Karen people

| Karen | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A Karen girl wearing Thanaka | ||||||

| Total population | ||||||

|

7,400,000 |

||||||

| Regions with significant populations | ||||||

|

||||||

| Languages | ||||||

| Karen | ||||||

| Religion | ||||||

| Buddhism, Christianity, Animism |

The Karen (Burmese: ကရင်လူမျိုး; MLCTS: kayin lu myo:), self-titled Pwa Ka Nyaw Po or Kayan, and also known in Thailand as the Kariang (Thai: กะเหรี่ยง) or Yang, are an ethnic group in Burma and Thailand. The Karen make up approximately 7 percent of the total Burmese population of 47 million people.[1]

The Karen have fought for independence from Burma since 31 January 1949. Consequently, 31 January is recognized as Revolutionary Day amongst the Karen.

Contents |

Distribution

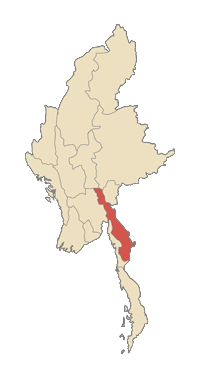

The Karen people live mostly in the hilly eastern border region of Burma,[2] primarily in Karen State, with some in Kayah State (Karenni State), southern Shan State (MoBye Region), Ayeyarwady Division (Irrawaddy Division), Southern Kawthoolei (Tenasserim Coastal Region) and in western Thailand. As with many widely-used ethnonyms — e.g., Miao — Karen was originally applied pejoratively by enemies. However, the term has since been claimed by the Karen themselves as a badge of pride.

The total number of Karen is difficult to estimate. The last reliable census of Burma was conducted in the 1930s. A 2006 VOA article cites an estimate of seven million in Burma. There are another 400,000[3] Karen in Thailand, where they are by far the largest of the hill tribes.

History

During World War II, when the Japanese occupied the region, long-term tensions between the Karen and Burma turned into open fighting. As a consequence, many villages were destroyed and massacres committed by both the Japanese and the Burma Independence Army (BIA) troops who helped the Japanese invade the country. Among the victims were a pre-war Cabinet minister, Saw Pe Tha, and his family. A government report later claimed the 'excesses of the BIA' and 'the loyalty of the Karens towards the British' as the reasons for these attacks. The intervention by Colonel Suzuki Keiji, the Japanese commander of the BIA, after meeting a Karen delegation led by Saw Tha Din, appeared to have prevented further atrocities.[4]

The Karen people aspired to have the areas where they were the majority formed into a subdivision or "state" within Burma similar to what the Shan, Kachin and Chin peoples had been given. A goodwill mission led by Saw Tha Din and Saw Ba U Gyi to London in August 1946 failed to receive any encouragement from the British government for any separatist demands. When a delegation of representatives of the Governor's Executive Council headed by Aung San was invited to London to negotiate for the Aung San-Atlee Treaty in January 1947, none of the ethnic minority members was included by the British government. The following month at the Panglong Conference, when an agreement was signed between Aung San as head of the interim Burmese government and the Shan, Kachin and Chin leaders, the Karen were present only as observers; the Mon and Arakanese were also absent. The British promised to consider the case of the Karen after the war. While the situation of the Karen was discussed, nothing practical was done before the British left Burma. The 1947 Constitution, drawn without Karen participation due to their boycott of the elections to the Constituent Assembly, also failed to address the Karen question specifically and clearly, leaving it to be discussed only after independence. The Shan and Karenni states were given the right to secession after 10 years, the Kachin their own state, and the Chin a special division. The Mon and Arakanese of Ministerial Burma were not given any consideration.[4]

In early February 1947, the Karen National Union (KNU) was formed at a Karen Congress attended by 700 delegates from the Karen National Associations, both Baptist and Buddhist (KNA - founded 1881), the Karen Central Organisation (KCO) and its youth wing, the Karen Youth Organisation (KYO), at Vinton Memorial Hall in Rangoon. The meeting called for a Karen state with a seaboard, an increased number of seats (25%) in the Constituent Assembly, a new ethnic census, and a continuance of Karen units in the armed forces. The deadline of March 3 passed without a reply from the British government, and Saw Ba U Gyi, the president of the KNU, resigned from the Governor's Executive Council the next day.[4]

