Ivy League

| Ivy League (Ivies, Ancient Eight) | |

| Established: 1954 | |

| NCAA | Division I FCS |

|---|---|

| Members | 8 |

| Sports fielded | 33 (men's: 17; women's: 16) |

| Region | Northeast |

| Headquarters | Princeton, NJ |

| Commissioner | Jeffrey H. Orleans (since 1984) |

| Website | http://www.ivyleaguesports.com |

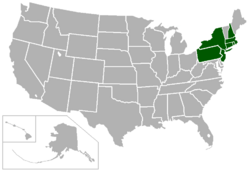

| Locations | |

|

|

The Ivy League is an athletic conference comprising eight private institutions of higher education in the Northeastern United States. The term is most commonly used to refer to those eight schools considered as a group.[1] The term also has connotations of academic excellence, selectivity in admissions, and a reputation for social elitism.

The term became official, especially in sports terminology, after the formation of the NCAA Division I athletic conference in 1954,[2] when much of the nation polarized around favorite college teams. The use of the phrase is no longer limited to athletics, and now represents an educational philosophy inherent to the nation's oldest schools.[3]

All of the Ivy League's institutions place near the top in the U.S. News & World Report college and university rankings and rank within the top one percent of the world's academic institutions in terms of financial endowment. Seven of the eight schools were founded during America's colonial period; the exception is Cornell, which was founded in 1865. Ivy League institutions, therefore, account for seven of the nine Colonial Colleges chartered before the American Revolution. The Ivies are all in the Northeast geographic region of the United States. They are privately owned and controlled, although many of them receive funding in the form of research grants from federal and state governments. Only Cornell has state-supported academic units, termed "statutory" or "contract" colleges, that are a part of the institution.

Undergraduate enrollments among the Ivy League schools range from about 4,000 to 14,000,[4] making them larger than those of a typical private liberal arts college and smaller than a typical public state university. Ivy League university financial endowments range from Brown's $2.8 billion to Harvard's $34.9 billion, the largest financial endowment of any academic institution in the world.

Contents |

Members

| Institution | Location | Athletic Nickname | Undergraduate enrollment | Motto |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown University | Providence, Rhode Island | Bears | 5,821[5] | In Deo speramus (In God we hope) |

| Columbia University | New York City, New York | Lions | 7,407[6] | In lumine Tuo videbimus lumen (In Thy light shall we see the light) |

| Cornell University | Ithaca, New York | Big Red | 13,510[7] | I would found an institution where any person can find instruction in any study. |

| Dartmouth College | Hanover, New Hampshire | Big Green | 4,164[8] | Vox clamantis in deserto (A voice crying in the wilderness, The voice of one crying in the wilderness)[9] |

| Harvard University | Cambridge, Massachusetts | Crimson | 6,715[10] | Veritas (Truth) |

| Princeton University | Princeton, New Jersey | Tigers | 4,790[11] | Dei sub numine viget (Under God's power she flourishes) |

| University of Pennsylvania | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | Quakers | 10,163[12] | Leges sine moribus vanae (Laws without morals are useless)[13] |

| Yale University | New Haven, Connecticut | Bulldogs | 5,275[14] | אורים ותומים Lux et veritas (Light and truth) |

History

Year founded

| Institution | Founded | Founding religious affiliation |

|---|---|---|

| Harvard University[15] | 1636, but named Harvard College in 1639 | Calvinist (specifically Congregationalist puritans; sided with Unitarians in the 1825 split from Congregationalism) |

| Yale University | 1701 as Collegiate School | Calvinist (Congregationalist) |

| University of Pennsylvania | 1740[16] | Nonsectarian,[17] but founded by Church of England members[18][19] |

| Princeton University | 1746 as College of New Jersey | Nonsectarian, but founded by Calvinists (Presbyterians) [20] |

| Columbia University | 1754 as King's College | Church of England |

| Brown University | 1764 as College of Rhode Island | Baptist, but founding charter promises "no religious tests" and "full liberty of conscience"[21] |

| Dartmouth College | 1769 | Calvinist (Congregationalist) |

| Cornell University | 1865 | Nonsectarian |

- Note Founding dates and religious affiliations are those stated by the institution itself. Many of them had complex histories in their early years and the stories of their origins are subject to interpretation. See footnotes for details where appropriate. "Religious affiliation" refers to financial sponsorship, formal association with, and promotion by, a religious denomination. All of the schools in the Ivy League are private and not currently associated with any religion.

