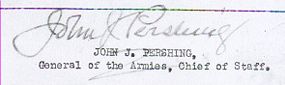

John J. Pershing

| John Joseph Pershing | |

|---|---|

| September 13, 1860 – July 15, 1948 (aged 87) | |

|

|

| Nickname | Black Jack |

| Place of birth | Laclede, Missouri |

| Place of death | Washington, D.C. |

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/branch | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1886 - 1924 |

| Rank | General of the Armies |

| Commands held | 8th Brigade American Expeditionary Force US First Army Army Chief of Staff 1916 Mexican Punitive Expedition |

| Battles/wars | Indian Wars Spanish American War Philippine American War Mexican Border Service World War I |

| Awards | Distinguished Service Cross Distinguished Service Medal Order of the Bath Légion d'honneur |

John Joseph "Black Jack" Pershing, GCB (September 13, 1860 – July 15, 1948) was an officer in the United States Army. He is the only person to be promoted in his own lifetime to the highest rank ever held in the United States Army—General of the Armies. (A retroactive Congressional edict passed in 1976[1] declared that George Washington has never been and will never be outranked[2]). Pershing led the American Expeditionary Force in World War I and was regarded as a mentor by the generation of American generals who led the United States Army in Europe during World War II, including George C. Marshall, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Omar N. Bradley, and George S. Patton.

Early life

John J. Pershing was born on a farm near Laclede, Missouri. His father, John F. Pershing, was a businessman who owned a general store. When the Civil War began, Pershing senior worked as a sutler for the 18th Missouri Volunteer Infantry Regiment, but did not serve in the military.

Pershing attended a school in Laclede that was reserved for the more intelligent children who were children of high profile citizens. As Pershing's father was well known in Laclede, Pershing and his brother attended this early form of university preparatory school.

Upon graduation from secondary school in 1878, Pershing became a local teacher and became involved with educating local African American children. In this way, although living in an atmosphere of 19th century United States racism, Pershing developed an understanding of racial issues that would later come to play in his military career when he commanded a racially diverse unit of soldiers.

Between 1880 and 1882, Pershing attended the North Missouri Normal School (now Truman State University) in Kirksville, Missouri. In 1882, he applied to the United States Military Academy after hearing that West Point offered excellent college level education. Pershing later admitted that a desire to serve in military was secondary to attending West Point and that he mainly applied to the school because the education offered was better than that of rural Missouri.

West Point years

John J. Pershing was sworn in as a West Point cadet in the fall of 1882. He was selected early for leadership and rose to become First Corporal, First Sergeant, First Lieutenant, and First Captain, the highest possible cadet rank at West Point. Cadet First Captain Pershing commanded ex officio the West Point Honor Guard that escorted the funeral of President Ulysses S. Grant.

Pershing graduated from West Point in the summer of 1886 and was commended by the Superintendent of West Point, General Wesley Merritt, as having high leadership skills and possessing "superb ability".

Just prior to graduation, Pershing briefly considered petitioning the Army to let him study law and delay his commission. He applied for a furlough from West Point, but soon withdrew the request in favor of active Army duty. He was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the United States Army in the fall of 1886, at the age of twenty six, graduating 30th in a class of 77 from West Point.

Early career

Pershing reported for active duty on September 30, 1886, and was assigned to Troop L of the 6th U.S. Cavalry stationed at Fort Bayard, in the New Mexico Territory. While serving in the 6th Cavalry, Pershing participated in several Indian campaigns and was cited for bravery for actions against the Apache.

Between 1887 and 1890, Pershing served with the 6th Cavalry at various postings in California, Arizona, and North Dakota. He also became an expert marksman and, in 1891, was rated second in pistol and fifth in rifle out of all soldiers in the U.S. Army.

On December 9, 1890, Pershing and the 6th Cavalry arrived at Sioux City, Iowa where Pershing played a role in suppressing the last uprisings of the Lakota (Sioux) Indians. He participated as 2nd Lieutenant in the Wounded Knee Massacre.

A year later, he was assigned as an instructor of military tactics at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Pershing would hold this post until 1895, but was not promoted, remaining as a second lieutenant at the age of 35.

