Josip Broz Tito

|

Josip Broz Tito

Јосип Броз Тито GCB OMRI GColSE GColIH |

|

|

|

|

2nd President of SFR Yugoslavia

|

|

|---|---|

| In office 14 January 1953 – 4 May 1980 |

|

| Prime Minister | Himself (1945-1963) Petar Stambolić (1963-1967) Mika Špiljak (1967-1969) Mitja Ribičić (1969-1971) Džemal Bijedić (1971-1977) Veselin Đuranović (1977-1982) |

| Preceded by | Ivan Ribar |

| Succeeded by | Lazar Koliševski |

|

1st Prime Minister of SFR Yugoslavia

President of the Federal Executive Council |

|

| In office 29 November 1945 – 29 June 1963 |

|

| President | Ivan Ribar (1945-1953) Himself (1953-1963) |

| Preceded by | Position created |

| Succeeded by | Petar Stambolić |

|

1st Federal Secretary of People's Defence

|

|

| In office 29 November 1945 – 14 January 1953 |

|

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Position created |

| Succeeded by | Ivan Gošnjak |

|

1st Secretary General of Non-Aligned Movement

|

|

| In office 1 September 1961 – 10 October 1964 |

|

| Preceded by | Position created |

| Succeeded by | Gamal Abdel Nasser |

|

7th Chairman of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia

|

|

| In office November 1936 – 4 May 1980 |

|

| Preceded by | Milan Gorkić |

| Succeeded by | Branko Mikulić |

|

|

|

| Born | 25 May 1892 Kumrovec, Croatia-Slavonia, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | 4 May 1980 (aged 87) Ljubljana, SR Slovenia, SFR Yugoslavia |

| Nationality | Yugoslavia (Yugoslav) (ethnic Croat) |

| Political party | League of Communists of Yugoslavia (SKJ) |

| Spouse | Pelagija Broz (married and divorced) Jovanka Broz (married) |

| Domestic partner | Herta Hass Davorijanka Paunović Zdenka |

| Children | Zlatica Broz, Hinko Broz, Žarko Broz and Aleksandar Broz |

| Occupation | Machinist, revolutionary, resistance commander, statesman |

| Religion | Atheist |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia |

| Service/branch | All (supreme commander) |

| Years of service | 1914 1941-1980 |

| Rank | Marshal of Yugoslavia |

| Commands | Yugoslav Partisans Yugoslav People's Army |

| Battles/wars | World War I World War II |

| Awards | Awards and decorations |

Josip Broz Tito, GCB, OMRI, GColSE, GColIH, original name Josip Broz (Cyrillic script: Јосип Броз Тито listen 7 May 1892[note 1] – 4 May 1980) was the leader of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia from 1943 until his death in 1980. During World War II, Tito organized the anti-fascist resistance movement known as the Yugoslav Partisans. Later he was a founding member of Cominform,[1] but resisted Soviet influence (see Titoism), and became one of the founders and promoters of the Non-Aligned Movement. He supported the creation of a Yugoslav nationality and identity as a Pan-Slavic replacement of the existing nationalities in Yugoslavia, and thus, through his actions, was considered a Yugoslav.

Contents |

Early life

Pre-World War I

Josip Broz was born in Kumrovec, Croatia-Slavonia then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in the small region of Hrvatsko Zagorje.[2] He was the seventh child of Franjo and Marija Broz. His father, Franjo Broz, was a Croat, while his mother Marija (born Javeršek) was a Slovene. After spending part of his childhood years with his maternal grandfather in village of Podsreda, in 1900 he entered the primary school (four classes) in Kumrovec, he failed the 2nd grade and graduated in 1905. In 1907, moving out of the rural environment, Broz started working as a machinist's apprentice in Sisak. There, he became aware of the labor movement and celebrated 1 May - Labour Day for the first time. In 1910, he joined the union of metallurgy workers and at the same time the Social-Democratic Party of Croatia and Slavonia. Between 1911 and 1913, Broz worked for shorter periods in Kamnik, Cenkovo, Munich, and Mannheim, where he worked for the Benz automobile factory; he then went to Wiener Neustadt, Austria, and worked as a test driver for Daimler.

In the autumn of 1913, he was drafted into the Austro-Hungarian Army. He was sent to a school for non-commissioned officers and became a sergeant. In May 1914, Broz won a silver medal at an army fencing competition in Budapest. At the outbreak of World War I in 1914, he was sent to Ruma, where he was arrested for anti-war propaganda and imprisoned in the Petrovaradin fortress. In January 1915, he was sent to the Eastern Front in Galicia to fight against Russia. He distinguished himself as a capable soldier and was recommended for military decoration. On Easter 25 March 1915, while in Bukovina, he was seriously wounded and captured by the Russians.[3]

Prisoner and revolutionary

After thirteen months at the hospital, Broz was sent to a work camp in the Ural Mountains where prisoners selected him for their camp leader. In February 1917, revolting workers broke into the prison and freed the prisoners. Broz subsequently joined a Bolshevik group. In April 1917, he was arrested again but managed to escape and participate in the July Days demonstrations in Petrograd (Saint Petersburg) on 16 July-17, 1917. On his way to Finland, Broz was caught and imprisoned in the Petropavlovsk fortress for three weeks. He was again sent to Kungur, but escaped from the train. He hid out with a Russian family in Omsk, Siberia where he met his future wife Pelagija Belousova.[3] After the October Revolution, he joined a Red Guard unit in Omsk. Following a White counteroffensive, he fled to Kirgiziya (now Kyrgyzstan) and subsequently returned to Omsk, where he married Belousova. In the spring of 1918, he joined the South Slav section of the Russian Communist Party. By June of the same year, Broz left Omsk to find work and support his family, and was employed as a mechanic near Omsk for a year. In January 1920 he and his wife made a long and difficult journey home to Yugoslavia where he arrived in September.[3]

Upon his return, Broz immediately joined the Communist Party of Yugoslavia. The CPY's influence on the political life of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was growing rapidly. In the 1920 elections the Communists won 59 seats in the parliament and became the third strongest party. Winning numerous local elections, they even gained a stronghold in the second-largest city of Zagreb, electing Svetozar Delić for mayor. The King's regime, however, would not tolerate the CPY and declared it illegal. During 1920 and 1921 all Communist-won mandates were nullified. Broz continued his work underground despite pressure on Communists from the government. As 1921 began he moved to Veliko Trojstvo near Bjelovar and found work as a machinist. In 1925, Broz moved to Kraljevica where he started working at a shipyard. He was elected as a union leader and a year later he led a shipyard strike. He was fired and moved to Belgrade, where he worked in a train coach factory in Smederevska Palanka. He was elected as Workers Commissary but was fired as soon as his CPY membership was revealed. Broz then moved to Zagreb, where he was appointed secretary of Metal Workers Union of Croatia. In 1928, he became the Zagreb Branch Secretary of the CPY. In the same year he was arrested, tried in court for his illegal communist activities, and sent to jail.[4] During his five years at Lepoglava prison he met Moša Pijade who became his ideological mentor.[4] After his release, he lived incognito and assumed a number of noms de guerre, among them Tito.[3]

In 1934 the Zagreb Provincial Committee sent Tito to Vienna where the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia had sought refuge. He was appointed to the Committee and started to appoint allies to him, among them Edvard Kardelj, Milovan Djilas, Aleksander Rankovic, and Boris Kidric. In 1935, Tito traveled to the Soviet Union, working for a year in the Balkan section of Comintern. He was a member of the Soviet Communist Party and the Soviet secret police (NKVD). In 1936, the Comintern sent "Comrade Walter" (i.e. Tito) back to Yugoslavia to purge the Communist Party there. In 1937, Stalin had the Secretary-General of the CPY, Milan Gorkić, murdered in Moscow. Subsequently Tito was appointed Secretary-General of the still-outlawed CPY.