Origin of the name

The first usage of "Ivy" in reference to a group of colleges is from sportswriter Stanley Woodward (1895–1965).

| “ | A proportion of our eastern ivy colleges are meeting little fellows another Saturday before plunging into the strife and the turmoil. | ” |

|

—Stanley Woodward, New York Tribune, October 14, 1933, describing the football season[22] |

||

According to book Dictionary of Word and Phrase Origins (1988), author William Morris writes that Stanley Woodward actually took the term from fellow New York Tribune sportswriter Caswell Adams. Morris writes that during the 1930s, the Fordham University football team was running roughshod over all its opponents. One day in the sports room at the Tribune, the merits of Fordham's football team were being compared to Princeton and Columbia. Adams remarked disparagingly of the latter two, saying they were "only Ivy League." Woodward, the sports editor of the Tribune, picked up the term and printed the next day.

Note though that in the above quote Woodward used the term ivy college, not ivy league as Adams is said to have used, so there is a discrepancy in this theory, although it seems certain the term ivy college and shortly later Ivy League acquired its name from the sports world.

The first known instance of the term Ivy League being used appeared in the Christian Science Monitor on February 7, 1935[23][24][25] Several sports-writers and other journalists used the term shortly later to refer to the older colleges, those along the northeastern seaboard of the United States, chiefly the nine institutions with origins dating from the colonial era, together with the United States Military Academy (West Point), the United States Naval Academy, and a few others. These schools were known for their long-standing traditions in intercollegiate athletics, often being the first schools to participate in such activities. However, at this time, none of these institutions would make efforts to form an athletic league.

The Ivy League's name derives from the ivy plants, symbolic of their age, that cover many of these institutions' historic buildings. The Ivy League universities are also called the "Ancient Eight" or simply the Ivies.

A common folk etymology attributes the name to the Roman numerals for four (IV), asserting that there was such a sports league originally with four members. The Morris Dictionary of Word and Phrase Origins helped to perpetuate this belief. The supposed "IV League" was formed over a century ago and consisted of Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and a 4th school that varies depending on who is telling the story.[26][27][28]

However, representatives from four schools, Rutgers, Princeton, Yale and Columbia met at the Fifth Avenue Hotel in Manhattan on October 19, 1873 to establish a set of rules governing their intercollegiate athletic competition, and particularly to codify the new game of college football (which at the time, largely resembled what is currently called rugby[29]). Though invited, Harvard chose not to attend. While no formal organization or conference was established, the results of this meeting governed athletic events between these schools well into the twentieth century.[30][31]

Before there was an Ivy League

Seven of the Ivy League schools are older than the American Revolution; Cornell was founded just after the American Civil War. These seven provided the overwhelming majority of the higher education in the Northern and Middle Colonies; their early faculties and founding boards were largely, therefore, drawn from other Ivy League institutions; there were also some British graduates - more from the University of Cambridge than Oxford, but also from the University of Edinburgh and elsewhere. Similarly, the founder of the College of William and Mary, in 1693, was a British graduate of the University of Edinburgh. And the founders of Rutgers, in 1766, were largely Ivy; and so for many of the colleges formed after the Revolution. Cornell provided Stanford University with its first president and most of Stanford's initial faculty members were Cornell professors. The founders of UC Berkeley came from Yale, hence their school colors of Yale Blue, and California Gold.[32]

As a group, the Ivy League has or had an identifiable Protestant "tone." Church of England King's College broke up in the Revolution, and was reformed as public non-sectarian Columbia College. In the early nineteenth century, the specific purpose of training Calvinist ministers was handed off to theological seminaries; but a denominational tone, and such relics as compulsory chapel, often lasted well into the twentieth century. Penn and Brown were officially founded as nonsectarian; Brown's charter promised no religious tests and "full liberty of conscience," but placed control in the hands of a board of twenty-two Baptists, five Quakers, four Congregationalists, and five Episcopalians. Cornell has always been strongly non-sectarian from its founding.

"Ivy League" therefore also became, like WASP, a way of referring to this elite, and elitist, class, even though institutions such as Cornell University were also among the first in the United States to reject racial and gender discrimination in their admissions policies. This sense[33] dates back to at least 1935.[34] Novels[35] and memoirs[36] attest this sense, as a social elite; to some degree independent of the actual schools.