While in Nebraska, Pershing also attended law school and graduated in 1893. Additionally, he formed a drill company, Company A, in 1891 that won the Omaha Cup. In 1893, Company A became a fraternal organization, changing its name to the Varsity Rifles. The group changed its name for the last time in 1894, renaming itself the Pershing Rifles in honor of its founder.

On October 1, 1895, Pershing was promoted to first lieutenant and took command of a troop of the 10th Cavalry Regiment (one of the original Buffalo Soldier regiments), composed of African-American soldiers under European-American officers. From Fort Assinniboine in north central Montana, he commanded an expedition to the south and southwest that rounded up and deported a large number of Cree Indians to Canada. Though, like most of the nation at the time, he was unsympathetic to Native Americans, Pershing was an outspoken advocate of the value of African American soldiers in the U.S. military.

In 1897, Pershing became an instructor at West Point, where he joined the tactical staff. While at West Point, cadets upset over Pershing's harsh treatment and high standards took to calling him "Nigger Jack", in reference to his service with the 10th Cavalry. This was softened (or sanitized) to the more euphonic "Black Jack" by reporters covering Pershing during World War I.

Spanish and Philippine-American wars

Upon the outbreak of the Spanish-American War, First Lieutenant Pershing (then 38 years old) was offered a brevet rank and commissioned a Major of Volunteers on August 26 1898. He fought with distinction at Kettle and San Juan Hill in Cuba and was cited for gallantry. In 1919, he was awarded the Silver Citation Star for these actions and, in 1932, the award was upgraded to the Silver Star Medal.

In March 1899, after suffering from malaria and spending a sick furlough in the United States, Pershing was put in charge of the Office of Customs and Insular Affairs which oversaw occupation forces in territories gained in the Spanish-American War, to include Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam.

When the Philippine-American War broke out, Pershing was ordered to Manila and reported for duty on August 17 1899. He was assigned to the Department of Mindanao and Jolo and commanded efforts to suppress the Philippine resistance. On November 27 1900, Pershing was appointed Adjutant General of his department and served in this posting until March 1 1901. He was cited for bravery for actions on the Cagayan River while attempting to destroy a Philippine stronghold at Macajambo.

In the spring of 1901, Pershing's brevet commission was revoked and he reassumed his rank as captain in the Regular Army. He served with the U.S. 1st Cavalry Regiment in the Philippines, continuing actions against the Philippine resistance. He later joined the U.S. 15th Cavalry Regiment where he served as an intelligence officer, participating in actions against the Moros, where he was cited for bravery once again at Lake Lanao. In June 1901, he also briefly served as Commander of Camp Vicars in Lanao, Philippines, after the previous camp commander had been promoted to brigadier general.

Rise to General

In June 1903, Pershing was ordered to return to the United States. He was forty-three years old and still a captain in the U.S. Army. President Theodore Roosevelt, taken by Pershing's ability, petitioned the Army General Staff to promote Pershing to colonel. At the time, Army officer promotions were based primarily on seniority, rather than merit, and although there was widespread acknowledgment that Pershing should serve as a colonel, the Army General Staff declined to change their seniority-based promotion tradition just to accommodate Pershing. They would not consider a promotion to lieutenant colonel or even major. This angered Roosevelt, but since the President could only name and promote army officers in the General ranks, his options for recognizing Pershing through promotion were limited.

In 1904, Pershing was assigned as the Assistant Chief of Staff of the Southwest Army Division stationed at Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. In October 1904, he attended the Army War College and then was ordered to Washington, D.C. for "general duties unassigned". Since Theodore Roosevelt could not yet promote Pershing, he petitioned the United States Congress to authorize a diplomatic posting and Pershing was stationed as military attaché in Tokyo in 1905. Also, in 1905, Pershing married Helen Frances Warren, the daughter of powerful U.S. Senator Francis E. Warren, a Wyoming Republican and chairman of the U.S. Military Appropriations Committee. Critics alleged that this union greatly helped his military career.

After serving as an observer in the Russo-Japanese War, Pershing returned to the United States in the fall of 1905. In a move that shocked the army establishment, President Roosevelt employed his presidential prerogative and nominated Pershing as a brigadier general, a move which Congress approved. In skipping three ranks and more than 835 officers senior to him, the promotion outraged ranking Army officers who would state, for the rest of their careers, that Pershing's appointment was the result of political connections and not military abilities. However, many other officers supported Pershing and believed that, based on his demonstrated ability to command combat forces, the promotion to general, while unusual, was not out of line.

