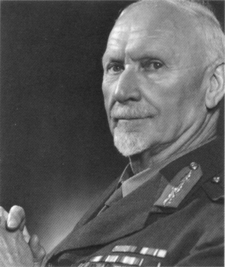

Jan Smuts

|

Jan Christiaan Smuts

|

|

|

|

|

Prime Minister of South Africa

|

|

|---|---|

| In office 5 September 1939 – 4 June 1948 |

|

| Preceded by | James Barry Munnik Hertzog |

| Succeeded by | Daniel François Malan |

| In office 3 September 1919 – 30 June 1924 |

|

| Preceded by | Louis Botha |

| Succeeded by | James Barry Munnik Hertzog |

|

|

|

| Born | 24 May 1870 Bovenplaats, near Malmesbury, Cape Colony (now South Africa) |

| Died | 11 September 1950 (aged 80) Doornkloof, Irene, near Pretoria, South Africa |

| Political party | South African Party United Party |

| Spouse | Isie Krige |

| Religion | Calvinist |

Field Marshal Jan Christiaan Smuts, OM, CH, PC, ED, KC, FRS (24 May 1870 – 11 September 1950) was a prominent South African and British Commonwealth statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various cabinet posts, he served as Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa from 1919 until 1924 and from 1939 until 1948. He served in the First World War and as a British field marshal [1] in the Second World War.

For most of his public life, Smuts, like many other native South Africans of white Afrikaner heritage, advocated segregation between the races and was opposed to the unilateral enfranchisement of the black majority in South Africa, fearing that would lead to the ultimate destruction of Western civilization in the nation.[2] However, in 1948 the Smuts government issued the Fagan Report, which stated that complete racial segregation in South Africa was not practicable and that restrictions on African migration into urban areas should be abolished. In this, the government was opposed by a majority of Afrikaners under the political leadership of the National Party who wished to deepen segregation and formalise it into a system of apartheid. This opposition contributed to his narrow loss in the 1948 general election.

He led commandos in the Second Boer War for the Transvaal. During World War I, he led the armies of South Africa against Germany, capturing German South-West Africa and commanding the British Army in East Africa. From 1917 to 1919, he was also one of five members of the British War Cabinet, helping to create the Royal Air Force. He became a field marshal in the British Army in 1941, and served in the Imperial War Cabinet under Winston Churchill. He was the only person to sign the peace treaties ending both the First and Second World Wars.

One of his greatest international accomplishments was the establishment of the League of Nations, the exact design and implementation of which relied upon Smuts.[3] He later urged the formation of a new international organisation for peace: the United Nations. Smuts wrote the preamble to the United Nations Charter, and was the only person to sign the charters of both the League of Nations and the UN. He sought to redefine the relationship between the United Kingdom and her colonies, by establishing the British Commonwealth, as it was known at the time. However, in 1946 the Smuts government was strongly condemned by a large majority in the United Nations Assembly for its discriminatory racial policies.

In 2004 he was named by voters in a poll held by the South African Broadcasting Corporation as one of the top ten Greatest South Africans of all time. The final positions of the top ten were to be decided by a second round of voting, but the programme was taken off the air due to political controversy, and Nelson Mandela was given the number one spot based on the first round of voting. In the first round, Jan Smuts came sixth.

| The life of Jan Smuts |

|---|

| Early life 1870 - 1895 |

| Transvaal 1895 - 1899 |

| Boer War 1899 - 1902 |

| British Transvaal 1902 - 1910 |

| The Old Boers 1910 - 1914 |

Contents |

Early life

He was born on 24 May 1870, at the family farm, Bovenplaats, near Malmesbury, in the Cape Colony. His family were prosperous, traditional Afrikaner farmers, long established and highly respected.

Jan was quiet and delicate as a child, strongly inclined towards solitary pursuits. During his childhood, he often went out alone, exploring the surrounding countryside; this awakened a passion for nature, which he retained throughout his life.

As the second son of the family, rural custom dictated that he would remain working on the farm; a full formal education was typically the preserve of the first son. However, in 1882, when Jan was twelve, his elder brother died, and Jan was sent to school in his brother's place. Jan attended the school in nearby Riebeek West. He made excellent progress here, despite his late start, and caught up with his contemporaries within four years. He moved on to Victoria College, Stellenbosch, in 1886, at the age of sixteen.

At Stellenbosch, he learned High Dutch, German, and Ancient Greek, and immersed himself further in literature, the classics, and Bible studies. His deeply traditional upbringing and serious outlook led to social isolation from his peers. However, he made outstanding academic progress, graduating in 1891 with double First-class honours in Literature and Science. During his last years at Stellenbosch, Smuts began to cast off some of his shyness and reserve, and it was at this time that he met Isie Krige, whom he was later to marry.