World War II leader

Yugoslav People's Liberation War

On 6 April 1941, German, Italian, and Hungarian forces launched an invasion of Yugoslavia. Nazi Germany initiated a three-pronged drive on the Yugoslavian capital, Belgrade. Meanwhile, the Luftwaffe bombed Belgrade (Operation Punishment) and other major Yugoslavian cities. Attacked from all sides, the armed forces of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia quickly crumbled. Subsequently, on 17 April, after King Peter II and other members of the government fled the country, the remaining representatives of the government and military met with the German officials in Belgrade. They quickly agreed to end military resistance.

The terms of the armistice were extremely severe, and the Axis proceeded to dismember Yugoslavia. Germany occupied northern Slovenia, while retaining direct military administration over a rump Serbia and considerable influence over its newly created puppet state,[5] the Independent State of Croatia, which extended over much of today's Croatia and contained all of modern Bosnia and Herzegovina. Mussolini's Italy gained the remainder of Slovenia, Kosovo, and large chunks of the coastal Dalmatia region (along with nearly all its Adriatic islands). It also gained control over the newly created Montenegrin puppet state, and was granted the kingship in the Independent State of Croatia, though wielding little real power within it. Hungary dispatched the Hungarian Third Army to occupy Vojvodina in northern Serbia, and later forcibly annexed sections of Baranja, Bačka, Međimurje, and Prekmurje.[6] Bulgaria, meanwhile, annexed nearly all of the modern-day Republic of Macedonia.

Tito's first responses to the German invasion of Yugoslavia were the founding of a Military Committee within the Central Committee of the Yugoslav Communist Party 10 April 1941 and issuing a pamphlet on 1 May 1941 calling on the people to unite in a battle against occupation.[7] On 4 July 1941, after Germany launched the invasion of the Soviet Union (Operation Barbarossa),[8] Tito called a Central committee meeting which named him military commander and issued a call to arms. On the same day, Yugoslav Partisans formed the 1st Sisak Partisan Detachment, the first armed resistance unit in Europe (mostly consisting of Croats from the nearby city). Founded in the Brezovica forest near Sisak, Croatia, its creation marked the beginning of armed anti-Axis resistance in occupied Yugoslavia.

In the first period, Tito and the Partisans (promoting a pan-Yugoslav policy of tolerance) faced competition from the Serb-dominated Chetnik movement. Led by Draža Mihailović, the latter increasingly collaborated with the Axis occupation and lost its international recognition as a resistance force.[9] After a brief initial period of cooperation, the two factions quickly started fighting against each other. Gradually, the Chetniks ended up primarily fighting the Partisans[10] instead of the occupation forces, and started cooperating with the Axis in their struggle to destroy Tito's forces, receiving increasing amounts of logistical assistance (in particular, from Italy).[11] The Partisans soon began a widespread and successful guerrilla campaign and started liberating areas of Yugoslav territory. Partisan activities provoked the Germans into "retaliation" against civilians. These retaliations resulted in mass murders (for each killed German soldier, 100 civilians were to be killed and for each wounded, 50). Despite this, liberated territories such as the "Republic of Užice" were formed and fiercely defended.

In these liberated territories, the Partisans organized People's Committees to act as civilian government. The Anti-Fascist Council of National Liberation of Yugoslavia (AVNOJ), which convened in Bihać on 26 November 1942 and in Jajce on 29 November 1943, was a representative body established by the resistance in which Tito played a leading role. In the two sessions, the resistance representatives established the basis for post-war organization of the country, deciding on a federation of the Yugoslav nations. In Jajce, Tito was named President of the National Committee of Liberation.[12] On 4 December 1943, while most of the country was still occupied by the Axis, Tito proclaimed a provisional democratic Yugoslav government.

However, with the growing possibility of an Allied invasion in the Balkans, the Axis began to divert more resources to the destruction of the Partisans. More specifically, the Germans planned and executed several massive anti-Partisan offensives with the aim of destroying the Partisan headquarters and mobile field hospital. The largest of these offensives were the Battle of Neretva (which included the Chetniks fighting alongside the Germans) and the Battle of Sutjeska (the Fourth and Fifth anti-Partisan offensives), involving nearly 200,000 troops. The Battle of Sutjeska in particular came very close to encircling and eliminating the resistance, however, the highly mobile Partisan formations managed to retreat beyond the reach of the Axis each time. The Germans therefore came close to capturing or killing Tito on at least three occasions: during the 1943 Battle of Neretva (Fall Weiss); during the subsequent Battle of Sutjeska (Fall Schwarz), in which he was wounded on 9 June, and on 25 May 1944, when he barely managed to evade the Germans after the Raid on Drvar (Operation Rösselsprung), an airborne assault outside his Drvar headquarters in Bosnia.

After Tito's Partisans stood up to these intense Axis attacks between January and June 1943, and the extent of Chetnik collaboration became evident, Allied leaders switched their support from them to the Partisans. King Peter II of Yugoslavia, American President Franklin Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill joined Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin in officially recognizing Tito and the Partisans at the Tehran Conference. This resulted in Allied aid being parachuted behind Axis lines to assist the Partisans. On 17 June 1944 on the Dalmatian island of Vis, the Treaty of Vis (Viški sporazum) was signed in an attempt to merge Tito's government (the AVNOJ) with the government in exile of King Peter II. This treaty was also known as the Tito-Šubašić Agreement. As the leader of the Yugoslav forces, Tito was now personally a target for the Axis forces in occupied Yugoslavia. The Partisans were supported directly by Allied airdrops to their headquarters, with Brigadier Fitzroy Maclean playing a significant role in the liaison missions. The RAF Balkan Air Force was formed in June 1944 to control operations that were mainly aimed at aiding his forces.

On 28 September 1944,[13] the Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union (TASS) reported that Tito signed an agreement with the USSR allowing "temporary entry of Soviet troops into Yugoslav territory" which allowed the Red Army to assist in operations in the northeastern areas of Yugoslavia. With their strategic right flank secured by the Allied advance, the Partisans prepared and executed a massive general offensive which succeeded in breaking through German lines and forcing a retreat beyond Yugoslav borders. After the Partisan victory and the end of hostilities in Europe, all external forces were ordered off Yugoslav territory.

