John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough

| John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough | |

|---|---|

| 6 June 1650—27 June 1722 | |

The Duke of Marlborough. Oil by Adriaen van der Werff. |

|

| Place of birth | Ashe House, Devon |

| Place of death | Windsor Lodge |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/branch | |

| Battles/wars | Monmouth Rebellion • Battle of Sedgemoor Nine Years War • Battle of Walcourt War of the Spanish Succession • Battle of Schellenberg • Battle of Blenheim • Battle of Elixheim • Battle of Ramillies • Battle of Oudenarde • Battle of Malplaquet |

| Awards | Order of the Garter |

John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough KG (26 May/24 June 1650 – 16 June 1722) (O.S)[1], was an English soldier and statesman whose career spanned the reigns of five monarchs throughout the late 17th and early 18th centuries. His rise to prominence began as a lowly page in the royal court of Stuart England, but his natural courage on the field of battle soon ensured quick promotion and recognition from his master and mentor James, Duke of York. When James became king in 1685, Churchill played a major role in crushing the Duke of Monmouth's rebellion; but just three years later, Churchill abandoned his Catholic king for the Protestant William of Orange.

Honoured at William's coronation, Churchill, now the Earl of Marlborough, served with distinction in Ireland and Flanders during the Nine Years' War. However, throughout the reign of William and Mary, their relationship with Marlborough and his influential wife Sarah, remained cool. After damaging allegations of collusion with the exiled court of King James, Marlborough was dismissed from all civil and military offices and temporarily imprisoned in the Tower of London. Only after the death of Mary, and the threat of another major European war, did Marlborough return to favour with William.

Marlborough's influence at court reached its zenith with the accession of Sarah's close friend Queen Anne. Promoted to Captain-General of British forces, and later to a dukedom, Marlborough found international fame in the War of the Spanish Succession where, on the fields of Blenheim, Ramillies and Oudenarde, his place in history as one of Europe's great generals was assured. However, when his wife fell from royal grace as Queen Anne's favourite, the Tories, determined on peace with France, pressed for his downfall. Marlborough was dismissed from all civil and military offices on charges of embezzlement, but the Duke eventually regained favour with the accession of George I in 1714. Although returned to his former offices, the Duke's health soon deteriorated and, after a series of strokes, he eventually succumbed to his illness in his bed at Windsor Lodge on 16 June 1722.

Contents |

Early life (1650–78)

Ashe House

At the end of the English Civil War, Lady Eleanor Drake was joined at her Devon home, Ashe House, by her third daughter Elizabeth, and Elizabeth's husband, Winston Churchill. Unlike his mother-in-law, who had supported the Parliamentary cause, Winston had had the misfortune of fighting on the losing side of the war for which he, like so many other cavaliers, was forced to pay recompense; in his case £446 18s.[2] This severe fine had impoverished the ex-Royalist cavalry captain whose motto Fiel Pero Desdichado (Faithful but Unfortunate) is still today used by his descendants.

Elizabeth gave birth to 12 children, only five of whom survived infancy. The eldest daughter, Arabella was born in February 1649; the eldest son, John, was born the following year on 26 May 1650 (O.S). Growing up in these impoverished conditions, with family tensions soured by conflicting allegiances, may have had a lasting impression on the young Churchill. His father's namesake, and John Churchill's biographer, Sir Winston Churchill, asserted – "[The conditions at Ashe] might well have aroused in his mind two prevailing impressions: First a hatred of poverty … and secondly, the need of hiding thoughts and feelings from those to whom their expression would be repugnant."[3]

After the Restoration of King Charles II in 1660 his father's fortunes took a turn for the better, although he remained far from prosperous.[4] In 1661, Winston became Member of Parliament for Weymouth, and as a mark of Royal favour he also received rewards for losses incurred fighting Parliament during the civil war, including the appointment as a Commissioner for Irish Land Claims in Dublin in 1662. While in Ireland, John attended the Dublin Free School, but a year later, after his father was recalled to take up the position of Junior Clerk Comptroller of the King's Household at Whitehall, his studies were transferred to St Paul's School in London. Charles' own penury, however, meant the old cavaliers received scant financial reward, but what the prodigal king could offer – which would cost him nothing – were positions at court for their progeny. So it was that in 1665, Winston Churchill's eldest daughter, Arabella, became Maid of Honour to Anne Hyde, the Duchess of York, joined some months later by her brother John, as page to her husband, James.[5][6]

Early military experience

James, Duke of York's passion for all things naval and military rubbed off on young Churchill. Often accompanying the Duke inspecting the troops in the royal parks, it was not long before the boy had set his heart on becoming a soldier himself.[7] On 14 September 1667 (O.S), he obtained a commission as ensign in the King's Own Company in the 1st Guards, later to become the Grenadier Guards.[8] His career was further advanced when in 1668, Churchill sailed for the North African outpost of Tangier, recently acquired as part of the dowry of Charles' Portuguese wife, Catherine of Braganza. In a rude contrast to life at court, Churchill stayed here for three years, gaining first-class tactical training and field experience skirmishing with the Moors.[5][9]

Back in London by February 1671, Churchill's handsome features and manner – described by Lord Chesterfield as "irresistible to either man or woman" – had soon attracted the ravenous attentions of one of the King's most noteworthy mistresses, Barbara Villiers, Duchess of Cleveland.[10] But his liaisons with the insatiable temptress were indeed dangerous. One account has it that upon His Majesty's appearance, Churchill leapt out of his lover's bed and hid in the cupboard, but the King, himself wily in such matters, soon discovered young Churchill who promptly fell to his knees – "You are a rascal," said the King, "but I forgive you because you do it to get your bread."[11]

A year later Churchill went to sea again. Whilst fighting the Dutch navy at the Battle of Solebay off the Suffolk coast in June 1672, valorous conduct aboard the Duke of York's flagship, the Prince, earned Churchill promotion (above the resentful heads of more senior officers) to a captaincy in the Lord High Admiral's Regiment.[13] The following year Churchill gained a further commendation at the Siege of Maastricht when the young captain distinguished himself as part of the 30-man forlorn hope, successfully capturing and defending part of the fortress. During this incident Churchill is credited with saving the Duke of Monmouth's life, receiving a slight wound in the process but gaining further praise from a grateful House of Stuart, as well as recognition from the House of Bourbon. King Louis XIV in person commended the deed, from which time forward bore Churchill an enviable reputation for physical courage, as well as earning the high regard of the common soldier.[14]

Although King Charles' anti-French Parliament had forced England to withdraw from the Franco-Dutch War in 1674, some English regiments remained in French service. In April Churchill was appointed to the colonelcy of one such regiment, thereafter serving with, and learning from, the great Marshal Turenne from whom, in Thomas Macaulay's words, he received 'many marks of esteem and confidence'.[15] Churchill was present at the hard-fought battles of Sinzheim and Entzheim; he may also have been present at Sasbach in June 1675, where Turenne was killed.[16]

Marriage

On his return to St James' Palace, Churchill's attention was drawn towards other matters, and to a fresh face at court. "I beg you will let me see you as often as you can," pleaded Churchill in a letter to Sarah Jennings, "which I am sure you ought to do if you care for my love … "[18] Sarah Jennings' social origins were in many ways similar to Churchill's – minor gentry blighted by debt-induced poverty. After her father died when she was eight, Sarah, together with her mother and sisters, moved to London. As Royalist supporters, the Jennings' loyalty to the crown, like the Churchill's, was repaid with court employment – by 1673, Sarah had become a Maid of Honour to the Duchess of York, Mary of Modena, second wife to James, Duke of York.[19]

