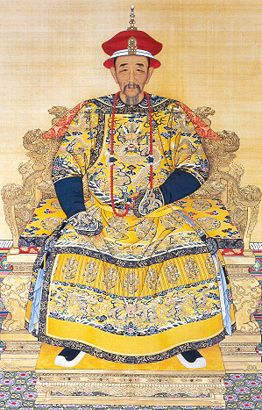

Kangxi Emperor

| Kangxi Emperor 康熙帝 |

|

|---|---|

| Qing Shengzu 清聖祖 |

|

|

|

| Reign | 17 February 1661 – 20 December 1722 |

| Predecessor | Shunzhi Emperor |

| Successor | Yongzheng Emperor |

| Spouse | Empress Xiao Cheng Ren Empress Xiao Zhao Ren Empress Xiao Yi Ren Empress Xiao Gong Ren |

| Issue | |

| Yinti, Beizi Yinreng, Prince Li Mi Yinzhi, Prince Cheng Yinzhen, Yongzheng Emperor Yinqi, Prince Heng Yinzuo Yinyou, Prince Chun Yinsi, Prince Lian Yintang, Beizi Yin'e, State Duke Yinzi Yintao, Prince Fu Yinxiang, Prince Yi Yinti, Prince Xun Yinyu, Prince Yu Yinlu, Prince Zhuang Yinli, Prince Guo Yinwei, Prince Yu Yinxi, Prince Shen Yinhu, Beile Yinqi, Beile Yinmi, Prince Jian |

|

| Full name | |

| Chinese: Aixin-Jueluo Xuanye 愛新覺羅玄燁 Manchu: Aisin-Gioro Hiowan Yei |

|

| Titles | |

| The Emperor | |

| Era name | |

| 1662 - 1723 - Kāngxī 康熙 | |

| Posthumous name | Emperor Hétiān Hóngyùn Wénwǔ Ruìzhé Gōngjiǎn Kuānyù Xiàojìng Chéngxìn Zhōnghé Gōngdé Dàchéng Rén 合天弘運文武睿哲恭儉寬裕孝敬誠信中和功德大成仁皇帝[Listen] |

| Temple name | Qing Shengzu 清聖祖 |

| Royal house | House of Aisin-Gioro |

| Father | Shunzhi Emperor |

| Mother | Empress Xiao Kang Zhang |

| Born | May 4, 1654 Beijing, China |

| Died | December 20, 1722 (aged 68) Beijing, China |

| Burial | Eastern Qing Tombs, Zunhua |

The Kangxi Emperor (Chinese: 康熙; pinyin: Kāngxī; Wade-Giles: K'ang-hsi; Mongolian Enkh Amgalan Khaan, May 4, 1654 – December 20, 1722) was the third Emperor of the Manchu Qing Dynasty[1][2] and the second Qing emperor to rule over China proper, from 1661 to 1722. His reign of 61 years makes him the longest-reigning Chinese Emperor in history and one of the longest in the world. However, having ascended the throne aged seven, he did not exercise much, if any, control over the empire until later, that role being fulfilled by his four guardians and his grandmother, the Grand Empress Dowager Xiaozhuang. Kangxi, considered one of China's greatest Emperors, was a pivotal figure in Chinese history, having defeated the Three Feudatories and the Zheng Jing government on Taiwan who previously would not submit to Qing rule, defeated Tzarist Russia, expanded the Qing empire in the northwest, and achieved such literary feats as the Kangxi Dictionary. Kangxi's reign brought about long-term stability and relative wealth after years of war and chaos.

Contents |

The Beginning of the Reign

Born on May 4, 1654 to the Shunzhi Emperor and Empress Xiaohui, the Kangxi Emperor, whose personal name is Aisin-Gioro Xuanye (Chinese: 愛新覺羅.玄燁), succeeded the imperial throne at the age of 8 on February 7, 1661, seven days after his father's death. Although the Kangxi reign period only started on February 18, 1662 (the first day of the following lunar year), the Kangxi Emperor actually ruled for more than 61 years from February 1661 to his death on December 20, 1722. His reign was the longest in Chinese history. His temple name (i.e. the official name given after his death for reveration in temple ceremonies) was Shengzu ("Sacred Ancestor"); his descendants thus called him Qing Shengzu.