Aftermath of World War II

On 7 March 1945, the provisional government of the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia (Demokratska Federativna Jugoslavija, DFY) was assembled in Belgrade by Josip Broz Tito, while the provisional name allowed for either a republic or monarchy. This government was headed by Tito as provisional Yugoslav Prime Minister and included representatives from the royalist government-in-exile, among others Ivan Šubašić. In accordance with the agreement between resistance leaders and the government-in-exile, post-war elections were held to determine the form of government. In November 1945, Tito's pro-republican People's Front, led by the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, won the elections with an overwhelming majority. During the period, Tito evidently enjoyed massive popular support due to being generally viewed by the populace as the liberator of Yugoslavia. The Yugoslav administration in the immediate post-war period managed to unite a country that had been severely affected by ultra-nationalist upheavals and war devastation, while successfully suppressing the nationalist sentiments of the various nations in favor of tolerance, and the common Yugoslav goal. After the overwhelming electoral victory, Tito was confirmed as the Prime Minister and the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the DFY. The country was soon renamed the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia (FPRY) (later finally renamed into Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, SFRY). On 29 November 1945, King Peter II was formally deposed by the Yugoslav Constituent Assembly. The Assembly drafted a new republican constitution soon afterwards.

Yugoslavia organized an army from the Partisan movement, the Yugoslav People's Army (Jugoslavenska narodna armija, or JNA) which was, for a period, considered the fourth strongest in Europe. The State Security Administration (Uprava državne bezbednosti/sigurnosti/varnosti, UDBA) was also formed as the new secret police, along with a security agency, the Department of People's Security (Organ Zaštite Naroda (Armije), OZNA). Yugoslav intelligence was charged with imprisoning and bringing to trial large numbers of Nazi collaborators; controversially, this included Catholic clergymen due to the widespread involvement of Croatian Catholic clergy with the Ustaša regime. Draža Mihailović was found guilty of collaboration, high treason and war crimes and was subsequently executed by firing squad in July 1946.

Prime Minister Josip Broz Tito met with the president of the Bishops' Conference of Yugoslavia, Aloysius Stepinac on June 4 1945, two days after his release from imprisonment. The two could not reach an agreement on the state of the Catholic Church. Under Stepinac's leadership, the bishops' conference released a letter condemning alleged Partisan war crimes in September, 1945. The following year Stepinac was arrested and put on trial. In October 1946, in its first special session for 75 years, the Vatican excommunicated Tito and the Yugoslav government for sentencing Stepinac to 16 years in prison on charges of assisting Ustaše terror and of supporting forced conversions of Serbs to Catholicism.[14] Stepinac received preferential treatment in recognition of his status[15] and the sentence was soon shortened and reduced to house-imprisonment, with the option of emigration open to the archbishop. At the conclusion of the "Informbiro period", reforms rendered Yugoslavia considerably more religiously liberal than the Eastern Bloc states.

In the first post war years Tito was widely considered a communist leader very loyal to Moscow, indeed, he was often viewed as second only to Stalin in the Eastern Bloc. Yugoslav forces shot down American aircraft flying over Yugoslav territory, and relations with the West were strained. In fact, Stalin and Tito had an uneasy alliance from the start, with Stalin considering Tito too independent.

Yugoslav President

- See also: SFR Yugoslavia

Tito-Stalin split

Unlike the other new communist states in east-central Europe, Yugoslavia liberated itself from Axis domination, without any direct support from the Red Army as the others. Tito's leading role in liberating Yugoslavia not only greatly strengthened his position in his party and among the Yugoslav people, but also caused him to be more insistent that Yugoslavia gets more room to follow its own interests than other Bloc leaders who had more reasons (and pressures) to recognize Soviet efforts in helping them liberate their own countries from Axis control. This had already led to some friction between the two countries before World War II was even over. Although Tito was formally an ally of Stalin after World War II, the Soviets had set up a spy ring in the Yugoslav party as early as 1945, giving way to an uneasy alliance.

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, there occurred several armed incidents between Yugoslavia and the Western Allies. Following the war, Yugoslavia recovered the territory of Istria, as well as the cities of Zadar and Rijeka that had been taken by Italy in the 1920s. Yugoslav leadership was looking to incorporate Trieste into the country as well, which was opposed by the Western Allies. This led to several armed incidents, notably air attacks of Yugoslav fighter planes on U.S. transport aircraft, causing bitter criticism from the west. From 1945 to 1948, at least four US aircraft were shot down.[16] Stalin was opposed to these provocations, as he felt the USSR unready to face the West in open war so soon after the losses of World War II. In addition, Tito was openly supportive of the Communist side in the Greek Civil War, while Stalin kept his distance, having agreed with Churchill not to pursue Soviet interests there. In 1948, motivated by the desire to create a strong independent economy, Tito modeled his economic development plan independently from Moscow, which resulted in a diplomatic escalation followed by a bitter exchange of letters in which Tito affirmed that

The Soviet answer on May 4 admonished Tito and the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (CPY) for failing to admit and correct its mistakes, and went on to accuse them of being too proud of their successes against the Germans, maintaining that the Red Army had saved them from destruction. Tito's response on May 17 suggested that the matter be settled at the meeting of the Cominform to be held that June. However, Tito did not attend the second meeting of the Cominform, fearing that Yugoslavia was to be openly attacked. At this point the crisis nearly escalated into an armed conflict, as Hungarian and Soviet forces were massing on the northern Yugoslav frontier.[18] On June 28, the other member countries expelled Yugoslavia, citing "nationalist elements" that had "managed in the course of the past five or six months to reach a dominant position in the leadership" of the CPY. The expulsion effectively banished Yugoslavia from the international association of socialist states, while other socialist states of Eastern Europe subsequently underwent purges of alleged "Titoists". Stalin took the matter personally – for once, and attempted to unsuccessfully assassinate Tito on several occasions. In a correspondence between the two leaders, Tito openly wrote:

"Stop sending people to kill me. We've already captured five of them, one of them with a bomb and another with a rifle (...) If you don't stop sending killers, I'll send one to Moscow, and I won't have to send a second." [19]

However, Tito used the estrangement from the USSR to attain US aid via the Marshall Plan, as well as to involve Yugoslavia in the Non-Aligned Movement, in which he assured a leading position for Yugoslavia. The event was significant not only for Yugoslavia and Tito, but also for the global development of socialism, since it was the first major split between Communist states, casting doubt on Comintern's claims for socialism to be a unified force that would eventually control the whole world, as Tito became the first (and the only successful) socialist leader to defy Stalin's leadership in the COMINFORM. This rift with the Soviet Union brought Tito much international recognition, but also triggered a period of instability often referred to as the Informbiro period. Tito's form of communism was labeled "Titoism" by Moscow, which encouraged purges against suspected "Titoites'" throughout the Eastern bloc.

