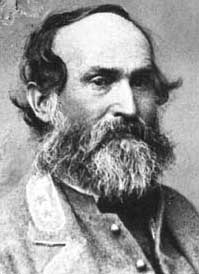

Jubal Anderson Early

| Jubal Anderson Early | |

|---|---|

| November 3, 1816 – March 2, 1894 (aged 77) | |

|

|

| Nickname | Old Jube, Old Jubilee |

| Place of birth | Franklin County, Virginia |

| Place of death | Lynchburg, Virginia |

| Allegiance | United States of America Confederate States of America |

| Service/branch | United States Army Confederate Army |

| Years of service | 1837–38, 1846–48 (U.S.), 1861–65 (C.S.A) |

| Rank | Lieutenant General |

| Battles/wars | Seminole Wars Mexican-American War American Civil War

|

| Other work | Lawyer |

Jubal Anderson Early (November 3, 1816 – March 2, 1894) was a lawyer and Confederate general in the American Civil War. The articles written by him for the Southern Historical Society in the 1870s established the Lost Cause point of view as a long-lasting literary and cultural phenomenon.[1]

Contents |

Early years

Early was born in Franklin County, Virginia, third of ten children of Ruth Hairston and Joab Early.[2] He graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1837, ranked 18th of 50. During his tenure at the Academy he was engaged in a dispute with a fellow cadet named Lewis Addison Armistead. Armistead broke a mess plate over Early's head, an incident which prompted Armistead's dismissal from the Academy. After graduating from the Academy, Early fought against the Seminole in Florida as a second lieutenant in the 3rd U.S. Artillery regiment before resigning from the army for the first time in 1838. He practiced law in the 1840s as a prosecutor for both Franklin and Floyd Counties in Virginia. He was noted for a case in Mississippi, where he beat the top lawyers in the state. His law practice was interrupted by the Mexican-American War from 1846–1848. He served in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1841–1843.

Civil War

Early was a Whig and strongly opposed secession at the April 1861 Virginia convention for that purpose. However, he was soon angrily aroused by the aggressive movements of the Federal government (President Abraham Lincoln's call for 75,000 volunteers to suppress the rebellion) and accepted a commission as a brigadier general in the Virginia Militia. He was sent to Lynchburg, Virginia, to raise three regiments and then commanded one of them, the 24th Virginia Infantry, as a colonel in the Confederate States Army.

Early was promoted to brigadier general after the First Battle of Bull Run (or First Manassas) in July 1861. In that battle, he displayed valor at Blackburn's Ford and impressed General P.G.T. Beauregard. He fought in most of the major battles in the Eastern Theater, including the Seven Days Battles, Second Bull Run, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, and numerous battles in the Shenandoah Valley. During the Gettysburg Campaign, Early's Division occupied York, Pennsylvania, the largest Northern town to fall to the Rebels during the war.

Early was trusted and supported by the commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, Robert E. Lee. Lee affectionately referred to Early as his "Bad Old Man" because of his irascible demeanor and short temper, but appreciated Early's aggressive fighting and ability to command units independently. Most of Early's soldiers referred to him as "Old Jube" or "Old Jubilee" with enthusiasm and affection. His subordinate generals often felt little of this affection. Early was an inveterate fault-finder and offered biting criticism of his subordinates at the least opportunity; in the reverse case, he was generally blind to his own mistakes and reacted fiercely to criticism or suggestions from below.

Early was wounded at Williamsburg in 1862, while leading a charge against staggering odds.

Serving under Stonewall Jackson

He convalesced in Rocky Mount, Virginia, and returned in two months, under the command of Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson, in time for Malvern Hill. There, Early demonstrated his career-long lack of aptitude for battlefield navigation and his brigade was lost in the woods; it suffered 33 casualties without any significant action. In the Northern Virginia Campaign, Early was noted for his performance at the Battle of Cedar Mountain and arrived in the nick of time to reinforce A.P. Hill on Jackson's left on Stony Ridge in the Second Battle of Bull Run.