His father died in his early twenties, and as Kangxi was not able to rule in his minority, the Shunzhi Emperor appointed Soni, Suksaha, Ebilun, and Oboi as the Four Regents. Soni died soon after his granddaughter was made the Empress, Heseli, leaving Suksaha at odds with Oboi politically. In a fierce power struggle, Oboi had Suksaha put to death, and seized absolute power as sole Regent. For a while Kangxi and the Court accepted this arrangement. In 1669 the Emperor arrested Oboi with help from the Xiao Zhuang Grand Dowager Empress and began to take control of the country himself.

In the spring of 1662, the regents ordered the Great Clearance in southern China, in order to fight the anti-Qing movement, begun by Ming Dynasty loyalists under the leadership of Zheng Chenggong (also known as Koxinga), to regain Beijing. This involved moving the entire population of the coastal regions of southern China inland.

He listed three issues of concern, being the flood control of the Yellow River, the repairing of the Grand Canal and the Revolt of the Three Feudatories in South China. The Revolt of the Three Feudatories broke out in 1673 and Burni of the Chahar Mongols also started a rebellion in 1675.

The Revolt of the Three Feudatories presented a major challenge. Wu Sangui's forces had overrun most of southern China and he tried to ally himself with local generals such as Wang Fuchen. Kangxi, however, united his court in support of the war effort and employed capable generals such as Zhou Pei Gong and Tu Hai to crush the rebellion. He also extended clemency to the common people who had been caught up in the fighting. Although Kangxi personally wanted to lead the battles against the 3 Feudatories, he was advised not to by his advisors. Kangxi would later lead the battle against the Mongol Dzungars.

Kangxi crushed the rebellious Mongols within two months and incorporated the Chahar into the Eight Banners. After the surrender of the Zheng family, the Qing Dynasty annexed Taiwan in 1684. Soon afterwards, the coastal regions were ordered to be repopulated, and to encourage settlers, the Qing government gave a financial incentive to each settling family.

In a diplomatic success, the Kangxi government helped mediate a truce in the long-running Trinh-Nguyen War in the year 1673. The war in Vietnam between these two powerful clans had been going on for 45 years without result. The peace treaty that was signed lasted for 101 years (Vietnam, Trials and Tribulations of a Nation by D. R. SarDesai, pg. 38, 1988).

Russia and the Mongols

At the same time, the Emperor was faced with the Russian advance from the north. The Qing Dynasty and the Russian Empire fought along the Sahaliyan ula (Amur, or Heilongjiang) Valley region in the 1650s, which ended with a Qing victory. The Russians invaded the northern frontier again in 1680s. After series of battles and negotiations, the two empires signed the Treaty of Nerchinsk in 1689 giving China the Amur valley and fixing a border.

At this time the Khalkha Mongols preserved their independence and only paid tribute to the Manchu Empire. A conflict between the Houses of Jasaghtu Khan and Tösheetü Khan led another dispute between the Khalkha and the Dzungar Mongols over influence over Tibetan Buddhism. In 1688 Galdan, the Dzungar chief, invaded and occupied the Khalkha homeland. The Khalkha royal families and the first Jebtsundamba Khutughtu crossed the Gobi Desert, sought help from the Qing Dynasty and, as a result, submitted to the Qing. In 1690, the Dzungar and the Manchu Empire clashed at the battle of Ulaan Butun in Inner Mongolia, during which the Qing army was severely mauled by Galdan.

