Kemenche

|

|

| Classification | *Bowed string instrument |

|---|---|

| Other names | ç’ilili(ჭილილი), Pontic kemenche |

| Related instruments | * Rebec

|

A kemenche (Turkish: kemençe, Laz: Ç'ilili(ჭილილი), Greek: κεμεντζές) is a bottle-shaped, 3-stringed type of rebec or fiddle from the Black Sea region of Asia Minor also known as the "kementche of Laz" in Turkey. In Greece and the Pontian Greek diaspora, it is known as the "Pontian lyra". It is the main instrument used in Pontian music. The kemenche is played in the upright position, either by resting it on the knee when sitting, or held in front of the player when standing. The kemenche bow is called the doksar.

Contents |

Pontic kemenche

Many folk fiddles ranging from Southeastern Europe to the Indian sub-continent are played by the lateral pressure of the finger nails of the player’s hand against the strings with the instrument generally being held facing outwards. This would include the Indian sarangi and the Bulgarian gadulka. Other fiddles played by pressure of the pads of the fingers upon the strings as is also done with some lyras which have the third or even the second string positioned in such a way so as not to allow the easy insertion of the finger between the strings and the spike fiddles, and there are those lyras whose strings are depressed onto the neck of the instrument by the player’s finger pads in the way violin strings are pressed such as an unusual type of Dodecanesian lyra with four strings, the large Cappadocian kemanes, and the kemenche. It may be that the old dancing master’s kit or pochette fiddle one form of which outwardly resembles the Pontic lyra, was adapted and developed later in isolation in Pontos led to the present form of kemenche. On the other hand, the kemenche may be result of the natural development of an instrument which had, at once time, an elongated water gourd for its body. Compare the from south Afghina with the kemenche/Pontic lyra.

The center of lyra playing activity seems to have been the district of Trabzon and the contiguous areas of the districts to the west and east of it as well as to the south, Giresun, Rize, and Gümüşhane whose main town was Arghyrόpolis. As one moves west past Tirebolu towards Kerasounta/Giresun, the number of lyra players begins to decrease and the lute as well as the violin (keman) and tambourine (tef) begin playing a more important role in Pontic music. Further west into the districts of the Kotyora/Ordu and before reaching the town of Samsun the lyra has virtually disappeared so that Bafra, whose inhabitants were Turkish speaking Pontics, one finds the violin (kemane), clarinet (gırnata), lute (Oud), and bass drum (davul) as the main musical instruments, Sinope/Sinop and its environs is not usually considered in recent tradition.

Moving east of Trabzon, the picture is much the same. After Rize, the kemenche being facing competition from the bagpipes (Pontic dankiyo/tulum)).

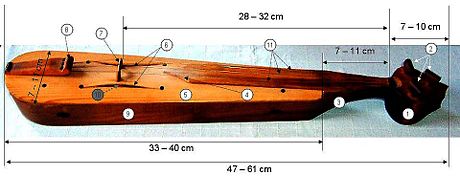

| # | Part Name | Meaning | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tepe, To Kifal | Top, Head | Peg holder (same as the body) |

| 2 | Kulak, Otia | Fist, Ears | Pegs |

| 3 | Boyun, Goula | Neck | Place for hand (same as the body) |

| 4 | Kravat, Spaler | Bed, Slabbering bib | Fingerboard |

| 5 | Kapak | Cover | Soundboard |

| 6 | Ses delikleri, Rothounia | Sound holes, Nostrals | Soundholes |

| 7 | Eşek, Gaidaron | Donkey, Rider | Bridge (pine) |

| 8 | Palikar | Stalward Young Man | Tailpiece |

| 9 | Gövde, Soma | Body | Body (plum, mulberry, walnut, juniper) |

| 10 | Solucan, Stoular | Worm | Sound post (inside) |

| 11 | Teller, Hordes | Strings | Strings |

Tuning

The lyra usually has three strings which have several tunings. Common tunings include: a-a-d, e-a-d, and many others in 4ths (the strings are of 2 octaves ... La, Mi, Ci). Since the instrument was often played alone, the tuning was often done according to the preference of the musician and his voice's range.

