Jane Eyre

| Jane Eyre | |

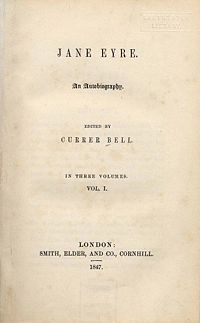

Title page of the first edition of Jane Eyre |

|

| Author | Charlotte Brontë |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Novel |

| Publisher | Smith Elder and Co., Cornhill |

| Publication date | 16 October 1847 |

| Media type | |

Jane Eyre (IPA: /dʒeɪn ɛər/) is a famous and influential novel by English writer Charlotte Brontë. It was published in London, England in 1847 by Smith, Elder & Co. (Harper & Brothers of New York came out with the American edition in 1848.)

Contents |

Plot introduction

Jane Eyre is a first-person narrative of the title character, a small, plain-faced, intelligent and honest English orphan. The novel goes through five distinct stages: Jane's childhood at Gateshead, where she is abused by her aunt and cousins; her education at Lowood School, where she acquires friends and role models but also suffers privations; her time as the governess of Thornfield Manor, where she falls in love with her Byronic employer, Edward Rochester; her time with the Rivers family at Marsh's End (or Moor House) and Morton, where her cold clergyman-cousin St John Rivers proposes to her; and her reunion with and marriage to her beloved Rochester at his house of Ferndean. Partly autobiographical, the novel abounds with social criticism and sinister gothic elements.

Jane Eyre is divided into 38 chapters; most editions are at least 400 pages long (although the preface and introduction on certain copies are liable to take up another 100). The original was published in three volumes, comprising chapters one to 15, 16 to 26, and 27 to 38.

Plot summary

There was no possibility of taking a walk that day. We had been wandering, indeed, in the leafless shrubbery an hour in the morning; but since dinner (Mrs. Reed, when there was no company, dined early) the cold winter wind had brought with it clouds so sombre, and a rain so penetrating, that further out-door exercise was now out of the question.

– Excerpt from Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre, beginning of chapter 1

The novel begins in Gateshead Hall, where a ten-year-old orphan named Jane Eyre is living with her mother's brother's family. The brother, surnamed Reed, dies shortly after adopting Jane. His wife, Mrs. Sarah Reed, and their three children (John, Eliza and Georgiana) neglect and abuse Jane, for they resent Mr. Reed's preference for the little orphan in their midst. In addition, they dislike Jane's plain looks and quiet yet passionate character. The novel begins with young John Reed bullying Jane, who retaliates with unwanted violence. Jane is blamed for the ensuing fight, and Mrs. Reed has two servants drag her off and lock her up in the "red-room", the unused chamber in which Mr. Reed died. Still locked in that night, Jane sees a light and panics, thinking that her uncle's ghost has come. Her scream rouses the house, but Mrs. Reed just locks her up for a longer period of time. Then Jane has a fit and passes out. A doctor, Mr. Lloyd, comes to Gateshead Hall and suggests that Jane go to school.

Mr. Brocklehurst is a cold, cruel, self-righteous, and highly hypocritical clergyman who runs a charity school called Lowood Institution. He accepts Jane as a pupil in his school, but she is infuriated when Mrs. Reed tells him, falsely, that she is a liar. After Brocklehurst departs, Jane bluntly tells Mrs. Reed how she hates the Reed family. Mrs. Reed, so shocked that she is scarcely capable of responding, leaves the drawing room in haste.

Jane finds life at Lowood grim. Miss Maria Temple, the youthful superintendent, is just and kind, but another teacher, Miss Scatcherd, is sour and abusive. Mr. Brocklehurst, visiting the school for an inspection, has Jane placed on a tall stool before the entire assemblage. He then tells them that "...this girl, this child, the native of a Christian land, worse than many a little heathen who says its prayers to Brahma and kneels before Juggernaut—this girl is—a liar!"

Later that day, Miss Temple allows Jane to speak in her own defense. After Jane does so, Miss Temple writes to Mr. Lloyd. His reply agrees with Jane's, and she is cleared of Mr. Brocklehurst's accusation.

Mr. Brocklehurst embezzles the school's funds to support his family's luxurious lifestyle while hypocritically preaching to others a doctrine of privation and poverty. As a result, Lowood's eighty pupils must make do with cold rooms, poor meals and thin garments whilst his family lives in comfort. The majority become sick from a typhus epidemic that strikes the school.