In 1696, the Kangxi Emperor himself as commander in chief led three armies with a total of 80,000 in the campaign against the Dzungars. The notable second-in-command general behind Kangxi was Fei Yang Gu (費揚古) who was personally recommended by Zhou Pei Gong (周培公). The Western section of the Qing army crushed Galdan's army at the Battle of Zuunmod and Galdan died in the next year. The Dzungars continued to threaten China and invaded Tibet in 1717. They took Lhasa with an army 6,000 strong in response to the deposition of the Dalai Lama and his replacement with Lha-bzan Khan in 1706. They removed Lha-bzan from power and held the city for two years, destroying a Chinese army in 1718. Lhasa was not retaken until 1720.

The Banner System

The 8 Banner Army was already in decline. The 8 Banner Army was inferior to the Qing army at its peak during Huang Taji and early Shunzhi's reign; however, it was still superior to the later Yongzheng period and even more so than the Qianlong period. In addition, the Green Standard Army was still powerful with generals such as Tu Hai, Fei Yang Gu, Zhang Yong, Zhou Pei Gong, Shi Lang, Mu Zhan, Shun Shi Ke, Wang Jing Bao. These generals were stronger than the Qianlong period's generals.

The main reason for this decline was because of the change in system between Kangxi and Qianlong's reign. During Kangxi's reign, the empire still used the ancestor's military system that was far more efficient and strict. Based on the old system, if a general was to return by himself, he was to be slain. If a soldier returned by himself, the soldier was to be slain. Basically, a group of general and soldiers are to co-exist. This obviously meant that the generals and soldiers would fight for their lives because if the rest of the group were defeated, he would also die either way.

By Qianlong's reign, because the Lord status was passed on for generations, the war lords started to become lazy. The warlords' ancestor's had already given them fame and so the war lords saw the training of the army as less important than it once was. In a sense, Kangxi's reign was a reign where he tried to reunify China, which meant the war lords had to get back in combat, but by Qianlong's reign it was mostly expansion.

Treasury status

The contents of the national treasury in the Kangxi emperor's reign was:

- 1668 (7th year of Kangxi): 14,930,000 taels

- 1692: 27,385,631 taels

- 1702-1709: approximately 50,000,000 taels with little variation during this period

- 1710: 45,880,000 taels

- 1718: 44,319,033 taels

- 1720: 39,317,103 taels

- 1721 (60th year of Kangxi, second to last in his reign): 32,622,421 taels

As Kangxi was not yet of age when he became emporer he did not have control of the affairs of state until later on in his reign after the arrest of the regent Oboi in 1669.

The reasons for the great decline in the later years were that the wars has been taking great amounts of money from the treasury, that the border defense against the Dzungars and the later civil war in Tibet had been costly and that, due to Kangxi's old age, the emperor had no more energy left to handle corrupt officials.

To cure this treasury problem, Kangxi advised Prince Yong (the future Emperor Yongzheng) some tactics to make the economy more efficient. The other problem that concerned Kangxi when he died was the civil war in Tibet; both that problem and the treasury problem would be solved during Yongzheng's reign.

Cultural achievements

The Emperor, Kangxi ordered the compiling of the most complete dictionary of Chinese characters ever put together, The Kangxi Dictionary. In many ways this was an attempt to win over the Chinese gentry. Many scholars still refused to serve the dynasty and remained loyal to the Ming Dynasty. Kangxi persuaded scholars to work on the dictionary without asking them to formally serve the Qing. In effect they found themselves gradually taking on more and more responsibilities until they were normal officials.

Kangxi also was keen on Western technology and tried to bring it to China. This was helped through Jesuit missionaries such as Ferdinand Verbiest whom he summoned almost everyday to the Forbidden City. From 1711 to 1723 Matteo Ripa, an Italian priest born near Salerno, sent to China by Propaganda Fide, worked as a painter and copper-engraver at the Manchu court. In 1723 Matteo Ripa returned to Naples from China with four young Chinese Christians, in order to let them become priests and go back to China as missionaries; this was the fundation of the "Collegio dei Cinesi", sanctioned by Pope Clement XII to help the propagation of Christianity in China.