On graduation from Victoria College, Smuts won the Ebden scholarship for overseas study. He decided to travel to the United Kingdom to read law at Christ's College, Cambridge. Smuts found it difficult to settle at Cambridge; he felt homesick and isolated by his age and different upbringing from the English undergraduates. Worries over money also contributed to his unhappiness, as his scholarship was insufficient to cover his university expenses. He confided these worries to a friend from Victoria College, Professor JI Marais. In reply, Professor Marais enclosed a cheque for a substantial sum, by way of loan, urging Smuts not to hesitate to approach him should he ever find himself in need.[4] Thanks to Marais, Smuts's financial standing was secure. He gradually began to enter more into the social aspects of the university, although he retained his single-minded dedication to his studies.

During his time in Cambridge, he found time to study a diverse number of subjects in addition to law; he wrote a book, Walt Whitman: A Study in the Evolution of Personality, although it was unpublished. The thoughts behind this book laid the foundation for Smuts' later wide-ranging philosophy of holism.

Smuts graduated in 1893 with a double First. Over the previous two years, he had been the recipient of numerous academic prizes and accolades, including the coveted George Long prize in Roman Law and Jurisprudence.[5] One of his tutors, Professor Maitland, described Smuts as the most brilliant student he had ever met.[6] Lord Todd, the Master of Christ's College said in 1970 that "in 500 years of the College's history, of all its members, past and present, three had been truly outstanding: John Milton, Charles Darwin and Jan Smuts" [7]

In 1894, Smuts passed the examinations for the Inns of Court, entering the Middle Temple. His old college, Christ's College, offered him a fellowship in Law. However, Smuts turned his back on a potentially distinguished legal future.[8] By June 1895, he had returned to the Cape Colony, determined that he should make his future there.

Climbing the ladder

Smuts began to practice law in Cape Town, but his abrasive nature made him few friends. Finding little financial success in the law, he began to divert more and more of his time to politics and journalism, writing for the Cape Times. Smuts was intrigued by the prospect of a united South Africa, and joined the Afrikaner Bond. By good fortune, Smuts’ father knew the leader of the group, Jan Hofmeyr; Hofmeyr recommended Jan to Cecil Rhodes, who owned the De Beers mining company. In 1895, Rhodes hired Smuts as his personal legal advisor, a role that found the youngster much criticized by the hostile Afrikaans press. Regardless, Smuts trusted Rhodes implicitly.

When Rhodes launched the Jameson Raid, in the summer of 1895-6, Smuts was outraged. Betrayed by his employer, friend, and political ally, he resigned from De Beers, and disappeared from public life. Seeing no future for him in Cape Town, he decided to move to Johannesburg in August 1896. However, he was disgusted by what appeared to be a gin-soaked mining camp, and his new law practice could attract little business in such an environment. Smuts sought refuge in the capital of the South African Republic, Pretoria.

Through 1896, Smuts’ politics were turned on their head. He was transformed from being Rhodes’ most ardent supporter to being the most fervent opponent of British expansion. Through late 1896 and 1897, Smuts toured South Africa, furiously condemning the United Kingdom, Rhodes, and anyone opposed to the Transvaal President, the autocratic Paul Kruger.

In April 1897, he married Isie Krige of Cape Town. Professor JI Marais, Smuts’s benefactor at Cambridge, presided over the ceremony. Twins were born to the pair in March 1898, but unfortunately survived only a few weeks.

Kruger was opposed by many liberal elements in South Africa, and, when, in June 1898, Kruger fired the Transvaal Chief Justice, his long-term political rival John Gilbert Kotzé, most lawyers were up in arms. Recognising the opportunity, Smuts wrote a legal thesis in support of Kruger, who rewarded Smuts as State Attorney. In this capacity, he tore into the establishment, firing those he deemed to be illiberal, old-fashioned, or corrupt. His efforts to rejuvenate the republic polarised Afrikaners.

After the Jameson Raid, relations between the British and the Afrikaners had deteriorated steadily. By 1898, war seemed imminent. Orange Free State President Martinus Steyn called for a peace conference at Bloemfontein to settle each side’s grievances. With an intimate knowledge of the British, Smuts took control of the Transvaal delegation. Sir Alfred Milner, head of the British delegation, took exception to his dominance, and conflict between the two led to the collapse of the conference, consigning South Africa to war.

The Boer War

On 11 October 1899, the Boer republics invaded the British South African colonies, beginning the Second Boer War. In the early stages of the conflict, Smuts served as Kruger’s eyes and ears, handling propaganda, logistics, communication with generals and diplomats, and anything else that was required.

In the second phase of the war, Smuts served under Koos de la Rey, who commanded 500 commandos in the Western Transvaal. Smuts excelled at hit-and-run warfare, and the unit evaded and harassed a British army forty times its size. President Kruger and the deputation in Europe thought that there was good hope for their cause in the Cape Colony. They decided to send General de la Rey there to assume supreme command, but then decided to act more cautiously when they realized that General de la Rey could hardly be spared in the Western Transvaal.