Jane is impressed with one pupil, Helen Burns, who accepts Miss Scatcherd's cruelty and the school's deficiencies with passive dignity, practicing the Christian teaching of turning the other cheek. Jane admires and loves the gentle Helen and they become best friends, but Jane cannot bring herself to emulate her friend's behaviour. While the typhus epidemic is raging, Helen dies of consumption (tuberculosis) in Jane's arms.

Many die in the typhus epidemic, and Mr. Brocklehurst's neglect and dishonesty are laid bare. Several rich and kindly people donate to put up a new school building in a more healthful location. New rules are made, and improvements in diet and clothing are introduced. Though Mr. Brocklehurst cannot be overlooked, due to his wealth and family connections, new people are brought in to share his duties of treasurer and inspector, and conditions improve dramatically at the school.

The narrative resumes eight years later. Jane has been a teacher at Lowood for two years, but she thirsts for a better and brighter future. She advertises as a governess and is hired by Mrs. Alice Fairfax, housekeeper of the Gothic manor, Thornfield, to teach a rather spoiled but amiable little French girl named Adèle Varens. A few months after her arrival at Thornfield, Jane goes for a walk and aids a horseman who has taken a fall. He is rude to her and calls her a witch, but she helps him back on the horse nonetheless. On her return to Thornfield, Jane discovers that the horseman is her employer, Mr. Edward Rochester, an ugly, moody yet wonderful, passionate, Byronic, and charismatic gentleman nearly twenty years older than she. Adèle is his ward.

Rochester seems quite taken with Jane. He repeatedly summons her to his presence and talks with her. Jane is happy at Thornfield, but there are soon events to tarnish her new happiness: a strange laugh in the halls, a near fatal fire from which she has to save the master of the house, an attack upon a houseguest and a romantic rival: Miss Blanche Ingram.

Jane receives word that Mrs. Reed, upon hearing of her son John's apparent suicide after leading a life of dissipation and debt, has suffered a near-fatal stroke and is asking for her. Jane returns to Gateshead.

Although she rejects Jane's efforts at reconciliation, Mrs. Reed gives Jane a letter that she had previously withheld out of spite. The letter is from Jane's father's brother, John Eyre, notifying her of his intent to leave her his fortune upon his death.

About a fortnight after Jane's return to Thornfield, Jane, after months of concealing her emotions, vehemently proclaims her love for Edward, who in turn passionately proposes to her. Following a month of courtship, Jane's forebodings arise when a strange, savage-looking woman sneaks into her room one night and rips her wedding veil in two. Yet again, Rochester attributes the incident to Grace Poole.

The wedding goes ahead nevertheless. But during the ceremony in the church, the mysterious Mr. Mason and a lawyer step forth and declare that Rochester cannot marry Jane because his own wife is still alive. Rochester bitterly and sarcastically admits this fact, explaining that his wife is a violent madwoman whom he keeps imprisoned in the attic, where Grace Poole looks after her. But Grace Poole imbibes gin immoderately, occasionally giving the madwoman an opportunity to escape. It is Rochester's mad wife who is responsible for the strange events at Thornfield. Rochester nearly committed bigamy, and kept this fact from Jane. The wedding is cancelled, and Jane is heartbroken.

Rochester then asks Jane to accompany him to the south of France, where they will live as husband and wife, even though they cannot be married. But though she still loves him, Jane refuses to betray the God-given morals and principles she has always believed in.

In the dead of night, she slips out of Thornfield and takes a coach far away to the north of England. When her money gives out, she sleeps outdoors on the moor and reluctantly begs for food. One night, freezing and starving, she comes to Moor House (or Marsh End) and begs for help. St. John Rivers, the young clergyman who lives in the house, admits her.

Jane, who gives the false surname of Elliott, quickly recovers under the care of St. John and his two kind sisters, Diana and Mary. St. John arranges for Jane to teach a charity school for girls in the village of Morton.

Suspecting Jane's true identity, St. John Rivers relates Jane's experiences at Thornfield and says that her uncle, John Eyre, has died and left Jane his fortune of 20,000 pounds. After confessing her true identity, Jane arranges to share her inheritance with the Riverses, who turn out to be her cousins.

St. John intends to travel to India and devote his life to missionary work. He asks Jane to accompany him as his wife. Jane consents to go to India but adamantly refuses to marry him because they are not in love. St. John continues to pressure Jane to marry him, and his forceful personality almost causes her to capitulate. But at that moment she hears what she thinks is Rochester's voice calling her name, and this gives her the strength to reject St. John completely.

