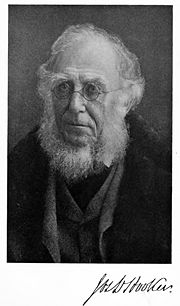

Joseph Dalton Hooker

| Joseph Dalton Hooker | |

Joseph Dalton Hooker

|

|

| Born | 30 June 1817 Halesworth, Suffolk |

|---|---|

| Died | 10 December 1911 (aged 94) Sunningdale, Berkshire |

| Nationality | English |

| Fields | botany |

| Notable awards | Linnean Society of London's Darwin-Wallace Medal in 1908. |

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, OM, GCSI, MD, FRS (30 June 1817 – 10 December 1911) was an English botanist and explorer.

Contents |

Early life and voyage on HMS Erebus

Hooker was born in Halesworth, Suffolk. He was the second son of the famous botanist Sir William Jackson Hooker and Maria Sarah Turner, eldest daughter of the banker Dawson Turner and sister-in-law of Francis Palgrave. From age seven, Hooker attended his father's lectures at Glasgow University where he was Regius Professor of Botany. Joseph formed an early interest in plant distribution and the voyages of explorers like Captain James Cook.[1] He was educated at the Glasgow High School and went on to study medicine at Glasgow University, graduating M.D. in 1839. This degree qualified him for employment in the Naval Medical Service: he joined renowned polar explorer Captain James Clark Ross's Antarctic expedition to the South Magnetic Pole after receiving a commission as Assistant-Surgeon on HMS Erebus.

The expedition consisted of two ships, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror; it was the last major voyage of exploration made entirely under sail.[2] Hooker was the youngest of the 128 man crew. He sailed on the Erebus and was assistant to Robert McCormick, who in addition to being the ship's Surgeon was instructed to collect zoological and geological specimens.[3] The ships sailed on 30 September 1839. Before journeying to Antarctica they visited Madeira, Tenerife, Santiago and Quail Island in the Cape Verde archipelago, St Paul Rocks, Trinidade east of Brazil, St Helena, and the Cape of Good Hope. Hooker made plant collections at each location and while travelling drew these and specimens of algae and sea life pulled aboard using tow nets.

From the Cape they entered the southern ocean. Their first stop was the Crozet Islands where they set down on Possession Island to deliver coffee to sealers. They departed for the Kerguelen Islands where they would spend several days. Hooker identified 18 flowering plants, 35 mosses and liverworts, 25 lichens and 51 algae, including some that were not described by surgeon William Anderson when James Cook had visited the islands in 1772.[4] The expedition spent some time in Hobart, Van Diemen's Land, and then moved on to the Auckland Islands and Campbell Island, and onward to Antarctica to locate the South Magnetic Pole. After spending 5 months in the Antarctic they returned to resupply in Hobart, then went on to Sydney, and the Bay of Islands in New Zealand. They left New Zealand to return to Antarctica. After spending 138 days at sea, and a collision between the Erebus and Terror, they sailed to the Falkland Islands, to Tierra del Fuego, back to the Falklands and onward to their third sortie into the Antarctic. They made a landing at Cockburn Island and after leaving the Antarctic, stopped at the Cape, St Helena and Ascension Island. The ships arrived back in England on 4 September 1843; the voyage had been a success for Ross as it was the first to confirm the existence of the southern continent and chart much of its coastline.[5]

Geological Survey of Great Britain

Failing to gain an academic position at the University of Edinburgh, Hooker declined a chair at Glasgow University. Instead, he took a position as botanist to the Geological Survey of Great Britain in 1846. He began work on palaeobotany, searching for fossil plants in the coal-beds of Wales. He became engaged to Frances Henslow, daughter of Charles Darwin's botany tutor John Stevens Henslow, but he was keen to continue to travel and gain more experience in the field. He wanted to travel to India and the Himalayas. In 1847 his father nominated him to travel to India and collect plants for Kew.