Consequently, Smuts left with a small force of 300 men while another 100 men followed him. By this point in the war, the British scorched earth policy left little grazing land. One hundred of the cavalry that had joined Smuts were therefore too weak to continue and so Smuts had to leave these men with General Kritzinger. With few exceptions, Smuts met all the commandos in the Cape Colony and found between 1,400–1,500 men under arms, and not the 3,000 men as had been reported. By the time of the peace Conference in May 1902 there were 3,300 men operating in the Cape Colony. Although the people were enthusiastic for a general rising, there was a great shortage of horses (the Boers were an entirely mounted force) as they had been taken by the British. There was an absence of grass and wheat, which meant that he was forced to refuse nine tenths of those who were willing to join. The Boer forces raided supply lines and farms, spread Afrikaner propaganda, and intimidated those that opposed them, but they never succeeded in causing a revolt against the government. This raid was to prove one of the most influential military adventures of the 20th century and had a direct influence on the creation of the British Commandos and all the other special forces which followed. With these practical developments came the development of the military doctrines of deep penetration raids, asymmetric warfare and, more recently, elements of fourth generation warfare.

To end the conflict, Smuts sought to take a major target, the copper-mining town of Okiep. With a full assault impossible, Smuts packed a train full of explosives, and tried to push it downhill, into the town, where it would bring the enemy garrison to its knees. Although this failed, Smuts had proven his point: that he would stop at nothing to defeat his enemies. Combined with their failure to pacify the Transvaal, Smuts' success left the United Kingdom with no choice but to offer a ceasefire and a peace conference, to be held at Vereeniging.

Before the conference, Smuts met Lord Kitchener at Kroonstad station, where they discussed the proposed terms of surrender. Smuts then took a leading role in the negotiations between the representatives from all of the commandos from the Orange Free State and the South African Republic (15-31 May 1902). Although he admitted that, from a purely military perspective, the war could continue, he stressed the importance of not sacrificing the Afrikaner people for that independence. He was very conscious that 'more than 20,000 women and children have already died in the concentration camps of the enemy'. He felt it would have been a crime to continue the war without the assurance of help from elsewhere and declared, "Comrades, we decided to stand to the bitter end. Let us now, like men, admit that that end has come for us, come in a more bitter shape than we ever thought." His opinions were representative of the conference, which then voted by 54 to 6 in favour of peace. Representatives of the Governments met Lord Kitchener and at five minutes past eleven on 31 May 1902, Acting President Burger signed the Peace Treaty, followed by the members of his Government, Acting President de Wet and the members of his Government.

A British Transvaal

For all Smuts' exploits as a general and a negotiator, nothing could mask the fact that the Afrikaners had been defeated and humiliated. Lord Milner had full control of all South African affairs, and established an Anglophone elite, known as Milner's Kindergarten. As an Afrikaner, Smuts was excluded. Defeated but not deterred, in January 1905, he decided to join with the other former Transvaal generals to form a political party, Het Volk (People's Party), to fight for the Afrikaner cause. Louis Botha was elected leader, and Smuts his deputy.

When his term of office expired, Milner was replaced as High Commissioner by the more conciliatory Lord Selborne. Smuts saw an opportunity and pounced, urging Botha to persuade the Liberals to support Het Volk’s cause. When the Conservative government under Arthur Balfour collapsed, in December 1905, the decision paid off. Smuts joined Botha in London, and sought to negotiate full self-government for the Transvaal within British South Africa. Using the thorny political issue of Asian labourers ('coolies'), the South Africans convinced Prime Minister Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman and, with him, the cabinet and Parliament.

Through 1906, Smuts worked on the new constitution for the Transvaal, and, in December 1906, elections were held for the Transvaal parliament. Despite being shy and reserved, unlike the showman Botha, Smuts won a comfortable victory in the Wonderboom constituency, near Pretoria. His victory was one of many, with Het Volk winning in a landslide and Botha forming the government. To reward his loyalty and efforts, Smuts was given two key cabinet positions: Colonial Secretary and Education Secretary.

Smuts proved to be an effective leader, if unpopular. As Education Secretary, he had fights with the Dutch Reformed Church, of which he had once been a dedicated member, who demanded Calvinist teachings in schools. As Colonial Secretary, he was forced to confront Asian workers, the very people whose plight he had exploited in London, led by Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. Despite Smuts’ unpopularity, South Africa's economy continued to boom, and Smuts cemented his place as the Afrikaners’ brightest star.

During the years of Transvaal self-government, no-one could avoid the predominant political debate of the day: South African unification. Ever since the British victory in the war, it was an inevitability, but it remained up to the South Africans to decide what sort of country would be formed, and how it would be formed. Smuts favoured a unitary state, with power centralised in Pretoria, with English as the only official language, and with a more inclusive electorate. To impress upon his compatriots his vision, he called a constitutional convention in Durban, in October 1908.

