Jabberwocky

"Jabberwocky" is a poem of nonsense verse written by Lewis Carroll, originally featured as a part of his novel Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There (1871). It is considered by many to be one of the greatest nonsense poems written in the English language.[1] The poem is sometimes used in primary schools to teach students about the use of portmanteau and nonsense words in poetry, as well as use of nouns and verbs.[2]

Contents |

The poem

'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

"Beware the Jabberwock, my son!

The jaws that bite, the claws that catch!

Beware the Jubjub bird, and shun

The frumious Bandersnatch!"

He took his vorpal sword in hand:

Long time the manxome foe he sought—

So rested he by the Tumtum tree,

And stood awhile in thought.

And as in uffish thought he stood,

The Jabberwock, with eyes of flame,

Came whiffling through the tulgey wood,

And burbled as it came!

One, two! One, two! and through and through

The vorpal blade went snicker-snack!

He left it dead, and with its head

He went galumphing back.

"And hast thou slain the Jabberwock?

Come to my arms, my beamish boy!

O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay!"

He chortled in his joy.

'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

Glossary

The first verse originally appeared in Mischmasch—a periodical which Carroll wrote and edited for the amusement of his family—claiming to be a piece of Anglo-Saxon poetry.

Several of the words in the poem are of Carroll's own invention, many of them portmanteaux. In the book, the character of Humpty Dumpty gives definitions for the nonsense words in the first stanza. In later writings, Lewis Carroll explained several of the others. The rest of the nonsense words were never explicitly defined by Carroll, who claimed that he did not know what some of them meant. An extended analysis of the poem is given in the book The Annotated Alice, including writings from Carroll about how he formed some of his idiosyncratic words. A few words that Carroll invented in this poem (namely "chortled" and "galumphing") have entered the English language. The word jabberwocky itself is sometimes used to refer to nonsense language.

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

- Bandersnatch – A swift moving creature with snapping jaws, capable of extending its neck.[3]

- Borogove – A thin shabby-looking bird with its feathers sticking out all round, "something like a live mop".[4] The initial syllable of borogove is pronounced as in borrow, rather than as in burrow.[5].

- Burbled – Possibly a mixture of "bleat", "murmur", and "warble".[7] Burble is also pre-existing word, circa 1303, meaning to form bubbles as in boiling water.

- Chortled - Combination of chuckle and snort.[4]

- Frabjous - Probably a blend of fair, fabulous, and joyous .[8]

- Frumious – Combination of "fuming" and "furious."[5]

- Galumphing - Perhaps a blend of "gallop" and "triumphant". Used to describe a way of "trotting" down hill, while keeping one foot further back than the other. This enables the Galumpher to stop quickly.[8]

- Gimble – To make holes as does a gimlet.[4]

- Gyre – To go round and round like a gyroscope.[4][9] However, Carroll also wrote in Mischmasch that it meant to scratch like a dog. The g is pronounced like the /g/ in gold, not like gem.[10].

- Jubjub – A desperate bird that lives in perpetual passion.[3]

- Manxome – Fearsome; the word is of unknown origin. [8]

- Mimsy – Combination of "miserable" and "flimsy".[4]

- Mome – Possibly short for "from home," meaning that the raths had lost their way.[4]

- Outgrabe (past tense; present tense outgribe) – Something between bellowing and whistling, with a kind of sneeze in the middle.[4][11]

- Rath – A sort of green pig.[4] (See Origin and structure for further details.)

- Tove – A combination of a badger, a lizard, and a corkscrew. They are very curious looking creatures which make their nests under sundials and eat only cheese.[4] Pronounced so as to rhyme with groves.[5] Note that "gyre and gimble," i.e. rotate and bore, is in reference to the toves being partly corkscrew by Humpty Dumpty's definitions.

- Tulgey - Thick, dense, dark.

- Uffish – A state of mind when the voice is gruffish, the manner roughish, and the temper huffish.[7]

- Vorpal - See vorpal sword.

