Johann Strauss II

Johann Strauss II (October 25, 1825 – June 3, 1899; German: Johann Sebastian Strauß; also known as Johann Sebastian Strauss, Johann Strauss, Jr., or Johann Strauss the Younger) was an Austrian composer famous for having written over 500 waltzes, polkas, marches, and galops. He was the son of the composer Johann Strauss I, and brother of composers Josef Strauss and Eduard Strauss. He is also the most famous member of the Strauss family. He was known in his lifetime as "The Waltz King", and was largely responsible for the popularity of the waltz in Vienna during the 19th century. He revolutionized the waltz, elevating it from a lowly peasant dance to entertainment fit for the royal Habsburg court. His works enjoyed greater fame than his predecessors, such as Johann Strauss I and Josef Lanner. Some of Strauss' most famous works include The Blue Danube, Wein, Weib und Gesang, Tales from the Vienna Woods, Tritsch-Tratsch-Polka, the Kaiser-Walzer, and the operetta Die Fledermaus.

Contents |

Biography

The early years

Strauss was born in Vienna, Austria, on 25 October 1825, to the famous composer Johann Strauss I. His father did not want him to become a musician but rather a banker;[1] nevertheless, Strauss Junior studied the violin secretly as a child, ironically with the first violinist of his father's orchestra, Franz Amon.[1] When his father discovered this, Johann the younger recalled that "there was a violent and unpleasant scene" and that "his father wanted to know nothing of his musical plans." It seems that rather than trying to avoid a Strauss rivalry, the elder Strauss only wanted his son to escape the rigors of a musician's life. It was only when his father left the family and took a mistress, Emilie Trampusch, when the son was 17, that he was able to concentrate fully on a career as a composer with the support of his mother.

Strauss II studied counterpoint and harmony with theorist Professor Joachim Hoffmann,[1] who owned a private music school. His talents were also recognized by composer Josef Drechsler, who taught him exercises in harmony. His other violin teacher, Anton Kollmann, who was the ballet répétiteur of the Vienna Court Opera, also wrote excellent testimonials for him. Armed with these, on the very same day his mother filed a divorce from her husband, he approached the Viennese authorities to apply for a license to perform.[2] He initially formed his small orchestra where he recruited his members at the 'Zur Stadt Belgrad' tavern, where musicians seeking work could be hired easily.

Johann Strauss I's influence over the local entertainment establishments meant that many of them were wary of offering the younger Strauss a contract for fear of angering the father.[2] Strauss Jr. was able to persuade the Dommayer's Casino in Hietzing (a suburb of Vienna) to allow him to perform.[3] As a result, the local press was soon frantically reporting a 'Strauss v. Strauss' rivalry between the father and the son. The elder Strauss, in anger at his son's disobedience, and at that of the proprietor, refused to ever play at the Dommayer's Casino again, which had been the site of many of his earlier triumphs.

Strauss II found the early years difficult, but he soon won over music-loving audiences after accepting commissions to perform away from home. The first major appointment for the young composer was his award of the honorary position of "Kapellmeister of the 2nd Vienna Citizen's Regiment", which had been left vacant following Josef Lanner's death two years before. Vienna was racked by a bourgeois revolution on February 24, 1848, and the intense rivalry between father and son became much more apparent.

Eventually, Johann Jr. decided to side with the revolutionaries, as evidenced in the title of his works dating around this period, such as the waltzes 'Freiheitslieder' (Songs of Freedom) op. 52 and 'Burschenlieder' op. 55, and the marches 'Revolutions March', op. 54 and the stirring Studenten Marsch op. 56. It proved to be a decision which was professionally disadvantageous, as the Austrian royalty twice denied him the much coveted 'KK Hofballmusikdirektor' position, which was first designated especially for Johann I in recognition of his musical contributions. Further, the younger Strauss was also arrested by the Viennese authorities for publicly playing the infectious La Marseillaise, which stoked revolutionary feelings, but he was later acquitted.[4] Shortly after that, he composed the 'Geißelhiebe Polka', op. 60, which contains elements of 'La Marseillaise' in its 'Trio' section as a musical riposte to his arrest. The elder Strauss remained loyal to the Danube monarchy, and composed his Radetzky March op. 228 (dedicated to the Habsburg field marshal Joseph Radetzky von Radetz), which would become one of his best-known compositions.