At Antietam, Early ascended to division command when his commander, Alexander Lawton, was wounded. Lee was impressed with his performance and retained him at that level. At Fredericksburg, Early saved the day by counterattacking the division of George G. Meade, which penetrated a gap in Jackson's lines. He was promoted to major general on January 17, 1863. At Chancellorsville, Lee gave him a force of 5,000 men to defend Fredericksburg at Marye's Heights against superior forces (two corps) under Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick. Early was able to delay the Union forces and pin down Sedgwick while Lee and Jackson attacked the remainder of the Union troops to the west. Sedgwick's eventual attack on Early up Marye's Heights is sometimes known as the Second Battle of Fredericksburg.

Gettysburg and the Overland Campaign

During the Gettysburg Campaign, Early commanded a division in the corps of Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell. His troops were instrumental in defeating Union defenders at Winchester, capturing a number of prisoners, and opening up the Shenandoah Valley for Lee's oncoming forces. Early's division, augmented with cavalry, eventually marched eastward across the South Mountain range in Pennsylvania, seizing vital supplies and horses along the way. He captured Gettysburg on June 26 and demanded a ransom, which was never paid. Two days later, he entered York County and seized York, the largest Northern town to fall to the Confederates during the war. Here, his ransom demands were partially met, including a payment of $28,000 in cash. Elements of Early's command on June 28 reached the Susquehanna River, the farthest east in Pennsylvania that any organized Confederate force would penetrate. On June 30, Early was recalled as Lee concentrated his army to meet the oncoming Federals.

Approaching Gettysburg from the northeast on July 1, 1863, Early's division was on the leftmost flank of the Confederate line. He soundly defeated Francis Barlow's division (part of the Union XI Corps), inflicting three times the casualties to the defenders as he suffered, and drove the Union troops back through the streets of town, capturing many of them. In the second day at Gettysburg, he assaulted East Cemetery Hill as part of Ewell's efforts on the Union right flank. Despite initial success, Union reinforcements arrived to repulse Early's two brigades. On the third day, Early detached one brigade to assist Edward "Allegheny" Johnson's division in an unsuccessful assault on Culp's Hill. Elements of Early's division covered the rear of Lee's army during its withdrawal from Gettysburg on July 4 and July 5.

Early served in the Shenandoah Valley over the winter of 1863–64. During this period, he occasionally filled in as corps commander during Ewell's absences for illness. On May 31, 1864, Lee expressed his confidence in Early's initiative and abilities at higher command levels, promoting him to the temporary rank of lieutenant general.

Upon his return from the Valley, Early fought in the Battle of the Wilderness and assumed command of the ailing A.P. Hill's Third Corps during the march to intercept Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant at Spotsylvania Court House. At Spotsylvania, Early occupied the relatively quiet right flank of the Mule Shoe. At the Battle of Cold Harbor, Lee replaced the ineffectual Ewell with Early as commander of the Second Corps.

The Valley, 1864

Early's most important service was that summer and fall, in the Valley Campaigns of 1864, when he commanded the Confederacy's last invasion of the North. As Confederate territory was rapidly being captured by the Union armies of Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman, Lee sent Early's corps to sweep Union forces from the Shenandoah Valley and to menace Washington, D.C., hoping to compel Grant to dilute his forces against Lee around Richmond and Petersburg, Virginia. Early delayed his march for several days in a futile attempt to capture a small force at Maryland Heights and to rest his men from July 4 through July 6.[3] Although elements of his army would eventually reach the outskirts of Washington at a time when it was largely undefended, the time delay at Maryland Heights would ultimately prove detrimental for his ability to engage in any attack on the city itself.

During the time of Early's Maryland Heights campaign, Grant sent two VI Corps divisions from the Army of the Potomac to reinforce Union Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace. With 5,800 men, he delayed Early for an entire day at the Battle of Monocacy, allowing more Union troops to arrive in Washington and strengthen its defenses. This invasion caused considerable panic in Washington and Baltimore, and Early was able to get to the outskirts of Washington. He sent some cavalry under Brig. Gen. John McCausland to the west side of Washington. Knowing that he did not have sufficient strength to capture the city, Early demonstrated outside Fort Stevens and Fort DeRussy, and there was skirmishing and artillery duels on July 11 and July 12. Abraham Lincoln watched the fighting on both days from the parapet at Fort Stevens, becoming the only sitting U.S. President to come under hostile military fire. After Early withdrew, he said to one of his officers, "Major, we haven't taken Washington, but we scared Abe Lincoln like hell."