When Hooker returned to England, his father had been appointed director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, and so was now a prominent man of science. William Hooker, through his connections, secured an Admiralty grant of £1000 to defray the cost of plates for his son's Botany of the Antarctic Voyages, and an annual stipend of £200 for Joseph while he worked on the flora. Hooker's flora was also to include that collected on the voyages of Cook and Menzies held by the British Museum and collections made on the Beagle. The floras were illustrated by Walter Hood Fitch (trained in botanical illustration by William Hooker), who would go on to become the most prolific Victorian botanical artist.

Hooker's collections from the voyage were described eventually in one of two volumes published as the Flora Antarctica (1844–47). In the Flora he wrote about islands and their role in plant geography: the work made Hooker's reputation as a systemist and plant geographer.[6] His works on the voyage were completed with Flora Novae-Zelandiae (1851–53) and Flora Tasmaniae (1853–59).

Himalayan expedition

On 11 November 1847 Hooker left England for his three year long Himalayan expedition; he would be the first European to collect plants in the Himalaya. He received free passage on HMS Sidon, to the Nile and then travelled overland to Suez where he boarded a ship to India. He arrived in Calcutta on 12 January 1848, then travelled by elephant to Mirzapur, up the Ganges by boat to Siliguri and overland by pony to Darjeeling, arriving on 16 April 1848.

Hooker's expedition was based in Darjeeling where he stayed with naturalist Brian Houghton Hodgson. Through Hodgson he met British East India Company representative Archibald Campbell who negotiated Hooker's admission to Sikkim, which was finally approved in 1849. He was briefly taken prisoner by the Raja of Sikkim. Meanwhile, Hooker wrote to Darwin relaying to him the habits of animals in India, and collected plants in Bengal. He explored with local resident Charles Barnes, the travelled along the Great Runjeet river to its junction with the Tista River and Tonglu mountain in the Singalila range on the border with Nepal.

Hooker and a sizable party of local assistants departed for eastern Nepal on 27 October 1848. They travelled to Zongri, west over the spurs of Kangchenjunga, and north west along Nepal's passes into Tibet. In April 1849 he planned a longer expedition into Sikkim. Leaving on 3 May, he travelled north west up the Lachen Valley to the Kongra Lama Pass and then to the Lachoong Pass. Campbell and Hooker were imprisoned by the Dewan of Sikkim when they were travelling towards the Chola Pass in Tibet.[7][8] A British team was sent to negotiate with the king of Sikkim. However, they were released without any bloodshed [9] and Hooker returned to Darjeeling where he spent January and February of 1850 writing his journals, replacing specimens lost during his detention and planning a journey for his last year in India.

Reluctant to return to Sikkim, and unenthusiastic about travelling in Bhutan, he chose to make his last Himalayan expedition to Sylhet and the Khasi Hills in Assam. He was accompanied by Thomas Thompson, a fellow student from Glasgow University. They left Darjeeling on 1 May 1850, then sailed to the Bay of Bengal and travelled overland by elephant to the Khasi Hills and established a headquarters for their studies in Churra where they stayed until 9 December, when they began their trip back to England.

Hooker's survey of hitherto unexplored regions, the Himalayan Journals, dedicated to Charles Darwin, was published by the Calcutta Trigonometrical Survey Office and (The Minerva Library of Famous Books) Ward, Lock, Bowden & Co., 1891.

Friendship with Charles Darwin

- See also: Reaction to Darwin's theory and 1860 Oxford evolution debate

While on the Erebus, Hooker had read proofs of Charles Darwin's Voyage of the Beagle provided by Charles Lyell and had been very impressed by Darwin's skill as a naturalist. Following his return to England he was approached by Darwin who asked Hooker if he would classify the plants that he had collected in the Galápagos. Hooker agreed and the pair began a life-long friendship. In a letter dated 1844 Darwin shared with Hooker his early ideas on the transmutation of species and natural selection. He was probably the first person to hear of the theory. Their correspondence continued throughout the development of Darwin's theory and later Darwin wrote that Hooker was "the one living soul from whom I have constantly received sympathy".