When the elder Strauss died from scarlet fever in Vienna in 1849, the younger Strauss merged both their orchestras and engaged in further tours. Subsequently, he also composed a number of patriotic marches dedicated to the Habsburg monarch Franz Josef I, such as the 'Kaiser Franz-Josef Marsch' op. 67 and the 'Kaiser Franz Josef Rettungs Jubel-Marsch' op. 126, probably to ingratiate himself in the eyes of the new monarch, who ascended to the Austrian throne after the 1848 revolution.

Career advancements

Strauss Jr. would eventually surpass his father's fame, and become one of the most popular of waltz composers of the era, extensively touring Austria, Poland, and Germany with his orchestra. It would be a usual sight for his audiences to catch sight of Strauss for only one performance before he would quickly hurry to another venue, where he was commissioned to play via the traditional fiaker. It would be the ultimate showmanship and would be displayed on the placards at the venues to proudly proclaim 'Heute Spielt der Strauss!', or 'Strauss plays today!'.

Strauss also made visits to Russia, where he performed at Pavlovsk and wrote many compositions (such as the waltz "Farewell to Saint Petersburg", Op. 210), Britain, where he performed with his first wife Hetty Treffz at the Covent Garden, France, and Italy. Later in the 1870s, he took his orchestra to the United States, where he took part in the Boston Festival at the invitation of the bandmaster Patrick Gilmore and was the lead conductor in the 'Monster Concert' of over 1000 musicians,[5] performing his 'Blue Danube' waltz, amongst other pieces, to great acclaim.

Among the more popular dance pieces Strauss wrote in this period include the waltzes Sängerfahrten op. 41, Liebeslieder op. 114, Nachtfalter op. 157, Accelerationen op. 234, and the polkas Annen op. 117, and Tritsch-Tratsch-Polka op. 214.

Marriages

Strauss married the singer Jetty Treffz in 1862,[6] and applied for the KK Hofballmusikdirektor Music Director of the Royal Court Balls position, which he eventually attained in 1863, after being denied several times before for his frequent brush with the local authorities. His involvement with the Court Balls meant that his work has been elevated to be heard by the royalty. His second wife, Angelika Dittrich (an actress), whom he married in 1878, was not a fervent supporter of his music, and their differences in age and opinion, especially her indiscretion, led him to seek a divorce.[1]

Strauss was not granted a divorce by the Roman Catholic church, and therefore changed religion and nationality, and became a citizen of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha in January 1887.[1] Strauss II sought solace in his third wife Adele, whom he married in August 1882, and she encouraged the creative talent to flow once more in his later years, resulting in much fine music such as those found in the operettas Der Zigeunerbaron and Waldmeister, and the waltzes Kaiser-Walzer op. 437, Kaiser Jubiläum op. 434, and Klug Gretelein op. 462.

Adele, like Strauss' grandfather, was Jewish, a fact which the Nazis concealed.[7]

Family musical business

After establishing his first orchestra prior to his father's death, Strauss founded many others to be supplied to various entertainment establishments such as the 'Sperl' ballroom, as well as the 'Apollo', where he dedicated appropriately titled pieces to commemorate the first performances there. Later, he accepted commissions to play in Russia for the Archduke Michael and Tsar Alexander II, especially in Pavlovsk, where a new railway line was built. When the commissions became too much to be handled by him alone, he sought to promote his younger brothers Josef and Eduard to deputise in his absence from either poor health or a busy schedule. In 1853, Strauss was even confined to a sanatorium to recuperate as he was suffering from shivering fits and neuralgia. Anxious that the family business that she so lovingly nurtured would be ruined, mother Anna Strauss helped persuade a reluctant Josef to take over the helm of the Strauss Orchestra. The Viennese welcomed both brothers eventually and Johann even once admitted that 'Josef was the more talented of the two of us, I'm merely the more popular.' Josef went on to stamp his own mark into his waltzes, and this fresh rivalry did more good for the development of the waltz, as Johann proceeded to consolidate his position as the "waltz king" with his exquisite The Blue Danube waltz.

The highlight of the Strauss triumvirate was displayed in the concert of 'Perpetual Music' in 1860s, where his aptly titled "Perpetuum Mobile" musical joke was played continuously by all three Strauss brothers at the helm of three large orchestras. At around the same time, the three Strauss brothers also organised many musical activities during their concerts at the Vienna Volksgarten, where the audience would be able to participate. For example, a new piece would be played and the audience would be asked to guess who the composer was as the placards would only announce the piece as written by a 'Strauss' followed by question marks.