- Wabe – The grass plot around a sundial. It is called a "wabe" because it goes a long way before it, and a long way behind it, and a long way beyond it on each side.[4]

Pronunciation

In the Preface to The Hunting of the Snark, Carroll wrote:

[Let] me take this opportunity of answering a question that has often been asked me, how to pronounce "slithy toves." The "i" in "slithy" is long, as in "writhe"; and "toves" is pronounced so as to rhyme with "groves." Again, the first "o" in "borogoves" is pronounced like the "o" in "borrow." I have heard people try to give it the sound of the "o" in "worry." Such is Human Perversity.

Also, in an author's note (dated Christmas 1896) about Through the Looking-Glass, Carroll wrote:

The new words, in the poem "Jabberwocky", have given rise to some differences of opinion as to their pronunciation: so it may be well to give instructions on that point also. Pronounce "slithy" as if it were the two words, "sly, thee": make the "g" hard in "gyre" and "gimble": and pronounce "rath" to rhyme with "bath."

Origin and structure

The poem was written during Lewis Carroll's stay with relatives at Whitburn, near Sunderland, although the first stanza was written in Croft on Tees, close to nearby Darlington, where Carroll lived as a boy.[12] The story may have been inspired by the local Sunderland area legend of the Lambton Worm, as noted in "A Town Like Alice's" by Michael Bute (1997 Heritage Publications, Sunderland) and as later adapted in "Alice in Sunderland" by Brian Talbot.

The first stanza of the poem originally appeared in Mischmasch, a periodical that Carroll wrote and illustrated for the amusement of his family. It was entitled "Stanza of Anglo-Saxon Poetry." Carroll also gave translations of some of the words which are different from Humpty Dumpty's. For example, a "rath" is described as a species of land turtle that lived on swallows and oysters. Also, "brillig" is spelled with two ys rather than with two is.

Roger Lancelyn Green, in the Times Literary Supplement (March 1, 1957), and later in The Lewis Carroll Handbook (1962), suggests that the rest of the poem may have been inspired by an old German ballad, "The Shepherd of the Giant Mountains". In this epic poem, "a young shepherd slays a monstrous Griffin". It was translated into English by Lewis Carroll's relative Menella Bute Smedley in 1846, many years before the appearance of the Alice books. English computer scientist and historian Sean B. Palmer notes a possible Shakespearean source.[13] The inspiration for the Jabberwock allegedly came from a tree in the gardens of Christ Church, Oxford, where Carroll was a mathematician under his right name of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson. The tree in question is large and ancient with many sprawling, twisted branches somewhat suggestive of tentacles, or of the Hydra of Greek mythology.

Although the poem contains many nonsensical words, its structure is perfectly consistent with classic English poetry. The sentence structure is accurate (another aspect that has been challenging to reproduce in other languages), the poetic forms are observed (e.g. quatrain verse, rhymed, iambic meter), and a "story" is somewhat discernible in the flow of events. According to Alice in Through the Looking-Glass, "Somehow it seems to fill my head with ideas – only I don't exactly know what they are!".

The narrative contained in the middle four verses of the poem may be considered as an example of the monomyth.

Translations

"Jabberwocky" has become famous around the world, with translations into many languages.[14] The task of translation is the more notable and difficult because many of the principal words of the poem were simply made up by Carroll, having had no previous meaning. Translators have generally dealt with these words by inventing words of their own. Sometimes these are similar in spelling or sound to Carroll's words while respecting the morphology of the language to be translated into. For example in Frank L. Warrin's French translation "'Twas brillig" is translated as "Il brilgue". In cases like this both the original and the invented words may echo actual words in the lexicon, but not necessarily ones with similar meanings. Translators have also invented words which draw on root words with meanings similar to the English roots used by Carroll. As Douglas Hofstadter has noted[15] the word "slithy" echoes English words including "slimy", "slither", "slippery", "lithe" and "sly". The same French translation uses "lubricilleux" for "slithy", evoking French words like "lubrifier" (to lubricate) to give a similar impression of the meaning of the invented word. It makes a great difference whether the poem is translated in isolation or as part of a translation of the novel. In the latter case the translator must, through Humpty Dumpty, supply explanations of the invented words in the first stanza.

