Balfour Declaration of 1917

The Balfour Declaration of 1917 (dated November 2 1917) was a classified formal statement of policy by the British government stating that the British government "view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people" with the understanding that "nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country."

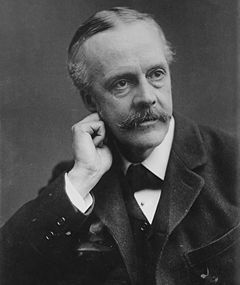

The declaration was made in a letter from Foreign Secretary Arthur James Balfour to Lord Rothschild (Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild), a leader of the British Jewish community, for transmission to the Zionist Federation, a private Zionist organization. The letter reflected the position of the British Cabinet, as agreed upon in a meeting on October 31 1917. It further stated that the declaration is a sign of "sympathy with Jewish Zionist aspirations."

The statement was issued through the efforts of Chaim Weizmann and Nahum Sokolow, the principal Zionist leaders based in London but, as they had asked for the reconstitution of Palestine as “the” Jewish national home, the Declaration fell short of Zionist expectations.[1]

The "Balfour Declaration" was later incorporated into the Sèvres peace treaty with Turkey and the Mandate for Palestine. The original document is kept at the British Library.

Contents |

Text of the declaration

The declaration, a typed letter signed in ink by Balfour, reads as follows:

Foreign Office,

November 2nd, 1917.

Dear Lord Rothschild,

I have much pleasure in conveying to you, on behalf of His Majesty's Government, the following declaration of sympathy with Jewish Zionist aspirations which has been submitted to, and approved by, the Cabinet:

"His Majesty's Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country".

I should be grateful if you would bring this declaration to the knowledge of the Zionist Federation.

Yours sincerely

Arthur James Balfour

Text development and differing views

The record of discussions that led up to the final text of the Balfour Declaration clarifies some details of its wording. The phrase "national home" was intentionally used instead of "state", and the British devoted some effort over the following decades, including Winston Churchill's 1922 White Paper, to denying that a state was the intention. However, in private, many British officials agreed with the interpretation of the Zionists that a state would be the eventual outcome.[2]

The initial draft of the declaration, contained in a letter sent by Rothschild to Balfour, referred to the principle "that Palestine should be reconstituted as the National Home of the Jewish people."[3] In the final text, the word that was replaced with in to avoid committing the entirety of Palestine to this purpose. Similarly, an early draft did not include the commitment that nothing should be done which might prejudice the rights of the non-Jewish communities. These changes came about partly as the result of the urgings of Edwin Samuel Montagu, an influential anti-Zionist Jew and Secretary of State for India, who, among others, was concerned that the declaration without those changes could result in increased anti-Semitic persecution. The draft was circulated and during October the government received replies from various representatives of the Jewish community. Lord Rothschild took exception to the new proviso on the basis that it presupposed the possibility of a danger to non-Zionists, which he denied.[4]

At that time the British were busy making promises. At a war Cabinet meeting, held on 31 October 1917, Balfour suggested that a declaration favorable to Zionist aspirations would allow Great Britain "to carry on extremely useful propaganda both in Russia and America"[5] The British also dropped Balfour Declaration leaflets written in Yiddish over Germany.[6]

Henry McMahon had exchanged letters with Hussein bin Ali, Sherif of Mecca, in 1915, in which he had promised Hussein control of Arab lands with the exception of 'portions of Syria' lying to the west of 'the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo'. Palestine lies to the south and wasn't explicitly mentioned. That modern-day Lebanese region of the Mediterranean coast was set aside as part of a future French Mandate. After the war, the extent of the coastal exclusion was hotly disputed. Hussein had protested that the Arabs of Beirut would greatly oppose isolation from the Arab state or states, but did not bring up the matter of the Jerusalem or Palestine. Dr. Chaim Weizmann in his autobiography Trial and Error that Palestine had been excluded from the areas that should have been Arab and independent. This interpretation was supported explicitly by the British government in the 1922 White Paper.