On 26 June 1950, the National Assembly supported a crucial bill written by Milovan Đilas and Tito about "self-management" (samoupravljanje): a type of independent socialism that experimented with profit sharing with workers in state-run enterprises. On 13 January 1953, they established that the law on self-management was the basis of the entire social order in Yugoslavia. Tito also succeeded Ivan Ribar as the President of Yugoslavia on 14 January 1953. After Stalin's death Tito rejected the USSR's invitation for a visit to discuss normalization of relations between two nations. Nikita Khrushchev and Nikolai Bulganin visited Tito in Belgrade in 1955 and apologized for wrongdoings by Stalin's administration.[20] Tito visited the USSR in 1956, which signaled to the world that animosity between Yugoslavia and USSR was easing.[21] However, the relationship between the USSR and Yugoslavia would reach another low in the late 1960s. Commenting on the crisis, Tito concluded that:

"To say the least - it was a disloyal, non-objective attitude towards our Party and our country. It's a consequence of a terrible delusion that has been blown up to monstrous dimensions in order to destroy the reputation of our Party and its leadership, to take away the glory of the Yugoslavian people and their struggle. To trample everything great that our nation achieved with great sacrifices and blood loss - in order to break the unity of our Party, which represents a guarantee for successful development of socialism in our country and for the establishment of happiness of our people."

Non-aligned Yugoslavia

- See also: Non-Aligned Movement

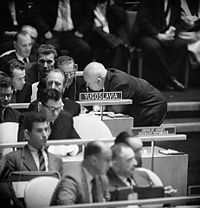

Under Tito's leadership, Yugoslavia became a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement. In 1961, Tito co-founded the movement with Egypt's Gamal Abdel Nasser, India's Jawaharlal Nehru, Indonesia's Sukarno and Ghana's Kwame Nkrumah, in an action called The Initiative of Five (Tito, Nehru, Nasser, Sukarno, Nkrumah), thus establishing strong ties with third world countries. This move did much to improve Yugoslavia's diplomatic position.

On 7 April 1963, the country changed its official name to the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Reforms encouraged private enterprise and greatly relaxed restrictions on freedom of speech and religious expression.[22] In 1966 an agreement with the Vatican, spawned by the death of Stepinac in 1960 and the decisions of the Second Vatican Council, was signed according new freedom to the Yugoslav Roman Catholic Church, particularly to teach the catechism and open seminaries. The agreement also eased tensions, which had prevented the naming of new bishops in Yugoslavia since 1945. Tito's new socialism met opposition from traditional communists culminating in conspiracy headed by Aleksandar Ranković.[23] In the same year Tito declared that Communists must henceforth chart Yugoslavia's course by the force of their arguments (implying a granting of freedom of discussion and an abandonment of dictatorship). The state security agency (UDBA) saw its power scaled back and its staff reduced to 5000.

On 1 January 1967, Yugoslavia was the first communist country to open its borders to all foreign visitors and abolish visa requirements.[24] In the same year Tito became active in promoting a peaceful resolution of the Arab-Israeli conflict. His plan called for Arabs to recognize State of Israel in exchange for territories Israel gained.[25]

In 1967, Tito offered Czechoslovak leader Alexander Dubček to fly to Prague on three hours notice if Dubček needed help in facing down the Soviets.[26]

In 1971, Tito was re-elected as President of Yugoslavia for the sixth time. In his speech in front of the Federal Assembly he introduced 20 sweeping constitutional amendments that would provide an updated framework on which the country would be based. The amendments provided for a collective presidency, a 22 member body consisting of elected representatives from six republics and two autonomous provinces. The body would have a single chairman of the presidency and chairmanship would rotate among six republics. When the Federal Assembly fails to agree on legislation, the collective presidency would have the power to rule by decree. Amendments also provided for stronger cabinet with considerable power to initiate and pursue legislature independently from the Communist Party. Džemal Bijedić was chosen as the Premier. The new amendments aimed to decentralize the country by granting greater autonomy to republics and provinces. The federal government would retain authority only over foreign affairs, defense, internal security, monetary affairs, free trade within Yugoslavia, and development loans to poorer regions. Control of education, healthcare, and housing would be exercised entirely by the governments of the republics and the autonomous provinces.[27]

Tito's greatest strength, in the eyes of the western communists, had been in suppressing nationalist insurrections and maintaining unity throughout the country. It was Tito's call for unity, and related methods, that held together the people of Yugoslavia. This ability was put to a test several times during his reign, notably during the so-called Croatian Spring (also referred to as masovni pokret, maspok, meaning "mass movement") when the government had to suppress both public demonstrations and dissenting opinions within the Communist Party. Despite this suppression, much of maspok's demands were later realised with the new constitution.

On 16 May 1974, the new Constitution was passed, and Josip Broz Tito was named President for life.

Foreign policy

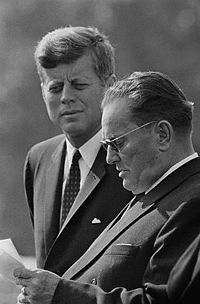

Tito was notable for pursuing a foreign policy of neutrality during the Cold War and for establishing close ties with developing countries. Tito's strong belief in self-determination caused early rift with Stalin and consequently, the Eastern Bloc. His public speeches often reiterated that policy of neutrality and cooperation with all countries is natural as long as these countries are not using their influence to pressure Yugoslavia to take sides. Relations with the United States and Western European nations were generally cordial.

Yugoslavia had a liberal travel policy permitting foreigners to freely travel through the country and its citizens to travel worldwide.[28] This was limited by most Communist countries. A number of Yugoslav citizens worked throughout Western Europe.

Tito also developed warm relations with Burma under U Nu, traveling to the country in 1955 and again in 1959, though he didn't receive the same treatment in 1959 from the new leader, Ne Win.

Because of its neutrality, Yugoslavia would often be one of the only Communist countries to have diplomatic relations with right-wing, anti-Communist governments. For example, Yugoslavia was the only communist country allowed to have an embassy in Alfredo Stroessner's Paraguay.[29] However, one notable exception to Yugoslavia's neutral stance toward anti-communist countries was Chile under Augusto Pinochet; Yugoslavia was one of many left-wing countries which severed diplomatic relations with Chile after Allende was overthrown.[30]

Final years and aftermath

- See also: Dissolution of Yugoslavia and Yugoslav wars

After the constitutional changes of 1974, Tito increasingly took the role of senior statesman. His direct involvement in domestic policy and governing was diminishing.

In January 1980, Tito was admitted to Klinični center Ljubljana (the clinical center in Ljubljana, Slovenia) with circulation problems in his legs. His left leg was amputated soon afterwards. He died there on 4 May 1980. His funeral drew many world statesmen.[31] Based on the number of attending politicians and state delegations, it was the largest statesman funeral in history.[32] They included four kings, thirty-one presidents, six princes, twenty-two prime ministers and forty-seven ministers of foreign affairs. They came from both sides of the Cold War, from 128 different countries [33].