The musicians usually play two or all three strings at the same time, utilizing the open string(s) as a sort of drone to the melody. Sometimes they play the melody on two strings at once, giving a primitive harmony in fourths. They tend to play with many trills and embellishments, and with the unusual harmonies. Old strings were made from dried entrails but now metal strings are used (guitar and violin)

Kemane

"KEMANE" had been the musical instrument in the area of Ata-Pazar-Poulantzaki-Ortou-Kerasounta in the Black Sea. According to Mrs Sofia Theodoridou from Drepano Kozanis, aged 93, in Greece, "KEMANE" is being played in the village "Akrini" in the area of Kozani, as well as in "Plati" in the area of Hmathia by Kapadokes (the people whose origins are located in Kappadokia (a wide area in Asia Minor).

According to musicological researches, as far as all objects of materia! civilization are concerned, it is the musical instrument in general that has travelled the most.

The great historian and theorist of Arabic music, Mr. El Farabi (10th century), in his research regarding Medieval instruments in the East, he mentions instruments used to be common in the West as well. "KEMANE" belongs the wide family of lyre used in the area of The Black Sea , which had also been used in Kappadokia (tuning in fifths without sympathetica! strings).

We can also find it with six or seven strings, the so called "Viola d'Amore" or "Kenan" in the Byzantine era. The Renaissance viola has been mentioned in Byzantine scripts.

Lyra

The term lyra seems to correspond to the name given, during the Byzantine era, to the same instrument which is common today, in all its variations, throughout a vast area of the Mediterranean and the Balkans. The lyra is very similar to the lira made and played in Crete, except that in Crete, instrument-making has been influenced by that of the violin. The "primitive" lyra of Karpathos, and specifically that of Olympos, is made from a single block of wood, sculpted into a pear-shaped body. The slightly rounded body of lyra is prolonged by a neck ending on the top in a block which is also pear-shaped or spherical. In that, are set the pegs facing and extending forward.

Currently, numerous models tend to integrate, for decorative reasons, the shape of the scroll, the finger board and other morphology of some secondary characteristics of the violin. However, one can still see that the lyra played in Olymbos maintains the "primitive" lyra design, playing, and sound characteristics. This version preserves the proportions of the box and a type of bow-making which give it a sound quite distinct from that of the Cretan lyra. From the organologic point of view, it is in fact an instrument belonging to the family of bowed lutes (like the rebab from the Middle east), but the designation lyra may constitute a terminological survival relating to the performing method of an ancient Greek instrument. An interesting detail concerns the playing technique: The strings are never pressed from above with the flesh of the finger such as in the violin but touched by the nails laterally.

The lyra is played held in vertical position with the base set on the left knee. The short bow, whose horsetail hair is somewhat slack, is covered with small bells which provide an additional rhythmic interest, particularly if the instrument is played alone. And that is the reason why bells were installed on the bow. The laouto accompanying in Karpathos didn’t take place until the beginning of the century. Up to that time, lyra played alone or along with the tsambouna during the dancing portions of an event, therefore the lyra player provided some additional means of rhythm by adding those bells on the bow.

There are three strings which are tuned to the notes LA-RE-SOL (or A3-D3-G3), but the tuning is variable and generally higher. The central chord, serves mostly as a drone but not in all cases. The first is touched to produce the highest five notes, and the third is played empty, so as to complete the basic hexachord. Thus, along with the tsambouna(Gaida), it shares a certain conceptual analogy, but in its case, it is possible to distinguish between three modal scales which alternate in accordance with different blocks of melodic phases. It suffices to note that with the lyra, the "neutral" third of the tsambouna subdivides into two distinct thirds (minor and major), and that, if the first two scales can be used in a concomitant way with the tsambouna, the last, which allows for the augmentation of the fourth degree excludes this possibility.

The performance of the dance Sousta, which is more complex, also includes the inversion of roles between strings in the playing of the drone and melodic line, as well as the addition of a melodic seventh degree of the scale, thus making it impossible to perform on the tsambouna

Kabak kemane (gourd violin)

| Classification | *Bowed instruments

|

|---|---|

| Other names | gourd violin |

| Related instruments | *Gadulka

|

The kabak kemane(Iklığ, Rebab, Çepane, Gıcak, Yaylı kopuz, Cicak, Gıçek, Yık, Ik, İğil, Iyık ,Kıyak) is a bowed Turkish folk instrument. Shows variation according to regions and its form. It is known that instruments known as Kabak, Kemane, Igil, Rabab, Hegit at Hatay province, Rubaba in Southeastern Turkey, Kamancha in Azerbaijan and Gicak, Giccek or Gijek,Ghaychak among the central Asian Turks all come from the same origin.