Musical rivals and admirers

Although Johann Strauss was the most sought-after composer of dance music in the latter half of the 19th century, stiff competition was present in the form of Karl Michael Ziehrer and Emile Waldteufel; the latter held a commanding position in Paris. Phillip Fahrbach also denied the younger Strauss the commanding position of the 'KK Hofballmusikdirektor' when the latter first applied for the post. The German operetta composer Jacques Offenbach, who made his name in Paris, also posed a challenge to Strauss in the operetta field. Later, the emergence of operetta maestro Franz Lehár would usher in the Silver Age in Vienna and most certainly sweep aside any lingering Strauss dominance in the operetta world.

Strauss was admired by other prominent composers: Richard Wagner once admitted that he loved the waltz Wein, Weib und Gesang op. 333. Richard Strauss (unrelated to the Strauss family), when writing his Rosenkavalier waltzes, said in reference to Johann Strauss the younger: "How could I forget the laughing genius of Vienna?"[8]

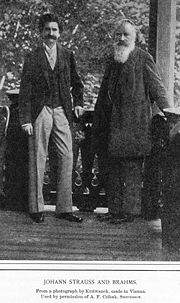

Johannes Brahms was a personal friend of Strauss, and to whom the latter dedicated his waltz "Seid umschlungen, Millionen!" ("Be Embraced, You Millions!"), op. 443. A story is told in biographies of both men that Strauss's daughter approached Brahms with a customary request that he autograph her fan. It was usual for the composer to inscribe a few measures of his best-known music, and then sign his name. Brahms, however, inscribed a few measures from the Blue Danube, and then wrote beneath it: "Unfortunately, NOT by Johannes Brahms."[9]

Stage works

Strauss' operettas have not had as much enduring success as have his dance pieces. Much of the success was reserved for Die Fledermaus, Eine Nacht in Venedig, and Der Zigeunerbaron. Notwithstanding the lack of popularity of his operettas, there are many dance pieces drawn from themes of his lukewarmly-received operettas such, as "Cagliostro-Walzer" op. 370 (Cagliostro in Wien), "O Schöner Mai" Walzer op. 375 (Prinz Methusalem), "Rosen aus dem Süden" Walzer op. 388 (Das Spitzentuch der Königin), and "Kuss-Walzer" op. 400 (Der Lustige Krieg). He also wrote an opera, Ritter Pásmán, which could be faulted on the libretto but nevertheless, many attribute his strong links to the waltz and the polka as his failure as this may well indicate that he may not be able to write serious music. In fact, for his third and most successful operetta of all time, Die Fledermaus, music critics of Vienna prophesied that his work would only be a 'motif of waltz and polka melodies'. Nonetheless, his fiercest critic, (and ironically a strong supporter) Eduard Hanslick, wrote at the time of Strauss's death in 1899 that his demise would signify the end of the last happy times in Vienna.

Death and legacy

Strauss was diagnosed with pneumonia in the spring of 1899,[10] and died on June 3, 1899, at the age of 73. He was buried in the Zentralfriedhof. At the time of his death, he was still composing his ballet Aschenbrödel.

Strauss' music is now regularly performed at the annual Neujahrskonzert of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, as a result of the efforts by Clemens Krauss who performed a special all-Strauss programme in 1929 with the Viennese orchestra. Many distinguished Strauss interpreters include Willi Boskovsky, who carried on the "Vorgeiger" tradition of conducting with violin in hand, as is the Strauss family custom, as well as Herbert von Karajan and the opera conductor Riccardo Muti. In addition, the Wiener Johann Strauss Orchester, which was formed in 1966, pays tribute to the touring orchestras of which the Strauss family are also known for.

It is to be noted that most of the Strauss works that we are all familiar with today may have existed in a barely different form as conceived by Johann Strauss, as Eduard Strauss destroyed a great amount of original Strauss orchestral archives in a furnace factory in Vienna's Mariahilf district in 1907.[11] The Johann Strauss societies around the world have, however, painstakingly pieced together a large body of these destroyed works to be appreciated by future generations. Eduard Strauss, then the only surviving brother, took this drastic precaution to prevent Strauss works from being openly claimed as another composer's own. This may have also been fuelled by the intense rivalry with the other popular waltz and march composer, Karl Michael Ziehrer.