At the time of his death, speculation began about whether his successors could continue to hold Yugoslavia together. Ethnic divisions and conflict grew and eventually erupted in a series of Yugoslav wars a decade after his death. Tito was buried in a mausoleum in Belgrade, called Kuća Cveća (The House of Flowers) and numerous people visit the place as a shrine to "better times," although it no longer holds a guard of honor.

The gifts he received during his presidency are kept in the Museum of the History of Yugoslavia (whose old names were "Museum 25. May," and "Museum of the Revolution") in Belgrade. The value of the collection is priceless: it includes works of many world-famous artists, including original prints of Los Caprichos by Francisco Goya, and many others. The Government of Serbia has planned to merge the museum into the Museum of the History of Serbia.[34]

During his life and especially in the first year after his death, several places were named after Tito. Several of these places have since returned to their original names, such as Podgorica, formerly Titograd (though Podgorica's international airport is still identified by the code TGD), which reverted to its original name in 1992. Streets in Belgrade, the capital, have all reverted back to their original pre-World War II and pre-communist names as well. In 2004, Antun Augustinčić's statue of Broz in his birthplace of Kumrovec was decapitated in an explosion.[35] It was subsequently repaired. In 2008, protests took place in Zagreb's Marshal Tito Square, with an aim to force the city government to rename it, while a counter-protest demanded that the square retain its old name. In the Croatian coastal city of Opatija the main street (also its longest street) still bears the name of Marshal Tito. Marshal Tito Street in Sarajevo is shortened but is still the main street.

Family and personal life

Tito carried out numerous affairs and was married several times.

In 1918 in Omsk, Russia Tito met Pelagija Belousova who was then fifteen; he married "Polka" a year later, and she moved with him to Yugoslavia. Polka bore him five children but only their son Žarko (born 1924) survived.[36] When Tito was jailed in 1928, she returned to Russia. After the divorce in 1936 she later remarried.

In 1936, when Tito stayed at the Hotel Lux in Moscow, he met the Austrian comrade Lucia Bauer. They married in October 1936, but the records of this marriage were later erased.[37]

His next notable relationship was with Hertha Haas, whom he married. In May 1941, she bore him a son, Aleksandar. They parted company in 1943 in Jajce during the second meeting of AVNOJ. All throughout his relationship with Haas, Tito maintained a promiscuous life and had a parallel relationship with Davorjanka Paunović, codename Zdenka, a courier and his personal secretary, who, by all accounts, was the love of his life. She died of tuberculosis in 1946 and Tito insisted that she should be buried in the backyard of the Beli Dvor, his Belgrade residence.[38]

His best known wife was Jovanka Broz (née Budisavljević). Tito was just shy of his 59th birthday, while she was 27, when they finally married in April 1952, with state security chief Aleksandar Ranković as the best man. Their eventual marriage came about somewhat unexpectedly since Tito actually rejected her some years earlier when his confidante Ivan Krajacic brought her in originally. At that time, she was in her early 20s and Tito, objecting to her energetic personality, opted for the more mature opera singer Zinka Kunc instead. Not the one to be discouraged easily, Jovanka continued working at Beli Dvor, where she managed the staff of servants and eventually got another chance after Tito's strange relationship with Zinka failed. Since Jovanka was the only female companion he married while in power, she also went down in history as Yugoslavia's first lady. Their relationship was not a happy one, however. It had gone through many, often public, ups and downs with episodes of infidelities and even allegations of preparation for a coup d'etat by the latter pair. Certain unofficial reports suggest Tito and Jovanka even formally divorced in the late 1970s, shortly before his death. However, during Tito's funeral she was officially present as Tito's wife, and later claimed rights for inheritance. The couple did not have any children.

Tito's notable grandchildren include Aleksandra Broz, a prominent theatre director in Croatia, Svetlana Broz, a cardiologist and writer in Bosnia and Josip "Joška" Broz and Eduard Broz.

Though Tito was most likely born on 7 May, he celebrated his birthday on 25 May, after he became president of Yugoslavia, to mark the occasion of an unsuccessful Nazi attempt at his life in 1944. The Germans found forged documents of Tito's, where 25 May was stated as his birthday. They attacked Tito on the day they believed was his birthday.[39]

As the leader of Yugoslavia Tito maintained a lavish life style and kept several mansions. In Belgrade he resided in the official palace, Beli dvor, and maintained a separate private residence; he spend much time at his private island of Brijuni (Brioni), an official residence from 1949 on, and at his palace at the Bled lake. His grounds at Karadjordjevo were the site of "diplomatic hunts". By 1974 Tito had 32 official residences.[40]

Tito spoke six languages in addition to his native Serbo-Croatian: Macedonian, Slovenian, Czech, German, Russian, and English.

25 May was institutionalized as the Day of Youth in former Yugoslavia. The Relay of Youth started about two months earlier, each time from a different town of Yugoslavia. The baton passed through hundreds of hands of relay runners and typically visited all major cities of the country. On 25 May of each year, the baton finally passed into the hands of Marshal Tito at the end of festivities at Yugoslav People's Army Stadium (hosting FK Partizan) in Belgrade.

Origin of the name "Tito"

A popular explanation of the sobriquet claims that it is a conjunction of two Serbo-Croatian words, "ti" (meaning "you") and "to" (meaning "that"). As the story goes, during the frantic times of his command, he would issue commands with those two words, by pointing to the person, and then task. This explanation for the name's origin is provided in Fitzroy Maclean's 1949 book, Eastern Approaches.

Tito is also an old, though uncommon, Croatian name, corresponding to Titus. Tito's biographer, Vladimir Dedijer, claimed that it came from the Croatian romantic writer, Tituš Brezovački, but the name is very well known in Zagorje. Josip Broz in one interview confirmed that this name was very common in his region, and it was the main reason for adopting it.

The newest theory is from the Croatian journalist Denis Kuljiš. He got information from a descendant of the Comintern spy Baturin, operating in Istanbul in the thirties, about a code system that was used by the latter. Josip Broz was one of his agents, and his secret nicknames were allegedly always the names of pistols. Tito himself confirmed that he used the nickname "Walter", possibly after the German Walther PPK pistol. According to Baturin, one of the last nicknames was "TT", after the Soviet TT-30 pistol, and Broz even signed a number of Communist Party documents with that name after returning to Yugoslavia. Kuljiš believes that after a few years "TT" (pronounced in Serbo-Croatian as "te te") became "Tito".

Quotes

On Brotherhood and Unity:

We have spilt an ocean of blood for the brotherhood and unity of our peoples and we shall not allow anyone to touch or destroy it from within.

None of our republics would be anything if we weren't all together; but we have to create our own history - history of United Yugoslavia, also in the future.

Without a powerful and happy Yugoslavia, there cannot be a powerful and happy Croatia.