Lord Grey had been the Foreign Secretary during the McMahon-Hussein negotiations. Speaking in the House of Lords on the 27th March, 1923, he made it clear that, for his part, that he entertained serious doubts as to the validity of the British Government's interpretation of the pledges which he, as Foreign Secretary, had caused to be given to the Sharif Hussein in 1915. He called for all of the secret engagements regarding Palestine to be made public.[7] Many of the relevant documents in the National Archives were later declassified and published. Among them were the minutes of a Cabinet Eastern Committee meeting, chaired by Lord Curzon,which was held on 5 December 1918. Balfour was in attendance. The minutes revealed that in laying out the government's position Curzon had explained that: "Palestine was included in the areas as to which Great Britain pledged itself that they should be Arab and independent in the future".[8]

Milner as the chief author

In his posthumously published 1982 book The Anglo-American Establishment, Georgetown University history professor Carroll Quigley explained that the Balfour Declaration was actually drafted by Lord Alfred Milner. Quigley wrote:

"This declaration, which is always known as the Balfour Declaration, should rather be called 'the Milner Declaration,' since Milner was the actual draftsman and was apparently, its chief supporter in the War Cabinet. This fact was not made public until 21 July 1936. At that time Ormsby-Gore, speaking for the government in Commons, said, 'The draft as originally put up by Lord Balfour was not the final draft approved by the War Cabinet. The particular draft assented to by the War Cabinet and afterwards by the Allied Governments and by the United States. . .and finally embodied in the Mandate, happens to have been drafted by Lord Milner. The actual final draft had to be issued in the name of the Foreign Secretary, but the actual draftsman was Lord Milner."[9]

Negotiation

One of the main proponents of a Jewish homeland in Palestine was Dr. Chaim Weizmann, the leading spokesman for organized Zionism in Britain. Weizmann was a chemist who had developed a process to synthesize acetone via fermentation. Acetone is required for the production of cordite, a powerful propellant explosive needed to fire ammunition without generating tell-tale smoke. Germany had cornered supplies of calcium acetate, a major source of acetone. Other pre-war processes in Britain were inadequate to meet the increased demand in World War I, and a shortage of cordite would have severely hampered Britain's war effort. Lloyd-George, then Minister for Munitions, was grateful to Weizmann and so supported his Zionist aspirations. In his War Memoirs, Lloyd George wrote of meeting Weizmann in 1916 that Weizmann

- ... explained his aspirations as to the repatriation of the Jews to the sacred land they had made famous. That was the fount and origin of the famous declaration about the National Home for the Jews in Palestine .... As soon as I became Prime Minister I talked the whole matter over with Mr Balfour, who was then Foreign Secretary.

However, this version of the story of the declaration's origins has been described as "fanciful", a fair assessment considering that discussions between Weizmann and Balfour had begun at least a decade earlier. In late 1905 Balfour had requested of his Jewish constituency representative, Charles Dreyfus, that he arrange a meeting with Weizman, during which Weizman asked for official British support for Zionism, and they were to meet again on this issue in 1914.[10]

During the first meeting between Weizmann and Balfour in 1906, Balfour asked what Weizmann's objections were to the idea of a Jewish homeland in Uganda rather than in Palestine. According to Weizmann's memoir, the conversation went as follows:

- "Mr. Balfour, supposing I was to offer you Paris instead of London, would you take it?" He sat up, looked at me, and answered: "But Dr. Weizmann, we have London." "That is true," I said, "but we had Jerusalem when London was a marsh." He ... said two things which I remember vividly. The first was: "Are there many Jews who think like you?" I answered: "I believe I speak the mind of millions of Jews whom you will never see and who cannot speak for themselves." ... To this he said: "If that is so you will one day be a force."[11]

Conflicts and Broken Treaty Commitments

The Anglo-French Declaration of November 1918 pledged that Great Britain and France would "assist in the establishment of indigenous Governments and administrations in Syria and Mesopotamia by "setting up of national governments and administrations deriving their authority from the free exercise of the initiative and choice of the indigenous populations".