The "Chinese Institute" was the first Sinology School on the European continent and the nucleus of what would then become the Istituto Orientale and today's "Università degli studi di Napoli L'Orientale" (Naples Eastern University).

Kangxi was also the first Chinese Emperor to have played a western instrument, the piano. He also invented a Chinese calendar.

Twice Removing the Crown Prince

One of the mysteries of the Qing Dynasty was the event of Kangxi's will, which along with three other events, are known as the "Four greatest mysteries of the Qing Dynasty". To this day, whom Kangxi chose as his successor is still a topic of debate amongst historians, even though, supposedly, he chose Yinzhen, the 4th Prince, who was to become emperor Yongzheng. Many claimed that Yongzheng forged the will, and some suggest the will had chosen Yinti, the 14th Prince, who was apparently the favourite, as successor. However, there is strong evidence that Kangxi had in fact chosen Yinzhen as his successor.

Kangxi's first Empress gave birth to his second surviving son Yinreng, who was at age two named Crown Prince of the Great Qing Empire, which at the time, being a Han Chinese custom, ensured stability during a time of chaos in the south. Although Kangxi let several of his sons to be educated by others, he personally brought up Yinreng, intending to make him the perfect heir.

Yinreng was tutored by the mandarin Wang Shan, who was devoted to the prince, and who was to spend the latter years of his life trying to revive Yinreng's position at court. Through the long years of Kangxi's reign, however, factions and rivalries formed. Those who favored Yinreng, the 4th Imperial Prince Yinzhen, and the 13th Imperial Prince Yinxiang had managed to keep them in contention for the throne. Even though Kangxi favoured Yinreng and had always wanted the best for him, Yinreng did not prove co-operative.

He was said to have beaten and killed his subordinates, and was alleged to have had sexual relations with one of Kangxi's concubines, which was defined as incest and a capital offense, and purchased young children from the Jiangsu region for his pleasure. Furthermore, Yinreng's supporters, led by Songgotu, had gradually developed a "Crown Prince Party" (太子黨). The faction wished to elevate Yinreng to the Throne as soon as possible, even if it meant using unlawful methods.

Over the years the aging Emperor had kept constant watch over Yinreng, and he was made aware of many of his flaws. The relationship between father and son gradually worsened. Many thought that Yinreng would permanently damage the Qing Empire if he were to succeed the throne. But Kangxi himself also knew that a huge battle at court would ensue if he was to abolish the Crown Prince position entirely. Forty-six years into Kangxi's reign (1707), Kangxi decided that "after twenty years, he could take no more of Yinreng's actions, which he partly described in the Imperial Edict as "too embarrassing to be spoken of", and decided to demote Yinreng from his position as Crown Prince.

With Yinreng rid of and the position empty, discussion began regarding the choice of a new Crown Prince. Yinzhi (胤禔), Kangxi's eldest surviving son, the Da-a-go (大阿哥), was placed to watch Yinreng in his newly found house arrest, and assumed that because his father placed this trust in himself, he would soon be made heir.

The 1st Prince had many times attempted to sabotage Yinreng, even employing witchcraft. He went as far as asking Kangxi for permission to execute Yinreng, thus enraging Kangxi, which effectively erased all his chances in succession, as well as his current titles. In Court, the 8th Imperial Prince, Yinsi, seemed to have the most support among officials, as well as the Imperial Family.

In diplomatic language, Kangxi advised that the officials and nobles at court to stop the debates regarding the position of Crown Prince. But despite these attempts to quiet rumours and speculation as to who the new Crown Prince might be, the court's daily business was strongly disrupted. Furthermore, the first Prince's actions led Kangxi to think that it may have been external forces that caused Yinreng's disgrace. In the Third Month of the 48th Year of Kangxi's reign (1709), with the support of the fourth and thirteenth Imperial Princes, Kangxi re-established Yinreng as Crown Prince to avoid further debate, rumours and disruption at the imperial court. Kangxi had explained Yinreng's former wrongs as a result of mental illness, and he had had the time to recover, and think reasonably again.