Works of Johann Strauss II

Operetta

- Indigo und die vierzig Räuber Indigo and the Forty Thieves (1871)

- Der Karneval in Rom The Carnival in Rome (1873)

- Die Fledermaus The Bat (1874)

- Cagliostro in Wien Cagliostro in Vienna (1875)

- Prinz Methusalem Prince Methusalem (1877)

- Blindekuh Blind Man's Buff (1878)

- Das Spitzentuch der Königin The Queen's Lace Handkerchief (1880)

- Der lustige Krieg The Merry War (1881)

- Eine Nacht in Venedig A Night in Venice (1883)

- Der Zigeunerbaron The Gypsy Baron (1885)

- Simplicius (1887)

- Fürstin Ninetta Princess Ninetta (1893)

- Jabuka — Das Apfelfest Apple festival (1894)

- Waldmeister Woodruff (1895)

- Die Göttin der Vernunft The Goddess of Reason (1897)

- Wiener Blut (1899)

- Casanova (premiered in 1928, music arranged by Ralph Benatzky)

Opera

- Ritter Pásmán Knight Pásmán (1892)

Ballet

- Aschenbrödel Cinderella (1899)

Waltz

- Sinngedichte op. 1 Epigrams (1844)

- Gunstwerber op. 4 Favour Solicitor (1844)

- Faschingslieder op. 11 Carnival Songs (1846)

- Jugendträume op. 12 Youthful Dreams (1846)

- Sträußchen op. 15 Bouquets (1846)

- Sängerfahrten op. 41 Singers' Journeys (1847)

- Klange aus der Walachei op. 50 Echoes from Walachia (1850)

- Freiheitslieder op. 52

- Burschenlieder op. 55

- Frohsinns-Spenden op. 73 Gifts of Cheerfulness (1850)

- Lava-Ströme op. 74 Streams of Lava (1850)

- Rhadamantus-Klänge op. 94 Echoes of Rhadamantus (1851)

- Idyllen op. 95 Idylls (1851)

- Mephistos Höllenrufe op. 101 Cries of Mephistopheles from Hell (1851)

- Liebeslieder op. 114 Lovesongs (1852)

- Phönix-Schwingen op. 125 Wings of the Phoenix (1853)

- Schneeglöckchen op. 143 Snowdrops (1854)

- Novellen op. 146 Legal Amendments (1854)

- Nachtfalter op. 157 Moths (1855)

- Glossen op. 163 Marginal Notes (1855)

- Man lebt nur einmal! op. 167 You Only Live Once! (1855)

- Abschieds-Rufe op. 179 Cries of Farewell (1856)

- Grossfürsten Alexandra-Walzer op.181 Grand Duchess Alexandra (1856)

- Phanomene op. 193 Phenomena (1857)

- Abschied von St. Petersburg op. 210 Farewell to Saint Petersburg (1858)

- Hell und Voll op. 216 Bright and Full (1859)

- Promotionen op. 221 Graduations (1859)

- Accelerationen op. 234 Accelerations (1860)

- Immer heiterer op. 235 More and More Cheerful (1860)

- Grillenbanner op. 247 Banisher of Gloom (1861)

- Klangfiguren op. 251 (1861)

- Dividenden op. 252 Dividends

- Patronessen op. 264 Patronesses (1862)

- Karnevalsbotschafter op. 270 Carnival Ambassador (1862)

- Leitartikel op. 273 Leading Article (1863)

- Morgenblätter op. 279 Morning Journals (1863)

- Studentenlust op. 285 Students' Joy (1864)

- Aus den Bergen op. 292 From the Mountains (1864)

- Feuilleton op. 293 (1865)

- Bürgersinn op. 295 Citizen Spirit (1865)

- Flugschriften op. 300 Pamphlets (1865)

- Wiener Bonbons op. 307 Viennese Sweets (1866)

- Feenmärchen op. 312 Fairytales (1866)

- An der schönen blauen Donau op. 314 On the Beautiful Blue Danube (1867)

- Künstlerleben op. 316 Artists' Life (1867)

- Telegramme op. 318 Telegrams (1867)

- Die Publicisten op. 321 The Publicists (1868)

- G'schichten aus dem Wienerwald Tales from the Vienna Woods op. 325 (1868),

- Illustrationen op. 331 Illustrations (1869)

- Wein, Weib und Gesang op. 333 Wine, Women and Song (1869)

- Freuet Euch des Lebens op. 340 Enjoy Life (1870)

- Neu Wien op. 342 New Vienna (1870)

- Tausend und eine Nacht op. 346 Thousand and One Nights (1871)

- Wiener Blut (waltz) op. 354 Viennese Blood (1873)

- Carnevalsbilder op. 357 Carnival Pictures (1873)

- Bei uns Z'haus op. 361 At Home (1873)

- Wo die Zitronen blühen op. 364 Where the Lemons Blossom (1874)

