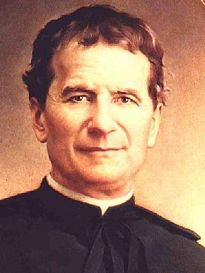

John Bosco

| Don John Bosco | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Confessor; Father and Teacher of Youth | |

| Born | August 16, 1815, Castelnuovo, Piedmont, Italy |

| Died | January 31, 1888 (aged 72), |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church, Anglican Communion |

| Beatified | June 2, 1929, Rome by Pope Pius XI |

| Canonized | April 1, 1934, Rome by Pope Pius XI |

| Major shrine | The Tomb of St John Bosco, Basilica of Our Lady Help of Christians, Turin, Italy |

| Feast | January 31 |

| Patronage | Christian apprentices, editors, publishers, schoolchildren, young people |

Saint John Bosco (born Giovanni Melchiorre Bosco, known in English as Don Bosco; August 16 1815 – January 31 1888), was an Italian Catholic priest, and recognized educator, who put into practice the dogma of his religion, employing teaching methods based on love rather than punishment. He placed his works under the protection of Francis de Sales; thus his followers styled themselves the Salesian Society. He is the only Saint with the title "Father and Teacher of Youth."

St John Bosco succeeded in establishing a network of centres to carry on his work. In recognition of his work with disadvantaged youth he was canonized by Pope Pius XI in 1934. One of his students, Dominic Savio, was subsequently also canonized, becoming the youngest non-martyr to be named a saint.

Contents |

Early life

John Bosco was born in Becchi, a frazione of Castelnuovo d'Asti[1], in Piedmont (then part of the Kingdom of Sardinia), to Francesco Bosco and his second wife Margherita Occhiena of Capriglio. His father died two years later and Giovanni, together with his two brothers Antonio and Giuseppe, were brought up by his mother. She was to support him in his work until her death in 1856. His mother loved him dearly.

When he was young, he would put on shows of his skills as a juggler, magician, and acrobat. The price of admission to these shows was a prayer.[2] Don Bosco began as the chaplain of the Rifugio ("Refuge"), a girls’ boarding school founded in Turin by the Marchioness Giulia di Barolo. But he had many ministries on the side such as visiting prisoners, teaching catechism and helping out at country parishes. A growing group of boys would come to the Rifugio on Sundays and feast days to play and learn their catechism. They were too old to join the younger children in regular catechism classes in the parishes, which mostly chased them away. This was the beginning of the “Oratory of St. Francis de Sales”. Because of all their disorderly racket, the Marchioness spared her girls the distraction by terminating Bosco’s employment at the Rifugio.

Don Bosco and his Oratory wandered around town for a few years and were turned out of several places in succession. Finally, he was able to rent a shed from a Mr. Pinardi. His mother moved in with him. The Oratory had a home, then, in 1846, in the new Valdocco neighborhood on the north end of town. The next year, he and "Mamma Margherita" began taking in orphans.

Even before this, however, Don Bosco had the help of several friends at the Oratory. There were zealous priests like Don Cafasso and Don Borel, some older boys like Giuseppe Buzzetti, Michael Rua, Giovanni Cagliero, and Carlo Gastini, and Don Bosco’s own mother, Mama Margaret, as she was affectionatly known. Some local politicians helped out while others hindered his efforts.

One friend was Justice Minister Urbano Rattazzi, who did not support the church, but nevertheless recognized the value of Don Bosco’s work. While Rattazzi was pushing a bill through the Sardinian legislature to suppress religious orders, he advised Don Bosco on how to get around the law and found a religious order to keep the Oratory going after its founder’s death. Bosco had been thinking about that problem, too, and had been slowly organizing his helpers into a loose “Congregation of St. Francis de Sales”. He was also training select older boys for the priesthood on the side. Another supporter of the religious order idea was the reigning Pope, Blessed Pius IX. In 1854, when the Kingdom of Sardinia was about to pass a law suppressing monastic orders and confiscating ecclesiastical properties, Bosco reported a series of dreams about "great funerals at court," referring to members of the Savoy court or of politicians.[3] In November 1854, he sent a letter to the King, Victor Emmanuel II, admonishing him to oppose the confiscation of Church property and suppression of the orders, but the King did nothing.[4] His activity, which had been described by one critic, Italian historian Erberto Petoia, as having "manifest blackmailing intentions",[5] according to Petoia ended only after the intervention of Prime Minister Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour. Despite such criticisms, the King's family suffered a surprising number of deaths in a short period; from January to May 1855, the King's mother age 55, wife, 33, newborn son, and his only brother, 33, all died. [6][7]

In 1859, Bosco selected the experienced priest Don Alasonatti, 15 seminarians and 1 high school boy and formed them into the "Society of St. Francis de Sales." This was the nucleus of the Salesians, the religious order that would carry on his work. When the group had their next meeting, they voted on the admission of Joseph Rossi as a lay member, the first Salesian brother. The Salesian Congregation was divided into priests, seminarians and "coadjutors" (the lay brothers).