Richard Freeman, in Charles Darwin--a Companion, wrote: "Hooker was Charles Darwin's greatest friend and confidant". Certainly they had extensive correspondence, but they also met face-to-face (Hooker visiting Darwin). Hooker and Lyell were the two people Darwin consulted (by letter) when Wallace's famous letter arrived at Down House, enclosing his paper on natural selection. Hooker was instrumental in creating the device whereby the Wallace paper was accompanied by Darwin's notes and his letter to Asa Gray (showing his prior realization of natural selection) in a presentation to the Linnean Society. Hooker was the one who formally presented this material to the Linnean Society meeting in 1858. In 1859 the author of The Origin of Species recorded his indebtedness to Hooker's wide knowledge and balanced judgment.

In 1859, Hooker published the Introductory Essay to the Flora Tasmaniae, the final part of the Botany of the Antarctic Voyage. It was in this essay (which appeared just one month after the publication of Charles Darwin's "On the Origin of Species"), that Hooker announced his support for the theory of evolution by natural selection, thus becoming the first recognised man of science to publicly back Darwin.

At the historic debate on evolution held at the Oxford University Museum on 30 June 1860, Bishop Samuel Wilberforce, Benjamin Brodie and Robert FitzRoy spoke against Darwin's theory, and Hooker and Thomas Henry Huxley defended it.[10] According to many contemporary accounts, including Hooker's own, it was he and not Huxley who delivered the most effective reply to Wilberforce's arguments.[10][11]

Hooker acted as president of the British Association at its Norwich meeting of 1868, when his address was remarkable for its championship of Darwinian theories. He was a close friend of Thomas Henry Huxley, a member of the X-Club, and the first of the three X-Clubbers (who dominated the Royal Society in the 1870s and early 1880s) to become President of the Royal Society.

Career

He started the series Flora Indica in 1855, together with Thomas Thompson. Their botanical observations and the publication of the Rhododendrons of Sikkim-Himalaya (1849–51), formed the basis of elaborate works on the rhododendrons of the Sikkim Himalaya and on the flora of India. His works were illustrated with lithographs by Walter Hood Fitch.

Among other journeys undertaken by Hooker were those to Palestine (1860), Morocco (1871), and the United States (1877), all yielding valuable scientific information.

In the midst of all this travelling in foreign countries he quickly built up for himself a high scientific reputation at home. In 1855 he was appointed assistant-director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, and in 1865 he succeeded his father as full director, holding the post for twenty years. Under the directorship of father and son Hooker, the Royal Botanical gardens of Kew rose to world renown.

At the early age of thirty he was elected a fellow of the Royal Society, and in 1873 he was chosen its president (till 1877). He received three of its medals: the Royal Medal in 1854, the Copley in 1887 and the Darwin Medal in 1892.

His greatest botanical work was the Flora of British India, published in seven volumes between 1872 and 1897. He was the author of numerous scientific papers and monographs, and his larger books included, in addition to those already mentioned, a standard Students Flora of the British Isles and a monumental work, the Genera plantarum[12] (1860–83), based on the collections at Kew, in which he had the assistance of George Bentham. In 1904, at the age of 87, he published A sketch of the Vegetation of the Indian Empire.

He continued the compilation of his father Sir William Jackson Hooker's project, Icones Plantarum (Illustrations of Plants), producing volumes eleven through nineteen.

On the publication of the last part of his Flora of British India in 1897 he was promoted Knight Grand Commander of the Star of India, the highest rank of the Order (he had been made a Knight Commander twenty years before). Ten years later, on attaining the age of ninety in 1907, he was awarded the Order of Merit.

Joseph Hooker died in his sleep at midnight at home on 10 December 1911 after a short and apparently minor illness. The Dean and Chapter of Westminster Abbey offered a grave near Darwin's in the nave but also insisted that Hooker be cremated before. His widow, Hyacinth, declined the proposal and eventually Hooker's body was buried, as he wished to be, alongside his father in the churchyard of St Anne’s on Kew Green, within short distance of Kew Gardens.