The next day, Jane takes a coach to Thornfield. But only blackened ruins lie where the manorhouse once stood. An innkeeper tells Jane that Rochester's mad wife set the fire and then committed suicide by jumping from the roof. Rochester rescued the servants from the burning mansion but lost a hand and his eyesight in the process. He now lives in an isolated manor house called Ferndean. Going to Ferndean, Jane reunites with Rochester. At first, he fears that she will refuse to marry a blind cripple, but Jane accepts him without hesitation. Rochester eventually recovers sight in one eye, and can see their first-born son when the baby is born.

Characters

- Jane Eyre: The protagonist and title character, orphaned as a baby. She is a plain-featured, small and reserved but talented, empathetic, hard-working, honest (not to say blunt), and passionate girl. Skilled at studying, drawing, and teaching, she works as a governess at Thornfield Manor and falls in love with her wealthy employer, Edward Rochester. But her strong sense of conscience does not permit her to become his mistress, and she does not return to him until his insane wife is dead and she herself has come into an inheritance.

- Mr. Reed: Jane's maternal uncle. He adopts Jane when her parents die. Before his own death, he makes his wife promise to care for Jane.

- Mrs. Sarah Reed: Jane's aunt by marriage, who resides at Gateshead. Because her husband insists, Mrs. Reed adopts Jane. Jane, however, receives nothing but neglect and abuse at her hands. At the age of ten, Jane is sent away to a charity school. Years later, Jane attempts to reconcile with her aunt, but Mrs. Reed spurns her, still resenting that her husband loved Jane more than his own children and that Jane had stood up to her and called her heartless shortly before being sent away to school. Shortly afterward, Mrs. Reed dies of a stroke.

- John Reed: Mrs. Reed's son, and Jane's cousin. He is Mrs. Reed's "own darling," though he bullies Jane constantly, sometimes in his mother's presence. His mother dotes on him, but he treats her condescendingly. He goes to college, ruining himself and Gateshead through gambling. Word comes of his death by suicide.

- Eliza Reed: Mrs. Reed's elder daughter, and Jane's cousin. Bitter because she is not as attractive as her sister, Georgiana Reed, she devotes herself self-righteously to Catholicism. After her mother's death, she enters a French convent, where she eventually becomes the Mother Superior.

- Georgiana Reed: Mrs. Reed's younger daughter, and Jane's cousin. Though spiteful and insolent, she is indulged by everyone at Gateshead because of her beauty. In London, Lord Edwin Vere falls in love with her, but his relations are against their marriage. Lord Vere and Georgiana decide to elope, but Eliza finds them out. Georgiana returns to Gateshead, where she grows plump and vapid, spending most of her time talking of her love affair. After Mrs. Reed's death, she marries a wealthy but worn-out society man.

- Bessie Lee: The plain-spoken nursemaid at Gateshead. She sometimes treats Jane kindly, telling her stories and singing her songs. Later she marries Robert Leaven.

- Robert Leaven: The coachman at Gateshead, who sometimes gives Jane a ride on Georgiana's bay pony. He brings Jane to Lowood Institution. Months after she goes to Thornfield Hall, he brings her the news of John Reed's death, which had brought on Mrs. Reed's stroke.

- Mr. Lloyd: A compassionate apothecary who recommends that Jane be sent to school. Later, he writes a letter to Miss Temple confirming Jane's account of her childhood and thereby clearing Jane of Mrs. Reed's charge of lying.

- Mr. Brocklehurst: The arrogant, hypocritical clergyman who serves as headmaster and treasurer of Lowood School. He embezzles the school's funds in order to pay for his family's opulent lifestyle. At the same time, he preaches a doctrine of Christian austerity and self-sacrifice to everyone in hearing. When his dishonesty is brought to light, he is made to share his office of inspector and treasurer with more kindly people, who greatly improve the school.

- Miss Maria Temple: The kind, attractive young superintendent of Lowood School. She recognizes Mr. Brocklehurst for the cruel hypocrite he is, and treats Jane and Helen with respect and compassion. She helps clear Jane of Mrs. Reed's false accusation of deceit.

- Miss Scatcherd: A sour and vicious teacher at Lowood. She behaves with particular cruelty toward Helen, using her as a scapegoat for anything and everything.