Sarah was about fifteen when Churchill returned from the Continent in 1675, and he appears to have been almost immediately captivated by her charms and not inconsiderable good looks.[18] But Churchill's amorous, almost abject, missives of devotion were, it seems, received with suspicion and accusations of incredulity – his first lover, Barbara Villiers, was just moving her household to Paris, feeding doubts that he may well have been looking at Sarah as a replacement mistress rather than a fiancée.[20] "You say I pretend passion for you," protested Churchill … "I cannot imagine what you mean by it."[21] However, his persistent courtship over the coming months eventually won over the beautiful, if relatively poor, Maid of Honour. Although Sir Winston wished his son to marry the wealthy Catherine Sedley (if only to ease his own burden of debt), Colonel Churchill married Sarah secretly sometime in the winter of 1677–78, possibly in the apartments of the Duchess of York.[22]

Years of crises (1678–1700)

Diplomatic service

It was not long before Churchill was awarded his first important diplomatic mission to the Continent. Accompanied by his friend and rising politician, Sidney Godolphin, Churchill was assigned to negotiate a treaty in The Hague with the Dutch and Spanish in preparation for war – this time against France.[23] The young diplomat's essay in international statecraft proved personally successful, bringing him into contact with William, Prince of Orange, who was highly impressed by the shrewdness and courtesy of Churchill's negotiating skills.[24] The assignment had helped Churchill develop a breadth of experience that other mere soldiers were never to achieve,[24] but because of the duplicitous dealings of Charles's secret negotiations with Louis XIV (Charles had no intention of waging war against France), the mission ultimately proved abortive.[25] On his return to England, Churchill was appointed temporary rank of Brigadier-General of Foot, but hopes of promised action on the Continent proved illusory as the warring factions sued for peace and signed the Treaty of Nijmegen.[25]

When Churchill returned to England at the end of 1678 he found grievous changes in English society. The iniquities of the Popish Plot (Titus Oates' fabricated conspiracy aimed at excluding the Catholic Duke of York from the English accession), meant temporary banishment for James – an exile that would last nearly three years. Churchill was obliged to attend his master – who in due course was permitted to move to Scotland – but it was not until 1682, after Charles's complete victory over the exclusionists, that the Duke of York was allowed to return to London and Churchill's career could again prosper.[26] For his services to James, Churchill was made Baron Churchill of Eyemouth in the peerage of Scotland on 21 December 1682, and the following year appointed colonel of the King's Own Royal Regiment of Dragoons.[27]

The Churchills now combined income ensured a life of some style and comfort; as well as maintaining their residence in London (staffed with seven servants), they were also able to purchase Holywell House in St Albans where their growing family could enjoy the benefits of country life, but they were soon drawn back to court.[28] In July 1683 Colonel Churchill was sent to the Continent to conduct Prince George of Denmark to England for his arranged marriage to the 18-year-old Princess Anne. Anne lost no time in appointing Sarah – of whom she had been passionately fond since childhood – one of her Ladies of the Bedchamber. Their relationship continued to blossom, so much so that years later Sarah wrote – "To see [me] was a constant joy; and to part with [me] for never so short a time, a constant uneasiness … This worked even to the jealousy of a lover."[29] For his part, Churchill treated the princess with respectful affection and grew genuinely attached to her, assuming – in his reverence to royalty – the chivalrous role of a knightly champion.[30] From this time forward the Churchills were increasingly detached from James's inner circle and more noticeably associated with Anne, the Duke's younger daughter.[31]

Rebellion

With the death of King Charles in 1685, his brother, James, Duke of York became King James II. Urged on by malcontents and various Whig conspirators (exiled for their part in the failed Rye House plot), the illegitimate son of Charles and Lucy Walter, James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth, prepared to take what he considered rightfully his – the Protestant crown of England. Monmouth landed at Lyme Regis on 11 June (O.S).

Churchill had earlier been affirmed Gentleman of the King's Bedchamber in April, and the following month admitted to the English peerage as Baron Churchill of Sandridge in the county of Hertfordshire, but he was frustrated with his appointment as second in command to face Monmouth's rebels; the honour of leading the King’s forces instead passed to the limited, but highly loyal, Louis de Duras, 2nd Earl of Feversham. Unaware that he had just been promoted to Major-General on 3 July (O.S), Churchill complained to Lord Clarendon, "I see plainly that the trouble is mine, and that the honour will be another's."[32] Monmouth's ill-timed, ill-equipped, and ill-advised peasant rebellion eventually floundered on the Somerset field of Sedgemoor on 6 July 1685 (O.S), but although his role was subordinate to Feversham, Churchill's administrative organisation, tactical skill, and courage in battle was pivotal in the victory – the man who saved Monmouth's life at Maastricht had now brought about his demise at Sedgemoor.

As prophesised, Feversham received the lion's share of the reward. Churchill was not entirely forgotten – in August he was awarded the lucrative colonelcy of the Third Troop of Life Guards – but the witch-hunt that followed the rebellion, driven by the bloodthirsty zeal of Judge Jeffreys, sickened his sense of propriety.[33] Indeed, it may be possible that the Sedgemoor campaign, and its subsequent persecutions, set in train a process of disillusion that culminated in his abandonment of his king, and long-time patron and friend, just three short years later.[34]

Revolution

Churchill remained at court, but was anxious not to be seen as sympathetic towards the King's growing religious ardour against the Protestant establishment.[35] James's promotion of Catholics in royal institutions – including the army – engendered first suspicion, and ultimately sedition in his mainly Protestant subjects; even members of his own family expressed alarm at the King's fanatic zeal for the Roman Catholic religion.[36] Some in the King's service, such as the Earl of Salisbury and the Earl of Melfort betrayed their Protestant upbringing in order to gain favour at court, but Churchill remained true to his conscience, "I have been bred a Protestant, and intend to live and die in that communion."[37]

Seven men met to draft the invitation to William (whose wife, Mary, was another of James's daughters), to invade England. The signatories to the letter included Whigs, Tories, and a Bishop (Henry Compton), who assured the Prince of Orange that, "Nineteen parts of twenty of the people ... are desirous of change."[38] William needed no further encouragement. Although the invitation was not signed by Churchill (he was not, as yet, of significant political rank to be a signatory), he declared his intention through William's principal English contact in The Hague – "If you think there is anything else that I ought to do, you have but to command me."[39] Churchill, like many others, was looking for an opportune time to desert James.

William landed at Torbay on 5 November 1688 (O.S); from there, he moved his army to Exeter. James' forces – once again commanded by Lord Feversham – moved to Salisbury, but few of its officers were eager to fight – even James's daughter Princess Anne wrote to William to wish him "good success in this so just an undertaking."[40]

Churchill, promoted to Lieutenant-General, was still at his king's side, but displaying "the greatest transports of joy imaginable" at the desertion of Lord Cornbury, led to entreaties from Feversham for his arrest. Churchill himself had openly encouraged defection to the Orangist cause, but James continued to hesitate.[41] Soon it was too late to act. After the meeting of the council of war on the morning of 23 November (O.S), Churchill, accompanied by some 400 officers and men, slipped from the royal camp and rode towards William in Axminster. The following day, Churchill left behind him a letter of apology and self-justification: " ... I hope ... [I] may reasonably convince Your Majesty and the world that I am actuated by a higher principle ..."[42]

When the King saw he could not even keep Churchill, for so long his loyal and intimate servant, he despaired. James, who in the words of one French contemporary, had "given up three kingdoms for a Mass", fled to France, taking with him his heir, James, Prince of Wales (later known as "The Old Pretender"). With barely a shot fired, William had secured the throne, reigning as joint sovereign with James' eldest daughter, Mary.

