Kidney stone

- Kidney transplantation

- Renal physiology

- Urinary system

References

- ↑ "Nephrology". Dictionary.com. Retrieved on 2007-08-04.

- ↑ Maton, Anthea; Jean Hopkins, Charles William McLaughlin, Susan Johnson, Maryanna Quon Warner, David LaHart, Jill D. Wright (1993). Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-981176-1.

- ↑ Bruce M. Carlson (2004). Human Embryology and Developmental Biology (3rd edition ed.). Saint Louis: Mosby. ISBN 0-323-03649-X.

- ↑ mednote.co

- ↑ The Patient as Person: Explorations in Medical Ethics p. 60 by Paul Ramsey, Margaret Farley, Albert Jonsen, William F. May (2002)

- ↑ History of Nephrology 2 p. 235 by International Association for the History of Nephrology Congress, Garabed Eknoyan, Spyros G. Marketos, Natale G. De Santo - 1997; Reprint of American Journal of Nephrology; v. 14, no. 4-6, 1994.

External links

- electron microscopic images of the kidney (Dr. Jastrow's EM-Atlas)

- European Renal Genome project kidney function tutorial

- Kidney Foundation of Canada kidney disease information

- National Kidney Foundation

- Kidney Foundation (Canada)

- BC Renal Agency - Official site for the province-wide network of renal care providers in British Columbia, Canada

- World Kidney Day website

- UNC Nephropathology

- Information on kidneys

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||