There, Smuts was up against a hard-talking Orange delegation, who refused every one of Smuts' demands. Smuts had successfully predicted this opposition, and their objections, and tailored his own ambitions appropriately. He allowed compromise on the location of the capital, on the official language, and on suffrage, but he refused to budge on the fundamental structure of government. As the convention drew into autumn, the Orange leaders began to see a final compromise as necessary to secure the concessions that Smuts had already made. They agreed to Smuts’ draft South African constitution, which was duly ratified by the South African colonies. Smuts and Botha took the constitution to London, where it was passed by Parliament, and signed into law by Edward VII in December 1909. Smuts' dream had been realised.

The Old Boers

The Union of South Africa was born, and the Afrikaners held the key to political power, for they formed the largest part of the electorate. Although Botha was appointed Prime Minister of the new country, Smuts was given three key ministries: those for the Interior, the Mines, and Defence. Undeniably, Smuts was the second most powerful man in South Africa. To solidify their dominance of South African politics, the Afrikaners united to form the South African Party, a new pan-South African Afrikaner party.

The harmony and cooperation soon ended. Smuts was criticised for his over-arching powers, and was reshuffled, losing his positions in charge of Defence and the Mines, but gaining control of the Treasury. This was still too much for Smuts' opponents, who decried his possession of both Defence and Finance: two departments that were usually at loggerheads. At the 1913 South African Party conference, the Old Boers, of Hertzog, Steyn, and De Wet, called for Botha and Smuts to step down. The two narrowly survived a conference vote, and the troublesome triumvirate stormed out, leaving the party for good.

With the schism in internal party politics came a new threat to the mines that brought South Africa its wealth. A small-scale miners' dispute flared into a full-blown strike, and rioting broke out in Johannesburg after Smuts intervened heavy-handedly. After police shot dead twenty-one strikers, Smuts and Botha headed unaccompanied to Johannesburg to personally resolve the situation. They did, facing down threats to their own lives, and successfully negotiating a cease-fire.

The cease-fire did not hold, and, in 1914, a railway strike turned into a general strike, and threats of a revolution caused Smuts to declare martial law. Smuts acted ruthlessly, deporting union leaders without trial and using Parliament to retrospectively absolve him or the government of any blame. This was too much for the Old Boers, who set up their own party, the National Party, to fight the all-powerful Botha-Smuts partnership. The Old Boers urged Smuts' opponents to arm themselves, and civil war seemed inevitable before the end of 1914. In October 1914, when the Government was faced with open rebellion by Lt Col Manie Maritz and others in the Maritz Rebellion, Government forces under the command of Botha and Smuts were able to put down the rebellion without it ever seriously threatening to ignite into a Third Boer War.

Soldier, statesman, and scholar

During World War I, Smuts formed the South African Defence Force. His first task was to suppress the Maritz Rebellion, which was accomplished by November 1914. Next he and Louis Botha led the South African army into German South West Africa and conquered it (see the South-West Africa Campaign for details). In 1916 General Smuts was put in charge of the conquest of German East Africa. While the East African Campaign went fairly well, the German forces were not destroyed. However, early in 1917 he was invited to join the Imperial War Cabinet by David Lloyd George, so he left the area and went to London. In 1918, Smuts helped to create a Royal Air Force, independent of the army.

Smuts and Botha were key negotiators at the Paris Peace Conference. Both were in favour of reconciliation with Germany and limited reparations. Smuts advocated a powerful League of Nations, which failed to materialise. The Treaty of Versailles gave South Africa a Class C mandate over German South West Africa (which later became Namibia), which was occupied from 1919 until withdrawal in 1990. At the same time, Australia was given a similar mandate over German New Guinea, which it held until 1975. Both Smuts and the Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes feared the rising power of Japan in the post First World War world.

Smuts returned to South African politics after the conference. When Botha died in 1919, Smuts was elected Prime Minister, serving until a shocking defeat in 1924 at the hands of the National Party.

While in England for an Imperial Conference in June 1920, Smuts went to Ireland and met Eamon De Valera to help broker an armistice and peace deal between the warring English and Irish nationalists. Smuts attempted to sell the concept of Ireland receiving Dominion status similar to that of Australia and South Africa.[9]

While in academia, Smuts pioneered the concept of holism, defined as "the tendency in nature to form wholes that are greater than the sum of the parts through creative evolution" in his 1926 book, Holism and Evolution. One biographer ties together his far-reaching political vision with his technical philosophy:

It had very much in common with his philosophy of life as subsequently developed and embodied in his Holism and Evolution. Small units must needs develop into bigger wholes, and they in their turn again must grow into larger and ever-larger structures without cessation. Advancement lay along that path. Thus the unification of the four provinces in the Union of South Africa, the idea of the British Commonwealth of Nations, and, finally, the great whole resulting from the combination of the peoples of the earth in a great league of nations were but a logical progression consistent with his philosophical tenets.