Nine Years War

In April 1689, as part of William's coronation honours, Churchill was created Earl of Marlborough. His elevation in the peerage led to accusatory rumours from James's supporters that Marlborough had disgracefully betrayed his erstwhile King for personal gain; William himself entertained reservations about the man who had deserted James.[43] Marlborough's apologists though (including his most notable descendant Winston Churchill) have been at pains to attribute patriotic, religious, and moral motives to his action, but, in the words of historian David Chandler, it must be plainly asserted that Marlborough was also motivated by ambition and self-interest – it is difficult to absolve Marlborough of ruthlessness, ingratitude, intrigue, and treachery against a man to whom he owed virtually everything in his life and career to date.[44]

Less than six months after James' departure for the Continent, England declared war on France as part of a powerful coalition aimed at curtailing the ambitions of King Louis XIV; but throughout the Nine Years War (1688–97), Marlborough saw only three years' service in the field, and then mostly in subordinate commands. However, at Walcourt on 25 August 1689 Marlborough won praise from the Dutch commander, Prince Waldeck, – " … despite his youth he displayed greater military capacity than do most generals after a long series of wars … He is assuredly one of the most gallant men I know."[45]

When he returned to England, Marlborough was presented with further opportunities. As commander-in-chief of the forces in England he became highly knowledgeable of all the intricacies and illogicalities of the English military system, and played a major role in its reorganisation and recruitment; but since Walcourt, Marlborough's popularity at court had waned.[46] William and Mary distrusted both Lord and Lady Marlborough's influence as confidents and supporters of the Princess; so much so that a resentful Mary asked her sister to choose between herself and the King on the one hand, and the Marlboroughs on the other – unhesitantly, Anne chose the latter.[47] For the moment though, the clash of tempers were over-shadowed by more pressing events in Ireland, where James had landed in March 1689 in his attempt to regain his throne. When William left for Ireland in June 1690, Marlborough was appointed a member of the Council of Nine to advise Queen Mary in the King's absence, but she made scant effort to disguise her distaste at his appointment – "I can neither trust or esteem him," she wrote to William.[46]

William's decisive victory at the Boyne on 1 July 1690 (O.S) had forced James to abandon his army and flee back to France. After obtaining permission from William, Marlborough himself left for Ireland, capturing the ports of Cork and Kinsale in October, but he was to be disappointed in his hopes of an independent command. Although William recognised Marlborough's qualities as a soldier, he was still not disposed to fully trust anyone who had defected from King James, and loath to advance a career of a man whom he described to Lord Halifax as 'very assuming'.[48]

Dismissal and disgrace

William's bias towards Dutchmen for positions of high authority angered the English officers in the army, including Marlborough. The refusal of the Order of the Garter and failure to appoint him Master-General of the Ordnance, rankled with the ambitious Earl; nor had Marlborough concealed his bitter disappointment behind his usual bland discretion.[49] Using his influence in Parliament and the army, Marlborough aroused dissatisfaction concerning William's preferences for foreign commanders, an exercise designed to force the King's hand.[50] William, aware of this, in turn began to speak openly of his distrust of Marlborough; the Elector of Brandenburg's envoy to London overheard the King remark that he had been treated – "so infamously by Marlborough that, had he not been king, he would have felt it necessary to challenge him to a duel."[51]

King James, exiled in Saint-Germain, maintained contact with his supporters in England whose principal object was to re-establish James upon his throne. Since January 1691, Marlborough had been in contact with James, anxious to obtain the exiled King's pardon for deserting him in 1688 – a pardon essential for the success of his future career in the not altogether unlikely event of James' restoration.[52] William was well aware of these contacts (as well as others such as Godolphin and Shrewsbury), but their double-dealing was seen more in the nature of an insurance policy, rather than as an explicit commitment – a necessary element in a situation of unexampled complexity.[53] But William was conscious of Marlborough's qualities, military and political, and the danger the Earl posed, "William was not prone to fear," wrote Macaulay, "but if there was anyone on earth that he feared, it was Marlborough."[54]

By the time William and Marlborough had returned from an uneventful campaign in the Spanish Netherlands in October 1691, their relationship had further deteriorated. In January 1692, the Queen, angered by Marlborough's intrigues in Parliament, the army, and even with Saint Germain, ordered Anne to dismiss Sarah from her household – Anne refused.[55] The next day, on 20 January (O.S), the Earl of Nottingham, Secretary of State, ordered Marlborough to dispose of all his posts and offices, both civil and military, and consider himself dismissed from the army and banned from court.[56] No reasons were given but Marlborough's chief associates were outraged; the Duke of Shrewsbury voiced his disapproval and Godolphin threatened to retire from government; Admiral Russell, now commander-in-chief of the Navy personally accused the King of ingratitude to the man who had "set the crown upon his head."[57]

High treason

The nadir of Marlborough's fortunes had not yet been reached. The spring of 1692 brought renewed threats of a French invasion and new accusations of Jacobite treachery. Acting on the testimony of Robert Young, the Queen had arrested all the signatories to a letter supporting the restoration of James II and the seizure of King William. Marlborough, as one of these signatories was sent to the Tower of London on 4 May (O.S) where he languished for five weeks; his anguish compounded by the news of the death of his younger son Charles on 22 May (O.S). Young's letters were eventually discredited as forgeries and Marlborough released, but he continued his correspondence with James, leading to the celebrated incident of the "Camaret Bay letter" of 1694.[58]

For several months the Allies had been planning an attack against Brest, the French port in the Bay of Biscay. The French had received intelligence alerting them to the imminent assault, enabling Marshal Vauban to strengthen its defences and reinforce the garrison. Inevitably, the attack on 18 June, led by the English General Thomas Tollemache, ended in disaster; most of his men were killed or captured – Tollemache himself died of his wounds shortly afterwards.[59] Despite lacking evidence, Marlborough's detractors claimed that it was he who had alerted the enemy.[58][60] But although it is practically certain that Marlborough sent a message across the Channel in early May describing the impending attack on Brest, it is equally certain that the French had long learned of the expedition from another source – possibly Godolphin or the Earl of Danby.[58] Winston Churchill goes as far as to say that the letter was a forgery, but David Chandler states – "the whole episode is so obscure and inconclusive that it is still not possible to make a definite ruling. In sum, perhaps we should award Marlborough the benefit of the doubt."[61]

Reconciliation

Mary's death on 28 December 1694 (O.S), eventually led to a formal, but cool, reconciliation between William and Anne, now heir to the throne. Marlborough hoped that the rapprochement would lead to his own return to office, but although he and Lady Marlborough were allowed to return to court, the earl received no offer of employment.[61]

In 1696 Marlborough, together with Godolphin, Russell and Shrewsbury, was yet again implicated in a treasonous plot with King James, this time instigated by the Jacobite militant Sir John Fenwick. The conspiracy was eventually dismissed as a fabrication and Fenwick executed – the King himself had remained incredulous of the accusations – but it was not until 1698, a year after the Treaty of Ryswick brought an end to the Nine Years War, that the corner was finally turned in William's and Marlborough's relationship.[61] On the recommendation of Lord Sunderland (whose wife was also a close friend of Lady Marlborough), William eventually offered Marlborough the post of governor to the Duke of Gloucester, Anne's eldest son. He was also restored to the Privy Council, together with his military rank,[62] but striving to reconcile his close Tory connections with that of the dutiful royal servant was difficult, leading Marlborough to bemoan – "The King's coldness to me still continues."[63]

Later life (1700–22)

War of the Spanish Succession

With the death of the infirm and childless King Charles II of Spain on 1 November 1700, the succession of the Spanish throne, and subsequent control over her empire (including the Spanish Netherlands), once again embroiled Europe in war – the War of the Spanish Succession. On his deathbed, Charles had bequeathed his domains to King Louis XIV's grandson, Philip, Duc d'Anjou. This threatened to unite the Spanish and French kingdoms under the House of Bourbon – something unacceptable to England, the Dutch Republic, and the Austrian Emperor, Leopold I, who had himself a claim to the Spanish throne.