Its body or the tekne part is generally made from vegetable marrow but wooden ones are also common. The sap is from hard woods. There is a thin wooden or metal rod underneath the body which is placed on the knee and enables the instrument to move to the left and right. The bow is made by tying horse hair on two ends of a stick. Previously strings made from gut called Kiriş were used which were replaced by metal ones at the present.

Kabak kemane is an instrument without pitches and produces all types of chromatic sounds easily. Its sound sis suitable for long plays and can be used for legato, Staccato and Pizzicato paces.

|

|

| Classification | *Bowed instruments

|

|---|---|

| Other names | Klasik kemençe |

| Related instruments | *Gadulka

|

side view

Classical Kemenche

The kemençe of Turkish classical music is a small instrument, from 40-41 cm in length, and 14-15 cm wide. Its body, reminiscent of half a pear, its elliptical pegbox (‘kafa’ or head), and its neck (‘boyun’) are carved and shaped from a single piece of wood. On its face are two large (4x3 cm) D-shaped soundholes, with the rounded sides facing out. The holes are approximately 25 mm apart. The bridge is placed between these holes, one side of it resting on the face of the instrument, and the other on the sound post. On the back side of the instrument there is a ‘back channel’ (‘sırt oluğu’). This channel begins from a triangular raised area (‘mihrap’) which is an extension of the neck and extends to the middle of the head, widens in the middle, and ends in a point near the tailpiece (“kuyruk takozu”). Each of the gut or metal strings, attached to the tailpiece, passes over the bridge and is wound onto its own peg. There is no nut to equalize the vibrating lengths of the strings. The three strings are tuned to yegâh (low re), rast (sol) and neva (high re) and the strings are stopped with the fingernails pressing laterally. All the strings are of gut, but the yegâh string is silver-wound. Today there are players who use synthetic racquet strings, aluminium-wound gut or synthetic silk strings, or chrome-wound steel violin strings. The pegs, which are from 14-15 cm long and rest on the chest during playing, form the points of a triangle on the head. Thus the middle string is 37-40 mm longer than the strings to either side of it. The vibrating lengths (that is, the portion between the bridge and the tuning pegs) of the short strings are from 25.5-26 cm. The sound post, which transmits the vibration of the strings to the back of the instrument -located under the neva string- is placed between the bridge and the back. A small hole 3-4 mm in diameter is bored in the back, directly below the bridge. Earlier, the head, neck and back channel were generally made of ivory, mother-of-pearl or tortoise shell inlay. Some kemençes made for the palace or mansions by great masters such as Büyük İzmitli or Baron, had backs, and even the edges of the sound holes, completely covered by mother-of-pearl, ivory or tortoiseshell inlay, or engraved and inlaid motifs.