After Einstein studied "Holism and Evolution" soon upon its publication, he wrote that two mental constructs will direct human thinking in the next millennium, his own mental construct of relativity and Smuts' of holism. In the work of Smuts he saw a clear blueprint of much of his own life, work and personality. Einstein also said of Smuts that he was "one of only eleven men in the world" who conceptually understood his Theory of Relativity [10][11]

As a botanist, Smuts collected plants extensively over southern Africa. He went on several botanical expeditions in the 1920s and 1930s with John Hutchinson, former Botanist in charge of the African section of the Herbarium of the Royal Botanic Gardens and taxonomist of note.

Smuts and segregation

Although at times hailed as a liberal, Smuts is often depicted as a white supremacist who played an important role in establishing and supporting a racially segregated society in South Africa.[12] While he thought it was the duty of whites to deal justly with Africans and raise them up in civilization, they should not be given political power.[13] Giving the right to vote to the black African majority he feared would imply the ultimate destruction of Western civilization in South Africa.[14]

Smuts was for most of his political life a vocal supporter of segregation of the races, and in 1929 he justified the erection of separate institutions for blacks and whites in tones reminiscent of the later practice of apartheid:

| “ | The old practice mixed up black with white in the same institutions, and nothing else was possible after the native institutions and traditions had been carelessly or deliberately destroyed. But in the new plan there will be what is called in South Africa "segregation" — separate institutions for the two elements of the population living in their own separate areas. Separate institutions involve territorial segregation of the white and black. If they live mixed together it is not practicable to sort them out under separate institutions of their own. Institutional segregation carries with it territorial segregation.[15] | ” |

In general, Smuts' view of Africans was patronising, he saw them as immature human beings that needed the guidance of whites, an attitude that reflected the common perceptions of the white minority population of South Africa in his life time. Of Africans he stated that:

| “ | These children of nature have not the inner toughness and persistence of the European, not those social and moral incentives to progress which have built up European civilization in a comparatively short period.[16] | ” |

Smuts is often accused of being a politician who extolled the virtues of humanitarianism and liberalism abroad while failing to practice what he preached at home in South Africa.[17] This was most clearly illustrated when India, in 1946, made a formal complaint in the United Nations concerning the legalised racial discrimination against Indians in South Africa. Appearing personally before the United Nations General Assembly, Smuts defended the racial policies of his government by fervently pleading that India's complaint was a matter of domestic jurisdiction. However, the General Assembly condemned South Africa for its racial policies by the requisite two-thirds majority and called upon the Smuts government to bring its treatment of the South African Indians in conformity with the basic principles of the United Nations Charter.[18]

At the same conference, the African National Congress President General Alfred Bitini Xuma along with delegates of the South African Indian Congress brought up the issue of the brutality of Smut's police regime against the African Mine Workers' Strike earlier that year as well as the wider struggle for equality in South Africa. [19]

The international criticism of racial discrimination in South Africa led Smuts to modify his rhetoric around segregation. In a bid to make South African racial policies sound more acceptable to Britain he declared already in 1942 that "segregation had failed to solve the Native problem of Africa and that the concept of trusteeship offered the only prospect of happy relations between European and African".[20]

In 1948 he went further away from his previous views on segregation when supporting the recommendations of the Fagan Commission that Africans should be recognized as permanent residents of White South Africa and not only temporary workers that really belonged in the reserves.[21] This was in direct opposition to the policies of the National Party that wished to extend segregation and formalise it into apartheid.

There is however no evidence that Smuts ever supported the idea of equal political rights for blacks and whites. The Fagan Commission did not advocate the establishment of a non-racial democracy in South Africa, but rather wanted to liberalise influx controls of Africans into urban areas in order to facilitate the supply of African labour to the South African industry. It also envisaged a relaxation of the pass laws that had restricted the movement of Africans in general.[22] The commission was at the same time unequivocal about the continuation of white political privilege, it stated that "In South Africa, we the White men, cannot leave and cannot accept the fate of a subject race".[23]

Second World War

After nine years in opposition and academia, Smuts returned as Deputy Prime Minister in a 'grand coalition' government under Barry Hertzog. When Hertzog advocated neutrality towards Nazi Germany in 1939, he was deposed by a party caucus, and Smuts became Prime Minister for the second time. He had served with Winston Churchill in World War I, and had developed a personal and professional rapport. Smuts was invited to the Imperial War Cabinet in 1939 as the most senior South African in favour of war. On 28 May 1941 Smuts was appointed a field marshal of the British Army, becoming the first South African to hold that rank.