After the Second World War, the present Ivy League institutions slowly widened their selection of students. They had always had distinguished faculties; some of the first Americans with doctorates had taught for them; but they now decided that they could not both be world-class research institutions and be competitive in the highest ranks of American college sport; in addition, the schools experienced the scandals of any other big-time football programs, although more quietly.[37]

History of the athletic league

The Ivies have been competing in sports as long as intercollegiate sports have existed in the United States. Boat clubs from Harvard and Yale met in the first sporting event held between students of two U.S. colleges on Lake Winnipesaukee, New Hampshire, in 1852. As an informal football league, the Ivy League dates from 1900 when Yale took the conference championship with a 5-0 record. For many years Army (the United States Military Academy) and Navy (the United States Naval Academy) were considered members, but dropped out shortly before formal organization. For instance, Army traditionally had a rivalry with Yale, and Rutgers had rivalries with Princeton and Columbia, which continue today in sports other than football.

The first formal league involving Ivy League teams was formed in 1902, when Columbia, Cornell, Harvard, Yale and Princeton formed the Eastern Intercollegiate Basketball League. They were later joined by Penn, Dartmouth and Brown.

Before the formal establishment of the Ivy League, there was an "unwritten and unspoken agreement among certain Eastern colleges on athletic relations". In 1935, The Associated Press reported on an example of collaboration between the schools:

"the athletic authorities of the so-called "Ivy League" are considering drastic measures to curb the increasing tendency toward riotous attacks on goal posts and other encroachments by spectators on playing fields.[38]"

Despite such collaboration, the universities did not seem to consider the formation of the league as imminent. Romeyn Berry, Cornell's manager of athletics, reported the situation in January 1936 as follows:

"I can say with certainty that in the last five years — and markedly in the last three months — there has been a strong drift among the eight or ten universities of the East which see a good deal of one another in sport toward a closer bond of confidence and cooperation and toward the formation of a common front against the threat of a breakdown in the ideals of amateur sport in the interests of supposed expediency."

"Please do not regard that statement as implying the organization of an Eastern conference or even a poetic 'Ivy League.' That sort of thing does not seem to be in the cards at the moment."[39]

Within a year of this statement and having held one-month-long discussions about the proposal, on December 3, 1936, the idea of "the formation of an Ivy League" gained enough traction among the undergraduate bodies of the universities that the Columbia Daily Spectator, The Cornell Daily Sun, The Dartmouth, The Harvard Crimson, The Daily Pennsylvanian, The Daily Princetonian and the Yale Daily News would simultaneously run an editorial entitled "Now Is the Time", encouraging the seven universities to form the league in an effort to preserve the ideals of athletics.[40] Part of the editorial read as follows:

"The Ivy League exists already in the minds of a good many of those connected with football, and we fail to see why the seven schools concerned should be satisfied to let it exist as a purely nebulous entity where there are so many practical benefits which would be possible under definite organized association. The seven colleges involved fall naturally together by reason of their common interests and similar general standards and by dint of their established national reputation they are in a particularly advantageous position to assume leadership for the preservation of the ideals of intercollegiate athletics."[41]

The proposal did not succeed — on January 11, 1937, the athletic authorities at the schools rejected the "possibility of a heptagonal league in football such as these institutions maintain in basketball, baseball and track." However, they noted that the league "has such promising possibilities that it may not be dismissed and must be the subject of further consideration."[42]

In 1945 the presidents of the eight schools signed the first Ivy Group Agreement, which set academic, financial, and athletic standards for the football teams. The principles established reiterated those put forward in the Harvard-Yale-Princeton Presidents' Agreement of 1916. The Ivy Group Agreement established the core tenet that an applicant's ability to play on a team would not influence admissions decisions:

"The members of the Group reaffirm their prohibition of athletic scholarships. Athletes shall be admitted as students and awarded financial aid only on the basis of the same academic standards and economic need as are applied to all other students."'[43]

In 1954, the date generally accepted as the birth of the Ivy League, the presidents extended the Ivy Group Agreement to all intercollegiate sports. Competition began with the 1956 season.

As late as the 1960s many of the Ivy League universities' undergraduate programs remained open only to men, with Cornell the only one to have been coeducational from its founding (1865) and Columbia being the last (1983) to become coeducational. Before they became coeducational, many of the Ivy schools maintained extensive social ties with nearby Seven Sisters women's colleges, including weekend visits, dances and parties inviting Ivy and Seven Sisters students to mingle. This was the case not only at Barnard College and Radcliffe College, which are adjacent to Columbia and Harvard, but at more distant institutions as well. The movie Animal House includes a satiric version of the formerly common visits by Dartmouth men to Massachusetts to meet Smith and Mount Holyoke women, a drive of more than two hours. As noted by Irene Harwarth, Mindi Maline, and Elizabeth DeBra, "the 'Seven Sisters' was the name given to Barnard, Smith, Mount Holyoke, Vassar, Bryn Mawr, Wellesley, and Radcliffe, because of their parallel to the Ivy League men’s colleges."[44]