Hooker Oak in Chico, California is named after him.

Awards

He was awarded the Linnean Society of London's prestigious Darwin-Wallace Medal in 1908.

Marriages and children

In 1851 he married Frances Harriet Henslow (1825–1874), daughter of John Stevens Henslow. They had four sons and three daughters:

- William Henslow Hooker (1853–1942)

- Harriet Anne Hooker (1854–1945) married William Turner Thiselton-Dyer

- Charles Paget Hooker (1855–1933)

- Marie Elizabeth Hooker (1857–1863) died aged 6.

- Brian Harvey Hodgson Hooker (1860–1932)

- Reginald Hawthorn Hooker (1867–1944) statistician

- Grace Ellen Hooker (1868–1873) died aged 5.

After his first wife's death in 1874, in 1876 he married Hyacinth Jardine (1842–1921), daughter of William Samuel Symonds and the widow of Sir William Jardine. They had two sons:

- Joseph Symonds Hooker (1877–1940)

- Richard Symonds Hooker (1885–1950)

References

- ↑ Endersby, J. 2004. Hooker, Sir Joseph Dalton (1817–1911). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press

- ↑ Ward, P. 2001. Antarctic expedition, 1839-1843, James Clark Ross

- ↑ Desmond, R. 1999. Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker: Traveller and Plant Collector. Antique Collectors' Club and The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew ISBN 1-85149-305-0 p 18

- ↑ Desmond. 1999. p 36-42

- ↑ Desmond. 1999. p 85

- ↑ Desmond. 1999. p 91

- ↑ Letter number 1558: To J. D. Hooker. 10 March 1854. The Darwin Correspondence Online Database.

- ↑ Sanyal, R. B. (1896) Hours with Nature. S. K. Lahiri and Co. Page 34

- ↑ History of Darjeeling Darjeelingnews.net

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Lucas, JR (June 1979), "Wilberforce and Huxley: A Legendary Encounter", The Historical Journal 22 (2): 313–330, http://users.ox.ac.uk/~jrlucas/legend.html.

- ↑ Thomson, Keith Stewart (2000). "Huxley, Wilberforce and the Oxford Museum", American Scientist, May-June 2000. Retrieved on 14 February 2008.

- ↑ G. Bentham and J.D. Hooker, Genera plantarum London, A. Black (1862-1883), Botanicus, Missouri Botanical Garden Library

- ↑ Brummitt, R. K.; C. E. Powell (1992). Authors of Plant Names. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. ISBN 1-84246-085-4.

- Allen, Mea 1967. The Hookers of Kew 1785-1911.

- Huxley, Leonard 1918. Life and Letters of Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker OM GCSI. London, Murray.

- Scott, Michon (2008). "Rocky Road: Joseph Hooker". Retrieved on 2008-11-30.

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

- Joseph Hooker & Charles Darwin

- Joseph Dalton Hooker Joseph Dalton Hooker's work on orchids

- "Hooker, Joseph Dalton (1817 - 1911)" Botanicus, Missouri Botanical Garden Library

- A website dedicated to J D Hooker

- Works by Joseph Dalton Hooker at Project Gutenberg

- Gutenberg e-text of Hooker's Himalayan Journals

- Several scanned books at http://gallica.bnf.fr

| Awards and achievements | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Charles Robert Darwin |

Royal Medal 1854 |

Succeeded by John Obadiah Westwood |

| Preceded by Franz Ernst Neumann |

Copley Medal 1887 |

Succeeded by Thomas Henry Huxley |

| Preceded by Alfred Russel Wallace |

Darwin Medal 1892 |

Succeeded by Thomas Henry Huxley |

| Preceded by Alfred Richard Cecil Selwyn |

Clarke Medal 1885 |

Succeeded by Laurent-Guillaume de Koninck |

|

||||||||