In 1908, Pershing briefly served as a U.S. military observer in the Balkans, an assignment which was based out of Paris. Upon returning the United States, at the end of 1909, Pershing was assigned once again to the Philippines, an assignment which he served until 1912. While in the Philippines, he served as Commander of Fort McKinley, near Manila, and also was the governor of the Moro Province. The last of Pershing's four children was born in the Philippines and it was during this time that he became an Episcopalian.

Pancho Villa, personal tragedy and the Mexican Revolution

In January 1914, Pershing was assigned to command the Army 8th Brigade in Fort Bliss, Texas, responsible for security along the U.S.-Mexico border. In March 1916, under the command of General Frederick Funston, Pershing led the 8th Brigade on the failed 1916–17 Punitive Expedition into Mexico in search of the revolutionary leader Pancho Villa. During this time, George S. Patton served as one of Pershing's aides.

After a year at Fort Bliss, Pershing decided to bring his family there. The arrangements were almost complete, when on the morning of August 27, 1915, he received a telegram telling him of a tragic fire in the Presidio of San Francisco, where a lacquered floor blaze had rapidly spread, resulting in the smoke inhalation deaths of his wife, Helen, and three young daughters. Only his six-year-old son Warren was saved. Many who knew Pershing said he never recovered from their deaths. After the funerals at Lakeview Cemetery in Cheyenne, Wyoming, Pershing returned to Fort Bliss with his son, Warren, and his sister Mae, and resumed his duties of commanding officer.

World War I

At the start of World War I President Woodrow Wilson considered mobilizing an army to join the fight. Frederick Funston, Pershing's superior in Mexico, was being considered for the top billet as the Commander of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) when he died suddenly from a heart attack on February 19, 1917. Following America's entrance into the war, Wilson, after a short interview, named Pershing to command, a post which he retained until 1918. Pershing, who was a major general, was promoted to full general (the first since Philip Sheridan in 1888) in the National Army, and was made responsible for the organization, training, and supply of a combined professional and draft Army and National Guard force that eventually grew from 27,000 inexperienced men to two armies (a third was forming as the war ended) totalling over two million soldiers.

Pershing exercised significant control over his command, with a full delegation of authority from Wilson and Secretary of War, Newton Baker. Baker, cognizant of the endless problems of domestic and allied political involvement in military decision making in wartime gave Pershing unmatched authority to run his command as he saw fit. In turn, Pershing exercised his prerogative carefully, not engaging in issues that might distract or diminish his command. While earlier a champion of the African-American soldier, he did not champion their full participation on the battlefield, understanding Wilson's reactionary views on race and the political debts he owed to southern Democratic law makers.

During this time, George C. Marshall, who sadly saw Pershing depart for France and later came as command staff for the 1st Infantry Division, later served as one of Pershing's top assistants during and after the war. Douglas MacArthur served in turn as chief of staff of, then as a brigade commander in, and then for the final month of the war, commander of the 42nd "Rainbow" Division. Pershing's initial chief of staff was businessman James Harbord, who later took a combat command, but would work as Pershing's closest assistant for many years and remain extremely loyal to Pershing.

After departing from Fort Jay at Governors Island in New York Harbor under top secrecy in May 1917, Pershing arrived in France in June 1917. In a show of American presence, part of the 16th Infantry Regiment, lacking polish and discipline, but demonstrating much enthusiasm marched through Paris shortly after his arrival. Pausing at Lafayette's tomb he was reputed to have said the famous line "Lafayette, we are here." The morale-boosting sound bite was in fact spoken by his aide, Colonel Charles E. Stanton.[3] Token American forces were deployed in France in the fall of 1917, with an enormous tonic effect on Allied morale.

World War I: 1918 and Full American Participation

In early 1918, entire divisions were beginning to serve on the front lines alongside French troops. Pershing insisted that the AEF fight as units under American command rather than being split up by battalions to augment British and French regiments and brigades (although the U.S. 27th and 30th divisions, loaned during the desperate days of spring 1918, fought with the British/Australian/Canadian Fourth Army until the end of the war, taking part in the breach of the Hindenburg Line in October).