- Du und du from Die Fledermaus op. 367 You and you (1874)

- Cagliostro-Walzer op. 370 (1875)

- O schöner Mai! op. 375 Oh Lovely May! (1877)

- Rosen aus dem Süden op. 388 Roses from the South (1880)

- Nordseebilder op. 390 North Sea Pictures (1880)

- Kuss-Walzer op. 400 Kiss Waltz (1881)

- Frühlingsstimmen op. 410 Voices of Spring (1883)

- Lagunen-Walzer op. 411 Lagoon Waltz (1883)

- Schatz-Walzer op. 418 Treasure Waltz (1885)

- Wiener Frauen op. 423 Viennese Ladies (1886)

- Donauweibchen op. 427 Danube Maiden (1887)

- Kaiser-Jubiläum-Jubelwalzer op. 434 Emperor Jubilation (1888)

- Kaiser-Walzer op. 437 Emperor Waltz (1888)

- Rathausball-Tänze op. 438 City Hall Ball (1890)

- Gross-Wien op. 440 Great Vienna (1891)

- Seid umschlungen, Millionen! op. 443 Be Embraced, You Millions! (1892)

- Klug Gretelein op. 462 Clever Gretel (1895)

- Trau, Schau, Wem! op. 463 Take Care in Whom You Trust! (1895)

- Farewell to America o. op.

Polka

- Herzenslust op. 3 Heart's Content

- Explosions-Polka op. 43

- Harmonie Polka op. 106

- Annen op. 117 (1852) Anna

- Veilchen op. 132 Violets

- Aurora op. 165

- Champagne-Polka op. 211

- Tritsch-Tratsch-Polka op. 214 (1858) Chit-chat

- Maskenzug op. 240 Masked Ball

- Perpetuum Mobile op. 257

- Demolirer Polka-française op. 269 Demolition Men (1862)

- Vergnügungszug op. 281 Journey Train (1864)

- S gibt nur a Kaiserstadt,'s gibt nur a Wien! op. 291 Only one Imperial City, one Vienna

- Kreuzfidel op. 301 Cross-Fiddling

- Lob der Frauen Polka-mazurka op. 315 Praise of Women

- Postillon D'Amour Polka-française op. 317 (1867)

- Leichtes Blut Galop op. 319 Light Blood (1867)

- Figaro-Polka op. 320

- Stadt und Land Polka-mazurka op. 322 Town and Country

- Ein Herz, ein Sinn! Polka-mazurka op. 323 One Heart, One Mind!

- Unter Donner und Blitz op. 324 Thunder & Lightning (1868)

- Freikugeln op. 326 Free-shooter (1868)

- Fata Morgana Polka-mazurka op. 330

- Éljen a Magyar! polka schnell op. 332 Long live the Magyar!

- Im Krapfenwald'l Polka-française op. 336 In Krapfen's Woods

- Im Sturmschritt op. 348 At the Double!

- Die Bajadere op. 351 The Bayadere

- Vom Donaustrande op. 358 By the Danube's Shores

- Bitte schön! Polka-française op. 372 If You Please! (1875)

- Auf der Jagd! op.373 On the Hunt! (1875)

- Banditen-Galopp op. 378 Bandits' Galop (1877)

- Waldine op. 385 (1879)

- Neue Pizzicato Polka op. 449 New Pizzicato Polka

- Klipp-Klapp Galopp op. 466

March

- Patrioten op. 8 (1845)

- Austria op.20 (1846)

- Fest op. 49 (1847)

- Revolutions-Marsch op. 54 (1848)

- Studenten-Marsch Students' March op. 56 (1848)

- Brünner Nationalgarde, op. 58 Brno National Guard (1848)

- Kaiser Franz Josef op. 67 Emperor Francis Joseph (1849)

- Triumph op. 69 (1850)

- Wiener Garnison op. 77 Viennese Garrison (1850)

- Ottinger Reiter op. 83 (1850)

- Kaiser-Jäger op. 93 (1851)

- Viribus unitis op. 96 “With United Strength” (1851)

- Grossfürsten op. 107 (1852)

- Sachsen-Kürassier op. 113 Saxon-Cuirassiers (1852)

- Wiener Jubel-Gruss op. 115 Viennese Joyful Greetings (1852)

- Kaiser-Franz-Josef-Rettungs-Jubel Op.126 Joy at Deliverance of Emperor Franz Josef (1853)

- Caroussel op.133 Carousel (1853)

- Kron op.139 (1853)