Chuniri

Chuniri (Georgian: ჭუნირი) is an ancient Georgian string instrument played by a bow-shaped stick. It consists of oval body , neck and subsidiaries. The sound is reproduced with a bow. The body of the Svanetian Chuniri has the shape of a sieve. It is open from below. It is covered with leather . The neck is whole and flat that is attached into the body. On the head there are three holes for tuners. The subsidiaries are tuners , a bridge and a leg . On one end of the neck, horsehair strings are fastened. The bow has notches for strings. A Rachian Chianuri has a boat-like body, cut out of a whole piece of wood. It has 2 holes of 5-6 mm in diameter. The body is covered with leather that is fastened by a rope to the back part of the Chuniri. The neck is whole. Its round head has 2 holes for strainers. Khevsuretian and Tushetian Chianuris have round bodies. While playing, the musician touches the strings with finger-cushions but without touching the neck, therefore the Chianuri has a flageolet sound. The bow touches all strings simultaneously so the Chianuri has only three-part consonance. The bodies of Chianuris and Chuniris are made of fir or pine-tree. The necks are of birch or oak. The strings are made from horsehair. This sort of string gives the instrument very soft and sweet sounding. The Rachian Chianuri has 2 strings. Its tune is major third. The tune of the 3-stringed Svanetian and Tushetian Chuniri is second-third. Chuniri can have two or three strings made of horsehair. Its fiddlestick also has horsehair. Chianuri has the prop attached to the edge of the hollow body along the neck. Only the mountain inhabitants of Georgia preserved this instrument in its original form. This instrument is considered to be a national instrument of Svaneti and is thought to have spread in the other regions of Georgia from there. Chuniri has different names in different regions: in Khevsureti, Tusheti (Eastern mountainous parts) its name is Chuniri, and in Racha, Guria (western parts) “Chianuri”. Chuniri is used for accompaniment. It is often played in an ensemble with Changi and Salamuri. Both men and women played it. One-part songs, national heroical poems and dance melodies were performed on it in Svaneti. Chuniri and Changi are often played together in an ensemble when performing polyphonic songs. More than one Chianuri at a time is not used. Chianuri is kept in a warm place. Often, especially in rainy days it was warmed in the sun or near fireplace before using, in order to emit more harmonious sounds. This fact is acknowledged in all regions where the fiddlestick instruments were spread. That is done generally because dampness and wind make a certain affect on the instrument’s resonant body and the leather that covers it. In Svaneti and Racha people even could make a weather forecast according to the sound produced by Chianuri. Weak and unclear sounds were the signs of a rainy weather. The instrument’s side strings i.e. first and third strings are tuned in quart, but the middle (second) string is tuned in tercet with other strings. It was a tradition to play Chuniri late in the evening the day before a funeral. For instance, one of the relatives (man) of a dead person would sit down in open air by the bonfire and play a sad melody. In his song (sang in a low voice) he would remember the life of the dead person and the lives of the other dead ancestors of the family. Most of the songs performed on Chianuri are connected with sad occasions. There is an expression in Svaneti that “Chianuri is for sorrow”. However, it is often used at parties as well.

Abkharza

Abkharza is a two-string musical instrument which is played by a bow-shaped stick. It is thought to be widespread in all parts of Georgia from the region of Abkhazia. Mostly, Abkharza is used as an accompaniment instrument. There are performed one, two or three part songs, and national heroical poems on it. Abkharza is cut out of a whole wood piece and has a shape of a boat. Its overall length is 4800mm. its upper board is glued back to the main part. On the end it has two tuners.

Calabrian lyre

The Calabrian lyre is an ancient instrument of the family of string lutes. It’s a fiddle with a short neck, instrument typical of popular music. We can find similar instruments in many countries of southern Europe: Greece, Bulgary, Turkey, Dalmatia, Dodecanese and Crete. This instrument is obtained from one piece of solid wood, with pear-shaped back and three bowel chords. It’s a very common instrument in southern Italy traditions: in Calabria there are several different sizes and forms.

Koboz

It is an ancient Hungarian minstrel instrument of Central Asian origin. Minstrel song (énekmondás) is an inner process and there are persons in Hungary who still live and practice this form of music making. It is part of our Oriental musical inheritance. According to the widely traveled Kobzos Kiss Tamás, people of the Orient - Central Asians, Turks from Anatolia, peoples in the Caucasus, Japanese, Mongolians - consider Hungarians their relatives and a Folk of the East. The lyre (koboz) is a short necked, round bellied percussion instrument. It has 4-5 or more strings. In the remote past it was an instrument of soldiers. It is not known if the lyre, used by the Csángós, is the same as used in the 16th to 18th centuries. Szepcsi Csombor Márton writes, that according to French tradition, after the battle of Catalaunum, one-thousand lyre players accompanied the dead Huns to their graves. This made such an impression on the French, that in this single village they play the koboz since Atilla's time.

Kamanjah

The kamanjah (Arabic: كمنجة; pronounced kamangah in Egypt, and also known as jose) is an Arab violin made from half a coconut and covered with sheep hide or fish skin). This instrument is played holding it in the lap, sitting on the floor cross-legged. One to four strings pass down a long, un-fretted neck and over a small, spherical, wooden body covered with skin (sheep hide or fish skin). It is one of the predecessor's of the medieval lute, and is part of the spike family of instruments (so named for the spike that originates from the bottom of the sound-box and props on the floor.).

The term kamanjah may also be used to refer to the violin.

Vithele

The vithele was one of the most common bow instruments during the Middle Ages. It was played by nobles, peasants and jugglers alike, and was the favourite instrument of minstrels. Appearing at all festivities, it accompanied songs, dances and epic poems, alone or with a harp, psaltery, lute or recorder.The vithele was held on the shoulder in much the same way as a violin, although a number of paintings show musicians seated with the instrument on their knees. The vithele's shape, number of strings and bow can vary greatly. While the instrument's origins are hard to pinpoint, the bow appears to have been used in Spain and Italy in the tenth century, based on the practice in Arab and Byzantine countries.