I will give everything from myself to make sure that Yugoslavia is great, not just geographically but great in spirit, and that it hold firmly to its neutrality and sovereignty that has been established through great sacrifice in the last battle (referring to the second World War).

A decade ago young people en masse began declaring themselves as Yugoslavs. It was a form of rising Yugoslav nationalism, which was a reaction to brotherhood and unity and a feeling of belonging to a single socialist self-managing society. This pleased me greatly.

On Bosnia and Herzegovina:

Let that man be a Bosnian, Herzegovinian. Outside they don't call you by another name, except simply a Bosnian. Whether that be a Muslim (Bosniak), Serb or Croat. Everyone can be what they feel that they are, and no one has a right to force a nationality upon them.

Bosnia and Herzegovina was once a seed of division between the Croat and Serb people. Officials in Zagreb and Belgrade brought forth decisions on Bosnia-Herzegovina - decisions involving its wealth and decisions to exploit the country even more; but they didn't care about what their decisions would do to the people living in Bosnia-Herzegovina. They, for the sake of achieving their goals, pitted one people against the other.

During the war, a battle was fought here, not only for the creation of a new Yugoslavia, but also a battle for Bosnia and Herzegovina as a sovereign republic. To some generals and leaders their position on this was not quite clear. I never once doubted my stance on Bosnia. I always said that Bosnia and Herzegovina cannot belong to this or that, only to the people that lived there since the beginning of time.

Awards and decorations

Tito received many awards and decorations both from his own country and from other countries. Most notable of these (with defunct awards in italics) are:

Yugoslav awards and decorations

| Award or decoration | Country | Date | Place | Remarks | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order of the National Hero of Yugoslavia (Awarded three times) |

6 November 1944, 15 May 1972, 16 May 1977 |

Jajce, Belgrade, Belgrade |

Only person to receive it three times. | [41] | |

| Order of the Yugoslavian Great Star | 1 February 1954 | Belgrade | Highest national order of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. | [41] | |

| Order of Freedom | 12 June 1945 | Belgrade | Highest military order of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. | [41] | |

| Order of the Hero of Socialist labour | 1950 | Belgrade | [41] | ||

| Order of National Liberation | 15 August 1943 | Jajce | [41] | ||

| Order of the War flag | 29 December 1951 | Belgrade | [41] | ||

| Order of the Yugoslav Flag with Sash | 26 November 1947 | Belgrade | [41] | ||

| Order of the Partisan Star with Golden Wreath | 15 August 1943 | Jajce | [41] | ||

| Order of the Republic with Golden Wreath | 2 July 1960 | Belgrade | [41] | ||

| Order of merits for the people with golden star | 9 June 1945 | Belgrade | [41] | ||

| Order of the brotherhood and unity with golden wreath | 15 August 1943 | Jajce | [41] | ||

| Order of the National Army with Laurel Wreath | 29 December 1951 | Belgrade | [41] | ||

| Order of Military Merit with Great Star | 29 December 1951 | Belgrade | [41] | ||

| Order of Courage | 15 August 1943 | Jajce | [41] | ||

| Commemorative Medal of the Yugoslav Partisans - 1941 | 14 September 1944 | Jajce | [41] | ||

| "30 Years of Victory over Fascism" Medal | 9 May 1975 | Belgrade | [41] | ||

| "10 Years of Yugoslav Army" Medal | 22 December 1951 | Belgrade | [41] | ||

| "20 Years of Yugoslav Army" Medal | 22 December 1961 | Belgrade | [41] | ||

| "30 Years of Yugoslav Army" Medal | 22 December 1971 | Belgrade | [41] |

International awards and decorations

| Award or decoration | Country | Date | Place | Remarks | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order of the Grand Star for Exceptional Merit of the Republic of Austria with Sash | 9. February 1965 | Vienna | Highest Austrian order of merit. | [41] | |

| Grand Collar of the Order of Almara with Sash | 1 November 1960 | Belgrade | Highest decoration of the Kingdom of Afghanistan. | [41] | |

| Grand Cross of the Order of Léopold with Sash | 6 October 1970 | Brussels | Highest military order of Belgium. | [41] | |

| Grand Collar of the Order of the Andean Eagle | 29 September 1963 | Cochabamba | Bolivian state order. | [41] | |

| Grand Collar of the National Order of the Southern Cross | 19 September 1963 | Brasília | Brazil's highest order of merit. | [41] | |

| Order of People's Liberty 1st Class | 25 November 1947 | Sofia | Awarded for the participation in the revolutionary struggle of the Bulgarian people. | [41] | |

| Order of the 9th September 1944 1st Class with Swords | 25 November 1947 | Sofia | Awarded to Bulgarian and foreign citizens who took part in the armed insurrection of September 9, 1944. | [41] | |

| Order of Georgi Dimitrov | 22 September 1965 | Sofia | Awarded for exceptional merit. Came with the title of "People's Hero of Bulgaria". | [41] | |

| Grand Collar of the Order of Thiri Thudhamma | 6 January 1955 | Rangoon | The highest Burmese commendation (at the time). | [41] | |

| Grand Cross of the Royal Order of Cambodia 1st Class with Sash | 20 July 1956 | Brioni | Cambodian chivalric order, originally established by France (still in use). | [41] | |

| Grand Collar of National Independence | 17 January 1968 | Phnom Penh | Cambodian order. | [41] | |

| Grand Cross of the Order of Merit for Cameroon with Sash | 21 June 1967 | Brijuni | Highest order of merit of the Republic of Cameroon. | [41] | |

| Grand Collar of the Order of Merit of Republic of Chile | 24 September 1963 | Santiago | Chilean order of merit. | [41] | |

| Order of Merit of the Congo with Sash | 10 September 1975 | Belgrade | Highest order of merit in the Congo. | [41] | |

| Order of the White Lion I. Class with Collar | 22 March 1946 | Prague | The highest order of Czechoslovakia. | [41] | |

| Military Order of the White Lion "For Victory" I. Class | 22 March 1946 | Prague | Highest military order of Czechoslovakia. | [41] | |

| Knight's Order of the Elephant with Sash | 29 October 1974 | Copenhagen | Highest order of Denmark. | [42] | |

| Grand Collar of the Order of the Nile | 28 December 1955 | Cairo | Egypt's highest state honor. | [41] | |

| Grand Collar of the Order of the Queen of Sheba with Sash | 21 July 1954 | Belgrade | Ethiopian imperial order. | [41] | |

| War Medal of Saint George with Victory Leaves | 21 July 1954 | Belgrade | Military medal of Ethiopia. | [41] | |

| Medal for Defence of the Country with Five Palm Leaves | 21 July 1954 | Belgrade | Military medal of Ethiopia. | [41] | |

| Commander Grand Cross, with Collar, of the Order of the White Rose of Finland | 6 May 1963 | Belgrade | One of three highest state orders of Finland, established in 1919 by Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim. | [41] | |

| Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath with Collar and Sash | 17 October 1972 | Belgrade | British order of chivalry, awarded in Belgrade by Queen Elisabeth II. | [41] | |

