Joseph Black

| Joseph Black | |

Mezzotint engraving after Sir Henry Raeburn

|

|

| Born | 16 April 1728 Bordeaux, France |

|---|---|

| Died | 6 December 1799 Edinburgh |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Fields | Medicine, physics, and chemistry |

| Doctoral students | James Watt |

| Known for | Latent heat, specific heat, and the discovery of carbon dioxide |

Joseph Black (16 April 1728 – 6 December 1799[1]) was a Scottish physicist and chemist, known for his discoveries of latent heat, specific heat, and carbon dioxide. He was a founder of thermochemistry who developed many pre-thermodynamics concepts, such as heat capacity, and was the mentor for James Watt. The chemistry buildings at both the University of Edinburgh and the University of Glasgow are named after him.

Contents |

Early years

Black was born in Bordeaux, France, where his father, who was from Belfast, Ireland, was engaged in the wine trade. His mother was from Aberdeenshire, Scotland, and her family was also in the wine business. Joseph had twelve brothers and sisters.[2] He entered the University of Glasgow when he was eighteen years old, and four years later he went to Edinburgh to further his medical studies.

Professional life

While at the University of Edinburgh, Black studied properties of carbon dioxide (CO2).[3] One of his experiments involved placing a flame and mice into the carbon dioxide. Because both entities died, Black concluded that the air was not breathable. He named it 'fixed air' in 1754. In 1756 Black described how carbonates become more alkaline when they lose carbon dioxide, whereas the taking-up of carbon dioxide reconverts them. He was the first person to isolate carbon dioxide in a perfectly pure state. This was an important step in the history of chemistry as it helped people to realize that air was not an element, but rather was composed of many different things. Black's work also aided in discrediting the belief in a fiery principle called phlogiston.

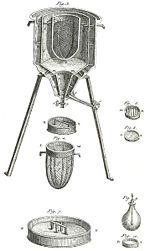

In about 1750, Joseph Black developed the analytical balance based on a light-weight beam balanced on a wedge-shaped fulcrum. Each arm carried a pan on which the sample or standard weights was placed. It far exceeded the accuracy of any other balance of the time and became an important scientific instrument in most chemistry laboratories.[4].

In 1757, he was appointed Regius Professor of the Practice of Medicine at the University of Glasgow.

In 1761, wrote Ogg, Black deduced that the application of heat to ice does not cause its immediate liquefaction, rather the ice absorbed the heat without a rise in temperature.[5] Additionally, Black observed that the application of heat to boiling water does not result in immediate evaporation. From these observations, he concluded that the heat applied must have combined with the ice particles and boiling water and become latent. In espousing his theory of latent heat, said Ogg, the new subject of thermal science commenced.[6]

Black's theory of latent heat was one of his more-important scientific contributions, and one on which his scientific fame chiefly rests. He also showed that different substances have different specific heats. This all proved important not only in the development of abstract science but in the development of the steam engine.[7]

Personal life

Black was a friend of James Watt, who first began his studies on steam power at Glasgow University in 1761. Black also was a member of the Poker Club and associated with David Hume, Adam Smith, and the literati of the Scottish Enlightenment. Black never married. He died in Edinburgh at the age of 71, and is buried there in Greyfriars Kirkyard.

See also

- Calorimetry

- Heat

- Pneumatic chemistry

- Thermochemistry

- Thermodynamics

- Timeline of hydrogen technologies

References

- ↑ Guerlac, Henry (1970-80). "Black, Joseph". Dictionary of Scientific Biography 2. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. 173-183. ISBN 0684101149.

- ↑ Lenard, Philipp (1950). Great Men of Science. London: G. Bell and Sons. pp. 129. ISBN 0-8369-1614-X. (Translated from the second German edition)

- ↑ "Experiments upon Magnesia Alba, Quick-Lime, and some other Alkaline Substances". Retrieved on 2008-03-08.

- ↑ "Equal Arm Analytical Balances". Retrieved on 2008-03-08.

- ↑ Ogg, David (1965). Europe of the Ancien Regime: 1715-1783. Harper & Row.

- ↑ Ogg, David (1965). Europe of the Ancien Regime: 1715-1783. Harper & Row. pp. 117 and 283.

- ↑ Ogg, David (1965). Europe of the Ancien Regime: 1715-1783. Harper & Row. pp. 283.

Further reading

- "JOSEPH BLACK and the discovery of carbon dioxide.", Med. J. Aust. 44 (23): 801-2, 1957, 1957 Jun 8, PMID:13440275, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13440275

- "Joseph Black--rediscoverer of fixed air.", JAMA 196 (4): 362-3, 1966, 1966 Apr 25, PMID:5325596, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5325596

- Breathnach, C S (1999), "Irish links of the multinational chemist Joseph Black (1728-1799).", Journal of the Irish Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons 28 (4): 228-31, 1999 Oct, PMID:11624012, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11624012

- Breathnach, C S (2000), "Joseph Black (1728-1799): an early adept in quantification and interpretation.", Journal of medical biography 8 (3): 149-55, 2000 Aug, PMID:10954923, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10954923

- Buchanan, W W; Brown, D H (1980), "Joseph Black (1728-1799): Scottish physician and chemist.", The Practitioner 224 (1344): 663-6, 1980 Jun, PMID:6999492, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6999492

- Buess, H (1956), "[Joseph Black (1728-1799) and the original chemical experimental research in biology and medicine.]", Gesnerus 13 (3-4): 165-89, PMID:13397909, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13397909

- Donovan, A (1978), "James Hutton, Joseph Black and the chemical theory of heat.", Ambix 25 (3): 176-90, 1978 Nov, PMID:11615707, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11615707

- Eklund, J B; Davis, A B (1972), "Joseph Black matriculates: medicine and magnesia alba.", Journal of the history of medicine and allied sciences 27 (4): 396-417, 1972 Oct, PMID:4563352, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4563352

- Foregger, R (1957), "Joseph Black and the identification of carbon dioxide.", Anesthesiology 18 (2): 257-64, PMID:13411612, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13411612

- Frackleton, W G (1953), "Joseph Black and some aspects of medicine in the eighteenth century.", The Ulster medical journal 22 (2): 87-99, 1953 Nov 1, PMID:13217111, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13217111

- Guerlac, H (1957), "Joseph Black and fixed air. II.", Isis; an international review devoted to the history of science and its cultural influences 48 (154): 433-56, 1957 Dec, PMID:13491209, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13491209

- Lenard, Philipp (1950). Great Men of Science. London: G. Bell and Sons. pp. 129. ISBN 0-8369-1614-X.

- Perrin, C E (1982), "A reluctant catalyst: Joseph Black and the Edinburgh reception of Lavoisier's chemistry.", Ambix 29 (3): 141-76, 1982 Nov, PMID:11615908, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11615908

- Ramsay, William (1905). The Gases of the Atmosphere. London: Macmillan.

External links

- Black's experiments on Alkaline Substances

- Joseph Black – Biographical information

- Joseph Black – Encyclopedia Britannica, 1911