Kamaicha

The kamaicha is of special interest as it connects the Indian subcontinent to western Asia and even Africa. As a matter of fact, it is the oldest bowed instrument in world literature, barring, perhaps, the Ravana hatta. As far as information is available, it was known in Egypt as well as in Sind from the tenth century A.D. The commonly accepted idea is that its name is derivable from the persian word "kaman"(meaning bow)+ "che" (Add to nouns to make diminutive nouns). It is of course a moot point whether the kamaicha went from Sind in the Indian subcontinent to West Asia and Egypt or vice versa; also was the ancient kamaicha similar in shape, size and mode of playing to our kamaicha. Answers to these queries might give us a better insight into the history of Indian bowed instruments. The kamaicha now found in our country is a bowed lute of Monghniar people of west Rajasthan which borders on the Sind province, now in Pakistan. The whole instrument is one piece of wood, the spherical bowl extended into a neck and fingerboard; the resonator is covered with leather and the upper portion with wood. There are four strings which are the main ones and there are a number of subsidiary ones passing over a thin bridge

Kyrympa

A musical instrument consisting of a thin metal tongue fixed at one end to the base of a two-pronged frame. The player holds the frame to his mouth, which forms a resonance cavity, and plucks the instrument's tongue.

Huuchir(Khuuchir)

Formerly, the nomads (called "the savages") mainly used the snake skin violin or horsetail violin. The Chinese call it "the Mongol instrument" or "Huk'in." It is tuned in the interval of a fifth and is small or middle sized.

The khuuchir has a small, cylindrical, square or cup-like resonator made of bamboo, wood or copper, covered with a snake skin and open at the bottom. The neck is inserted in the body of the instrument. It usually has four silk strings, of which the first and the third are accorded in unison, whereas the second and fourth are tuned in the upper fifth. The bow is coated with horsetail hair and inseparably interlaced with the string-pairs; in Chinese this is called "sihu," that is "four," also meaning, "having four ears." The smaller instruments have only two strings and are called "erh'hu," that is "two" in Chinese.

A two-string Spike fiddle. It is widespread in Gobi areas of central Mongolia and among Eastern Mongols, including Buryats. It is also played by Darhats in Hövsgöl aimag (province), north-west Mongolia, who call it hyalgasan huur, and by predominantly female ensemble-performers. The instrument is similar to Chinese fiddles, such as the huqin (hu means ‘barbarian’, suggesting that, from the Chinese perspective, the instrument came from foreign parts). The 12th-century Yüan-Shih describes a two-string fiddle, xiqin, bowed with a piece of bamboo between the strings, used by Mongols. During the Manchu dynasty, a similar two-string instrument bowed with a horsehair bow threaded between the strings was used in Mongolian music.

The huuchir has a cylindrical or polygonal open-backed body of wood or metal, through which is passed a wooden spike. Among herders, it is made from readily-available discarded items such as brick-tea containers, with a table of sheep- or goatskin. Traditional instruments made in Ulaanbaatar used snakeskin brought from China by migrant workers; modern urban and ensemble instruments also use snakeskin. A bridge, standing on the skin table, supports two gut or steel strings, which pass up the rounded, fretless neck to two posterior pegs and down to the bottom, where they are attached to the spike protruding from the body. A small metal ring, attached to a loop of string tied to the neck, pulls the strings towards it and can be adjusted to alter the pitch of the open strings, usually tuned to a 5th. The thick, bass string is situated to the left of the thin, high string in frontal aspect.

In performance, the musician rests the body of the instrument on the left upper thigh, close to the belly, with its table directed diagonally across the body and the neck leaning away from it. The thumb of the left hand rests upright along the neck of the instrument. Horsehairs of the arched, bamboo bow are divided into two sections so that one section passes over the bass string and the other over the top string. The bow is held underhand with a loose wrist. The index finger rests on the wood, and the bow hairs pass between middle and ring finger to both regulate the tension of the hairs and direct them. To sound the thick string, it is necessary to pull (tatah) one section of bow hairs with the ring finger, and to sound the thin string, to push the other section. Strings are touched lightly on top by the fingertips. In modern ensemble orchestras, there are small-, medium- and large-sized huuchir.