Full translations of "Jabberwocky" into French and German can be found in Martin Gardner's The Annotated Alice along with a discussion of why some translation decisions were made.

Yuen Ren Chao, a Chinese linguist, translated "Jabberwocky" into Chinese[16] by inventing characters to imitate what Rob Gifford describes as the "slithy toves that gyred and gimbled in the wabe of Carroll's original".[17]

Reception of the poem

"Jabberwocky" was meant by Carroll as a parody designed to show how not to write a poem.[18] The poem has since transcended Carroll's purpose, becoming now the subject of serious study. This transformation of perception was in a large part predicted by G. K. Chesterton.[19] According to Chesterton and Green, among others, the original purpose of "Jabberwocky" was to satirize pretentious poetry and ignorant literary critics, but has itself been the subject of pedestrian translations and explanations as well as being incorporated into classroom learning. Chesterton wrote in 1932,

- "Poor, poor, little Alice! She has not only been caught and made to do lessons; she has been forced to inflict lessons on others".

In the following years, individuals have taken to analyzing Carroll's nonsense words and seriously interpreting his instructions on the "correct" pronunciation of these words.

The reach of the poem

"Jabberwocky" has been the source of countless parodies and tributes. In most cases the writers simply change the nonsense words into words relating to the parodied subject (e.g. Frank Jacobs's "Lewis Carroll as a TV Critic" in For Better or Verse). Other writers use the poem as a poetic form, much like a sonnet, and create their own nonsense words and glossaries (e.g. "Strunklemiss" by S. K. Azoulay).

Derivative works

- See also: Jabberwocky (disambiguation)

Since its creation, "Jabberwocky" has taken on some qualities of a folkloric myth or legend. The creatures and characters of the poem are often referenced or cited in popular culture, leading to many appearances in many media since its writing. Notable examples include:

Publishing

- In 1948, the Gaberbocchus Press was founded in London by Stefan and Franciszka Themerson, and named after the Latin word for 'Jabberwocky', from a later translation made by Lewis Carroll's uncle, Hassard Dodgson. In 31 years the Gaberbocchus Press published over sixty titles, including works by Alfred Jarry, Kurt Schwitters, Bertrand Russell and the Themersons themselves. Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi became one of the most celebrated plays and was published in many editions.

Literature

- In 1943, Henry Kuttner, writing with his wife C. L. Moore as Lewis Padgett, published a science fiction short story called Mimsy Were the Borogoves in the magazine Astounding, and has since been republished in several anthologies. It posits that the poem is actually a communication with hidden meaning from the future. The story was the inspiration for the 2007 film The Last Mimzy.

- In 1951, noted mystery writer Fredric Brown drew substantively on the poem for the comic mystery novel Night of the Jabberwock, in which the narrator learns that the Alice novels are not fiction but are an encoded report detailing the existence of another plane of reality.

- In 1962, in his short story "Naudsonce," H. Beam Piper used a blend of the first few lines from "Jabberwocky" and Robert W. Service's "The Shooting of Dan McGrew" as a demonstration to a newly encountered alien race that humans use a spoken language. The contact team member stood before the alien assemblage and solemnly intoned "'Twas brillig and the slithy toves were whooping it up in the Malemute Saloon, and the kid that handled the music box did gyre and gimble in the wabe, and back of the bar in a solo game all mimsy were the borogoves, and the mome raths outgrabe the lady that's known as Lou".

- Roger Zelazny's Chronicles of Amber series had a vivid scene where Luke has an acid trip and winds up in the poem and Merlin must save him.