Cohesiveness of the group

The Ivy League schools are highly selective, with acceptance rates ranging from about 7 to 20 percent from an application pool that consists of the top high school students in the country.[45]

These universities engage in a heated competition to attract students, illustrated by a 2002 incident in which admissions officers at Princeton logged into the Yale admissions website fourteen times to view the admissions status of cross-applicants, using the names, birth dates, and social security numbers indicated on their Princeton applications; Princeton later asserted that it had been considering a similar system of early Internet notification, and was surprised to find that Yale had used no password besides the Social Security number. Yale's administration notified the FBI about the actions after conducting its own investigation. Princeton moved one admissions official to a different department over the incident and the university's Dean of Admissions retired soon thereafter, though Princeton president Shirley Tilghman said that the dean's decision to retire was unconnected to the incident.[46]

Collaboration between the member schools is illustrated by the student-led Ivy Council that meets in the fall and spring of each year, with representatives from every Ivy League school. At these multi-day conferences, student representatives from each school meet to discuss issues facing their respective institutions, with a variety of topics ranging from financial aid to gender-neutral housing.

Social elitism

The phrase Ivy League historically has been perceived as connected not only with academic excellence, but also with social elitism. In 1936, sportwriter John Kieran noted that student editors at Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Cornell, Columbia, Dartmouth, and Penn were advocating the formation of an athletic association. In urging them to consider "Army and Navy and Georgetown and Fordham and Syracuse and Brown and Pitt" as candidates for membership, he exhorted:

- "It would be well for the proponents of the Ivy League to make it clear (to themselves especially) that the proposed group would be inclusive but not 'exclusive' as this term is used with a slight up-tilting of the tip of the nose".[47]

The Ivy League was specifically associated with the WASP establishment.[48] Phrases such as "Ivy League snobbery"[49] are ubiquitous in nonfiction and fiction writing of the twentieth century. A Louis Auchincloss character dreads "the aridity of snobbery which he knew infected the Ivy League colleges".[35] A business writer, warning in 2001 against discriminatory hiring, presented a cautionary example of an attitude to avoid (the bracketed phrase is his):

- "We Ivy Leaguers [read: mostly white and Anglo] know that an Ivy League degree is a mark of the kind of person who is likely to succeed in this organization."[50]

Aspects of Ivy stereotyping were illustrated during the 1988 presidential election, when George H. W. Bush (Yale '48) derided Michael Dukakis (graduate of Harvard Law School) for having "foreign-policy views born in Harvard Yard's boutique."[51] New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd asked "Wasn't this a case of the pot calling the kettle elite?" Bush explained however that, unlike Harvard, Yale's reputation was "so diffuse, there isn't a symbol, I don't think, in the Yale situation, any symbolism in it.... Harvard boutique to me has the connotation of liberalism and elitism" and said Harvard in his remark was intended to represent "a philosophical enclave" and not a statement about class.[52]. Columnist Russell Baker opined that "Voters inclined to loathe and fear elite Ivy League schools rarely make fine distinctions between Yale and Harvard. All they know is that both are full of rich, fancy, stuck-up and possibly dangerous intellectuals who never sit down to supper in their undershirt no matter how hot the weather gets."[53]

Cooperation

Seven of the eight schools (Harvard excluded) participate in the Borrow Direct interlibrary loan program, making a total of 88 million items available to participants with a waiting period of four working days.[54] This ILL program is not affiliated with the formal Ivy arrangement.

The governing body of the Ivy League is the Council of Ivy Group Presidents. During their meetings, the presidents often discuss common procedures and initiatives.

Competition and athletics

Ivy champions are recognized in 33 men's and women's sports. In some sports, Ivy teams actually compete as members of another league, the Ivy championship being decided by isolating the members' records in play against each other. (For example, the six league members who participate in ice hockey do so as members of ECAC Hockey; but an Ivy champion is extrapolated each year.) Unlike all other Division I basketball conferences, the Ivy League has no tournament for the league title;[55] the school with the best conference record represents the conference in the Division I NCAA Basketball Tournament (with a playoff in the case of a tie).

On average, each Ivy school has more than 35 varsity teams. All eight are in the top 20 for number of sports offered for both men and women among Division I schools. Unlike most Division I athletic conferences, the Ivy League prohibits the granting of athletic scholarships; all scholarships awarded are need-based (financial aid).[56] Ivy League teams out of league games are usually against the members of the Patriot League which have similar academic standards and athletic scholarship policies.