Due to the effects of trench warfare on soldiers' feet, in January, 1918, Pershing oversaw the creation of an improved combat boot, the "1918 Trench Boot", which became known as the "Pershing Boot" upon its introduction.[4]

American forces first saw serious action during the summer of 1918, contributing eight large divisions, alongside 24 French ones, at the Second Battle of the Marne. Along with the Fourth Army's victory at Amiens, the Franco-American victory at the Second Battle of the Marne marked the turning point of the war on the Western Front.

In August 1918, US First Army had been formed, first under Pershing's direct command and then by Hunter Liggett, when the US Second Army under Robert Bullard was created. After a quick victory at Saint-Mihiel, east of Verdun, some of the more bullish AEF commanders had hoped to push on eastwards to Metz, but this did not fit in with the plans of the Allied Supreme Commander, Marshal Foch, for three simultaneous offensives into the "bulge" of the Western Front (the other two being the Fourth Army's breach of the Hindenburg Line and an Anglo-Belgian offensive, led by Plumer's Second Army, in Flanders). Instead, the AEF was required to redeploy and, aided by French tanks, launched a major offensive northwards in very difficult terrain at Meuse-Argonne. Initially enjoying numerical odds of eight to one, this offensive eventually engaged 35 or 40 of the 190 or so German divisions on the Western Front, although to put this in perspective, around half the German divisions were engaged on the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) sector at the time.

When he arrived in Europe, Pershing had openly scorned the slow trench warfare of the previous three years on the Western Front, believing that American soldiers' skill with the rifle would enable them to avoid costly and senseless fighting over a small area of no man's land. This was regarded as unrealistic by British and French generals, and (privately) by a number of American generals such as Army Chief of Staff Tasker H. Bliss and his own Hunter Liggett. The AEF had done well in the relatively open warfare of the Second Battle of the Marne, but the eventual U.S. casualty rates against German defensive positions in the Argonne (120,000 U.S. casualties in six weeks, against 35 or 40 German divisions) were not noticeably better than those of the Franco-British offensive on the Somme two years earlier (600,000 casualties in four and a half months, versus 50 or so German divisions). More ground was gained, but then the German Army was in worse shape than in previous years.

Some writers (e.g., David Trask (1993)) have speculated that Pershing's frustration at the slow progress through the Argonne was the cause of two incidents which then ensued. Firstly, he ordered the U.S. First Army to take "the honor" of recapturing Sedan, site of the French defeat in 1870; the ensuing confusion (an order was issued that "boundaries were not to be considered binding") exposed U.S. troops to danger not only from the French on their left, but even from one another, as the 1st Division tacked westward by night across the path of the 42nd (accounts differ as to whether Douglas MacArthur was really mistaken for a German officer and arrested). Liggett, who had been away from headquarters the previous day, had to sort out the mess and implement the instructions from Supreme Commander Marshal Foch, allowing the French to recapture the city; he later recorded that this was the only time during the war in which he lost his temper.

Secondly, Pershing sent an unsolicited letter to the Allied Supreme War Council, demanding that the Germans not be given an armistice and that instead, the Allies should push on and obtain an unconditional surrender. Although in later years, many, including President Franklin D. Roosevelt, felt that Pershing had had a point, at the time, this was a breach of political authority. Pershing narrowly escaped a serious reprimand from Wilson's aide, Colonel House, and later apologized.

At the time of the Armistice, another U.S.-French offensive was due to start on 14 November, thrusting towards Metz and into Lorraine, to take place simultaneously with further BEF advances through Belgium.

In his memoirs, Pershing claimed that the U.S. breakout from the Argonne at the start of November was the decisive event leading to the German acceptance of an armistice, because it made untenable the Antwerp-Meuse line. This is probably an exaggeration; the outbreak of civil unrest and naval mutiny in Germany, the collapse of Bulgaria, Turkey, and particularly Austria-Hungary following Allied victories in Salonika, Syria, and Italy, and the Allied victories on the Western Front were among a series of events in the autumn of 1918 which made it clear that Allied victory was inevitable, and diplomatic inquiries about an armistice had been going on throughout October. President Wilson was keen to tie matters up before the mid-term elections, and the other Allies did not have the strength to defeat Germany without U.S. help, so had little choice but to follow Wilson's lead.