- A character in the book Alien vs Predator: Hunter's Planet by David Bischoff and Stephani Perry, on numerous occasions remembers bits and pieces of the poem, first as a way to pass the time, then as a comparison to the grotesque form of the Xenomorph.

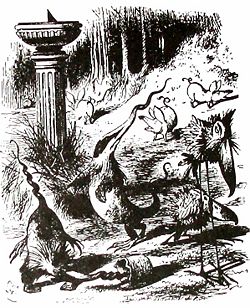

- Military science fiction author John Ringo has based a certain portion of his Space Bubble series of books around the Jabberwocky, partially in reference to the nonsensical nature of quantum physics that the characters end up dealing with. The first novel of the series was named Into the looking Glass as a number of the Higgs Boson portals within the book were named for Carroll's portal. The following books were named Vorpal Blade and Manxome Foe. The next book is due to be The Claws that Catch. The Jabberwock has a body like that of a dragon and its head is like that of an insect; an image probably inspired by the book's original illustration (see above).

- The poem is quoted in the book Dave at Night by Gail Carson Levine.

Film and TV

- In 1934, a Betty Boop short titled Betty in Blunderland was released featuring the Jabberwock as the antagonist.

- In the 1951 Disney version of Alice in Wonderland, the Cheshire Cat is heard singing the poem before he materializes in front of Alice.

- In 1971, film director Jan Švankmajer made a 14 minute short film called Jabberwocky (Žvahlav aneb šaticky Slaměného Huberta) which features the whole poem. As the poem is read out, various toys come to life, dancing around. The only thing that seems to stop the toys is a black cat that appears. This animation film is available on the DVD Cinema 16: European Short Films.

- In a 1976 episode of Saturday Night Live, host Desi Arnaz plays a character who recites the Jabberwocky poem and is so baffled by its language shouts "Who the hell talks like this?!", throws the book down and walks off stage muttering Spanish.

- In 1977, Terry Gilliam directed a movie called Jabberwocky. A poster for the movie featured a coloured version of the Jabberwocky illustration, and the first stanza of the poem is recited at the start of the film. The movie's plot very loosely resembles that of the poem.

- In 1985 a two-part telemovie was filmed of Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass; it featured the Jabberwock as the principal antagonist in the second part, pursuing Alice until she finds the courage to stand up to it.

- In 1995, the vampire-cop drama Forever Knight featured an episode called "Curiouser and Curiouser," where Nick enters a delusional world where everyone is opposite and his vampiric father LaCroix (Nigel Bennett) recites lines from the Carroll poetry. In the final confrontation, a visibly-stabbed LaCroix recites the second-to-last stanza from the Jabberwocky poem, the Jabberwock referring to himself and the "beamish boy" referring to his son Nick, who attempted patricide in a previous episode. Bennett won a Gemini Award for Best Supporting Actor for the episode.

- An episode of The Muppet Show adapted most of Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, including this poem, for which special muppets of slithy toves, borogoves, mome raths, and the Jabberwock were designed, all based on Tenniel's illustrations.

- In the long running animated series The Simpsons, Marge's twin sisters Patty and Selma own an iguana named Jubjub.

- The Jabbawockeez is the name of a dance group in America's Best Dance Crew.

- The UK advert for the alcoholic drink Metz (drink) features the Judderman and is set to a poem based on Jabberwocky. Beware the Judderman my dear, when the moon is fat...

- In 1999, a movie titled "After Alice" is about a murderer obsessed with the book "Through the Looking-Glass" and the murderer is dubbed the Jabberwocky.

Music

- René Clausen composed a choral piece titled Jabberwocky out of this poem.

- Frumious Bandersnatch was the name chosen for a short-lived psychedelic rock band in the late 1960's, whose members later went on to join The Steve Miller Band and Journey.

- A recitation of "Jabberwocky" is included on A Book of Human Language, hip hop MC Aceyalone's sophomore album.

- Donovan set the poem to music on his album HMS Donovan.