In 1712, during Kangxi's last visit south to the Yangtze region, Yinreng and his faction yet again vied for supreme power. Yinreng ruled as regent during daily court business in Beijing. He had decided to allow an attempt at forcing Kangxi to abdicate when the Emperor returned to Beijing. Through several credible sources, Kangxi had received the news, and with power in hand, he saved the Empire from a coup d'etat. When Kangxi returned to Beijing in December 1712, he was enraged, and removed the Crown Prince once more. Yinreng was sent to court to be tried and placed under house arrest.

Kangxi had made it clear that he would not grant the position of Crown Prince to any of his sons for the remainder of his reign, and that he would place his Imperial Valedictory Will inside a box inside Qianqing Palace, only to be opened after his death. What was in his will is subject to intense historical debate.

Disputed succession

Following the abolition, Kangxi made some sweeping changes in the political landscape. The 13th Imperial Prince, Yinxiang, was placed under house arrest for "cooperating" with the former Crown Prince. Yinsi, too, was stripped of all imperial titles, only to have them restored years later. The 14th Imperial Prince Yinti, whom many considered to have the best chance in succession, was named "Border Pacification General-in-chief" quelling rebels and was away from Beijing when the political debates raged on. Yinsi, along with the 9th and 10th Princes, had all pledged their support for Yinti. Yinzhen was not widely believed to be a formidable competitor.

Official documents recorded that during the evening hours of December 20, 1722, Kangxi assembled at his bedside seven of the imperial princes who had not disgraced themselves—these were his third, fourth, eighth, ninth, tenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth sons. After his death, Longkodo announced that Kangxi had selected as his heir the fourth prince, Yinzhen. Yinti was in Xinjiang fighting a war when he received word that he had been summoned to Beijing. He did not arrive until days after Kangxi's death. In the meantime Yinzhen had declared that Kangxi had named him as heir. The dispute over his succession revolves around whether Kangxi intended his fourth or fourteenth son to succeed to the throne. (See: Yongzheng) He was entombed at the Eastern Tombs (東陵) in Zunhua County (遵化縣), Hebei.

See also

- Kangxi dictionary

- Oboi

- Ming Zhu

Family

- Father: Shunzhi Emperor of China (3rd son)

- Mother: Concubine from the Tongiya clan (1640–1663). Her family was of Jurchen origin but lived among Chinese for generations. It had Chinese family name Tong (佟) but switched to the Manchu clan name Tongiya. She was made the Ci He Dowager Empress (慈和皇太后) in 1661 when Kangxi became emperor. She is known posthumously as Empress Xiao Kang Zhang (Chinese: 孝康章皇后; Manchu: Hiyoošungga Nesuken Eldembuhe Hūwanghu).

Consorts

The total number is approximately 64.

- Empress Xiao Cheng Ren (died 1674) from the Heseri clan – married in 1665, Empress Xiaozhuang used this marriage to rule Oboi by Soni.

- Empress Xiao Zhao Ren (Manchu: Hiyoošungga Genggiyen Gosin Hūwanghu) from the Niuhuru clan.

- Empress Xiao Yi Ren (Manchu: Hiyoošungga Fujurangga Gosin Hūwanghu) from the Tunggiya clan, Yongzheng Emperor's foster-mother.

- Empress Xiao Gong Ren (Manchu: Hiyoošungga Gungnecuke Gosin Hūwanghu) from the Uya clan, Yongzheng Emperor's mother.

- Imperial Noble Consort Yi Hui (1668–1743) from the Tunggiya clan, Empress Xiao Yi Ren's younger sister.

- Imperial Noble Consort Dun Chi (1683–1768) from the Guargiya clan.

- Honored Imperial Noble Consort Jing Min (?–1699) from the Janggiya clan.

- Noble Consort Wen Xi (?–1695) from the Niuhuru clan, Empress Xiao Zhao Ren's younger sisTer.

- Consort Rong (?–1727) from the Magiya clan.