- Erzherzog Wilhelm Genesungs op.149 (1854)

- Napoleon op.156 (1854)

- Alliance (musical work) op. 158 (1854)

- Krönungs op.183 Coronation (1856)

- Fürst Bariatinsky op.212 (1858)

- Deutscher Kriegermarsch op.284 (1864)

- Verbrüderungs op.287 Fraternization (1864)

- Persischer Marsch op.289 Persian March (1864)

- Ägyptischer op.335 Egyptian March (1869)

- Indigo-Marsch op.339 (from Indigo und die vierzig Rauber)

- Hoch Osterreich! op.371 Hail Austria (from Cagliostro in Wien)

- Jubelfest op.396 Jubilee Festival (1881)

- Der Lustige Krieg op.397 (1882)

- Matador op.406 (on Themes from Das Spitzentuch der Königin) (1883)

- Habsburg Hoch! op. 408 Hail Habsburg (1882)

- Russischer Marsch op.426 Russian March (1886)

- Reiter op.428 (from Simplicius) (1888)

- Spanischer Marsch op.433 Spanish March (1888)

- Fest op.452 Festival (1893)

- Živio! op.456 Your Health (1894)

- Es war so wunderschön op.467 It Was So Wonderful (from Waldmeister) (1896)

- Deutschmeister Jubiläums op.470 (1896)

- Auf's Korn! op.478 Take Aim! (1898)

Quadrille

- Debut-Quadrille op. 2 (1844)

- Le beau Monde op. 199 Fashionable Society (1857)

- Indigo-Quadrille op. 344 (1871)

- Cagliostro-Quadrille op. 369 (1875)

Film adaptations

An Academy Award-winning 1953 Tom and Jerry cartoon, Johann Mouse, was made in honour of Johann Strauss II, and features the Kaiser-Walzer op.437.

After a trip to Vienna, Walt Disney was inspired to create four feature films. One of those was "The Waltz King", a loosely adapted biopic of Johann Strauss, which aired as part of the Wonderful World of Disney in the U.S. in 1963 while it gained theatrical distribution abroad.

The lives of the Strauss dynasty members and their world-renowned craft of composing Viennese waltzes are also briefly documented in several television adaptations, such as The Strauss Dynasty (1991)[12] and Strauss, the King of 3/4 Time (1995).[13]

Many other films used his works and melodies, and several films have been based upon the life of the musician, one of which is called The Great Waltz.

Alfred Hitchcock made a low-budget biopic of Strauss in 1933 called Waltzes from Vienna.

Media

See also

- List of Austrians in music

- List of Austrians

References

- Ganzl, Kurt. The Encyclopedia of Musical Theatre (3 Volumes). New York: Schirmer Books, 2001.

- Traubner, Richard. Operetta: A Theatrical History. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, 1983

- Jacob, H. E. Johann Strauss, Father and Son: A Century of Light Music. The Greystone Press, 1940.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 "Johann Strauss II". Grove Music Online. Retrieved on 2008-09-28.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Johann Strauss — End of an Era. Pennsylvania State University Press. pp. pg. 126.

- ↑ Johann Strauss, Father and Son: A Century of Light Music. The Greystone Press. pp. 127.

- ↑ The Waltz Kings. William Morrow & Company, Inc.. 1972. pp. pg. 96.

- ↑ Johann Strauss — End of an Era. Pennsylvania State University Press. pp. pg. 246.

- ↑ "Strauss: Johann Strauss II". Grove Music Online. Retrieved on 2008-09-28.

- ↑ Jewish roots of composer Johann Strauss emerging

- ↑ "Vienna Tickets >> Johann Strauss". Retrieved on 2008-10-03.

- ↑ Johann Strauss, Father and Son: A Century of Light Music. The Greystone Press. 1940. pp. pg. 227.

- ↑ Johann Strauss, Father and Son: A Century of Light Music. The Greystone Press. 1940. pp. pg. 341.

- ↑ Johann Strauss, Father and Son: A Century of Light Music. The Greystone Press. 1940. pp. pg. 363.

- ↑ The Strauss Dynasty (1991) at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Strauss, the King of 3/4 Time (1995) at the Internet Movie Database

External links

- A complete list of Strauss' compositions

- Johann Strauss Gallery

- List of Strauss's stage works with date, theatre information and links

- Free scores by Johann Strauss II in the International Music Score Library Project

- www.kreusch-sheet-music.net Free Scores by Strauss

- Johann Strauss in Vienna A funny video about Strauss and Vienna