With William's health deteriorating (the King himself estimating he had but a short time to live), and with the Earl's undoubted influence over his successor Princess Anne, William decided that Marlborough should take centre stage in European affairs. Representing William in The Hague as Ambassador-Extraordinary, and as commander of English forces, Marlborough was tasked to negotiate a new coalition to oppose France and Spain. On 7 September 1701, the Treaty of the Second Grand Alliance was duly signed by England, the Emperor, and the Dutch Republic to thwart the ambitions of Louis XIV and stem Bourbon power.[64] William, however, was not to see England's declaration of war. On 8 March 1702 (O.S), the King, already in a poor state of health, died from injuries sustained in a riding accident, leaving his sister-in-law, Anne, to be immediately proclaimed as his successor. But although the King's death occasioned instant disarray amongst the coalition, Count Wratislaw was able to report – "The greatest consolation in this confusion is that Marlborough is fully informed of the whole position and by reason of his credit with the Queen can do everything."[65]

This 'credit with the Queen' also proved personally profitable to her long-standing friends. Anxious to reward Marlborough for his diplomatic and martial skills in Ireland and on the continent, Marlborough became the Master-General of the Ordnance – an office he had long desired – made a Knight of the Garter and Captain-General of her armies at home and abroad. With Lady Marlborough's advancements as Groom of the Stole, Mistress of the Robes, and Keeper of the Privy Purse, the Marlboroughs, now at the height of their powers with the Queen, enjoyed a joint annual income of over £60,000, and unrivalled influence at court.[66]

Early campaigns

On 4 May 1702 (O.S) England formally declared war on France. Marlborough was given command of the British, Dutch, and hired German forces, but the command had its limitations: as Captain-General he had the power to give orders to Dutch generals only when Dutch troops were in action with his own; at all other times he had to rely on the consent of accompanying Dutch field deputies or political representatives of the States-General – his ability to direct allied strategy would rely on his tact and powers of persuasion.[67] But despite being frustrated by his Dutch Allies' initial lassitude to bring the French to battle, the war began well for Marlborough who managed to out-manoeuvre the French commander, Marshal Boufflers.[68] In 1702 he had captured Venlo, Roermond, Stevensweert and Liège in the Spanish Netherlands for which, in December, a grateful Queen publicly proclaimed Marlborough a Duke and Marquess of Blandford.[69]

On 9 February 1703 (O.S), soon after the Marlboroughs' elevation, their daughter Elizabeth married Scroop Egerton, Earl of Bridgewater; this was followed in the summer by an engagement between Mary and John Montagu, heir to the Earl of, and later Duke of, Montagu, (they later married on 20 March 1705). Their two older daughters were already married: Henrietta to Godolphin's son Francis in April 1698, and Anne to the hot-headed and intemperate Charles Spencer, Earl of Sunderland in 1700.[70] However, Marlborough's hopes of founding a great dynasty of his own reposed in his eldest and only surviving son, John, who, since his father's elevation had borne the courtesy title of Marquess of Blandford. But while studying at Cambridge in early 1703, the 17 year-old was stricken with a severe strain of smallpox. His parents rushed to be by his side, but on Saturday morning, 20 February the boy died, plunging the duke into 'the greatest sorrow in the world'; he later lamented to Lord Ailesbury – "I have lost what is so dear to me."[71]

Bearing his grief, and leaving Sarah to hers, the Duke returned to The Hague at the beginning of March. By now Marshal Villeroi had replaced Boufflers as commander in the Spanish Netherlands,[72] but although Marlborough was able to take Bonn, Huy, and Limbourg in 1703, continuing Dutch hesitancy prevented him from bringing the French in Flanders to a decisive battle.[73] Domestically the Duke also encountered resistance. Both he and Godolphin were hampered by, and often at variance with, their High Tory colleagues who, rather than advocating a European policy, favoured the full employment of the Royal Navy in pursuit of trade advantages and colonial expansion overseas. For their part, the Whigs, although enthusiastic for the European strategy, had dropped all pretence at supporting the conduct of the war, accounting Marlborough and Godolphin guilty of failing to provide gains commensurate with the funds generously granted them in Parliament.[74] The moderate Tory ministry of Marlborough and Godolphin found itself caught between the political extremes. However, Marlborough, whose diplomatic tact had held together a very discordant Grand Alliance, was now a general of international repute and the limited success of 1703 was soon eclipsed by the Blenheim campaign of 1704.[75]

Blenheim and Ramillies

Pressed by the French and Bavarians to the west and Hungarian rebels to the east, Austria faced the real possibility of being forced out of the war. Concerns over Vienna and the need to ensure the continuing involvement of Emperor Leopold I in the Grand Alliance, had convinced Marlborough of the necessity of sending aid to the Danube; but the scheme of seizing the initiative from the enemy was extremely bold. From the start the Duke resolved to mislead the Dutch who would never willingly permit any major weakening of the allied forces in the Spanish Netherlands. To this end, Marlborough moved his English troops to the Moselle, (a plan approved of by The Hague), but once there, he resolved to slip the Dutch leash and march south to link up with Austrian forces in southern Germany.[77]

A combination of strategic deception and brilliant administration enabled Marlborough to achieve his purpose.[78] After covering approximately 250 miles (400 km) in five weeks, Marlborough – together with Prince Eugene of Savoy – delivered a crushing defeat of the Franco-Bavarian forces at the Battle of Blenheim on 13 August 1704. The whole campaign, which historian John Lynn describes as one of the greatest examples of marching and fighting before Napoleon, had been a model of planning, logistics, and tactical skill, the successful outcome of which had altered the course of the conflict – Bavaria and Cologne were knocked out of the war, and Louis' hopes of an early victory were destroyed.[79] The campaign continued with the capture of Landau on the Rhine, followed by Trier and Trarbach on the Moselle. With these successes, Marlborough now stood as the foremost soldier of the age; even the Tories, who had declared that should he fail they would "break him up like hounds on a hare", could not entirely restrain their patriotic admiration.[80]

The Queen lavished upon her favourite the royal manor of Woodstock and the promise of a fine palace commemorative of his great victory, but since her accession, her relationship with Sarah had become progressively distant.[81] The Duke and Duchess had risen to greatness not least because of their intimacy with Anne, but Sarah had tired of petty ceremony and formality of court life and increasingly found her mistress's company wearisome. For her part, Anne, now Queen of England and no longer the timid adolescent so easily dominated by her more beautiful friend, had grown tired of Sarah's tactless political hectoring and increasingly haughty manner.[82]

Queen Anne enthusiastically agreed to Emperor Leopold’s offer (made during the duke’s march to the Danube) to make Marlborough a prince of the Holy Roman Empire in the small principality of Mindelheim – the Bavarian estate which had been confiscated from the Elector and effectively occupied after Blenheim.[83] But after the successes of 1704, the campaign of 1705 brought little reason for satisfaction on the continent. Endless delays and evasions from his Allies had once again frustrated Marlborough's attempts at any major offensive.[84] "I find so little zeal for the common cause that it is enough to break a better heart than mine," he confided to Anthonie Heinsius.[85] Although Marlborough had been able to penetrate the Lines of Brabant in July, allied indecision had prevented the Duke from pressing his advantage.[86]