Next, he worked with Don Pestarino, Mary Mazzarello and a group of girls in the hill town of Mornese. In 1871, he founded a group of religious sisters to do for girls what the Salesians were doing for boys. They were called the "Daughters of Mary Help of Christians." In 1874, he founded yet another group: the "Salesian Cooperators." These were mostly lay people who would work for young people like the Daughters and the Salesians, but would not join a religious order.[8]

The story of the departure of the first Salesians for America in 1875 is based on the missionary ideal of Don Bosco. All his life he wanted to be a missionary, and his biographer mentions that he was already thinking about it when he was a young student at Chieri. After his ordination, he would have become a missionary had not his director, Joseph Cafasso, opposed the idea. He eagerly read the Italian edition of the Annals of the Propagation of the Faith and used this magazine to illustrate his Cattolico provveduto (1853) and his Month of May booklets (1858).

When he founded the Salesian Society, the thought of the missions still obsessed him, and he would gladly have sent his religious had he not then completely lacked the means. Father Lemoyne states that Don Bosco had to be satisfied for a long time to just ardently study the map of the world or to speak to the Oratory boys about the labors of missionaries, or the martyrdom suffered by some of them, or about the people they converted to the Gospel.

Around 1871-72 one of his "dreams" encouraged him. He found himself transported to a vast plain, inhabited by primitive peoples, who spent their time hunting or fighting among themselves or against soldiers in European uniforms. Along came a band of missionaries, but they were all horribly massacred. A second group appeared with an air of joy about them; they were preceded by a group of children. Don Bosco at once recognized them as Salesians. Astonished, he witnessed an unexpected change when the fierce savages laid down their arms and listened to the missionaries. The dream made a great impression on Don Bosco, because he tried hard to identify the men and the country of the dream.

It is said that he searched for three years among documents, trying to get information about different countries. For a moment he thought it might be Abyssinia, then Hong Kong, then Australia, then India. One day, however, a request came from the republic of Argentina, which turned him towards the Indians of Patagonia. To his surprise, a study of the people there convinced him that the country and its inhabitants were the ones he had seen in his dream.

He regarded it as a sign of Providence and set about the realization of a project long dear to him. Adopting a special way of evangelization that would not expose his missionaries suddenly to wild, uncivilized tribes, he proposed to set up bases in safe locations where their missionary efforts were to be launched. The above request from Argentina came about as follows: Towards the end of 1874, he received letters from that country requesting that he accept an Italian parish in Buenos Aires and a school for boys at San Nicolas de los Arroyos. Gazzolo, the Argentine Consul at Savona, had sent the request, for he had taken a great interest in the Salesian work in Liguria and hoped to obtain the Salesians' help for the benefit of his country. Negotiations started after Archbishop Aneiros of Buenos Aires had indicated that he would be glad to receive the Salesians. They were successful mainly because of the good offices of the priest of San Nicolas, Pedro Ceccarelli, a friend of Gazzolo, who was in touch with and had the confidence of Don Bosco. In a ceremony held on January 29, 1875, Don Bosco was able to convey the great news to the Oratory in the presence of Gazzolo. On February 5, he announced the fact in a circular letter to all Salesians asking volunteers to apply in writing. He proposed that the first missionary departure start in October. Practically all the Salesians volunteered for the missions. Certainly a new era had now begun for the Oratory and the young Society.

By this time Italy was united, with borders similar to those of today, under Piedmontese leadership. The poorly-governed Papal States were merged into the new kingdom. It was generally thought that Don Bosco supported the Pope.

He was a great saint.

The Preventive System

Don Bosco's capability to attract numerous boys and adult helpers was connected to his "Preventive System of Education". He believed education to be a "matter of the heart," and said that the boys must not only be loved, but know that they are loved. He also pointed to three components of the Preventive System: reason, religion, and kindness. Music and games also went into the mix.