In the time before recruiting for college sports became dominated by those offering athletic scholarships and lowered academic standards for athletes, the Ivy League was successful in many sports relative to other universities in the country. In particular, Princeton won 24 recognized national championships in college football (Last Div I championship in 1911), and Yale won 19 (Last Div I championship in 1927). Both of these totals are considerably higher than those of other historically strong programs such as Alabama and Notre Dame, which have won 12, and USC, which has won 11. Yale, whose coach Walter Camp was the "Father of American Football," held on to its place as the all-time wins leader in college football throughout the entire 20th century, but was finally passed by Michigan on November 10, 2001. Currently Dartmouth holds the record for most Ivy League football titles, with 17.

Although no longer as successful nationally as they once were in many of the more popular college sports, the Ivy League is still competitive in others. One such example is rowing. All of the Ivies have historically been among the top crews in the nation, and most continue to be so today. (Other historical top crews include Cal, Washington, Wisconsin and Navy). Most recently, on the men's side, Harvard won the Intercollegiate Rowing Association Championships in 2003, 2004, 2005, and on the women's side, Harvard and Brown won the 2003 and 2004 NCAA Rowing Championships, respectively. Additionally, Cornell's men's lightweight team won back to back to back IRA National Championships in 2006, 2007 and 2008. The Ivy League schools are also very competitive in both men's and women's hockey.

The Ivy League is home to some of the oldest college rugby teams. These teams meet annually to compete in a tourney. The 2006 Ivy League Tournament was hosted by Yale, and the 2005 tournament was hosted by the University of Pennsylvania. Though the women's rugby teams at the Ivy League schools are much younger, they too compete in an annual Ivy League Tournament, often hosted by Brown.

Internal rivalries

Harvard and Yale are celebrated football and crew rivals.

Princeton and Penn are longstanding men's basketball rivals[57] and "Puck Fenn", "Puck Frinceton", and "Pennetrate the Puss" t-shirts are worn at games.[58] In only five instances in the history of Ivy League basketball, and in only two seasons since Dartmouth's 1957–58 title, has neither Penn nor Princeton won at least a share of the Ivy League title in basketball,[59] with each champion or co-champion 25 times. Penn has won 21 outright, Princeton 18 outright. Princeton has been a co-champion 7 times, sharing 4 of those titles with Penn (these 4 seasons represent the only times Penn has been co-champion). Cornell is the reigning (2008) champion.

Rivalries exist between other Ivy league teams in other sports, including Cornell and Harvard in hockey, and Harvard and Penn in football (Penn and Harvard have each had two unbeaten seasons since 2001.[60]).

In addition, no team other than Harvard or Princeton has won the men's swimming conference title since 1972, with Harvard winning the 34 year series 20–16 as of 2008.

Conference facilities

| School[61] | Football stadium | Basketball arena | Ice hockey rink | Soccer stadium | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Capacity | Name | Capacity | Name | Capacity | Name | Capacity | |

| Brown | Brown Stadium | 20,000 | Pizzitola Sports Center | 2,800 | Meehan Auditorium | 3,100 | Stevenson Field | 3,500 |

| Columbia | Wien Stadium | 17,000 | Levien Gymnasium | 3,408 | N/A | Columbia Soccer Stadium | 3,500 | |

| Cornell | Schoellkopf Field | 25,597 | Newman Arena | 4,473 | Lynah Rink | 4,267 | Charles F. Berman Field | 1,000 |

| Dartmouth | Memorial Field | 13,000 | Leede Arena | 2,100 | Thompson Arena | 5,000 | Burnham Soccer Facility | 1,600 |

| Harvard | Harvard Stadium | 30,898 | Lavietes Pavilion | 2,195 | Bright Hockey Center | 2,850 | Ohiri Field | 1,500 |

| Penn | Franklin Field | 52,593 | The Palestra | 8,722 | The Class of 1923 Arena | 2,900 | Rhodes Field | ~700 |

| Princeton | Princeton Stadium | 27,800 | Jadwin Gymnasium | 6,854 | Hobey Baker Memorial Rink | 2,094 | Roberts Stadium | 3,000 |

| Yale | Yale Bowl | 64,269 | Payne Whitney Gym | 3,100 | Ingalls Rink | 3,486 | Reese Stadium | 3,000 |

Dartmouth also owns and operates the Dartmouth Skiway, the home racing grounds for the 2007 NCAA skiing champions.