The year 1705 had provided the French time to reorganize their forces. Marshal Villars’ successes against Baden along the Rhine, and Vendome’s victory at Calcinato in Italy, had thwarted Marlborough's original plan for 1706 – a possible march to Italy to link up with Prince Eugene.[87] The Duke, however, soon adjusted his schemes. In May Marlborough marched into enemy territory, hoping to lure Marshal Villeroi into accepting battle. Equally determined to fight, and keen to avenge Blenheim, King Louis goaded his commander to seek out 'Monsieur Marlbrouck'. The subsequent Battle of Ramillies, fought in the Spanish Netherlands on 23 May 1706, was perhaps Marlborough's most successful action, one which, in the words of Villars, had caused "the most shameful, humiliating and disastrous of routs" of French forces. For the loss of less than 3,000 dead and wounded (far fewer than Blenheim), his victory had inflicted over 20,000 casualties on the enemy. Town after town fell, but although the campaign was not decisive, it was an unsurpassed operational triumph for the English general.[88] When Marlborough eventually closed down the Ramillies campaign, he had completed the conquest of almost all the Spanish Netherlands. Good news for the Allies also arrived from the Italian front – in September Prince Eugene routed the French army at Turin. After his victory at Ramillies the titular 'Charles III' offered Marlborough the governorship of the Spanish Netherlands, worth £60,000 per annum. But the Dutch, who wished to maintain their economic and political dominance in the region, found the Habsburg offer displeasing, raising suspicions of England's motives, and the Duke's in particular. It was a position Marlborough desired, but in the name of Anglo–Dutch unity, it was one he refused.[89]

Falling out of favour

While Marlborough fought in Flanders, a series of personal and party rivalries instigated a general reversal of fortune. The Whigs, who were the main prop of the war, had been laying siege to Marlborough's close friend and ally, Lord Godolphin. As a price for supporting the government in the next parliamentary session, the Whigs demanded a share of public office with the appointment of a leading member of their 'Junto', the Earl of Sunderland, to the post of Secretary of State.[90] The Queen, who loathed the Whigs, bitterly opposed the move; but Godolphin, increasingly dependent on Whig support, had little room for manoeuvre. With Sarah's tactless, unsubtle backing, Godolphin relentlessly pressed the Queen to submit to Whig demands. In despair, Anne finally relented and Sunderland received the seals of office, but the special relationship between Godolphin, Sarah, and the Queen had taken a severe blow and she began to turn increasingly to a new favourite, Abigail Masham. Anne also became ever more reliant on the advice of Godolphin's and Marlborough's fellow moderate Tory Robert Harley, who, convinced that the duumvirate's policy of appeasing the Whig Junto was unnecessary, had set himself up as alternative source of advice to a sympathetic Queen.[91]

The Allies' annus mirabilis was followed in 1707 with a resurgence in French arms in all fronts of the war, and a return to political squabbling and indecision within the Grand Alliance. Marlborough's diplomatic skill was able to prevent Charles XII, King of Sweden, from entering the war against the Empire, but Prince Eugene's retreat from Toulon, and major setbacks in Spain and in Germany had ended any lingering hopes of a war-winning blow that year.[92]

Marlborough returned to England and a political storm. The High Tories were critical of Marlborough's failure to win the war in 1707 and demanded the transfer of 20,000 troops from the Low Countries to the Spanish theatre. For their part the Whigs, infuriated by the Queen's appointment of Tory bishops, threatened to withdraw support from the government. To the Duke and Godolphin this necessitated further wooing of the Junto in order to win back their support (the Junto were full of zeal for the war and, like Marlborough, considered Spain a military sideshow).[93] Yet the more they urged the Queen to make concessions to the Whigs, the more they pushed her into Harley's hands; at every stage of this process, the wider the breach became between the Queen and her Captain-General.[94]

Oudenarde and Malplaquet

The setbacks of 1707 had lasted throughout the opening months of 1708 with the losses of Bruges and Ghent to French forces. Marlborough remained despondent about the general situation, but his optimism received a major boost with the arrival of Prince Eugene. Heartened by the Prince's robust confidence, Marlborough set about to regain the strategic initiative for the Allies. On the night of 10 July, with the French preparing to besiege Oudenarde, the Duke made a forced march to surprise the enemy. Marlborough's ensuing victory over Marshal Vendôme at the Battle of Oudenarde on 11 July 1708, had demoralised the French army in Flanders; his eye for ground, his sense of timing, and his keen knowledge of the enemy were again amply demonstrated.[95] Marlborough professed himself satisfied with the campaign, but he had become increasingly fatigued by the worsening atmosphere at court; on hearing the news of the Duke's victory the Queen initially exclaimed – "Oh Lord, when will all this bloodshed cease!"[96] Sarah also vexed the Duke. Relentlessly bombarding him with letters of complaint, he had at one point wearily replied – "I have neither spirits nor time to answer your three last letters."[97]

On 22 October Marlborough captured Lille, the strongest fortress in Europe (Boufflers yielded the city's citadel on 10 December); he also re-took Bruges and Ghent, but the Duke and Godolphin found themselves ever more uncomfortably placed between the Whig demands for office, and a Queen strongly disinclined to reconciliation. By November, the Whig Junto had gained ascendancy in British politics, reducing the Tories to an ineffective minority; but the more the Queen resisted the Whigs, the more Godolphin and Marlborough were attacked by them for not succeeding in persuading her to give way, and in turn, attacked by the Tories for endeavouring to do so.[98]

After the Oudenarde campaign, and one of the worst winters in modern history, France was on the brink of collapse.[99] However, formal peace talks broke down in April 1709 after uncompromising and exacting Whig demands were rejected by King Louis. But despite his opposition to Whig obduracy, Marlborough no longer had the support of the Queen he had once enjoyed, and, with the Whigs holding the reins of British policy, he played only a subordinate role throughout the negotiations. To compound his troubles news arrived in August of fresh trouble between the Queen and his wife; Anne had informed Sarah that finally she had had enough of her bullying, writing – "It is impossible for you to recover my former kindness … "[100]

After outwitting Marshal Villars to take the town of Tournai on 3 September, the two opposing generals finally met at the tiny village of Malplaquet on 11 September 1709.[100] On the left flank, the Prince of Orange led his Dutch infantry in desperate charges only to have it cut to pieces; on the other flank, Eugene attacked and suffered almost as severely. But sustained pressure on his extremities forced Villars to weaken his centre, thus enabling Marlborough to breakthrough and claim victory. But the cost was high; the allied casualty figures were approximately double that of the French, leading Marlborough to admit – "The French have defended themselves better in this action than in any battle I've seen."[101] Marlborough proceeded to take Mons on 20 October, but on his return to England his enemies used the Malplaquet casualty figures to sully his repute. Harley, now master of the Tory party, did all he could to persuade his colleagues that the Whigs – and by their apparent concord with Whig policy, Marlborough and Godolphin – were bent on leading the country to ruin, even hinting that the Duke was prolonging the war to line his own pockets.[102]

In March 1710, fresh peace talks re-opened between Louis and the Allies, but despite French concessions the Whig government remained unwilling to compromise. However, support for the pro-war policy of the Whigs was ebbing away and, by a series of successive steps, the whole character of the government was altered. Godolphin was forced from office and, after the general election in October, a new Tory ministry installed. Although Marlborough remained a national hero and a figure of immense European prestige, it took urgent entreaties from both Prince Eugene and Godolphin to prevent the Duke from proffering his resignation.[103]

Endgame

In January 1711, Marlborough – 'much thinner and greatly altered' – returned to England; the crowds cheered but the Queen's new ministers, Harley and Henry St John were less welcoming; if he wished to continue to serve, he was to be nothing more than their obedient military servant.[104] The Queen, who had recently expressed her intention of dismissing his wife, remained cold.[105] The Duke saw Anne in a last attempt to save his wife from dismissal, but she was not to be swayed by his supplicatory pleading, and demanded Sarah give up her Gold Key, the symbol of her office, within two days, warning – "I will talk of no other business till I have the key."[106]