By the end of the war, U.S. troop strength in Europe (1.8 million or more) was slightly greater than that of the BEF (1.7m). French strength (three Army Groups, totalling 2.5m) was still greater, but much of it was deployed in quiet sectors such as Alsace, and after horrendous casualties and mutiny earlier in the war, France was only able or willing to undertake major offensives in conjunction with U.S. troops. Combatant strength was approximately 60% of these ration strengths in each case. Although the war ended before U.S. front-line strength vastly outstripped that of the other Western Allies as would happen in 1944-5, the threat of ever-greater U.S. commitment was another factor driving the German leadership to ask for an armistice.

American successes were largely credited to Pershing, and he became the most celebrated American leader of the war. Critics, however, would claim that Pershing commanded from far behind the lines and was critical of commanders who personally led troops into battle. This critique would become a sore point with Douglas MacArthur, who saw Pershing as a desk soldier, and the relationship between the two men deteriorated by the end of the war. Similar criticism of senior commanders by the younger generation of officers (the future generals of World War II) was made in the British and other armies, but in fairness to Pershing it should be noted that, although it was not uncommon for brigade commanders to serve near the front and even be killed, the state of communications in World War I made it more practical for senior generals to command from the rear. He controversially ordered his troops to continue fighting after the armistice was signed. This resulted in 3500 US casualties on the last day of the war, an act which was regarded as murder by several officers under his command[5].

Pershing gave a battlefield promotion to Lieutenant Colonel Ernest O. Thompson of Texas, a specialist in the use of machine guns. Thompson later became a lieutenant general of the Texas National Guard, a mayor of Amarillo, a member of the Texas Railroad Commission for thirty-two years, and an expert on international petroleum issues.[6]

Later career

In 1919, in recognition of his distinguished service during World War I, the U.S. Congress authorized the President to promote Pershing to General of the Armies of the United States, the highest rank possible for any member of the United States armed forces and was created especially for him and one that only he held at the time (General George Washington was posthumously promoted to this rank by President Gerald Ford in 1976). Pershing was authorized to create his insignia for the new rank, and chose to wear four gold stars for the rest of his career, which separated him from the four (temporary) silver stars worn by Army Chiefs of Staff, and even the five star General of the Army insignia worn by Marshall, MacArthur, Bradley, Eisenhower, and H. 'Hap' Arnold in World War II (Pershing outranked them all).

There was a movement to make Pershing President of the United States in 1920, but he refused to actively campaign. In a newspaper article, he said that he "wouldn't decline to serve" if the people wanted him and this made front page headlines. Though Pershing was a Republican, many of his party's leaders considered him too closely tied to the policies of the Democratic Party's President Wilson. The Republican nomination went to Senator Warren G. Harding of Ohio, who won the 1920 presidential election.

In 1921, Pershing became Chief of Staff of the United States Army, serving at this posting for three years. He created the Pershing Map, a proposed national network of military and civilian highways. The Interstate Highway System instituted in 1956 bears considerable resemblance to the Pershing map. In 1924, then 64 years old, Pershing retired from active military service, yet continued to be listed on the active duty rolls as part of his commission as General of the Armies.

On November 1, 1921 Pershing was in Kansas City to take part in the groundbreaking ceremony for the Liberty Memorial that was being constructed there. Also present that day were Lieutenant General Baron Jacques of Belgium, Admiral David Beatty of Great Britain, Marshal Ferdinand Foch of France and General Armando Diaz of Italy. One of the main speakers was Vice President Calvin Coolidge of the United States. In 1935, bas-reliefs of Pershing, Jacques, Foch and Diaz by sculptor Walker Hancock were added to the memorial.

On October 2, 1922, amidst several hundred officers, many of them combat veterans of World War I, General of the Armies, John J. "Black Jack" Pershing formally established the Reserve Officers Association (ROA) as an organization at the Willard Hotel in Washington, D.C. ROA is a 75,000-member, professional association of officers, former officers, and spouses of all the uniformed services of the United States, primarily the Reserve and United States National Guard. It is a congressionally chartered Association that advises the Congress and the President on issues of national security on behalf of all members of the Reserve Component.