Other Ivies

Marketing groups, journalists, and some educators sometimes promote other colleges as "Ivies," as in Little Ivies; Public Ivies; Southern Ivies; and Canadian Ivies. These uses of "ivy" are intended to promote the other schools by comparing them to the Ivy League, but unlike the "Ivy League" label, they have no canonical definition. For example, in the 2007 edition of Newsweek's How to Get Into College Now, the editors designated twenty-five schools as "New Ivies," some of which share no characteristics with the Ivy League colleges except a good reputation.[62]

The term "Ivy Plus" is sometimes used to refer to the eight plus several other schools for purposes of alumni associations[63], university affiliations[64][65][66], or endowment analysis[67][68]. The inclusion of non-Ivy Leagues schools under this term is not highly consistent across uses. Among these other schools, the most commonly recurring ones are Stanford University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Championships

Football

|

|

Men's Basketball

|

|

Men's Ice Hockey

|

|

See also

- Big Three (universities) — a term used to refer to Harvard, Yale, and Princeton

- Colonial colleges — the oldest U. S. colleges, overlaps the Ivy League with the exception of Cornell

- Hidden Ivies: Thirty Colleges of Excellence

- Jesuit Ivy — Complimentary use of "Ivy" to characterize Boston College

- Little Ivies — group of U.S. liberal arts colleges that parallel the Ivy League in some respects

- Public Ivies — Group of public U.S. universities thought to "provide an Ivy League collegiate experience at a public school price"

- Seven Sisters — Historically, these were women's colleges each of which had a close tie to an Ivy League school.

- Southern Ivies — Complimentary use of "Ivy" to characterize excellent universities in the U. S. South

- Canadian Ivy League

- Category:University organizations — other groups of universities

References

- ↑ "Princeton Campus Guide - Ivy League". Retrieved on 2007-04-26.

- ↑ "IvySport - History". Retrieved on 2008-01-06.

- ↑ "What is the origin of the term, Ivy League?". Retrieved on 2006-05-17.

- ↑ Dartmouth and Cornell respectively

- ↑ Facts about Brown University

- ↑ Planning and Institutional Research | FACTS

- ↑ Cornell Factbook - Undergraduate Enrollment

- ↑ Microsoft Word - header_factbook.doc

- ↑ The former English translation is that more commonly used by Dartmouth itself

- ↑ Harvard University Office of News and Public Affairs | Harvard at a Glance

- ↑ About Princeton University - A Princeton Profile

- ↑ Penn: Facts and Figures

- ↑ A Guide to the Usage of the Seal and Arms of the University of Pennsylvania University Archives and Records Center, University of Pennsylvania; accessed 4-29-08

- ↑ Factsheet - Statistical Summary of Yale University

- ↑ The institution, though founded in 1636, did not receive its name until 1639. It was nameless for its first two years

- ↑ See University of Pennsylvania for details the circumstances of Penn's origin. Penn's self-stated founding date of 1740 is a matter of longstanding controversy between Penn and Princeton boosters.

- ↑ Penn's website, like other sources, makes an important point of Penn's heritage being nonsectarian, associated with Benjamin Franklin and the Academy of Philadelphia's nonsectarian board of trustees: "The goal of Franklin's nonsectarian, practical plan would be the education of a business and governing class rather than of clergymen."[1]. Jencks and Riesman (2001) write "The Anglicans who founded the University of Pennsylvania, however, were evidently anxious not to alienate Philadelphia's Quakers, and they made their new college officially nonsectarian." Franklin himself was a self-described "thorough Deist." In Franklin's 1749 founding Proposals relating to the education of youth in Pensilvania(page images), religion is not mentioned directly as a subject of study, but he states in a footnote that the study of "History will also afford frequent Opportunities of showing the Necessity of a Publick Religion, from its Usefulness to the Publick; the Advantage of a Religious Character among private Persons; the Mischiefs of Superstition, &c. and the Excellency of the CHRISTIAN RELIGION above all others antient or modern." Starting in 1751, the same trustees also operated a Charity School for Boys, whose curriculum combined "general principles of Christianity" with practical instruction leading toward careers in business and the "mechanical arts." [2], and thus might be described as "non-denominational Christian." The charity school was originally planned, and chartered on paper, in 1740, by followers of evangelist George Whitefield, but was not built and did not operate until the charter was assumed by the Academy of Philadelphia in 1751. Since 1895, Penn has claimed a founding date of 1740, based on the charity school's charter date and the premise that it had institutional identity with the Academy of Philadelphia. Whitefield was a firebrand Methodist associated with The Great Awakening; since the Methodists did not formally break from the Church of England until 1784, Whitefield in 1740 would be labelled Episcopalian, and in fact Brown University, emphasizing its own pioneering nonsectarianism, refers to Penn's origin as "Episcopalian"[3]). Penn is sometimes assumed to have Quaker ties (its athletic teams are called "Quakers," and the cross-registration alliance between Penn, Haverford, Swarthmore and Bryn Mawr is known as the "Quaker Consortium.") But Penn's website does not assert any formal affiliation with Quakerism, historic or otherwise, and Haverford College implicitly asserts a non-Quaker origin for Penn when it states that "Founded in 1833, Haverford is the oldest institution of higher learning with Quaker roots in North America."[4]