- Helen Burns: An angelic fellow-student and best friend of Jane's at Lowood School. Several years older than the ten-year-old Jane, she stoically accepts all the cruelties of the teachers and the deficiencies of the school's room and board. She refuses to hate the tyrannical Mr. Brocklehurst or the vicious Miss Scatcherd, or to complain, believing in the New Testament teaching that one should love one's enemies and turn the other cheek. Jane reveres her for her profound Christianity, even though she herself believes that returning hate for hate is necessary to prevent evil from taking over. Helen, uncomplaining as ever, dies of consumption in Jane's arms. In the book it is noted that she was buried in an unmarked grave until some years later, when a marble gravestone with her name and the word 'Resurgam' inscribed on it appears. The possible inference is that this was provided by Jane.

- Edward Fairfax Rochester: The owner of Thornfield Manor, and Jane's lover and eventual husband. He possesses a strong physique and great wealth, but his face is very plain and his moods prone to frequent change. Impetuous and sensual, he falls madly in love with Jane because her simplicity, bluntness, intellectual capacity and plainness contrast so much with those of the shallow society women to whom he is accustomed. But his unfortunate marriage to the maniacal Bertha Mason postpones his union with Jane, and he loses a hand and his eyesight while trying to rescue his mad wife after she sets a fire that burns down Thornfield. He is a Byronic hero.

- Bertha Mason: The violently insane secret wife of Edward Rochester. From the West Indies and of Creole extraction, her family possesses a strong strain of madness, of which Rochester did not know until, lured by her wealth and beauty, he had married her. Her insanity manifests itself in a few years, and Rochester resorts to imprisoning her in the attic of Thornfield Manor. She escapes four times during the novel and wreaks havoc in the house, the fourth time actually burning it down and taking her own life in the process.

- Adèle Varens: A naive, vivacious and rather spoiled French child to whom Jane is governess at Thornfield. She is Rochester's ward because her mother, Celine Varens, an opportunistic French opera dancer and singer, was Rochester's mistress. Rochester does not believe himself to be Adèle's father. Although not particularly fond of her, he nonetheless extends the little girl the best of care. In time, she grows up to be a very pleasant and well-mannered young woman.

- Mrs. Alice Fairfax: An elderly widow and housekeeper of Thornfield Manor. She treats Jane kindly and respectfully, but disapproves of her engagement to Mr Rochester.

- Blanche Ingram: A beautiful but self-absorbed, cruel and shallow socialite whom Mr. Rochester appears to court in order to make Jane jealous. Blanche despises the rather dowdy protagonist because she is a governess. Later Jane discovers Blanche Ingram did not love Mr. Rochester but rather his fortune.

- Richard Mason: A strangely blank-eyed but handsome Englishman from the West Indies, he stops Jane and Rochester's wedding with the proclamation that Rochester is still married to Bertha Mason, his sister.

- St. John Eyre Rivers: A clergyman who is Jane Eyre's cousin on her father's side. He is a devout, almost fanatical Christian of Calvinistic leanings. He is charitable, honest, patient, forgiving, scrupulous, austere and deeply moral; with these qualities alone, he would have made a saint. But he is also proud, cold, exacting, controlling and unwilling to listen to dissenting opinions. He was in love with Rosamond Oliver, but did not propose to her because he felt that she would not make a "suitable" wife. Jane venerates him and likes him, regarding him as a brother, but she refuses to marry him because he doesn't love her and is incapable of real kindness.

- Diana and Mary Rivers: St. John's sisters and Jane's cousins, they are kind and intellectual young women who contrive to lead an independent life while retaining their intelligence, purity and sense of meaning in life. Diana warns Jane against marrying her icy brother.

- Grace Poole: Bertha Mason's keeper, a frumpish woman verging on middle age. She drinks gin immoderately, occasionally giving her maniacal charge a chance to escape. Rochester and Mrs. Fairfax attribute all of Bertha's misdeeds to her.

- Rosamond Oliver: The rather shallow and coquettish, but beautiful and good-natured daughter of Morton's richest man. She donates the funds to launch the village school because she is in love with St. John. However, as St.John refuses to let himself love her, she in time becomes engaged to the wealthy Mr. Granby.