Early crossed the Potomac into Leesburg, Virginia, on July 13 and then withdrew to the Valley. He defeated the Union army under George H. Crook at Kernstown on July 24, 1864. Six days later, he ordered his cavalry to burn the city of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, in retaliation for Maj. Gen. David Hunter's burning of the homes of several prominent Southern sympathizers in Jefferson County, West Virginia, earlier that month. Through early August, Early's cavalry and guerrilla forces attacked the B&O Railroad in various places.

Grant, losing patience and realizing Early could attack Washington any time he pleased, dealt with the threat by sending out an army under Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan. At times outnumbering the Confederates three to one, Sheridan defeated Early in three battles starting in early August and laid waste to much of the agricultural properties in the Valley, denying their use as supplies for Lee's army. In a brilliant surprise attack, Early routed two thirds of the Union army at the Battle of Cedar Creek on October 19, 1864, but his troops were hungry and exhausted and fell out of their ranks to pillage the Union camp; Sheridan managed to rally his troops and defeat Early decisively.

Most of the men of Early's corps rejoined Lee at Petersburg in December, while Early remained to command a skeleton force. His force was nearly destroyed at Waynesboro and Early barely escaped capture with a few members of his staff. Lee relieved Early of his command in March 1865, because he doubted Early's ability to inspire confidence in the men he would have to recruit to continue operations. He wrote to Early of the difficulty of this decision:

While my own confidence in your ability, zeal, and devotion to the cause is unimpaired, I have nevertheless felt that I could not oppose what seems to be the current of opinion, without injustice to your reputation and injury to the service. I therefore felt constrained to endeavor to find a commander who would be more likely to develop the strength and resources of the country, and inspire the soldiers with confidence. ... [Thank you] for the fidelity and energy with which you have always supported my efforts, and for the courage and devotion you have ever manifested in the service ...

– Robert E. Lee, letter to Early

After the War

Early fled when the Army of Northern Virginia surrendered on April 9, 1865. He rode horseback to Texas, hoping to find a Confederate force still holding out, then proceeded to Mexico, and from there, sailed to Cuba and Canada. Living in Toronto, he wrote his memoirs, A Memoir of the Last Year of the War for Independence, in the Confederate States of America, which focused on his Valley Campaign. They were published in 1867.

He returned to Virginia in 1869, resuming the practice of law. He was pardoned in 1868 by President Andrew Johnson, but still remained an unreconstructed rebel. He was among the most vocal of those who promoted a bitter Lost Cause movement and who vilified the actions of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet at Gettysburg. He was involved with the Louisiana Lottery along with retired General P.G.T. Beauregard.

At the age of 77, after falling down a flight of stairs, Early died in Lynchburg, Virginia. He is buried in Spring Hill Cemetery.

Legacy

Early's original inspiration for his views on the Lost Cause may have come from General Robert E. Lee himself. When he published his farewell order to the Army of Northern Virginia, Lee spoke of the "overwhelming resources and numbers" that the Confederate army fought against. In a letter to Early, Lee requested information about enemy strengths from May 1864 to April 1865, the period in which his army was engaged against Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant (the Overland Campaign and the Siege of Petersburg). Lee wrote, "My only object is to transmit, if possible, the truth to posterity, and do justice to our brave Soldiers."[4] In another letter, Lee wanted all "statistics as regards numbers, destruction of private property by the Federal troops, &c." because he intended to demonstrate the discrepancy in strength between the two armies and believed it would "be difficult to get the world to understand the odds against which we fought." Referring to newspaper accounts that accused him of culpability in the loss, he wrote, "I have not thought proper to notice, or even to correct misrepresentations of my words & acts. We shall have to be patient, & suffer for awhile at least. ... At present the public mind is not prepared to receive the truth."[4] All of these were themes that Early and the Lost Cause writers would echo for decades.

Lost Cause themes were taken up by memorial associations such as the United Confederate Veterans and the United Daughters of the Confederacy, helping in some degree the Southerners to cope with the dramatic social, political, and economic changes in the postbellum era, including Reconstruction.[5]

Early's contributions to the Confederacy's last efforts at survival were very significant. Some historians contend that he extended the war six to nine months because of his efforts at Washington and in the Valley. The following quote summarizes an opinion held by his admirers:

Honest and outspoken, honorable and uncompromising, Jubal A. Early epitomized much that was the Southern Confederacy. His self-reliance, courage, sagacity, and devotion to the cause brought confidence then just as it inspires reverence now.