During the 1930s, Pershing maintained a private life, but was made famous by his memoirs, My Experiences in the World War, which were awarded the 1932 Pulitzer Prize for history. He was also an active Civitan during this time.[7]

In 1940, Pershing was an outspoken advocate of aid for the United Kingdom during World War II. In 1944, with the creation of the new five star rank General of the Army, Pershing was acknowledged as the highest ranking officer of the United States military. When asked if this made Pershing a six star General, the then Secretary of War (Henry L. Stimson) commented that it did not, since Pershing never wore more than four stars but that Pershing was still to be considered senior to the present five star generals of World War II.

In July 1944, Pershing was visited by Free French leader General Charles de Gaulle. When Pershing, by then semi-senile, asked after the health of his old friend, Marshal Petain (now heading the pro-German Vichy regime), de Gaulle replied tactfully that when he last saw him, the Marshal was well.[8]

On July 15 1948, Pershing died at the Walter Reed Army Hospital in Washington, D.C. (his home after 1944). He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery, near the grave sites of the soldiers he commanded in Europe, after a state funeral.

Family

It was during his initial assignment in the American west that his mother died.[9] On March 16 1906, Pershing's father died.[9]

Warren Pershing, John J. Pershing's son, served in the Second World War as an advisor to Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall and ended the war as a full Colonel. He was father to two sons, Richard W. Pershing and John Warren Pershing III. Richard Pershing served as a 2nd Lieutenant in the 502nd Infantry and was killed in action on 17 February 1968 in Vietnam.[10] John Pershing III served as a special assistant to former Army Chief of Staff General Gordon R. Sullivan, and helped shape Army and Army ROTC programs nationwide.[11]

Summary of service

Dates of rank

| No Insignia in 1886 | Second Lieutenant, United States Army: August 1886 |

|

|

First Lieutenant, United States Army: October 1895 |

|

|

Brevet major of Volunteers, U.S. Army: August 1898 |

|

|

Captain, U.S. Army (reverted to permanent rank): June 1901 |

|

|

Brigadier General, United States Army: September 1906 |

|

|

Major General, United States Army: May 1916 |

|

|

General, National Army, Army of the United States: October 1917 |

|

|

General of the Armies, Army of the United States: September 3, 1919 As there was no prescribed insignia for this rank, General Pershing chose the four stars of a full general, except in gold. The rank has been argued to be equivalent to "6-star" general. According to the biography "When the Last Trumpet Sounds" by Gene Smith, Pershing never wore the rank on his uniform. |

Assignment history

- 1882: Cadet, United States Military Academy

- 1886: Troop L, Sixth Cavalry

- 1891: Professor of Tactics, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

- 1895: Commanding Officer, 10th Cavalry Regiment

- 1897: Instructor, United States Military Academy, West Point

- 1898: Major of Volunteer Forces, Cuban Campaign, Spanish-American War

- 1899: Officer-in-Charge, Office of Customs and Insular Affairs

- 1900: Adjutant General, Department of Mindanao and Jolo, Philippines

- 1901: Battalion Officer, 1st Cavalry and Intelligence Officer, 15th Cavalry (Philippines)

- 1902: Officer-in-Charge, Camp Vicars, Philippines

- 1904: Assistant Chief of Staff, Southwest Army Division, Oklahoma

- 1905: Military attaché, U.S. Embassy, Tokyo, Japan

- 1908: Military Advisor to American Embassy, France

- 1909: Commander of Fort McKinley, Manila, and governor of Moro Province

- 1914: Brigade Commander, 8th Army Brigade

- 1916: Commanding General, Mexican Punitive Expedition

- 1917: Commanding General for the formation of the National Army

- 1918: Commanding General, American Expeditionary Forces, Europe

- 1921: Chief of Staff of the United States Army

- 1924: Retired from active military service

- 1925: Chief Commissioner assigned by the United States in the arbitration case for the provinces of Tacna and Arica between Peru and Chile.