- Consort I (?–1733) from the Gorolo clan.

- Consort Hui (?–1732) from the Nala clan.

- Consort Shun Yi Mi (1668–1744) from the Wang clan was Han Chinese from origin.

- Consort Chun Yu Qin (?–1754) from the Chen clan.

- Consort Liang (?–1711) from the Wei clan.

- Consort Cheng (?-1740) from the Daigiya clan.

- Consort Xuan (?-1736) from the Borjigit clan was Mongol by origin.

- Consort Ding (1661-1757) from the Wanliuha clan.

- Consort Ping (?-1696) from the heseri clan, Empress Xiao Cheng Ren's younger sister.

- Consort Hui (different Chinese character from Consort 'Hui')(?-1670) from the Borjigit clan.

Sons

Having the longest reign in Chinese history, Kangxi also has the most children of all Qing Dynasty Emperors. He had officially 24 sons and 12 daughters. The actual number is higher, as most of his children died from illness.

| #1 | Record Name2 | 谱名 | Mother | Title | 爵位 | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chenghu | 承祜 | Imperial Consort Hui | died young | ||||

| Chengrui | 承瑞 | Empress Xiao Cheng Ren | 1669 - 1672 | died young | |||

| Chengqing | 承慶 | died young | |||||

| Sayinchamhg | 賽音察渾 | Imperial Consort Rong | died young | ||||

| Changhua | 長華 | Imperial Consort Rong | died young | ||||

| Changsheng | 長生 | Imperial Consort Rong | died young | ||||

| 1 | Yinshi | 胤禔 | Imperial Consort Hui | 1672 - 1734 | Beizi | Born Baoqing | |

| 2 | Yinreng | 胤礽 | Empress Xiao Cheng Ren | 1674 - 1725 | Crown Prince | 太子 | Crown Prince title abolished in 1708 and 1712 |

| Wanpu | 萬黼 | 1674 -1679 | died at 5 years old | ||||

| Yinzhan | 胤禶 | 1675 - | died young | ||||

| 3 | Yinzhi | 胤祉 | Imperial Consort Rong | 1677 - 1732 | Prince Cheng | 诚亲王 | peerage revoked by Yongzheng |

| 4 | Yinzhen | 胤禛 | Empress Xiao Gong Ren | 1678 - 1735 | Prince Yong | 雍亲王 | Emperor 1722 - 1735 |

| 5 | Yinqi | 胤祺 | Imperial Consrot Yi | 1679 - 1732 | Prince Heng | 恒亲王 | |

| 6 | Yinzuo | 胤祚 | Empress Xiao Gong Ren | 1680 - 1685 | Died young | ||

| 7 | Yinyou | 胤祐 | Imperial Consort Cheng | 1680 - 1730 | Prince Chun | 淳君王 | |

| 8 | Yinsi | 胤禩 | Imperial Consort Liang | 1681 - 1726 | Prince Lian | 廉亲王 | Title abolished, expelled from clan, Renamed Akina |

| 9 | Yintang | 胤禟 | Imperial Consort Yi | 1683 - 1726 | Beizi | 贝子 | Titles removed, expelled from clan, Renamed Saisihe |

| 10 | Yin'e | 胤俄 | Noble Consort Wen-Xi | 1683 - 1731 | State Duke | 辅国公 | Titles removed |

| 11 | Yinzi | 胤禌 | Imperial Consort Yi | 1684 | Died young | ||

| 12 | Yintao | 胤祹 | Imperial Consort Ding | 1685 - 1764 | Prince Fu | 履亲王 | Given peerage by nephew Qianlong Emperor |

| 13 | Yinxiang | 胤祥 | Imperial Noble Consort Jing-Min | 1686 - 1730 | Prince Yi | 怡亲王 | Peerage title inherited |

| 14 | Yinti | 胤禵 | Empress Xiao Gong Ren | 1688 - 1756 | Prince Xun | 恂郡王 | Peerage title abolished, rumored to be Kangxi's actual successor Born Yinzheng (胤祯), to avoid the nominal taboo of the Emperor, change into Yunti(允禵) |