– James I. Robertson, Jr., Alumni Distinguished Professor of History, Virginia Tech; Member of the Board, Jubal A. Early Preservation Trust

Early was an outspoken believer in white supremacy and despised the abolitionists. In the preface to his memoirs, Early wrote about African Americans as "barbarous natives of Africa" whom he believed were "in a civilized and Christianized condition" as a result of their enslavement. He continued:

The Creator of the Universe had stamped them, indelibly, with a different color and an inferior physical and mental organization. He had not done this from mere caprice or whim, but for wise purposes. An amalgamation of the races was in contravention of His designs or He would not have made them so different. This immense number of people could not have been transported back to the wilds from which their ancestors were taken, or, if they could have been, it would have resulted in their relapse into barbarism. Reason, common sense, true humanity to the black, as well as the safety of the white race, required that the inferior race should be kept in a state of subordination. The conditions of domestic slavery, as it existed in the South, had not only resulted in a great improvement in the moral and physical condition of the negro race, but had furnished a class of laborers as happy and contented as any in the world.[6]

In memoriam

The boat at White's Ferry, the only ferry still operating on the Potomac River, is named General Jubal A. Early.[7] There is also a major thoroughfare in Winchester, Virginia, named "Jubal Early Drive".

In popular media

Early was portrayed by MacIntyre Dixon in the 1993 film Gettysburg, based on Michael Shaara's novel, The Killer Angels, but appears only in the Director's Cut release.

On the science fiction series Firefly, a sadistic bounty hunter named Jubal Early appears in the last episode, "Objects in Space".

Jubal Early was the name of the character portrayed by Pat Morita, the self proclaimed "Handyman" assistant to Jean-Claude Van Damme's lead character, in the 1999 film Inferno, also known in the UK as Desert Heat.[8]

Jubal Early is very briefly mentioned on the first page of Sam's side of Only Revolutions by Mark Z. Danielewski.

See also

- List of American Civil War generals

References

- Early, Jubal A., and Gallagher, Gary W., A Memoir of the Last Year of the War for Independence in the Confederate States of America, University of South Carolina Press, 2001, ISBN 1-57003-450-8.

- Eicher, John H., and Eicher, David J., Civil War High Commands, Stanford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Gallagher, Gary W., Jubal A. Early, the Lost Cause, and Civil War History: A Persistent Legacy (Frank L. Klement Lectures, No. 4), Marquette University Press, 1995, ISBN 0-87462-328-6.

- Gallagher, Gary W., Ed., Struggle for the Shenandoah: Essays on the 1864 Valley Campaign, Kent State University Press, 1991, ISBN 0-87338-429-6.

- Gallagher, Gary W. and Alan T. Nolan (ed.), The Myth of the Lost Cause and Civil War History, Indiana University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-253-33822-0.

- Tagg, Larry, The Generals of Gettysburg, Savas Publishing, 1998, ISBN 1-882810-30-9.

- Ulbrich, David, "Lost Cause", Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, Heidler, David S., and Heidler, Jeanne T., eds., W. W. Norton & Company, 2000, ISBN 0-393-04758-X.

Notes

- ↑ Ulbrich, p. 1221.

- ↑ Early, Ruth Hairston, The Family of Early: Which Settled Upon the Eastern Shore of Virginia and Its Connection with Other Families, Brown-Morrison, 1920, pp. 107-08.

- ↑ Official Records, War of the Rebellion, 43:1:1020.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Gallagher (2000), p. 12.

- ↑ Ulbrich, p. 1222.

- ↑ Early and Gallagher, pp. xxv-xxvi.

- ↑ White's Ferry website.

- ↑ Film cast, IMDB.

Further reading

- Leepson, Marc, Desperate Engagement: How a Little-Known Civil War Battle Saved Washington, D.C., and Changed American History, Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin's Press, 2007, ISBN 0-312-36364-8.

External links

- General Jubal Early Homeplace Preservation

- Jubal Early biography centering on his Civil War years

- Online text of A memoir of the last year of the war for independence, by Jubal Early

- Online text of Autobiographical Sketch and Narrative of the War Between the States

- Online text of Douglas S. Freeman's 1934 biography of Robert E. Lee

|

||||||||||||||