| Grand Cross of the Order of the Legion of Honour 1st Class with Sash | 7 May 1956 | Paris | Highest decoration of France, awarded to Tito for extraordinary contributions in the struggle for peace. | [41] | |

| Médaille militaire | 7 May 1956 | Paris | Also received by Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Dwight D. Eisenhower. | [43] | |

| Special class of the Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of Germany with Sash | 24 June 1974 | Bonn | Highest possible class of the only general state decoration of the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany). | [41] | |

| Order of Karl Marx (Awarded two times) |

12 November 1974, 12 January 1977 |

Berlin, Belgrade |

The most important order in the German Democratic Republic, GDR (East Germany). | [41] | |

| Grand Cross of the Order of the Redeemer with Sash | 2 June 1954 | Athens | Highest decoration of Greece. | [41] | |

| Grand Cross with Star of the Order of the Hungarian Republic with Sash | 7 December 1947 | Budapest | Hungarian national order. | [41] | |

| Order of Merit of the People's Republic of Hungary 1st Class | 7 December 1947 | Budapest | Highest Hungarian order of merit. | [41] | |

| Order of the Flag of People's Republic of Hungary 1st Class with Brilliants | 14 September 1964 | Budapest | Hungarian national order. | [41] | |

| Order of Shakti | 28 December 1958 | Jakarta | Indonesian order, awarded for extraordinary bravery. | [41] | |

| Guerilla Medal | 28 December 1958 | Jakarta | Indonesian medal, crafted from the first exploded shell of the Indonesian National Revolution. | [41] | |

| Grand Collar of the Order of Pahlavi with Sash | 3 June 1966 | Baghdad | Iranian order. | [41] | |

| Commemorative Order "2,500 years of the Iranian Empire" | 14 October 1971 | Persepolis | Iranian order, commemorating 2,500 years of the Iranian Empire. | [41] | |

| Order "Al Rafidain" 1st Class with Sash | 14 August 1967 | Belgrade | Contemporary Iraqi state order. | [41] | |

| Military Order "Al Rafidain" 1st Class with Sash | 7 February 1979 | Baghdad | Contemporary Iraqi military order. | [41] | |

| Order of the Grand Cross of Merit of the Republic with Collar and Sash (Cavaliere di Gran Croce Decorato di Gran Cordone Ordine al Merito della Repubblica Italiana) |

2 October 1969 | Belgrade | Highest existing Italian order of merit, awarded to Josip Broz Tito in Belgrade. | [41] | |

| Grand Cordon of the Supreme Order of the Chrysanthemum | 8 April 1968 | Tokyo | Highest Japanese decoration for living persons. | [41] | |

| Order of the Knight of the Golden Lion of the House of Nassau with Sash | 9 October 1970 | Luxembourg | Chivalric Order of Luxembourg | [41] | |

| Collar of the Order of the Azetc Eagle | 30 March 1963 | Belgrade | Highest decoration awarded to foreigners in Mexico. | [41] | |

| Order of Suha Bator | 20 April 1968 | Ulan Bator | A national order of Mongolia. | [41] | |

| Grand Collar of the Order of Mehamedi | l April 1961 | Rabat | Moroccan order. | [41] | |

| Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Netherlands Lion | 20 October 1970 | Amsterdam | Order of the Netherlands which was first created by the first King of the Netherlands, King William I. | [41] | |

| Grand Cross with Collar of St. Olav | 13 May 1965 | Oslo | Highest Norwegian order of chivalry, founded in 1066. | [41] | |

| Grand Collar of the Order of Manuel Amador Guerrero | 15 March 1976 | Panama | The highest honour of Panama. | [41] | |

| Grand Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta with Sash (Awarded two times) |

25 June 1964, 4 May 1973 |

Warsaw, Brdo Castle |

One of Poland's highest orders. | [41] | |

| Grand Cross of the Order Virtuti Militari with Star | 16 March 1946 | Warsaw | Poland's highest military decoration for courage in the face of the enemy. | [41] | |

| Medal Zwycięstwa i Wolności 1945 | 16 March 1946 | Warsaw | 670,000 of the medals were awarded from 1958 to 1992. | [41] | |

| Krzyż Partyzancki | 16 March 1946 | Warsaw | 55,000 of the medals were awarded. | [41] | |

| Grand Collar of the Order of Saint James of the Sword with Sash | 23 October 1975 | Belgrade | Portuguese order of chivalry, founded in 1171. | [41] | |

| Grand Collar of the Order of Prince Henry with Sash | 17 October 1977 | Lisbon | Portuguese National Order of Knighthood. | [41] | |

| Order of the Victory of Socialism | 16 May 1972 | Drobeta-Turnu Severin | Highest Romanian decoration, awarded with the title of "People's Hero of Romania". | [41] | |

| Grand Cross of the Order for Civil and Military Merit of San Marino with Sash | 25 September 1967 | Belgrade | Highest Oder of San Marino. | [41] | |

| Order of Victory | 9 September 1945 | Belgrade | Highest military decoration of the Soviet Union, one of only 5 foreigners to receive it. Last person to receive the Order (without having it revoked). |

[44] | |

| Order of Suvorov 1st Class | September 1944 | Moscow | Awarded to military personnel for exceptional duty in combat operations, also received by Marshal Georgi K. Zhukov. | [41] | |

| Order of Lenin | 5 June 1972 | Moscow | Highest National Order of the Soviet Union. | [41] | |

| Order of the October Revolution | 16 August 1977 | Moscow | Second highest National Order of the Soviet Union. | [41] |

See also

- Yugoslav Partisans

- Yugoslav People's Liberation War

- Titoism

- Brotherhood and unity

- Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

- Yugoslav People's Army

- Marshal of Yugoslavia

- List of Yugoslav politicians

- List of places named after Tito

- Yugoslav Navy Yacht "Galeb"

- Jovanka Broz

Notes

- ↑ The official birth certificate states 25 May as his birth date.

References

- ↑ Ian Bremmer, The J Curve: A New Way To Understand Why Nations Rise and Fall, Page 175

- ↑ Unclassified United States NSA report mentions the hypothesis that the person born Josip Broz was not the person who became the Yugoslav leader Tito, based on an analysis of his accent in speaking Serbo-Croatian. http://www.nsa.gov/public/pdf/

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/597295/Josip-Broz-Tito

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Neill Barnett. Tito. Haus Publishing, London (2006) ISBN 1-904950-31-0, page 36-9

- ↑ Independent State of Croatia, or NDH (historical nation (1941-45), Europe) - Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ↑ Hungary - Shoah Foundation Institute Visual History Archive

- ↑ Stvaranje Titove Jugoslavije, page 84, ISBN 86-385-0091-2

- ↑ Higgins, Trumbull (1966). Hitler and Russia. The Macmillan Company. pp. 11–59, 98–151.

- ↑ 7David Martin, Ally Betrayed: The Uncensored Story of Tito and Mihailovich, (New York: Prentice Hall, 1946), 34..