Awards and decorations

United States decorations

- Distinguished Service Cross

- Distinguished Service Medal

- World War I Victory Medal (with 15 battle clasps)

- Indian Campaign Medal

- Spanish Campaign Medal (with Silver Citation Star)

- Army of Cuban Occupation Medal

- Philippine Campaign Medal

- Mexican Service Medal

In 1932, seven years after Pershing's retirement from active service, his silver citation star was upgraded to the Silver Star Medal and he became eligible for the Purple Heart. In 1941, he was retroactively awarded the Army of Occupation of Germany Medal for service in Germany following the close of World War I.

(Does not include all foreign awards)

International awards

- Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (Britain)

- Grand Cross of the Legion of Honor (France)

- Military Medal (France)

- Croix de Guerre with Palm (France)

- Grand Cross of the Order of Leopold (Belgium)

- Croix de Guerre (Belgium)

- Virtuti Militari (Poland)

- Order of the White Lion (1st Class with Sword) (Czechoslovakia)

- Czechoslovakian War Cross

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Precious Jade (China)

- Order of the Golden Grain (1st Class) (China)

- Order of the Redeemer (Greece)

- Grand Cross of the Military Order of Savoy (Italy)

- Grand Cross of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus (Italy)

- Order of the Rising Sun (Japan)

- Medaille Obilitch (Montenegro)

- Grand Cross of the Order of Prince Danilo I (Montenegro)

- Medal of La Solidaridad (1st Class) (Panama)

- Grand Cross of the Order of the Sun (Peru)

- Order of Michael the Brave (1st Class) (Romania)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Liberator (Venezuela)

- Grand Cross of the Order of the Star of Karageorge with Swords (Serbia)

Civilian awards

- Congressional Gold Medal

- Thanks of the United States Congress

- Special Medal of the Committee of the city of Buenos Aires

Other honors

- The National Society of Pershing Rifles, founded by General Pershing, continues on today as America's premier undergraduate military fraternal organization.

- The Military Order of the World Wars was also founded by General Pershing.

- The M26 Pershing main battle tank was an American heavy tank introduced in 1945 that is widely considered the best US tank of World War II.

- Pershing Square in New York City is on E42nd Street at Park Avenue in front of Grand Central Terminal.

- Pershing Square in Downtown Los Angeles is named in honor of the General.

- Pershing Park in Washington, D.C. features the Pershing Memorial.

- 39th Street in Chicago was renamed after General Pershing as Pershing Road. The six story warehouse complex housing the War Department's General Depot of the Quartermaster Corps in Chicago had been located at 1819 W. 39th St.

- Pershing Avenue in Orlando, Florida a main artery on the city's southeast side, close to the airport.

- Pershing State Park, located between the north-central Missouri communities of Laclede and Meadville, is named in his honor.

- The Great Pershing Balloon Derby at Brookfield, Missouri is named in his honor and is held over the Labor Day weekend each year.

- The John J. Pershing Military and Naval Science Building on the campus of the University of Nebraska–Lincoln.

- At Truman State University, he is the namesake of the Pershing Society, Pershing Hall, Pershing Arena and the Pershing Scholarships.

- There is a Pershing Hall named in his honor at his alma mater, the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York.

- In honor of Pershing's service to his country, the Pershing tank and Pershing missile were later named after him.

- Nicknamed 'The Leader of All'.

- The 2nd Brigade of the 1st Cavalry Division (United States) is nicknamed "Black Jack."

- Pershing County, in the state of Nevada, is named in his honor.

- Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad named a diesel engined streamliner train after him in 1939 known as the General Pershing Zephyr.

- Various streets, civic center, schools and towns are today named in honor of John J. Pershing; including Pershing Ave. in Saint Louis, MO, Pershing Middle School in Houston, Texas, Pershing Elementary School in Berwyn, IL, and Pershing Drive in North Omaha and Florence, Nebraska. Pershing Avenue in Saint Louis was previously known as Berlin Avenue, but was fittingly changed in light of the public's displeasure with German activities at the time.

- Pershing Ave. named after him in Fort Riley, KS

- General Pershing Boulevard in Oklahoma City, on the Oklahoma State Fairgrounds, is named after him. It was formerly part of Main Street and turns into such after a mile past the Fairgrounds.