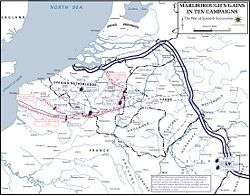

Notwithstanding all this turmoil – and his declining health – Marlborough returned to The Hague in March to prepare for what was to be his last campaign, and one of his greatest. Once again Marlborough and Villars formed against each other in line of battle, this time along the Avesnes-le Comte-Arras sector of the lines of Non Plus Ultra (see map).[107] Expecting another onslaught on the scale of Malplaquet, the allied generals surmised that their commander, distressed from domestic turmoil, was leading them to an appalling slaughter.[108] But by an exercise of brilliant psychological deception,[109] and a secretive night march covering 40 miles (64 km) in 18 hours, the Allies penetrated the allegedly impregnable lines without losing a single man; Marlborough was now in position to besiege the fortress of Bouchain.[110] Villars, deceived and outmanoeuvred, was helpless to intervene, compelling the fortress's unconditional surrender on 12 September. Historian David Chandler writes – "The pure military artistry with which he repeatedly deceived Villars during the first part of the campaign has few equals in the annals of military history … the subsequent siege of Bouchain with all its technical complexities, was an equally fine demonstration of martial superiority."[111]

For Marlborough though, time had run out. Throughout 1711 secret peace negotiations (to which Marlborough was not privy), had proceeded between London and Versailles. On 7 December 1711 (O.S), the Queen was able to announce, that – "notwithstanding those who delight in the arts of war" – a sneer towards Marlborough – "both time and place are appointed for opening the treaty of a general peace." The Duke of Marlborough's services as Captain-General would no longer be required.[112]

Dismissal

The British representative, Henry St John, had gained highly favourable terms but Marlborough, who was a close associate of George of Hanover, the heir to the throne, and still enjoyed the support of the King of Prussia and the Princes of the Grand Alliance, was wholeheartedly against a separate peace treaty between Britain and France. Harley and St John now determined once and for all to mastermind Marlborough's fall.[113]

On 20 January 1711 (O.S), the Commissioners of Public Accounts laid a report before the Commons accusing the Duke (and others), of turning public funds to his own profit. Marlborough was confronted with two irregularities: first, an assertion that over nine years he had illegally received more than £63,000 from the bread and transport contractors in the Netherlands; second, that the 2.5% he had received from the pay of foreign troops, totalling £280,000, was public money and 'ought to be accounted for'.[114] On 31 December (O.S), the Queen saw fit to dismiss Marlborough from all employments so – "that the matter might have impartial examination."[115] Marlborough, however, was able to refute the charges of embezzlement. Concerning the first allegation he could claim ancient precedent: contractors had always paid a yearly sum as a perquisite to the commander-in-chief in the Low Countries. For the second charge he could produce a warrant signed by the Queen in 1702 authorising him to make the deduction – which had always been customary in the Grand Alliance since the days of King William – and that all the money received was used for providing him with the means of creating an intelligence network;[116] a Secret service that had penetrated the court of King Louis.

Able speeches in the House were made on the Duke's behalf, but the Tories (whose campaign of discrediting the Duke had included the talents of the great satirist Jonathan Swift) were in the majority. When the vote was taken it was carried by 270 against 165.[117] The Queen ordered the Attorney-General to prepare a prosecution against Marlborough, but St John, acknowledging the flimsiness of the government's case, was compelled to halt the impeachment proceedings – Marlborough's successor, the Duke of Ormonde, had himself already been authorized to take the same 2.5% commission on the pay of foreign troops.[118]

Return to favour

Marlborough, later to be joined by Sarah, left faction-torn England for the Continent. Reasons for his exile remain speculative, but wherever they travelled they were welcomed and fêted by the people and courts of Europe, where he was not only respected as a great general, but also as a Prince of the Holy Roman Empire.[119] Churchill visited Mindelheim in late May 1713, receiving royal honours from his subjects. But the fate of the principality, and of Churchill's effective sovereignty, depended upon the ultimate peace treaty, and it was exchanged 1713 for Mellenburg. Marlborough bore the exile better than his wife who complained – "Tis much better to be dead than to live out of England;" but further tragedy struck the aging Duke when news arrived of the death of his beloved daughter Elizabeth, Countess of Bridgewater, from smallpox.[120]

On their return to Dover on 2 August 1714 (O.S) (21 months after departure), they learnt that Queen Anne had died only the day before. They left immediately for London, escorted by a 'train of coaches and a troop of militia with drums and trumpets'. With equal warmth the Elector of Hanover, now King George I, received Marlborough with the welcoming words – "My Lord Duke, I hope your troubles are now all over."[121]

Reappointed as Master-General of Ordnance as well as Captain-General, Marlborough became once more a person of great influence and respect at court. Together with the Hanoverian minister Count Bernsdorf, the Hanoverian diplomatist Baron von Bothmar, and Lord Townshend, Marlborough returned to the heart of government; but the Duke's health was fading fast. His central position was increasingly taken over by Robert Walpole and James Stanhope, so much so that during the 1715 Jacobite rising, he was only nominally in command, leaving it to the younger men to deal decisively with the crisis.[122]

On 28 May 1716, shortly after the death of his favourite daughter Anne, Countess of Sunderland, the Duke suffered a paralytic stroke at Holywell House. This was followed by another stroke in November, this time at a house on the Blenheim estate. The Duke recovered somewhat, but while his speech had become impaired, his mind remained clear, recovering enough to ride out to watch the builders at work on Blenheim Palace and its landscaped grounds.

In 1719 the Duke and Duchess were able to move into the east wing of the unfinished palace, but Marlborough had only three years to enjoy it. While living at the Great Lodge in Windsor Great Park, he suffered another stroke in June 1722, not long after his 72nd birthday. His two surviving daughters, Henrietta Godolphin and Mary Montagu, called on their dying father; but to Sarah, who had always felt the children an intrusion between herself and her husband, this was an unwelcome visitation. In the night hours the Duke began to slip away, and on the morning of 16 June 1722 (O.S), John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, died.

Assessment

Personal

To military historian David Chandler, Marlborough is without doubt the greatest British commander in history, an assessment that is shared by others, including the Duke of Wellington who could – "conceive nothing greater than Marlborough at the head of an English army." However, the Whig historian, Thomas Macaulay, denigrates Marlborough throughout the pages of his History of England; in the words of historian John Wilson Croker, Macaulay pursues the Duke with "more than the ferocity, and much less than the sagacity, of a bloodhound."[123] It was in response to Macaulay’s History that Winston Churchill (Marlborough’s descendant) wrote his four volume work, Marlborough: His Life and Times.

Marlborough was ruthlessly ambitious, relentless in the pursuit of wealth, power and social advancement. Indeed, in his quest for fame and personal interests he could be somewhat unscrupulous, as his desertion of King James testifies.[124] But this selfishness was also matched by a strong streak of altruism, witnessed by his loyalty to Queen Anne after the decline of their friendship until 1712, and his refusal to accept the twice-proffered position of Viceroy of the Spanish Netherlands in the interests of the Second Grand Alliance.[124] Indeed, it was this diplomatic tact that enabled Marlborough to hold together an often disparate alliance throughout the War of the Spanish Succession.