After the war ended, Burma was granted independence in January 1948, and the Karen, led by the KNU, attempted to co-exist peacefully with the Burman ethnic majority. Karen people held leading positions in both the government and the army. In the fall of 1948, the Burmese government, led by U Nu, began raising and arming irregular political militias known as Sitwundan. These militias were under the command of Major Gen. Ne Win and outside the control of the regular army. In January 1949, some of these militias went on a rampage through Karen communities. In late January, the Army Chief of Staff, Gen. Smith Dun, a Karen, was removed from office and imprisoned. He was replaced by fanatic Burmese nationalist Ne Win.[4] These events happened at exactly the same time a commission looking into the Karen problem was due to make its report to the government. The events effectively killed the report. The Karen National Defence Organisation (KNDO), formed in July 1947, then rose up in an insurgency against the government.[4] They were helped by the defections of the Karen Rifles and the Union Military Police (UMP) units which had been successfully deployed in suppressing the earlier Burmese Communist rebellions, and came close to capturing Rangoon itself. The most notable was the Battle of Insein, nine miles from Rangoon, where they held out in a 112-day siege till late May 1949.[4]

Years later, the Karen had become the largest of 20 minority groups participating in an insurgency against the military dictatorship in Rangoon. During the 1980s, the KNU fighting force numbered approximately 20,000. After an uprising of the people of Burma in 1988, known as the 8888 Uprising, the KNU had accepted those demonstrators in their bases along the border. The dictatorship expanded the army and launched a series of major offensives against the KNU. By 2006, the KNU's strength had shrunk to less than 4,000, opposing what is now a 400,000-man Burmese army. However, the KNU continued efforts to resolve the conflict through political means.

The conflict continues as of 2006[update], with KNU headquarters in Mu Aye Pu, on the Burmese–Thai border. In 2004, the BBC, citing aid agencies, estimates that up to 200,000 Karen have been driven from their homes during decades of war, with 120,000 more refugees from Burma, mostly Karen, living in refugee camps on the Thai side of the border.

Many [1] [2], including some Karen [3] [4], accuse the military government of Burma of ethnic cleansing. The U.S. State Department has also cited the Burmese government for suppression of religious freedom [5]. This is a source of particular trouble to the Karen, as between thirty and forty percent of them are Christians [6][7] and thus, among the Burmese, a religious minority.

Language

The Karen languages are members of the Tibeto-Burman group of the Sino-Tibetan language family. The three main branches are Sgaw, Pwo, and Pa'o; they are not considered to be mutually intelligible (Lewis 1984). Karenni (also known Kayah or Red Karen) and Kayan (also known as Padaung) are related to the Sgaw branch. They are almost unique among the Tibeto-Burman languages in having a Subject Verb Object word order; other than Karen and Bai, Tibeto-Burman languages feature a Subject Object Verb order [8]. This is likely due to influence from neighboring Mon and Tai languages (Matisoff 1991).

Religion

The majority of Karen are Buddhist- animist influenced by the Mon who were dominant in Lower Burma until the middle of the 18th century. The first convert to Christianity in 1828 was baptised by Rev George Boardman, an associate of Adoniram Judson, founder of the American Baptist Foreign Mission Society. Persecution of Christians by the Burmese authorities has continued to this day fueled by the belief that Western imperialists have sought to divide the country not only on ethnic but on religious ground.[5]

Kawthoolei

Kawthoolei is the Karen name for the state that the Karen people of Burma have been trying to establish since the late 1940s. The precise meaning of the name is disputed even by the Karen themselves; possible interpretations include Flowerland and Land without evil, although, according to Martin Smith in Burma: Insurgency and the Politics of Ethnicity, it has a double meaning, and can also be rendered as the Land Burnt Black; hence the land that must be fought for. Kawthoolei roughly approximates to present-day Kayin State, although parts of the Burmese Ayeyarwady River delta with Karen populations have sometimes also been claimed. Kawthoolei as a name is a relatively recent invention, penned during the time of former Karen leader Ba U Gyi, who was assassinated around the time of Burma's independence from Britain.

See also

- Kayin state

- Karen-Ni

Footnotes

- ↑ Radnofsky, Louise (2008-02-14). "Burmese rebel leader shot dead", The Guardian. Retrieved on 2008-03-08.

