Kalmar Union

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History of Scandinavia |

|---|

|

The Kalmar Union (Danish, Norwegian and Swedish: Kalmarunionen) is a historiographical term meaning a series of personal unions (1397–1523) that united the three kingdoms of Denmark, Norway (with Iceland, Greenland, Faroe Islands, Shetland and Orkney) and Sweden (including some of Finland) under a single monarch, though intermittently.[1]

The countries had not technically given up their sovereignty, nor their independence, but in practical terms, they were only autonomous, the common monarch holding the sovereignty and, particularly, leading foreign policy; diverging interests (especially the Swedish nobility's dissatisfaction over the dominant role played by Denmark and Holstein) gave rise to a conflict that would hamper the union in several intervals from the 1430s until the union's breakup in 1523 when Gustav Vasa became king of Sweden. The union was never formally dissolved - some argue that its conception actually was never ratified either. Norway and her overseas dependencies, however, continued to remain a part of the realm of Denmark-Norway under the Oldenburg dynasty for several centuries after the dissolution.

Contents |

Union

The union was the work of Queen Margaret of Denmark (1353–1412), a daughter of King Valdemar IV of Denmark. At the age of ten, she was married to King Haakon VI of Norway and Sweden, who was the son of King Magnus II of Sweden and Norway. Margaret succeeded in having her son Olav recognized as heir to the throne of Denmark. In 1376 Olav inherited the crown of Denmark from his maternal grandfather as King Oluf III, with his mother as guardian. When Haakon VI died in 1380, Olav also inherited the crown of Norway. The two kingdoms were united in a personal union under a child king, with the king's mother as his guardian. Olav also had designs on the throne of Sweden (in opposition to Albert of Mecklenburg) from 1385 until 1387.

Before Olav came of age and could take over the government, he died in 1387. Margaret made the Danish Council of the Realm elect her as regent of Denmark, but she did not attempt to assume the title of queen. The next year she was also recognized as regent of Norway, on February 2 1388. She adopted her sister's grandson Bogislav, a son of prince Vartislav of Pomerania, and gave him the more Nordic name Erik. She manoeuvred to have the Norwegian Council recognize him as heir to the throne of Norway,[2] in spite of his not being first in the line of succession, and he was installed as king of Norway in 1389, still with Margaret as his guardian.

In Sweden, this was a time of conflict between king Albert of Mecklenburg and leaders of the nobility. Albrecht's enemies in 1388 elected Margaret as regent in the parts of Sweden that they controlled, and promised to assist her in conquering the rest of the country. Their common enemy was the Hanseatic League and the growing German influence over the Scandinavian economy.[3] After Danish and Swedish troops in 1389 defeated the Swedish king, Albert of Mecklenburg, and he subsequently failed to pay the required tribute of 60,000 silver marks within three years after his release,[4] her position in Sweden was secured. The three Nordic kingdoms were united under a common regent. Margaret promised to protect the political influence and privileges of the nobility under the union. Her grandnephew Erik, already king of Norway since 1389, succeeded to the thrones of Denmark and Sweden in 1396.

The Nordic union was in a way formalized on June 17 1397 by the Treaty of Kalmar, signed in the Swedish castle of Kalmar, on Sweden's south-east coast, in medieval times close to the Danish border. The treaty stipulated an eternal union of the three realms under one king, who was to be chosen among the sons of the deceased king. They were to be governed separately, together with the respective councils, and according to their ancient laws, but foreign policy was to be conducted by the king. It has been doubted that several of the signatories were personally present (for example, the entire Norwegian "delegation"), and it has been argued that the Treaty was only a draft document. It seems to be an ascertained fact that the treaty was never ratified by "constitutional" bodies of the three kingdoms.

The short-term effects of the Treaty were achieved anyway, independently of whether the Treaty was binding or not, because the stipulations as to day-to-day governmental operations were mostly matters which were in the power of the king to decide. And, until Eric was deposed in the late 1430s, he made decisions as to each of the kingdoms in accordance with the treaty intentions. Long-term stipulations, such as what should happen when the individual monarch ceases to reign and a new monarch succeeds, were not among those achieved without problems, as subsequent events show during next 130 years. At each junction, installation of a new monarch tended to mean a break-up of the union for a while. For the moment, Eric of Pomerania became unanimously the monarch of all three kingdoms. At Kalmar, the 15-year-old Eric of Pomerania was crowned king of all three kingdoms by the archbishops of Denmark and Sweden, but Margaret managed to remain in control until her death in 1412.