Although avaricious and exceptionally mean where money was concerned (a possible consequence of his early impoverishment at Ashe House), Marlborough was also known for his great charm and gentleness. He was not, however, above straightforward flattery, assuring King Charles XII of Sweden during his visit in 1707 of his desire to serve under his command, and to learn the last refinements of the military arts.[124] To his enemies, the Duke was courteous – his treatment of Marshal Tallard after Blenheim is one of many examples; but it was not just his social equals that Marlborough displayed compassion. His concern for the welfare of the common soldier (it was not entirely uncommon for the Duke to offer a tired trooper on campaign a lift in his personal coach), together with his ability to inspire trust and confidence, often earned him adulation from his men – "The known world could not produce a man of more humanity," observed Corporal Matthew Bishop.[125]

When occasion demanded it, however, he could be ruthless. The hard realities of early 18th century warfare offers no better example than the Duke’s ravaging of the Bavarian countryside prior to the Battle of Blenheim in 1704; for military ends, he was prepared to burn 400 villages in the name of ‘cruel necessity’.[125] But it was whilst on campaign that Marlborough shows us another virtue – his courage. Although frequently depressed and even physically unwell prior to a major engagement such as Blenheim or Oudenarde, his personal interventions at Ramillies and Elixheim for example, provide ample testimony to his continued gallantry – a reputation he had held since the siege of Maastricht in 1673.

Military

On the grand strategic level Marlborough had rare ability to grasp the broad issues, but he had to deal with doubting governments and hesitant Allies; he suffered greatly from obstructive Dutch field-deputies and generals, and frequently had to compromise in order to ensure co-operation.[126] As a strategist he preferred battle over slow moving siege warfare; even if the immediate cost – such as at the Schellenberg – was high. Aided by an expert staff (particularly his carefully-selected aides-de-camp such as Cadogan), as well as enjoying an excellent relationship with the talented Imperial commander, Prince Eugene, Marlborough proved far-sighted, often way ahead of his contemporaries in his conceptions, and was a master at assessing his enemy’s characteristics in battle.[127]

At the tactical level, Marlborough was again extremely adept. Invariably he would aim to seize the initiative, and commit to action whether the enemy desired it or not – at the Schellenberg for example, he achieved surprise by attacking late in the afternoon. Having thrown his foe off balance, the Duke would launch initial probing attacks to draw enemy reserves into action, whilst his own forces completed their own battle formations. This probing action would induce the enemy to weaken the sector chosen by the Captain-General for the main attack, and where he would assemble a decisive superiority of force to deliver the fatal blow.

Once victory was assured, Marlborough was unusual in his belief of immediate pursuit – after the battles of Schellenberg and Ramillies the follow-through was relentless.[128] But although Marlborough was more likely to manoeuvre than his opponents, and was better at maintaining operational tempo at critical times, the Duke qualifies more as a great practitioner within the constraints of early 18th century warfare, rather than as a great innovator who radically redefined military theory.[129] Additionally, his tactics – attack the enemy flanks and make a breakthrough at the centre – could become somewhat predictable. Nevertheless, his predilection for fire, movement, and co-ordinated all-arms attacks, lay at the root of his great battlefield successes.[130]

Marlborough’s administrative skills and attention to detail meant his troops rarely went short of bread, shoes, clothing, tents or billets – when his army arrived at its destination it was intact and in a fit state to fight.[131] Although he eschewed innovation, he had the aptitude to make existing systems of supply work well. It was this range of abilities that makes Marlborough outstanding.[131] Yet all this would have meant little without enormous reserves of stamina, willpower and self-discipline. As Winston Churchill declared: "He commanded the armies of Europe against France for ten campaigns. He fought four great battles and many important actions … He never fought a battle that he did not win, nor besieged a fortress that he did not take … He quitted war invincible."[132] No other British soldier has ever carried so great a weight and variety of responsibility.[131]

Notes

- ↑ All dates in the article are relating to Britain are Old Style (meaning Julian calendar with 1 January as the start of the year). Events on the Continent are given as New Style (meaning Gregorian calendar). Old Style dates were 10 days behind in the 17th century; from 1700 the difference became 11 days. Thus, the Battle of Blenheim is 13 August N.S or 2 August O.S.

- ↑ Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, p. 27. Churchill insists that the often recorded fine of £4446 18s was a misprint in Hutchin’s History of Dorset, 1774. This huge figure was subsequently, and erroneously repeated by other Marlborough biographers including Coxe.

- ↑ Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, p. 31

- ↑ Barnett: Marlborough, p. 60

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 5

- ↑ Arabella later became one of the Duke of York's mistresses.

- ↑ Coxe: Memoirs of the Duke of Marlborough, vol.i p. 2

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, p. 6

- ↑ Although details of this period are sketchy, it is surmised that in 1670 he also served aboard ship in the naval blockade of the Barbary pirate-den of Algiers.

- ↑ Hibbert The Marlboroughs, p. 7. Churchill was 20, she was 29 when they became lovers.

- ↑ Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, p. 60. The story may be apocryphal (another version has Churchill jumping out of the window), but it is widely accepted that Churchill was the father of Cleveland's last daughter born on July 16, 1672 (O.S).

- ↑ Barnett: Marlborough, p. 40

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs p. 9

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 7

- ↑ Macaulay: The History of England, p.82

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 8

- ↑ Gregg: Queen Anne

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, p. 13

- ↑ Field: The Favourite: Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, p. 8

- ↑ Field: The Favourite: Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, p. 23

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, p. 14

- ↑ Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, p. 129

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, p. 18

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Barnett: Marlborough, p. 43

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 10.

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, p. 24. During his time in Scotland, Churchill was dispatched on various important diplomatic missions. His personal successes led to talk of him becoming British minister at The Hague.

- ↑ Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, p. 164

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, p. 27

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, p. 28

- ↑ Barnett: Marlborough, p. 135

- ↑ Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, p.179

- ↑ Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, p. 188

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 22. Churchill played no part in the aftermath of slaughter.

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 21

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, p. 36

- ↑ Coxe: Memoirs of the Duke of Marlborough, vol. i, p. 18

- ↑ Coxe: Memoirs of the Duke of Marlborough, vol. i, p. 20

- ↑ Miller: James II, p. 187

- ↑ Churchill: Marlbrough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, p. 240

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, p. 41

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 24

- ↑ Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, p. 263

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, p. 46

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 25.

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, p. 48

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 35

- ↑ Barnett: Marlborough, p. 137: Anne wished to have her own Civil List income granted by Parliament, rather than a grant from the Privy Purse, which meant reliance on William. In this, and other matters, Anne was supported by Sarah.

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, p. 50

- ↑ Barnett: Marlborough, p. 22. Godert de Ginkell, remained in command in Ireland while Waldeck, who had been severely beaten by the duc de Luxembourg at Fleurus in July 1690, continued in charge of the allied army on the Continent.

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 46: William's Dutch friend,

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, p. 57

- ↑ Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, p. 327

- ↑ Churchill: A History of the English-Speaking Peoples: Age of Revolution, p. 11.

- ↑ Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, p. 341

- ↑ Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, p. 343

- ↑ Barnett: Marlborough, p. 137: Queen Mary also demanded Anne should dismiss Sarah, which she refused to do.

- ↑ Churchill: A History of the English-Speaking Peoples: Age of Revolution, p. 12: John Childs in his British Army of William III, p. 63, states that the most serious misdemeanour in the eyes of William was his "role in alienating the British army officer corps from the Dutch and German generals."

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 58.2 Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 47

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, p. 67

- ↑ Thomas Macaulay in his History of England suggests that Marlborough betrayed the allied plans to rid himself of a talented rival.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 48

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, p. 80. Marlborough's son John, was appointed Master of the Horse at a salary of £500 a year.

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 49

- ↑ Gregg: Queen Anne, p. 126: Marlborough was also to settle the number of soldiers and sailors each coalition partner was to contribute and to supervise the organisation and supply of these troops. In these matters he was ably assisted by Adam Cardonnel and William Cadogan.

- ↑ Barnett: Marlborough, p. 24

- ↑ Gregg: Queen Anne, p. 153: £4m in today's money.

- ↑ Barnett: Marlborough, p. 31

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 104. The Dutch generals and deputies were naturally concerned by the threat of an invasion from a powerful enemy.