- John Eyre: Jane's paternal uncle, who leaves her his vast fortune of 20,000 pounds. He never appears as a character. Has distant relations with St. John. Leaves him and his sisters 31 pounds and 10 shillings (i.e. 30 guineas) as a result. Jane divides her 20,000 pounds amongst the four of them (St. John, Mary, Diana and herself) leaving each with 5,000 pounds.

Themes

Morality

Jane refuses to become Rochester's paramour because of her "impassioned self-respect and moral conviction." She rejects St. John Rivers's puritanism as much as Rochester's libertinism. Instead, she works out a morality expressed in love, independence, and forgiveness.[1] Specifically, she forgives her cruel aunt and loves her husband, but never surrenders her independence to him, even after they are married. He is blind, and thus more dependent on her than she on him.

Religion

Throughout the novel, Jane endeavours to attain an equilibrium between moral duty and earthly happiness. She despises the hypocritical puritanism of Mr. Brocklehurst, and rejects St. John Rivers' cold devotion to his perceived Christian duty, but neither can she bring herself to emulate Helen Burns' turning the other cheek, although she admires Helen for it. Ultimately, she rejects these three extremes and finds a middle ground in which religion serves to curb her immoderate passions but does not repress her true self.

Social class

Jane's ambiguous social position—a penniless yet learned orphan from a good family—leads her to criticise discrimination based on class. Although she is educated, well-mannered, and relatively sophisticated, she is still a governess, a paid servant of low social standing, and therefore powerless. Nevertheless, Brontë possesses certain class prejudices herself, as is made clear when Jane has to remind herself that her unsophisticated village pupils at Morton "are of flesh and blood as good as the scions of gentlest genealogy."

Gender relations

A particularly important theme in the novel is patriarchalism and Jane's efforts to assert her own identity within male-dominated society. Three of the main male characters, Brocklehurst, Rochester and St. John, try to keep Jane in a subordinate position and prevent her from expressing her own thoughts and feelings. Jane escapes Brocklehurst and rejects St. John, and she only marries Rochester once she is sure that theirs is a marriage between equals. Through Jane, Brontë refutes Victorian stereotypes about women, articulating what was for her time a radical feminist philosophy:

Women are supposed to be very calm generally: but women feel just as men feel; they need exercise for their faculties, and a field for their efforts as much as their brothers do; they suffer from too rigid a restraint, too absolute a stagnation, precisely as men would suffer; and it is narrow-minded in their more privileged fellow-creatures to say that they ought to confine themselves to making puddings and knitting stockings, to playing on the piano and embroidering bags. It is thoughtless to condemn them, or laugh at them, if they seek to do more or learn more than custom has pronounced necessary for their sex. (Chapter XII)

Disability

Recent scholarship has also begun to explore themes in the novel relating to disability, looking at the madness of Bertha Mason Rochester, the blinding and maiming of Rochester,[2] and the unusual affect of the heroine, perhaps suggestive of autism or Asperger's Syndrome.[3]

Context

The early sequences, in which Jane is sent to Lowood, a harsh boarding school, are derived from the author's own experiences. Helen Burns's death from tuberculosis (referred to as consumption) recalls the deaths of Charlotte Brontë's sisters Elizabeth and Maria, who died of the disease in childhood as a result of the conditions at their school, the Clergy Daughters School at Cowan Bridge, near Tunstall, Lancashire. Mr. Brocklehurst is based on Rev. William Carus Wilson (1791–1859), the Evangelical minister who ran the school, and Helen Burns is likely modelled on Charlotte's sister Maria. Additionally, John Reed's decline into alcoholism and dissolution recalls the life of Charlotte's brother Branwell, who became an opium and alcohol addict in the years preceding his death. Finally, like Jane, Charlotte becomes a governess. These facts were revealed to the public in The Life of Charlotte Brontë (1857) by Charlotte's friend and fellow novelist Elizabeth Gaskell.[4]

The Gothic manor of Thornfield was probably inspired by North Lees Hall, near Hathersage in the Peak District. This was visited by Charlotte Brontë and her friend Ellen Nussey in the summer of 1845 and is described by the latter in a letter dated 22 July 1845. It was the residence of the Eyre family, and its first owner, Agnes Ashurst, was reputedly confined as a lunatic in a padded second floor room.[4]

Literary motifs and allusions

Jane Eyre uses many motifs from Gothic fiction, such as the Gothic manor (Thornfield), the Byronic hero (Rochester and Jane herself) and The Madwoman in the Attic (Bertha), whom Jane perceives as resembling "the foul German spectre—the vampire" (Chapter XXV) and who attacks her own brother in a distinctly vampiric way: "She sucked the blood: she said she'd drain my heart" (Chapter XX). Also, besides gothicism, Jane Eyre displays romanticism to create a unique Victorian novel.