- A full recitation of "Jabberwocky" is included on Ambrosia's 1975 self-titled album, in the song "Mama Frog".

- English band Hatcham Social have recorded their own rendition of the poem.

- The band Dzeltenie Pastnieki based the opening track on their 1984 album Alise around a Latvian translation of the poem, titled "Džabervokijs".

- The band The Crüxshadows quoted the poem on their Tears album in 2001.

- The band Forgive Durden released 'Beware The Jubjub Bird And Shun The Frumious Bandersnatch', their first single, in 2006.

- Fear Before has a song with the title of "Jabberwocky" on their self titled album in 2008.

- The band The Books feature excerpts from "Jabberwocky" frequently in their song "Vogt Dig For Kloppervok".

Games and toys

- Due to its popularity as a poem, a multitude of role-play and video games have used the artifacts and characters of the poem in their respective universes. In particular, the "vorpal swords" or "vorpal blades" are used in Dungeons & Dragons and numerous computer games and video games. Games based around this poem are also popular in the classroom. One activity that can be used to teach is to take all the nonsense words out and ask students to guess what they mean.

- The Monster in My Pocket toy line includes the Jabberwock (#50), which is made in the likeness of John Tenniel's illustration.

- In the computer game Sacrifice, one of the creatures of the earth god James is called the "Jabberocky", a massive elephantine creature.

- In the computer The Bard's Tale, one of the toughest monster was named the Jabberwock.

- In American Mcgee's Alice the Jabberwock is one of the main villans.

- In the computer game Myth II by Bungie, there are two net maps entitled Gimble in the Wabe and Gyre in the Wabe

See also

- Jabberwacky, a chatty Artificial Intelligence with a touch of wockiness

- Works influenced by Alice in Wonderland

Notes

- ↑ Gardner, Martin (1999). The Annotated Alice: The Definitive Edition. New York, NY: W.W. Norton and Company. "Few would dispute that Jabberwocky is the greatest of all nonsense poems in English.".

- ↑ Rundus, Raymond J. (October 1967). ""O Frabjous Day!": Introducing Poetry". The English Journal 56 (7): 958–963. doi:.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 From The Hunting of the Snark

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 Defined by Humpty Dumpty in Through the Looking-Glass.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 From the preface to The Hunting of the Snark, available at http://larrymikegarmon.com/engiv/jabberwock_puff.rtf

- ↑ According to Mischmasch, it is derived from the verb to bryl or broil.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 According to Carroll in a letter.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Definition from Oxford English Dictionary, credited to Lewis Carroll.

- ↑ Gyre is an actual word, circa 1566, meaning a circular or spiral motion or form; especially a giant circular oceanic surface current.

- ↑ From the preface to Through the Looking-Glass. Available at http://larrymikegarmon.com/engiv/jabberwock_puff.rtf

- ↑ Humpty Dumpty says "outgribing" when explaining the meaning. Outgrabe is, actually, the past tense; the present tense is outgribe.

- ↑ The North East England History Pages. Accessed 2007-07-22.

- ↑ http://miscoranda.com/150

- ↑ Lim, Keith. Jabberwocky Variations: Translations. Accessed 2007-10-21.

- ↑ Hofstadter, Douglas R. (1980). "Translations of Jabberwocky". Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid. ISBN 0-394-74502-7.

- ↑ http://www.jstor.org/stable/2718830?seq=20

- ↑ Gifford, Rob. "The Great Wall of the Mind." China Road. 237.

- ↑ Jabberwocky, and other parodies, in Roger Lancelyn Green: The Lewis Carroll Handbook, Dawson of Pall Mall, London 1970

- ↑ G. K. Chesterton: Lewis Carroll, in A Handful of Authors, ed. by Dorothy Collins, Sheed and Ward, London 1953

External links

- More about the origins and original meanings of the poem

- Lewis Carroll poetry at the Open Directory Project

- Character description of the Jabberwock

- Jabberwocky Reading (video)

|

||||||||||||||||||||