- A riderless horse was named in honor of Pershing, "Black Jack."

- Plaza Pershing was established in Zamboanga City, Philippines to honor him with his victory over Muslim insurgents.

- Pershing Arena on the Campus of Truman State University in Kirksville, MO (his former college) is named in honor of John J. Pershing.

- Pershing Road serves as the northern border to The Liberty Memorial (Official National World War I Memorial) in Kansas City, MO.

- The Boulevard Pershing is on the Western edge of Paris, France and runs past the Palais des Congrès near the Porte Maillot. Many of the major streets in the area (the XVIe arrondissement) are named after notable French military figures, including Avenue Foch, named after Marshall Foch, and at either end of Boulevard Pershing, streets named after the Marshals of France Gouvion Saint-Cyr and Koenig. It reflects the immense popularity of the American troops who first arrived in the French capital in 1916.

- The Pershing Center, a 4526-seat multi-purpose arena located in downtown Lincoln, NE, is named in honor of Pershing.

- Pershing Hall [2] on the campus of Montana State University - Northern located in Havre, Montana, is named in his honor.

- John Joseph Pershing was also a Freemason. He was a member of Lincoln Lodge No.19, Lincoln, Nebraska. [12]

See also

- Donald Smythe, Guerrilla Warrior: The Early Life of John J. Pershing (Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 1973) ISBN 0-68412-933-7

- Donald Smythe, Pershing: General of the Armies (Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1986) ISBN 0-25321-924-8

- Frank E. Vandiver, Black Jack: The Life and Times of John J. Pershing - Volume I (Texas A&M University Press, Third printing, 1977) ISBN 0-89096-024-0

- Frank E. Vandiver, Black Jack: The Life and Times of John J. Pershing - Volume II (Texas A&M University Press, Third printing, 1977) ISBN 0-89096-024-0

- Richard Goldhurst, Pipe Clay and Drill: John J. Pershing, the classic American soldier, (Reader's Digest Press, 1977)

- Yockelson, Mitchell A. (2008-05-30). Borrowed Soldiers: Americans under British Command, 1918. Foreword by John S. D. Eisenhower. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806139197.

- "When the Last Trumpet Sounds" by Gene Smith

References

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Library of Congress link: Washington held the title of "General and Commander in Chief" of the Continental Army

- ↑ Mattox | Natural Allies

- ↑ Little Tanks - The American Field Shoe [Boot]

- ↑ World War I: Wasted Lives on Armistice Day

- ↑ Ernest Othmer Thompson

- ↑ Leonhart, James Chancellor (1962). The Fabulous Octogenarian. Baltimore Maryland: Redwood House, Inc.. pp. 277.

- ↑ Roy Jenkins, Churchill: A Biography (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2001), p. 743n)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Frank E. Vandiver, Black Jack: The Life and Times of John J. Pershing - Volume I (Texas A&M University Press, Third printing, 1977) ISBN 0-89096-024-0 and Black Jack: The Life and Times of John J. Pershing - Volume II (Texas A&M University Press, Third printing, 1977) ISBN 0-89096-024-0

- ↑ Richard Warren Pershing, First Lieutenant, United States Army

- ↑ John Warren Pershing III, Colonel, United States Army

- ↑ Hamill, John et al.. Freemasonry : A Celebration of the Craft. JG Press 1998. ISBN 1572152672

External links

- Pershing Middle School in Houston, Texas

- Biography of John J. Pershing

- General of the Armies John J. Pershing

- Black Jack Pershing in Cuba

- The National Society of Pershing Rifles

- The Last Salute: Civil and Military Funeral, 1921-1969, CHAPTER IV, General of the Armies John J. Pershing, State Funeral, 15-19 July 1948 by B. C. Mossman and M. W. Stark

- John J. Pershing collection at Nebraska State Historical Society

- Borrowed Soldiers: Americans Under British Command, 1918 at Borrowed Soldiers

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Peyton C. March |

Chief of Staff of the United States Army 1921 – 1924 |

Succeeded by John L. Hines |

| Honorary titles | ||

| Preceded by William Howard Taft |

Persons who have lain in state or honor in the United States Capitol rotunda July 18 – July 19, 1948 |

Succeeded by Robert Taft |

|

|||||||