Don Bosco gained a reputation early on of being a saint and miracle worker. For this reason Rua, Buzzetti, Cagliero and several others began to keep chronicles of his sayings and doings. Preserved in the Salesian archives, these are invaluable resources for studying his life. Later on, the Salesian Don Lemoyne collected and combined them into 77 scrapbooks with oral testimonies and Don Bosco’s own Memoirs of the Oratory. His aim was to write a detailed biography. This project eventually became a nineteen-volume affair, carried out by him and two other authors. These are the Biographical Memoirs. It is clearly not the work of professional historians, but a somewhat uneven compilation of those chronicles that preserve the memories of teenage boys and young men under the spell of a remarkable and beloved father figure.

Death and canonization

Don Bosco died on January 31, 1888. His funeral was attended by thousands, and very soon after there were popular demands to have him canonized. Accordingly, the Archdiocese of Turin began to investigate and witnesses were called to determine if his holiness were worthy of a declared Saint. As expected, the Salesians, Daughters and Cooperators gave fulsome testimonies. But many remembered Don Bosco’s controversies in the 1870s with Archbishop Gastaldi, and some others high in the Church hierarchy thought him a loose cannon and a wheeler-dealer. In the canonization process, testimony was heard about how he went around Gastaldi to get some of his men ordained, and about their lack of academic preparation and ecclesiastical decorum. Political cartoons from the 1860s and later showed him shaking money from the pockets of old ladies, or going off to America for the same purpose, and were not forgotten. These opponents, including some cardinals, were in a position to block his canonization and many Salesians feared around 1925 that they would succeed.

Pope Pius XI had known Don Bosco, and pushed the cause forward. Bosco was declared Blessed in 1929, and canonized on Easter Sunday of 1934 and was given the title of "Father and Teacher of Youth." [9]

Fr. Silvio Mantelli, SDB, had petitioned Pope John Paul II to acclaim St John Bosco the Patron of Stage Magicians. Catholic stage magicians who practice Gospel Magic venerate Don Bosco by offering free magic shows to underprivileged children on his feast day.

Don Bosco's work was carried on by his constant companion, Don Michael Rua, who was appointed Rector Major of the Salesian Society by Pope Leo XIII in 1888.

Further reading

Dream of the Great Ship - Interpretations of Saint John Bosco's Dream of the Two Columns

Sources

- Bosco, Giovanni (1989). Memoirs of the Oratory. Don Bosco Publications.

- Amadei, Angelo; Giovanni Battista Lemoyne, Eugenio Ceria. Biographical Memoirs of St. John Bosco. Don Bosco Publications.. These volumes translate id.. Memorie Biografiche di San Giovanni Bosco, 19 vol.. SEI.

Studies

- Desramaut, François (1996). Don Bosco et son Temps. SEI.

- Stella, Pietro (1996). Don Bosco: Religious Outlook and Spirituality. Salesiana Publishers.

- Wirth, Morand (1982). Don Bosco and the Salesians. New Rochelle, New Jersey. Don Bosco Publications. Translation of id. (1969). Don Bosco e i Salesiani: Centocinquant'anni di storia. SEI.

See also

- Salesians

- Dominic Savio

- St. Don Bosco's College

- St John Bosco College

External links

- Salesians of Don Bosco Official Website (multi-lingual website)

- Salesians of the UK

- UK Salesian (alumnus) website

- Don Bosco's important writings in original language

- Founder Statue in St Peter's Basilica

- Published Writings (italian)

References

- ↑ Later rechristened Castelnuovo Don Bosco in his honour.

- ↑ http://www.magnificat.ca/cal/engl/01-31.htm

- ↑ Mendl, Michael The Dreams of St. John BoscoJournal of Salesian Studies 12 (2004), no. 2, pp. 321-348.

- ↑ Memoirs of the Oratory of Saint Francis de Sales 1815 - 1855: THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF SAINT JOHN BOSCO Translated by Daniel Lyons, SDB, with notes and commentary by Eugene Ceria SDB, Lawrence Castelvecchi SDB, and Michael Mendl SDB, Ch. 55, fn. 802

- ↑ Petoia, Erberto (June 2007). "I sinistri presagi di Don Giovanni Bosco". Medioevo: p. 70.

- ↑ Mendl, Michael The Dreams of St. John BoscoJournal of Salesian Studies 12 (2004), no. 2, pp. 321-348.

- ↑ Memoirs of the Oratory of Saint Francis de Sales 1815 - 1855: THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF SAINT JOHN BOSCO Translated by Daniel Lyons, SDB, with notes and commentary by Eugene Ceria SDB, Lawrence Castelvecchi SDB, and Michael Mendl SDB, Ch. 55, fn. 802

- ↑ "Patron Saints Index". Retrieved on 2007-10-18.

- ↑ "Catholic Online". Retrieved on 2007-10-18.