Balfour resigned as Foreign Secretary following the Versailles Conference in 1919, but continued in the Cabinet as Lord President of the Council. In a memorandum addressed to the new Foreign Secretary, Lord Curzon, he stated that the Balfour Declaration contradicted the letters of the covenant (referring to the League Covenant) the Anglo-French Declaration, and the instructions of the King-Crane Commission. All of the other engagements contained pledges that the Arab populations could establish national governments of their own choosing according to the principle of self-determination.

Balfour explained:

"The contradiction between the letters of the Covenant [of the League of Nations] and the policy of the Allies is even more flagrant in the case of the ‘independent nation’ of Palestine than in that of the ‘independent nation‘ of Syria. For in Palestine we do not propose to even go through the form of consulting the wishes of the present inhabitants of the country though the American Commission is going through the form of asking what they are.

The Four Great Powers [Britain, France, Italy and the United States] are committed to Zionism. And Zionism, be it right or wrong, good or bad, is rooted in age-long traditions, in present needs, and future hopes, of far profounder import than the desires and prejudices of the 700,000 Arabs who now inhabit that ancient land. In my opinion that is right.

What I have never been able to understand is how it can be harmonized with the [Anglo-French] declaration, the Covenant, or the instruction to the [King-Crane] Commission of Enquiry.

I do not think that Zionism will hurt the Arabs, but they will never say they want it. Whatever be the future of Palestine it is not now an ‘independent nation’, nor is it yet on the way to become one. Whatever deference should be paid to the views of those living there, the Powers in their selection of a mandatory do not propose, as I understand the matter, to consult them. In short, so far as Palestine is concerned, the Powers have made no statement of fact which is not admittedly wrong, and no declaration of policy which, at least in the letter, they have not always intended to violate.

If Zionism is to influence the Jewish problem throughout the world Palestine must be made available for the largest number of Jewish immigrants. It is therefore eminently desirable that it should obtain the command of the water-power which naturally belongs to it whether by extending its borders to the north, or by treaty with the mandatory of Syria, to whom the southward flowing waters of Hamon could not in any event be of much value.

For the same reason Palestine should be extended into the lands lying east of the Jordan. It should not, however, be allowed to include the Hedjaz Railway, which is too distinctly bound up with exclusively Arab Interests..." [12]

Controversy behind Declaration

British public and government opinion became increasingly less favorable to the commitment that had been made to Zionist policy. In Feb 1922 Winston Churchill, a fervent Zionist himself, telegraphed Herbert Samuel asking for cuts in expenditure and noting:

In both Houses of Parliament there is growing movement of hostility, against Zionist policy in Palestine, which will be stimulated by recent Northcliffe articles. I do not attach undue importance to this movement, but it is increasingly difficult to meet the argument that it is unfair to ask the British taxpayer, already overwhelmed with taxation, to bear the cost of imposing on Palestine an unpopular policy.[13]

Sir John Evelyn Shuckburgh of the new Middle East department of the Foreign Office discovered that the correspondence prior to the declaration was not available in the Colonial Office, 'although Foreign Office papers were understood to have been lengthy and to have covered a considerable period'." The 'most comprehensive explanation' of the origin of the Balfour Declaration the Foreign Office was able to provide was contained in a small 'unofficial' note of Jan 1923 affirming that:

little is known of how the policy represented by the Declaration was first given form. Four, or perhaps five men were chiefly concerned in the labour-the Earl of Balfour, the late Sir Mark Sykes, and Messrs. Weizmann and Sokolow, with perhaps Lord Rothschild as a figure in the background. Negotiations seem to have been mainly oral and by means of private notes and memoranda of which only the scantiest records are available, even if more exists.[14]

Arab opposition

The Arabs sensed danger in November 1918 at the parade marking the first anniversary of the Balfour Declaration. The Muslim-Christian Association protested the carrying of new 'white and blue banners with two inverted triangles in the middle'. They drew the attention of the authorities to the serious consequences of any political implications in raising the banners.[15]

Later that month, on the first anniversary of the occupation of Jaffa by the British, the Muslim-Christian Association sent a lengthy memorandum and petition to the military governor protesting once more the Zionist intrusion.[16]

References

- ↑ Balfour Declaration. (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved August 12, 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ↑ Mansfield, Peter (1992). The Arabs. London: Penguin Books. pp. 176–77.