| 15 | Yinyu | 胤禑 | Imperial Consort Shu-Mi-Yi | 1693 - 1731 | Prince Yu | 愉郡王 | |

| 16 | Yinlu | 胤祿 | Imperial Consort Shu-Mi-Yi | 1695 - 1768 | Prince Zhuang | 莊亲王 | Adopted by another branch of clan |

| 17 | Yinli | 胤礼 | Imperial Consort Jin | 1697 - 1738 | Prince Guo | 果亲王 | |

| 18 | Yinxie | 胤祄 | Imperial Consort Shu-Mi-Yi | 1701 - 1708 | Died young | ||

| 19 | Yinji | 胤禝 | Imperial Concubine Xiang | 1706 - 1708 | Died young | ||

| 20 | Yinwei | 胤禕 | Imperial Concubine Xiang | 1693 - 1731 | Prince Yu | 愉郡王 | |

| 21 | Yinxi | 胤禧 | Imperial Concubine Xiang | 1711 - 1758 | Prince Shen | 慎郡王 | |

| 22 | Yinhu | 胤祜 | Imperial Concubine Jin | 1711 - 1731 | Beile | 贝勒 | |

| 23 | Yinqi | 胤祁 | Imperial Concubine Jing | 1713 - 1731 | Beile | 贝勒 | |

| 24 | Yinmi | 胤祕 | Imperial Concubine Mu | 1716 - 1773 | Prince Jian | 缄亲王 |

- Notes: (1) The order by which the Princes were referred to, and recorded on official documents were all dictated by the number they were assigned by the order of birth. This order was unofficial until 1677, when Kangxi decreed that all of his male descendants must adhere to a generation code as their middle character (see Chinese name). As a result of the new system, the former order was abolished, with Yinzhi becoming the first Prince, thus the current numerical order. (2) All of Kangxi's sons changed their names upon Yongzheng's accession in 1722 by modifying the first character from "胤" (yin) to "允" (yun) to avoid the nominal taboo of the Emperor. Yinxiang was posthumously allowed to change his name back to "Yinxiang".

Daughters

- Seventh daughter: Princess (1682 - 1682), daughter of Empress Xiao Yi Ren

- Eighth daughter: Princess Wen Xian (固倫溫憲公主) (1683 - 1702).

- Twelfth daughter: (1686 - 1697).

The Kangxi Emperor in fiction

- The Kangxi Emperor was featured in Louis Cha's famous Wuxia novel The Deer and the Cauldron. He had a close relationship with the protaganist Wei Xiaobao, who helped him strengthen his rule over the empire.

- A 2001 novel entitled The Great Kangxi Emperor (康熙王朝) written by novelist Er Yuehe featured a romanticised version of the emperor's biography

In films, television and popular culture

- A Mainland China CCTV 46 episodes drama series entitled The Kangxi Dynasty (康熙王朝) based on the novel of the same title by Er Yuehe was produced in 2001, starring Chen Daoming as the Kangxi Emperor.

- Kangxi was also featured as the leader of the chinese people in the real-time strategy game Age of Empires 3: the Asian Dynasties

Notes

- ↑ Schirokauer, Conrad. A Brief History of Chinese Civilization( Thompson Wadswoth, 2006), p. 234-235.

- ↑ He can be viewed as either the third or the fourth emperor of the dynasty, depending on whether the dynasty's founder, Nurhaci, who used the title of Khan but was posthumously given imperial title, is to be treated as an emperor or not

External links

Sources

- Spence, Jonathan. Emperor of China: Self-Portrait of K'ang-hsi. Jonathan Cape (1974) ISBN 0224009400.

|

Kangxi Emperor

House of Aisin-Gioro

Born: May 4 1654 Died: December 20 1722 |

||

| Preceded by The Shunzhi Emperor |

Emperor of China 1661–1722 |

Succeeded by The Yongzheng Emperor |