The Buryat Mongol huchir is a two- or four-string spike fiddle which is constructed with a cylindrical, hexagonal or octagonal resonator and mostly made of wood rather than metal. Buryats use silk or metal strings, tuned in 5ths; in the case of the four-string instrument, the first and third, and second and fourth strings are tuned in unison. The bow hair is threaded between the strings. On four-string types, the bow hair is divided into two strands, one fixed between the first and second strings, the other between the third and fourth. The huchir is related to the Nanai ducheke, the Nivkhi tïgrïk and the Mongolian huuchir.

Khuuchir and Dorvon Chikhtei Khuur

These two instruments are very similar. The Khuuchir and Dorvon Chikhtei Khuur being a two and four stringed spiked fiddle respectively. The resonator can be cylindrical or polygonal and made of either wood or metal. The face is covered with sheep or snakeskin with the belly or back left open to act as the sound hole. The strings are either gut or metal and are pulled towards the shaft (spike) by a loop of string and metal ring midway between the tuning pegs and the body. A horse-hair bow is threaded between the strings which are tuned a fifth apart. Chikhtei means ear in Mongolian so the name of the instrument translates as “four eared” instrument. One of the interesting things about these two instruments is the bowing technique. The bow rests between the two strings. To play the high string you bow in a forwards direction and to play the low string you bow in a backwards direction. On the Khuuchir this is relatively simple but on the Dorvon Chikhtei Khuur the bow is more complex. The two highest strings are not adjacent but alternate with the two low strings. The bow is split into two to enable bowing away from the body to play the two high strings and bowing towards the body to play the two low strings.

References

- Özhan Öztürk (2005). Karadeniz: Ansiklopedik Sözlük Black Sea Encyclopedic Dictionary. 2 Cilt (2 Volumes). Heyamola Yayıncılık. İstanbul. ISBN 975-6121-00-9

- Petrides, Th. "Traditional Pontic dances accompanied by the Pontic lyra

- Images taken from www.pontian.info "Pontian Music" (http://www.pontian.info/MUSIC/lyra.htm)

- The New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments: Londra, 1984.

- Asuman Onaran: Kemençe Seslerinin Armonik Analizi, İstanbul, 1959.

- M. Nazmi Özalp: Türk Sanat Mûsikîsi Sazlarından Kemençe, Ankara, tarihsiz (1985’ten önce).

- Laurence Picken: Folk Musical Instruments of Turkey, Londra, 1975.

- Rauf Yekta: Türk Musikisi (çev: Orhan Nasuhioğlu), İstanbul, 1986.

- Curt Sachs: The History of Musical Instruments, New York, 1940.

- Hedwig Usbeck: “Türklerde Musıki Aletleri”, Musıki Mecmuası, no. 235 - 243, 1968 - 1969.

See also

- Gadulka

- Gudok

- Gusle

- Rebab

- Kamancheh

- Kamanjah

- The lyra of Crete

- Turkish musical instruments

- Kobyz

- Adapazarı kemane

- Kars kemane

- Bafra kemane

- Yörük kemanesi

- Tırnak kemane

- Iklık

External links

- An article about Pontic kemenche from famous virtuoso Th. Petrides

- All About the Pontians

- www.kemence.com

- Kemenche video clips

- About kemenche

- Kabak Kemane

- Listen Kabak kemençe

- About Klassic kemençe (with illustrations)

- http://www.hangebi.ge/chunirien.htm

- http://www.hangebi.ge/afxarcaen.htm

- http://nuke.liuteriaetnica.it/

- http://www.passiondiscs.co.uk/articles/hungarian_folk_instruments2.htm#lyre

- http://muzmer.sdu.edu.tr/index.php?dosya=ykemanesi&tur=1

- http://muzmer.sdu.edu.tr/index.php?dosya=ykemanesi2&tur=1

- http://muzmer.sdu.edu.tr/index.php?dosya=iklik&tur=1

- http://muzmer.sdu.edu.tr/index.php?dosya=kemane&tur=1

- Shichepshin

- Shichepshin

- http://www.civilization.ca/arts/opus/opus211e.html

- http://khatylaev.sakhaopenworld.org/kyrympa.html

- Kemenche Components

- http://lh3.ggpht.com/_zZ1SbocnCdw/RyolBOzIGMI/AAAAAAAABhY/9-AWww04NNM/tkemence.jpg

Video

|

||||||||||||||