Literary allusions from the Bible, fairy tales, The Pilgrim's Progress, Paradise Lost, and the novels and poetry of Sir Walter Scott are also much in evidence.[4] The novel deliberately avoids some conventions of Victorian fiction, not contriving a deathbed reconciliation between Aunt Reed and Jane Eyre and avoiding the portrayal of a "fallen woman".

Adaptations

Jane Eyre has engendered numerous adaptations and related works inspired by the novel:

Silent film versions

- Three adaptations entitled Jane Eyre were released; one in 1910, two in 1914.

- 1915: Jane Eyre starring Louise Vale.[2]

- 1915: A version was released called The Castle of Thornfield.

- 1918: A version was released called Woman and Wife.

- 1921: Jane Eyre starring Mabel Ballin.[3]

- 1926: A version was made in Germany called Orphan of Lowood.

Motion Picture versions

- 1934: Jane Eyre, starring Colin Clive and Virginia Bruce.[4]

- 1940: Rebecca, directed by Alfred Hitchcock and based upon the novel of the same name which was influenced by Jane Eyre.[5]Joan Fontaine, who starred in this film, would also be cast in the 1944 version of Jane Eyre to reinforce the connection.[6]

- 1943: I Walked with a Zombie is a horror movie loosely based upon Jane Eyre.

- 1944: Jane Eyre, with a screenplay by John Houseman and Aldous Huxley. It features Orson Welles as Rochester, Joan Fontaine as Jane, Margaret O'Brien as Adele and Elizabeth Taylor as Helen Burns.

- 1956: A version was made in Hong Kong called The Orphan Girl.

- 1963: A version was released in Mexico called El Secreto (English: "The Secret").

- 1970: Jane Eyre, starring George C. Scott as Rochester and Susannah York as Jane.

- 1972: An adaptation in Telugu, Shanti Nilayam, directed by C. Vaikuntarama Sastry, starring Anjali Devi.

- 1973: BBC miniseries starring Sorcha Cusack as Jane Eyre and Michael Jayston as Rochester

- 1978: A version was released in Mexico called Ardiente Secreto (English: "Ardent Secret").

- 1996: Jane Eyre, directed by Franco Zeffirelli and starring William Hurt as Rochester, Charlotte Gainsbourg as Jane, Elle Macpherson as Blanche Ingram, Anna Paquin as the young Jane, and Geraldine Chaplin as Miss Scatcherd.

- 1997: Directed by Robert Young, starring Ciaran Hinds as Rochester and Samantha Morton as Jane Eyre.

- 2008: A new film starring Ellen Page in the title role.(shown on the bbc)

Musical versions

- A two-act ballet of Jane Eyre was created for the first time by the London Children's Ballet in 1994, with an original score by composer Julia Gomelskaya and choreography by Polyanna Buckingham. The run was a sell-out success.

- A musical version with a book by John Caird and music and lyrics by Paul Gordon, with Marla Schaffel as Jane and James Stacy Barbour as Rochester, opened at the Brooks Atkinson Theatre on 10 December 2000. It closed on 10 June 2001.

- An opera version was written in 2000 by English composer Michael Berkeley, with a libretto by David Malouf. It was given its premiere by Music Theater Wales at the Cheltenham Festival.

- Jane Eyre was played for the first time in Europe in Beveren, Belgium. It was given its premiere at the cultural centred.

- The ballet "Jane," based on the book was created in 2007, a Bullard/Tye production with music by Max Reger. Its world premiere was scheduled at the Civic Auditorium, Kalamazoo, Michigan, June 29 and 30, performed by the Kalamazoo Ballet Company, Therese Bullard, Director.

- A musical production directed by Debby Race, book by Jana Smith and Wayne R. Scott, with a musical score by Jana Smith and Brad Roseborough, premiered in 2008 at the Lifehouse Theatre in Redlands, California[5]

Television versions

- 1952: This was a live television production presented by "Westinghouse Studio One (Summer Theatre)"[7]

- Adaptations appeared on British and American television in 1956 and 1961.