Smuts' importance to the Imperial war effort was emphasised by a quite audacious plan, proposed as early as 1940, to appoint Smuts as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, should Churchill die or otherwise become incapacitated during the war. This idea was put by Sir John Colville, Churchill's private secretary, to Queen Mary and then to George VI, both of whom warmed to the idea. [24] As Churchill lived for another twenty-five years, the plan was never put into effect and its constitutionality was never tested. This closeness to the British establishment, to the King, and to Churchill made Smuts very unpopular amongst the Afrikaner, leading to his eventual downfall.

In May 1945, he represented South Africa in San Francisco at the drafting of the United Nations Charter. Just as he did in 1919, Smuts urged the delegates to create a powerful international body to preserve peace; he was determined that, unlike the League of Nations, the United Nations would have teeth. Smuts signed the Paris Peace Treaty, resolving the peace in Europe, thus becoming the only signatory of both the treaty ending World War I, and that ending the Second.

After the war

His preoccupation with the war had severe political repercussions in South Africa. Smuts's support of the war and his support for the Fagan Commission made him unpopular amongst the Afrikaners and Daniel François Malan's pro-Apartheid stance won the National Party the 1948 general election. Although this result was widely forecast, it is a credit to Smuts's political acumen that he was only narrowly defeated (and, in fact, won the popular vote). Smuts, who had been confident of victory, lost his own seat and retired from politics. He still hoped that the tenuous National Party government would fall; but it was to remain in power until 1990, when after four decades of Apartheid, a transitional government of national unity was formed.

Smuts's inauguration as chancellor of Cambridge University shortly after the election restored his morale, but the sudden and unexpected death of his eldest son, Japie, in October 1948 brought him to the depths of despair. In the last two years of his life, now frail and visibly aged, Smuts continued to comment perceptively, and on occasion presciently, on world affairs. Europe and the Commonwealth remained his dominant concerns. He regretted the departure of the Irish republic from the Commonwealth, but was unhappy when India remained within it after it became a republic, fearing the example this would set South Africa's Nationalists. His outstanding contributions as a world statesman were acknowledged in innumerable honours and medals. At home his reputation was more mixed. Nevertheless, despite ill health he continued his public commitments.

On 29 May 1950, a week after the public celebration of his eightieth birthday in Johannesburg and Pretoria, he suffered a coronary thrombosis. He died of a subsequent attack on his family farm of Doornkloof, Irene, near Pretoria, on 11 September 1950, and was buried at Pretoria on 16 September.

Support for Zionism

South African supporters of Theodor Herzl contacted Smuts in 1916. Smuts, who supported the Balfour Declaration, met and became friends with Chaim Weizmann, the future President of Israel, in London. In 1943 Weizmann wrote to Smuts, detailing a plan to develop Britain's African colonies to compete with the United States. During his service as Premier, Smuts personally fundraised for multiple Zionist organizations.[25] His government granted de facto recognition to Israel on 24 May 1948 and de jure recognition on 14 May 1949.[26] However, Smuts was deputy prime minister when the Hertzog government in 1937 passed the Aliens Act that was aimed at preventing Jewish immigration to South Africa. The act was seen as a response to growing anti-Semitic sentiments among Afrikaners.[1]

He lobbied against the White Paper.[27]

Several streets and a kibbutz, Ramat Yohanan, in Israel are named after Smuts.[26]

Smuts' wrote an epitaph for Weizmann, describing him as the greatest Jew since Moses."[28]

Smuts once said:

| “ | Great as are the changes wrought by this war, the great world war of justice and freedom, I doubt whether any of these changes surpass in interest the liberation of Palestine and its recognition as the Home of Israel.[29] | ” |

Miscellaneous

In 1931, he became the first foreign President of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. In that year, he was also elected the second foreign Lord Rector of St Andrews University (after Fridtjof Nansen). In 1948, he was elected Chancellor of Cambridge University, becoming the first foreigner to hold that position. He held the position until his death.

He is remembered also for the coining of the terms holism and holistic: abstractions not unnaturally linked to his political concerns. The earliest recorded use of the word apartheid is also attributed to him, from a 1917 speech.

After the death of Woodrow Wilson and the implementation of the Treaty of Versailles, Smuts uttered the words that perhaps best defined the Treaty negotiations "Not Wilson, but humanity failed at Paris."

Smuts was an amateur botanist, and a number of South African plants are named after him.

The international airport serving Johannesburg was known as 'Jan Smuts Airport' from its construction in 1952 until 1994. In 1994, it was renamed to 'Johannesburg International Airport' to remove any political connotations. In 2006, it was renamed again (re-attaching political connotation), to 'Oliver Tambo International Airport'. The South African government has yet to explain the reversal of policy, now allowing facilities to be named after political figures, and thereby fuelling the perception of a policy of eradicating the history or memory of the South African white population. Several major thoroughfares in South African cities named after Jan Smuts and other white historical figures are scheduled to be renamed to honour African National Congress historical figures.