- ↑ Chetnik - Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ↑ http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query2/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+yu0031)

- ↑ Rebirth in Bosnia, Time Magazine Dec 13, 1943

- ↑ Stvaranje Titove Jugoslavije, page 479, ISBN 86-385-0091-2

- ↑ Excommunicate's Interview - Time Magazine, 21 October 1946.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Air victories of Yugoslav Air Force

- ↑ http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,799003-1,00.html Letter to Comrades J. V. Stalin and V. M. Molotov, Apr 13 1948; Quoted in TIME, Aug 23, 1948

- ↑ No Words Left? 22 August 1949.

- ↑ "Untold tales of the Great Conquerors", U.S. News & World Report, 3 January 2006.

- ↑ Come Back, Little Tito 6 June 1955.

- ↑ Discrimination in a Tomb 18 June 1956.

- ↑ Socialism of Sorts 10 June 1966.

- ↑ Unmeritorious Pardon 16 December 1966.

- ↑ Beyond Dictatorship 20 January 1967.

- ↑ Still a Fever 25 August 1967.

- ↑ Back to the Business of Reform 16 August 1968.

- ↑ Yugoslavia: Tito's Daring Experiment 9 August 1971.

- ↑ Socialism of Sorts 10 June 1966.

- ↑ Paraguay: A Country Study, "Foreign Relations": "Foreign policy under Stroessner was based on two major principles: nonintervention in the affairs of other countries and no relations with countries under Marxist governments. The only exception to the second principle was Yugoslavia."

- ↑ J. Samuel Valenzuela and Arturo Valenzuela (eds.), Military Rule in Chile: Dictatorship and Oppositions, p. 316

- ↑ Josip Broz Tito Statement on the Death of the President of Yugoslavia 4 May 1980.

- ↑ Several authors; "Josip Broz Tito - Ilustrirani življenjepis", page 166

- ↑ Jasper Ridley, Tito: A Biography, page 19

- ↑ Status of the Museum of the History of Yugoslavia, B92

- ↑ U Kumrovcu Srušen I Oštećen Spomenik Josipu Brozu Titu – Nacional

- ↑ Barnett N., Tito, ibid, p39

- ↑ Barnett N., Tito, ibid, p44

- ↑ Interview with Lordan Zafranovic

- ↑ Stvaranje Titove Jugoslavije. page 436, ISBN 86-385-0091-2

- ↑ Barnett N, Tito, ibid p138

- ↑ 41.00 41.01 41.02 41.03 41.04 41.05 41.06 41.07 41.08 41.09 41.10 41.11 41.12 41.13 41.14 41.15 41.16 41.17 41.18 41.19 41.20 41.21 41.22 41.23 41.24 41.25 41.26 41.27 41.28 41.29 41.30 41.31 41.32 41.33 41.34 41.35 41.36 41.37 41.38 41.39 41.40 41.41 41.42 41.43 41.44 41.45 41.46 41.47 41.48 41.49 41.50 41.51 41.52 41.53 41.54 41.55 41.56 41.57 41.58 41.59 41.60 41.61 41.62 41.63 41.64 41.65 41.66 41.67 41.68 41.69 41.70 41.71 41.72 41.73 Bilo je časno živjeti s Titom. RO Mladost, RO Prosvjeta, Zagreb, February 1981. (pg. 102)

- ↑ Recipients of Order of the Elephant

- ↑ Recipients of Médaille militaire

- ↑ List of order of Victory recipients

Silvin Eiletz: Titova skrivnostna leta v Moskvi 1935–1940, Mohorjeva založba, Celovec 2008

Further reading

- Barnett, Neil. Tito. London: Haus Publishing, 2006 (paperback, ISBN 1-904950-31-0).

- Reviewed by Adam LeBor in the New Statesman, September 11, 2006.

- Carter, April. Marshal Tito: A Bibliography (Bibliographies of World Leaders). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1989 (hardcover, ISBN 0-313-28087-8).

- Dedijer, Vladimir. Tito. New York: Arno Press, 1980 (hardcover, ISBN 0-405-04565-4).

- Đilas, Milovan, Tito: The Story from Inside. London: Phoenix Press, 2001 (new paperback ed., ISBN 1-84212-047-6).

- MacLean, Fitzroy. Tito: A Pictorial Biography. McGraw-Hill 1980 (Hardcover, ISBN 0-07-044671-7).

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. Tito: Yugoslavia's Great Dictator, A Reassessment. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, 1992 (hardcover, ISBN 0-8142-0600-X; paperback, ISBN 0-8142-0601-8); London: C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers), 1993 (hardcover, ISBN 1-85065-150-7; paperback, ISBN 1-85065-155-8).

- Vukcevich, Boško S. Tito: Architect of Yugoslav Disintegration. Orlando, FL: Rivercross Publishing, 1995 (hardcover, ISBN 0-944957-46-3).

- West, Richard. Tito and the Rise and Fall of Yugoslavia. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1994 (hardcover, ISBN 1-85619-437-X); New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1996 (paperback, ISBN 0-7867-0332-6).

- Lorraine M. Lees. Keeping Tito Afloat - The United States, Yugoslavia, and the Cold War, 1945–1960. Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993 (paperback, ISBN 978-0-271-02650-3).

- New Power

External links

- Josip Broz Tito Reference Archive at the Marxists Internet Archive

- Tito and His People

- Titoville

- CNN Cold War - Profile: Josip Broz Tito

- Interview on book King of the Mountain: The Nature of Political Leadership

- Tito in anecdotes

- Red Star and Clenched Fist, Time magazine, 1943

- Area of Decision, Time magazine 1944

- Proletarian Proconsul, Time magazine 1946

- Remarks of Welcome by President Richard Nixon, The American Presidency Project 1971

- Remarks at the Welcoming Ceremony by President Jimmy Carter, The American Presidency Project 1978

- Unseen pictures from US Archives

- New Power

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Ivan Ribar |

President of SFR Yugoslavia 14 January 1953 – 4 May 1980¹ |

Succeeded by Lazar Koliševski as President of the Presidency of SFR Yugoslavia |

| Preceded by Drago Marušić as Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia |

President of the Federal Executive Council² 29 November 1945 – 29 June 1963 |

Succeeded by Petar Stambolić |

| New title | Secretary General of Non-Aligned Movement 1 September 1961 – 10 October 1964 |

Succeeded by Gamal Abdel Nasser |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by Milan Gorkić |

President of the Presidency of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia November 1936 - 4 May 1980 |

Succeeded by Branko Mikulić |

| Military offices | ||

| New title | Federal Secretary of People's Defence 29 November 1945 – 14 January 1953 |

Succeeded by Ivan Gošnjak |

| Marshal of Yugoslavia 30 November 1943 – 4 May 1980 |

Abolished | |

| Notes and references | ||

| 1. President for Life from 22 January 1974, died in office 2. i.e. the Prime Minister of SFR Yugoslavia |

||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||