- 1963:Jane Eyre. It was produced by the BBC and starred Richard Leech as Rochester and Ann Bell as Jane. [8]

- 1973: Jane Eyre. It was produced by the BBC and starred Sorcha Cusack as Jane, Michael Jayston as Rochester, Juliet Waley as the child Jane, and Tina Heath as Helen Burns.

- 1983: Jane Eyre. It was produced by the BBC and starred Zelah Clarke as Jane, Timothy Dalton as Rochester, Sian Pattenden as the child Jane, and Colette Barker as Helen Burns.

- 1997: Jane Eyre. It was produced by the A&E Network and starred Ciaran Hinds as Rochester and Samantha Morton as Jane.

- 2006: Jane Eyre. It was produced by the BBC and starred Toby Stephens as Rochester, Ruth Wilson as Jane, and Georgie Henley as Young Jane.

Literature

- 1938: Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier was partially inspired by Jane Eyre.[9][10]

- 1961: The Ivy Tree by Mary Stewart adapts many of the motifs of Jane Eyre to 1950's northern England. The main character, Annabel, falls in love with her older neighbor who is married to a mentally ill woman. Like Jane, Annabel runs away to try to get over her love. The novel begins when she returns from her eight-year exile.

- 1966: Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys. The character, Bertha Mason, serves as the main protagonist for this novel which acts as a "prequel" to Jane Eyre. It describes the meeting and marriage of Antoinette (later renamed Bertha by Rochester) and Rochester. In its reshaping of events related to Jane Eyre, the novel suggests that Bertha's madness is the result of Rochester's rejection of her and her Creole heritage. It was also adapted into film twice.

- 1997: Mrs Rochester: A Sequel to Jane Eyre by Hilary Bailey

- 2000: Adele: Jane Eyre's Hidden Story by Emma Tennant

- 2000: Jane Rochester by Kimberly A. Bennett, content explores the first years of the Rochester's marriage with gothic and explicit content. A fan favorite.

- 2001 novel The Eyre Affair by Jasper Fforde revolves around the plot of Jane Eyre. It portrays the book as originally largely free of literary contrivance: Jane and Rochester's first meeting is a simple conversation without the dramatic horse accident, and Jane does not hear his voice calling for her and ends up starting a new life in India. The title heroine's efforts mostly accidentally change it to the real version.

- 2002: Jenna Starborn by Sharon Shinn, a science fiction novel based upon Jane Eyre

- 2006: The French Dancer's Bastard: The Story of Adele From Jane Eyre by Emma Tennant. This is a slightly modified version of Tennant's 2000 novel.

- 2007: Thornfield Hall: Jane Eyre's Hidden Story by Emma Tennant. This is another version of Jane Eyre.

- The novelist Angela Carter was working on a sequel to Jane Eyre at the time of her death in 1992. This was to have been the story of Jane's stepdaughter Adèle Varens and her mother Celine. Sadly, only a synopsis survives.[6]

References

- ↑ "Brontë, Charlotte." Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1987. p. 546.

- ↑ David Bolt, "The blindman in the classic: feminisms, ocularcentrism and Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre," Textual Practice 22.2 (June 2008): 269-89.

- ↑ Julia Miele Rodas, “'On the Spectrum': Rereading Contact and Affect in Jane Eyre," Nineteenth-Century Gender Studies 4.2 (Summer 2008): [1]

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Stevie Davies, Introduction and Notes to Jane Eyre. Penguin Classics ed., 2006.

- ↑ Lifehouse Theatre presents Jane Eyre - accessed May 10th, 2008

- ↑ http://www.guardian.co.uk/stage/2006/jan/29/theatre.angelacarter?gusrc=rss&feed=books

External links

- Read Jane Eyre in Tomeraider format for free.

- Jane Eyre at The Victorian Web

- Jane Eyre at the Brontë Parsonage Museum Website

- Jane Eyre Italian site

- The Bronte Society website

- Dutch website on the Brontës

The novel online

- A page by page reproduction of the Penguin Classics version of Jane Eyre

- A page by page reproduction of the Oxford World Classics version of Jane Eyre

- Full text of Jane Eyre at Project Gutenberg

- Jane Eyre, read book online, separated by page

- Complete Audiobook MP3 - Public Domain

- Jane Eyre free downloads in PDF, PDB and LIT formats

- Full text of Jane Eyre on Sparknotes

- "Jane Eyre" AudioText complete novel eText with Audio narration on the same page, plus clickable definitions for every word!

|

|||||||||||||||||