- ↑ This area is generally referred to as the Karen hills in colonial literature, especially natural history texts such as Evans (1932).

- ↑ Delang, Claudio O. (Ed.) (2003). Living at the Edge of Thai Society: The Karen in the Highlands of Northern Thailand. London: Routledge.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Smith, Martin (1991). Burma - Insurgency and the Politics of Ethnicity. London and New Jersey: Zed Books. pp. 62-63,72-73,78-79,82-84,114-118,86,119.

- ↑ Keenan, Paul. "Faith at a Crossroads". Karen Heritage: Volume 1 - Issue 1, Beliefs.

References

- Evans, W.H. (1932). The Identification of Indian Butterflies (2nd ed). Mumbai, India: Bombay Natural History Society.

- Delang, Claudio O. (Ed.) (2003). Living at the Edge of Thai Society: The Karen in the Highlands of Northern Thailand. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-32331-2.

- Lewis, Paul; Elaine Lewis (1984). Peoples of the Golden Triangle. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd. ISBN 0-500-97472-1.

- Matisoff, James A. (1991). "Sino-Tibetan Linguistics: Present State and Future Prospects". Annual Review of Anthropology (Annual Reviews Inc.) 20: 469–504. doi:.

- Falla, Jonathan (1991). True Love and Bartholomew: Rebels of the Burmese Border. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-390192.

- Smith, Martin (1991). Burma - Insurgency and the Politics of Ethnicity. London and New Jersey: Zed Books. ISBN 0-86232-868-3/ISBN 0-86232-869-1 pbk.

Online

- "Burma:International Religious Freedom Report 2005". U.S. State Department (2005-11-08). Retrieved on 2006-07-18.

- "Karen Weblinks". Retrieved on 2006-07-18.

- Kendal, Elizabeth (2006-03-09). "Day of Prayer for Burma". Christian Monitor. Retrieved on 2006-07-18.

- "Description of the Sino-Tibetan Language Family". Retrieved on 2006-07-18.

Film

- The ongoing persecution of the Karen by the Burmese army is depicted in the 2008 film Rambo.

External links

- Karen Refugee Network, a non profit Australian organisation to resettle Karen Refugees in regional Australia

- Karenpeople.org, a non-profit web portal on the Karen peoples

- Karen.org, The website of the Karen National League of Bakersfield, California

- Karen Human Rights Group, a new website documenting the human rights situation of Karen villagers in rural Burma

- Drum Publication Group, web site of a community based Karen organization including an on-line English - Sgaw Karen Dictionary and Sgaw Karen and Burmese language e-books to download.

- The Karen Hilltribes Trust a UK charity helping the Thai Karen. They work in partnership with the local Karen on a number of projects such as installing clean water systems and teaching English in the schools.

- Kawthoolei meaning "a land without evil", is the Karen name of the land of Karen people. An independent and impartial media outlet aimed to provide contemporary information of all kinds — social, cultural, educational and political

- Burma's Karen Face Hard Times as Insurgency Begins Sixth Decade Voice of America, February 2006

- Burma's disorientated rebels BBC, November 2004

- Free Burma Rangers, website of NGO that provides humanitarian assistance to Internally Displaced People

- U.S. Dept. of State 2005 International Religious Freedom Report on Burma

- Index of IRF reports on Burma 2001-5

- Article about Karen, 2006

- Help without Frontiers

- The Quest for Karen Unity Ashley South, The Irrawaddy, October 2006

- Fifty Years of Struggle: A Review of the Fight for the Karen People's Autonomy (abridged) Ba Saw Khin, 1998 (revised 2005), Retrieved on 2006-11-09

- Revolution Reviewed: The Karens' Struggle for Right to Self-determination and Hope for the Future Saw Kapi, February 26 2006, Retrieved on 2006-11-12

- Kwekalu literally "Karen Traditional Horn", the only online Karen language news outlet based in Mergui/Tavoy District of Kawthoolei

- Karen Women's Organization

- Karen Mahouts Throw an Elephant Party The Irrawaddy, June 27, 2007

- YouTube coverage of Burma and Karen documentary filmmaker CNN, October 6, 2007

- Video of Karen The Globe and Mail

- Remembering our heroes and rethinking the revolutio Saw Kapi, Mizzima, August 13, 2008

|

|||||

|

|||||||||