Residences at the University of Cape Town and at Rhodes University are named after him, as is the Law Faculty building at the University of the Witwatersrand.

The Libertines recorded a song titled General Smuts in reference to a pub named after him located in Bloemfontein Road, Shepherds Bush, London, close to QPR football club. It appeared as a B-side to their single Time for Heroes.

In the television programme, Young Indiana Jones, the protagonist at a period in World War I in East Africa encounters a group of superb soldiers, one of whom is a General with more than a passing resemblance and character (though not the name) of Smuts, particularly during engagements with Letto von Griem in East Africa.

In 1932, the kibbutz Ramat Yohanan in Israel was named after him. Smuts was a vocal proponent of the creation of a Jewish state, and spoke out against the rising anti-Semitism of the 1930s.[30]

Smuts is played by South African playwright Athol Fugard in the 1982 film Gandhi.

Wilbur Smith refers to and portrays Jan Smuts in several of his South Africa based novels including When the Lion Feeds, The Sound of Thunder, A Sparrow Falls, Power of the Sword and Rage. Smuts is often referred to as "Slim (Clever) Jannie" or Oubaas (Old Boss) as well as by his proper names.

Honours

Awards/decorations

- Privy Councillor

- Order of Merit

- Companion of Honour

- Dekoratie voor Trouwe Dienst

- Efficiency Decoration

- King's Counsel

- Fellow of the Royal Society

- Bencher of the Middle Temple

- Albert Medal

Medals, Commonwealth and South African

- Boer War Medal

- 1914-15 Star

- Victory Medal

- General Service Medal

- King George V's Jubilee Medal

- King George VI's Coronation Medal

- Africa Star

- Italy Star

- France and Germany Star

- Defence Medal

- War Medal 1939–1945

- Africa Service Medal

Foreign decorations and medals

- Service Medal (Mediterranean Area) (USA)

- Order of the Tower and Sword for Valour, Loyalty and Merit (Portugal)

- Grootkruis van de Orde van de Nederlandsche Leeuw (Netherlands)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of Mohamed Ali (Egypt)

- Grand Cross of the Order of the Redeemer (Greece)

- Grand Cross of the Order of Léopold (Belgium)

- Croix de guerre (Belgium)

- Légion d'honneur Croix de Commandeur (France)

- La Grand Croix de l'Ordre de L'Etoile Africane (Belgium)

- King Christian X Frihedsmedaille (Denmark)

- Aristion Andrias (Greece)

- Woodrow Wilson Peace Medal

See also

- Military history of South Africa

- When Smuts Goes

- History of Kenya - Colonial History

- History of Tanzania - First Word War

| Jan Smuts |  |

|---|---|

| I: Early life | II: The South African Republic | III: The Boer War | IV: A British Transvaal V: The Old Boers |

Footnotes

- ↑ http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-6721/Jan-Smuts "Prime Minister Lloyd George at once recognized his abilities and made him minister of air. From then on he was used in a variety of tasks. He organized the Royal Air Force and was concerned in all major decisions about the war."

- ↑ http://www.jstor.org/view/00028762/di951453/95p01174/0

- ↑ Crafford p. 141

- ↑ Letter from Marais to Smuts, 8 Aug 1892; Hancock et al (1966-73): vol. 1, p. 25

- ↑ Smuts (1952), p. 23

- ↑ Letter from Maitland to Smuts, 15 June 1894; Hancock et al (1966-73): vol. 1, pp. 33-34

- ↑ Jan Smuts - Memoirs of the Boer War (1994) Introduction, p. 19

- ↑ Smuts (1952), p. 24

- ↑ J.C. Smuts, J. C. Smuts, 1952, p. 252

- ↑ Jan Smuts - Memoirs of the Boer War (1994) Introduction p.19

- ↑ Crafford p. 140

- ↑ http://www.jstor.org/view/00218537/ap010126/01a00120/1

- ↑ http://www.sahistory.org.za/pages/people/bios/smuts-j.htm

- ↑ http://www.jstor.org/view/00028762/di951453/95p01174/0

- ↑ http://www.jhered.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/21/5/225.pdf

- ↑ http://www.jhered.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/21/5/225.pdf

- ↑ http://www.jstor.org/view/00218537/ap010126/01a00120/1

- ↑ http://www.sacp.org.za/docs/history/dadoo-38.html

- ↑ http://www.anc.org.za/ancdocs/history/misc/miners.html

- ↑ http://www.queensu.ca/sarc/Conferences/1940s/Henshaw.htm THE AFRICAN MINERS' STRIKE OF 1946 by M. P. Naicker - accessed 16/10/08

- ↑ http://www.sahistory.org.za/pages/people/bios/smuts-j.htm

- ↑ http://africanhistory.about.com/od/apartheidterms/g/def_Fagan.htm

- ↑ http://www.jstor.org/view/0022278x/ap010064/01a00170/0

- ↑ Colville, Sir John: The Fringes of Power, pages 269-271 (ISBN 1-84212-626-1)

- ↑ Jane Hunter and Jane Haapiseva-Hunter. Israeli Foreign Policy: South Africa and Central America, 1987. Pages 21-22.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Beit-Hallahmi, Benjamin. The Israeli Connection: Whom Israel Arms and Why, 1988. Page 109-111.