- ↑ Protestant Episcopal Church - LoveToKnow 1911

- ↑ Brown Admission: Our History

- ↑ University Chapel: Orange Key Virtual Tour of Princeton University

- ↑ Brown's website characterizes it as "the Baptist answer to Congregationalist Yale and Harvard; Presbyterian Princeton; and Episcopalian Penn and Columbia," but adds that at the time it was "the only one that welcomed students of all religious persuasions."[5] Brown's charter stated that "into this liberal and catholic institution shall never be admitted any religious tests, but on the contrary, all the members hereof shall forever enjoy full, free, absolute, and uninterrupted liberty of conscience." The charter called for twenty-two of the thirty-six trustees to be Baptists, but required that the remainder be "five Friends, four Congregationalists, and five Episcopalians"[6]

- ↑ "Yale Book of Quotations" (2006) Yale University Press edited by Fred R. Shapiro

- ↑ "The Yale Book of Quotations" (2006) Yale University Press, edited by Fred R. Shapiro

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary entry for "Ivy League"

- ↑ Ivy League Sports

- ↑ The Chicago Public Library reports the "IV League" explanation,[7] sourced only from the Morris Dictionary of Word and Phrase Origins.

- ↑ Various Ask Ezra student columns report the "IV League" explanation, apparently relying on the Morris Dictionary of Word and Phrase Origins as the sole source: [8] [9] [10]

- ↑ The Penn Current / October 17, 2002 / Ask Benny

- ↑ Rutgers - The Birthplace of Intercollegiate Football

- ↑ Encyclopedia Britannica accessed 10 September 2006.

- ↑ A History of American Football until 1889 accessed 10 September 2006.

- ↑ Resource: Student history

- ↑ Epstein, Joseph (2003). Snobbery: The American Version. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-34073-4. p. 55, "by WASP Baltzell meant something much more specific; he intended to cover a select group of people who passed through a congeries of elite American institutions: certain eastern prep schools, the Ivy League colleges, and the Episcopal Church among them." and Wolff, Robert Paul (1992). The Ideal of the University. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 1-56000-603-X. p. viii: "My genial, aristocratic contempt for Clark Kerr's celebration of the University of California was as much an expression of Ivy League snobbery as it was of radical social critique."

- ↑ The Associated Press (1935-10-5). "Yale Jinx Overcome, Dartmouth Now Seeks To Break Spell Cast by Princeton Teams", The New York Times, p. 35.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Auchincloss, Louis (2004). East Side Story. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-45244-3. p. 179, "he dreaded the aridity of snobbery which he knew infected the Ivy League colleges"

- ↑ McDonald, Janet (2000). Project Girl. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22345-4. p. 163 "Newsweek is a morass of incest, nepotism, elitism, racism and utter classic white male patriarchal corruption.... It is completely Ivy League—a Vassar/Columbia J-School dumping ground... I will always be excluded, regardless of how many Ivy League degrees I acquire, because of the next level of hurdles: family connections and money."

- ↑ scandals: James Axtell, The Making of Princeton University (2006), p.274; quoting a former executive director of the Ivy League

- ↑ The Associated Press (1935-12-6). "Colleges Searching for Check On Trend to Goal Post Riots", The New York Times, p. 33.

- ↑ Robert F. Kelley (1936-1-17). "Cornell Club Here Welcomes Lynah", The New York Times, p. 22.

- ↑ "Immediate Formation of Ivy League Advocated at Seven Eastern Colleges", The New York Times (1936-12-3), p. 33.

- ↑ The Harvard Crimson :: News :: AN EDITORIAL

- ↑ "Plea for an Ivy Football League Rejected by College Authorities", The New York Times (1937-1-12), p. 26.