- ↑ Stein, Leonard (1961). The Balfour Declaration. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 470.

- ↑ Palestine Papers 1917-1922, Doreen Ingrams, page 13

- ↑ Palestine Papers 1917-1922, Doreen Ingrams, page 16

- ↑ 90th Anniversary Of Balfour Declaration

- ↑ Report of a Committee Set Up To Consider Certain Correspondence Between Sir Henry McMahon and The Sharif of Mecca

- ↑ cited in Palestine Papers, 1917-1922, Doreen Ingrams, page 48 from the UK Archive files PRO CAB 27/24.

- ↑ Quigley, Carroll (1981). The Anglo-American Establishment. New York: Books in Focus. pp. 169. ISBN 0945001010. http://www.alexanderhamiltoninstitute.org/lp/Hancock/CD-ROMS/GlobalFederation%5CWorld%20Trade%20Federation%20-%20136%20-%20The%20Anglo-American%20Establishment.html.

- ↑ Harry Defries, Conservative Party Attitudes to Jews 1900-1950, Routledge, 2001, ISBN 0714652210. pp.50-51.

- ↑ Weizmann, Trial and Error, p.111, as quoted in W. Lacquer, The History of Zionism", 2003, ISBN 1860649327. p.188

- ↑ Edward Said (1992). 'Question of Palestine'. Vintage Books Edition. p. 16. ISBN 0679739882., Doreen Ingrams (1973). 'Palestine Papers 1917-1922'. George Braziller Edition. p. 73. ISBN 0807606480. Documents on British Foreign Policy 1919-1931, First series Vol 4. page 345 memorandum from Lord Balfour to Lord Curzon, August 11, 1919, and quoted by The Origin of the Palestine-Israeli Conflict 2nd Edition, 2002, Jews for Justice. Verified 24 Oct 2007.

- ↑ CO 733/18, Churchill to Samuel, Telegram, Private and Personal, 25 February 1922. Cited Huneidi, Sahar "A Broken Trust, Herbert Samuel, Zionism and the Palestinians" 2001, ISBN 1-86064-172-5, p.57.

- ↑ Full text of note included CO 733/58, Secret Cabinet Paper CP 60 (23), 'Palestine and the Balfour Declaration, January 1923. FO unofficial note added 'little referring to the Balfour Declaration among such papers as have been preserved'. Shuckburgh's memo asserts that 'as the official records are silent, it can only be assumed that such discussions as had taken place were of an informal and private character'.[1]

- ↑ Zu'aytir, Akram, Watha'iq al-haraka a-wataniyya al-filastiniyya (1918-1939), ed. Bayan Nuwayhid al-Hut. Beirut 1948. Papers, p. 5. Cited by Huneidi, Sahar "A Broken Trust, Herbert Samuel, Zionism and the Palestinians". ISBN 1-86064-172-5 p.32.

- ↑ 'Petition from the Moslem-Christian Association in Jaffa, to the Military Governor, on the occasion of the First Anniversary of British Entry into Jaffa', 16 November 1918, Zu'aytir papers pp. 7-8. Cited by Huneidi p.32.

See also

- Napoleon and a Jewish state in Palestine

- Faisal-Weizmann Agreement

- British Mandate of Palestine

- 1947 UN Partition Plan

- Declaration of Independence (Israel), May 14 1948

- Madagascar Plan

- British Uganda Program

- Benjamin Freedman

External links

- Balfour Declaration lexicon entry Knesset website (English)

- Happy Birthday Balfour Declaration- 91 Years Later- Jerusalem Post

- Text of the 1922 White Paper from the Avalon Project

- Donald Macintyre, The Independent, 26 May 2005, "The birth of modern Israel: A scrap of paper that changed history"

- Avi Shlaim. "The Balfour Declaration and Its Consequences". Retrieved on 2007-06-21.

- Balfour: 117 words that changed the face of the Middle East

- From the Balfour Declaration to Partition … to Two States?

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||