- ↑ Howard Stafford Crossman, Richard. A Nation Reborn: A Personal Report on the Roles Played by Weizmann, Bevin and Ben-Gurion in the story of Israel, 1960. Page 76.

- ↑ Lockyer, Norman. Nature, digitized 5 February 2007. Nature Publishing Group.

- ↑ S. Klieman, Aaron. The Rise of Israel, 1987. Page 16.

- ↑ "Jewish American Year Book 5695" (PDF). Jewish Publication Society of America (1934). Retrieved on 2006-08-12.. Tel Aviv and several other Israeli cities have a Jan Smuts Street.

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Hancock, WK and van der Poel, J (eds) - Selections from the Smuts Papers, 1886-1950, (7 vols), (1966-73)

- Spies, SB and Natrass, G (eds) - Jan Smuts – Memoirs of the Boer War Jonathan Ball, Johannesburg 1994

Secondary sources

- Armstrong, HC - Grey Steel: A Study of Arrogance, (1939), ASIN B00087SNP4)

- Clark, NL - South Africa: The Rise and Fall of Apartheid, (2004), (ISBN 0 582 41437 7)

- Crafford, FS - Jan Smuts: A Biography, (1943), ISBN 1417992905

- Friedman, B - Smuts: A Reappraisal, (1975)

- Geyser, O - Jan Smuts and His International Contemporaries, (2002), (ISBN 1-919874-10-0)

- Hancock, WK - Smuts: 1. The Sanguine Years, 1870—1919, (1962)

- Hancock, WK - Smuts: 2. Fields of Force, 1919-1950, (1968)

- Hutchinson, John - A Botanist in Southern Africa, (1946), PR Gawthorn Ltd.

- Ingham, K - Jan Christian Smuts: The Conscience of a South African, (1986)

- Millin, SG - General Smuts, (2 vols), (1933)

- Reitz, D - Commando: A Boer Journal of the Boer War, (ISBN 0-9627613-3-8)

- Smuts, JC - Jan Christian Smuts, (1952), e-book (ISBN 978-1-920091-29-3)

External links

- "Revisiting Urban African Policy and the Reforms of the Smuts Government, 1939-48", by Gary Baines

- Africa And Some World Problems by Jan Smuts at archive.org

- Holism And Evolution by Jan Smuts

- The White man's task by Jan Smuts

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by New office |

Minister for the Interior 1910 – 1912 |

Succeeded by Abraham Fischer |

| Preceded by New office |

Minister for Defence (first time) 1910 – 1920 |

Succeeded by Hendrick Mentz |

| Preceded by Henry Charles Hull |

Minister for Finance 1912 – 1915 |

Succeeded by Sir David Pieter de Villiers Graaff |

| Preceded by Louis Botha |

Prime Minister (first time) 1919 – 1924 |

Succeeded by James Barry Munnik Hertzog |

| Preceded by Oswald Pirow |

Minister for Justice 1933 – 1939 |

Succeeded by Colin Fraser Steyn |

| Preceded by James Barry Munnik Hertzog |

Prime Minister (second time) 1939 – 1948 |

Succeeded by Daniel François Malan |

| Preceded by Oswald Pirow |

Minister for Defence (second time) 1939 – 1948 |

Succeeded by Frans Erasmus |

| Preceded by James Barry Munnik Hertzog |

Minister for Foreign Affairs 1939 – 1948 |

Succeeded by Daniel François Malan |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by Louis Botha |

Leader of the South African Party 1919 – 1934 |

SAP Merged into United Party |

| Preceded by James Barry Munnik Hertzog |

Leader of the United Party 1939 – 1950 |

Succeeded by Jacobus Gideon Nel Strauss |

| Academic offices | ||

| Preceded by Sir Wilfred Grenfell |

Rector of the University of St Andrews 1931 – 1934 |

Succeeded by Guglielmo Marconi |

| Preceded by Stanley Baldwin |

Chancellor of the University of Cambridge 1948 – 1950 |

Succeeded by The Lord Tedder |

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Smuts, Jan Christian |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 24 May 1870 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Bovenplaats, near Malmesbury, Western Cape, Cape Colony |

| DATE OF DEATH | 11 September 1950 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Doornkloof, Irene, Gauteng, near Pretoria, South Africa |