- ↑ http://www.thecrimson.com/article.aspx?ref=128992 The Harvard Crimson Ivy League: Formalizing the Fact Saturday, October 13, 1956

- ↑ Archived: Women's Colleges in the United States: History, Issues, and Challenges

- ↑ [11]

- ↑ Princeton removes LeMenager from admission office for violations - The Daily Princetonian

- ↑ Kieran, John (1936), "Sports of the Times", The New York Times, December 4, 1936, p. 36. "There will now be a little test of the "the power of the press" in intercollegiate circles since the student editors at Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Cornell, Columbia, Dartmouth and Penn are coming out in a group for the formation of an Ivy League in football. The idea isn't new.... It would be well for the proponents of the Ivy League to make it clear (to themselves especially) that the proposed group would be inclusive but not "exclusive" as this term is used with a slight up-tilting of the tip of the nose." He recommended the consideration of "plenty of institutions covered with home-grown ivy that are not included in the proposed group. [such as ] Army and Navy and Georgetown and Fordham and Syracuse and Brown and Pitt, just to offer a few examples that come to mind" and noted that "Pitt and Georgetown and Brown and Bowdoin and Rutgers were old when Cornell was shining new, and Fordham and Holy Cross had some building draped in ivy before the plaster was dry in the walls that now tower high about Cayuga's waters."

- ↑ Epstein, Joseph (2003). Snobbery: The American Version. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-34073-4. p. 55, "by WASP Baltzell meant something much more specific; he intended to cover a select group of people who passed through a congeries of elite American institutions: certain eastern prep schools, the Ivy League colleges, and the Episcopal Church among them."

- ↑ Wolff, Robert Paul (1992). The Ideal of the University. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 1-56000-603-X. p. viii: "My genial, aristocratic contempt for Clark Kerr's celebration of the University of California was as much an expression of Ivy League snobbery as it was of radical social critique."

- ↑ Williams, Mark (2001). The 10 Lenses: your guide to living and working in a multicultural world. Capital Books. ISBN The 10 Lenses: your guide to living and working in a multicultural world., p. 85

- ↑ Webster G. Tarpley and Anton Chaitkin. "George Bush: The Unauthorized Biography: Chapter XXII Bush Takes The Presidency". Webster G. Tarpley. Retrieved on 2006-12-17.

- ↑ Dowd, Maureen (1998), "Bush Traces How Yale Differs From Harvard." The New York Times, June 11, 1998, p. 10

- ↑ Baker, Russell (1998), "The Ivy Hayseed." The New York Times, June 15, 1988, p. A31

- ↑ Columbia's Borrow Direct website

- ↑ May The Madness Begin by Mark Starr Newsweek.com; March 14, 2002; accessed January 25, 2008

- ↑ Ivy League Sports

- ↑ The game: the tables are turned – Penn hoops travel to Jadwin tonight for premier rivalry of Ivy League basketball - The Daily Princetonian

- ↑ The rivalry? Not with Penn's paltry performance this season - The Daily Princetonian

- ↑ Ivy League Basketball

- ↑ Ivy League Football

- ↑ "Ivy Facilities". Retrieved on 2006-06-10.

- ↑ America's 25 New Elite 'Ivies' | Newsweek Best High Schools | Newsweek.com

- ↑ "Ivy Plus Society". Retrieved on 2008-11-24.

- ↑ "Ivy Plus Sustainability Working Group". Yale. Retrieved on 2008-11-24.

- ↑ "ivy plus annual fund". harvard. Retrieved on 2008-11-24.

- ↑ "Ivy + Alumni Relations Conference". Princeton. Retrieved on 2008-11-24.

- ↑ Weisman, Robert (November 2, 2007). "Risk pays off for endowments", The Boston Globe. Retrieved on 2008-11-24.

- ↑ PERLOFF-GILES, ALEXANDRA (March 11, 2008). "Columbia, MIT Fall Into Line on Aid", The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved on 2008-11-24.

- ↑ Ivy League Football Champions 03.14.2008

- ↑ Ivy League Basketball Champions 11.15.2007

- ↑ Ivy League Ice Hockey Champions 03.16.2008

External links

Conference

Members homepages

- Brown University

- Columbia University

- Cornell University

- Dartmouth College

- Harvard University

- Princeton University

- University of Pennsylvania

- Yale University

Athletic homepages

- Brown Bears

- Columbia Lions

- Cornell Big Red

- Dartmouth Big Green

- Harvard Crimson

- Penn Quakers

- Princeton Tigers

- Yale Bulldogs

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

||||||||