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 107. The Queen also granted him £5,000 annually for life, but Parliament refused. Sarah, indignant at this ingratitude, suggested he refuse the title.

- ↑ Gregg: Queen Anne, p. 118. Marlborough himself was not keen on the marriage but Sarah, enchanted by his Whig ideology and intellectual prowess, was decidedly more enthusiastic.

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, p. 115

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 116. Boufflers redeemed himself with a crushing victory over the Dutch at the Battle of Eckeren.

- ↑ Gregg: Queen Anne, p. 172. A commemorative medal of these gains was cast with Queen Anne on one side and Marlborough on the other together with the inscription – 'Victory without slaughter.'

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, p. 119

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 121

- ↑ Barnett: Marlborough, p. 121

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667–1714, p. 286

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 128

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667–1714, p. 294

- ↑ Churchill: A History of the English-Speaking Peoples: Age of Revolution, p. 44

- ↑ Barnett: Marlborough, p. 192

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, p. 207. Anne was a Tory; Sarah was a committed Whig who considered most Tories little better than Jacobites.

- ↑ The Treaty of Utrecht restored Mindelheim to the Elector of Bavaria.

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 157

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 154

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 164. Marlborough, for once making no attempt to hide his feelings, complained to the States-General, resulting in General Slangenburg's dismissal.

- ↑ Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 2, p. 79. For months Marlborough had been preparing for that end: troops, money and equipment gathered for its eventuality.

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667–1714, p. 308

- ↑ Gregg: Queen Anne, p. 216

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 186. Sunderland was Marlborough's son-in-law; he had married his daughter Anne.

- ↑ Barnet: Marlborough, p. 195. Abigail was Sarah's cousin and had been recommended by her for a minor court position.

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 199

- ↑ Barnet: Marlborough, p. 197

- ↑ Churchill: A History of the English-Speaking Peoples: Age of Revolution, p. 59

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 222. One French commentator said the battle – "reduced us … to a timid and difficult defensive … we were effectively under the orders of M. de Marlborough."

- ↑ Barnett: Marlborough, p. 212

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, p. 232

- ↑ Barnett: Marlborough, p. 214

- ↑ Gregg: Queen Anne, p. 279

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 Barnett: Marlborough, p. 235

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 266

- ↑ Barnett: Marlborough, p. 229

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 281

- ↑ Barnett: Marlborough, p. 256

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, p. 267. The loss of his wife's offices would also be a severe blow to his own prestige.

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, p. 268

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667–1714, p. 79. The Non Plus Ultra lines were the last and most imposing entrenched fortifications designed to halt enemy raids and hinder the movements of enemy armies. The Non Plus Ultra lines ran from the coast at Montreuil to the River Sambre.

- ↑ Churchill: A History of the English-Speaking Peoples: Age of Revolution, p. 73

- ↑ Barnett: Marlborough, p. 259

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667–1714, p. 343

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 299

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, p. 278

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 302

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 302. The Tory Examiner, for which the poet Matthew Prior and author Jonathon Swift wrote, also accused the Duke of diverting money from the medical services to line his own pockets.

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, p. 286

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 302. Marlborough employed an extensive network of spies, informers and reporters who kept him supplied with intelligence.

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, p. 285

- ↑ Barnett: Marlborough, p. 267

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, p. 290. Mindelheim was lost 1714 to the Elector of Bavaria under Treaty of Utrecht, without compensation. Marlborough lost the principality of Mindelheim at the Treaty of Rastadt, but retained the title which was passed on to future Dukes of Marlborough.

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, p. 295. It is said on hearing the news, his head dropped with such force on the marble mantelpiece that he fell unconscious to the floor.

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, p. 298

- ↑ Hibbert: The Marlboroughs, p. 300

- ↑ Macaulay: The History of England, p. 32

- ↑ 124.0 124.1 124.2 Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 313

- ↑ 125.0 125.1 Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 314

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 323

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 324

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 325

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667–1714, p. 273

- ↑ Chandler: Marlborough as Military Commander, p. 327

- ↑ 131.0 131.1 131.2 Barnett: Marlborough, p. 264

- ↑ Churchill: Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, p. 15

References

- Barnett, Correlli. Marlborough. Wordsworth Editions Limited, (1999). ISBN 1-84022-200-X

- Chandler, David G. Marlborough as Military Commander. Spellmount Ltd, (2003). ISBN 1-86227-195-X

- Churchill, Winston. A History of the English-Speaking Peoples: Age of Revolution. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, (2002). ISBN 0-304-36393-6

- Churchill, Winston. Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 1, vols. i & ii. University of Chicago Press, (2002). ISBN 0-226-10633-0

- Churchill, Winston. Marlborough: His Life and Times, Bk. 2, vols. iii & iv. University of Chicago Press, (2002). ISBN 0-226-10635-7

- Coxe, William. Memoirs of the Duke of Marlborough: 3 volumes. London, (1847)

- Field, Ophelia. The Favourite: Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough. Hodder and Stoughton, (2002). ISBN 0-340-76807-X

- Gregg, Edward. Queen Anne. Yale University Press, (2001). ISBN 0-300-09024-2

- Hibbert, Christopher. The Marlboroughs. Penguin Books Ltd, (2001). ISBN 0-670-88677-7

- Lynn, John A. The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667–1714. Longman, (1999). ISBN 0-582-05629-2

- Macaulay, Thomas. The History of England (abridged). Penguin Books, (1968). ISBN 0-14-043-133-0

- Miller, John. James II. Yale University Press, (2000). ISBN 0-300-08728-4

| Legal offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Sir Harbottle Grimston |

Master of the Rolls 1685 |

Succeeded by Sir John Trevor |

| Military offices | ||

| Preceded by The Earl of Feversham |

Captain and Colonel of the 3rd Troop of Horse Guards 1685–1688 |

Succeeded by The Duke of Berwick |

| Preceded by The Duke of Berwick |

Captain and Colonel of the 3rd Troop of Horse Guards 1689–1692 |

Succeeded by Viscount Colchester |

| Preceded by The Earl of Feversham |

Commander-in-Chief of the Forces 1690–1691 |

Succeeded by The Duke of Leinster |

| Vacant | Captain-General 1702–1711 |

Succeeded by The Duke of Ormonde |

| Preceded by The Earl of Romney |

Master-General of the Ordnance 1702–1712 |

Succeeded by The Earl Rivers |

| Vacant | Commander-in-Chief of the Forces 1702–1708 |

Vacant |

| Preceded by The Duke of Ormonde |

Captain-General 1714–1717 |

Vacant |

| Vacant

Title last held by

The Duke of Hamilton |

Master-General of the Ordnance 1714–1722 |

Succeeded by The Earl Cadogan |

| Honorary titles | ||

| Preceded by The Earl of Abingdon |

Lord Lieutenant of Oxfordshire 1706–1712 |

Succeeded by The Earl of Abingdon |

| Peerage of England | ||

| New creation | Duke of Marlborough 1702–1722 |

Succeeded by Henrietta Godolphin |

| Earl of Marlborough 1689–1722 |

||

| Baron Churchill of Sandridge 1685–1722 |

||

| Peerage of Scotland | ||

| New creation | Lord Churchill of Eyemouth 1682–1722 |

Extinct |

| German nobility | ||

| Preceded by Maximilian II Emanuel, Elector of Bavaria |

Prince of Mindelheim 1705–1714 |

Succeeded by Maximilian II Emanuel, Elector of Bavaria |

|

|||||||

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Churchill, John |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | 1st Duke of Marlborough |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 26 May, 1650 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Ashe House, Devon |

| DATE OF DEATH | 27 June, 1722 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Windsor Lodge |