It is said that contemporaries of the Union would not recognize the historiographical term, "Union of Kalmar" - that they just understood that much of the time, the three kingdoms shared a common king. While the term meaning "Treaty of Kalmar", the pact, was known already at the time, the term "Union of Kalmar" cannot be found in any contemporary documents. Presumably, the term union was coined for this only by historians writing centuries later.

Conflict

The Swedes were not happy with the Danes' frequent wars on Schleswig, Holstein, Mecklenburg, and Pomerania, which were a disturbance to Swedish exports (notably iron) to the European continent. Furthermore, the centralization of government in Denmark raised suspicions. The Swedish Privy Council wanted to retain a fair degree of self-government. The unity of the union eroded in the 1430s, even to the point of armed rebellion (the Engelbrecht rebellion), leading to the expulsion of Danish forces from Sweden. Erik was deposed (1438–39) as the union king and was succeeded by the childless Christopher of Bavaria. In the power vacuum that arose following Christopher's death (1448), Sweden elected Charles VIII king with the intent to reestablish the union under a Swedish crown. Charles was elected king of Norway in the following year, but the counts of Holstein were more influential than the Swedes and the Norwegians together, and made the Danish Privy Council appoint Christian I of Oldenburg as king. During the next seven decades struggle for power and the wars between Sweden and Denmark would dominate the union.

After the temporarily successful reconquest of Sweden by Christian II and the subsequent Stockholm bloodbath in 1520, the Swedes started yet another rebellion which ousted the Danish forces once again in 1521. While independence had been reclaimed, the election of King Gustav of the Vasa on June 6 1523, restored forever the independence and also practical sovereignty for Sweden and dissolved the informal union. The day of Gustav Vasa's coronation is since 1983 the National Day of Sweden, but was only recently made a national holiday, in 2005 (482 years later).

Final dissolution

One of last structures of the Kalmar Union, or, rather, medieval separateness, remained until 1536 when the Danish Privy Council, in the aftermath of a civil war, unilaterally declared Norway to be a Danish province [6], without consulting their Norwegian colleagues. This had a practical effect, despite the fact that the Norwegian council never recognized the declaration formally. Norway kept some separate institutions and its legal system.[6] However, the Norwegian possessions of Iceland, Greenland, and the Faroe Islands came under direct control of the crown, in principle the Norwegian crown, which under the Danish union (the monarch lived in Denmark) meant that they were controlled from Denmark and not from Norway. In the 1814 treaty of Kiel, the king of Denmark-Norway was forced to cede mainland Norway to the king of Sweden, Charles XIII. Norway, led by the viceroy, prince Christian Frederik, objected to the terms of the treaty. A constitutional assembly declared Norwegian independence, adopted a liberal constitution, and elected Christian Frederik king. After a brief war with Sweden, however, the peace terms of the Convention of Moss recognized Norwegian independence, but forced Norway to accept a personal union with Sweden.

In the middle of the 19th century, many intellectuals joined the Scandinavist movement, which promoted closer contacts between the three countries. At the time, the union between Sweden and Norway under one monarch, together with the fact that King Frederik VII of Denmark had no male heir, gave rise to the idea of reuniting the countries of the Kalmar Union, except Finland.

See also

- List of Kalmar Union monarchs

- Grand Duchy of Finland

- Scandinavian royal lineage chart for the time around the founding of the Kalmar Union

- Denmark-Norway

- Union between Sweden and Norway

Notes

- ↑ Boraas, Tracey (2002). Sweden. Capstone Press. pp. p24. ISBN 0-7368-0939-2.

- ↑ Boraas, Tracey; Henry Smith Williams (1904). The Historians' History of the World. The Outlook Company. pp. p204.

- ↑ Nordstrom, Byron (2000). Scandinavia since 1500. University of Minnesota Press. pp. p22. ISBN 0-8166-2098-9.

- ↑ Boraas, Tracey; Henry Smith Williams (1904). The Historians' History of the World. The Outlook Company. pp. p205.

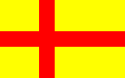

- ↑ depicting: (Centre): a lion rampant crowned maintaining an axe (representing the Hereditary Kingdom of Norway) within an inescutcheon upon a cross over all; Quarterly: in Dexter Chief, three lions passant in pale crowned and maintaining a Danebrog upon a semy of hearts (representing Denmark); in Sinister Chief: three crowns (representing Sweden or the Kalmar Union); in Dexter Base: a lion rampant (Folkung lion) (representing Sweden); and in Sinister Base: a griffin segreant to sinister (representing Pomerania).

External links

- Kalmar Union Flag - Flags of the World

- The Kalmar Union - Maps of the Kalmar Union

- Alternative history scenario in which the Kalmar Union survived