Mathematics in medieval Islam

In the history of mathematics, Islamic mathematics or Arabic mathematics refers to the mathematics developed in the Islamic world between 622 and 1600, in the part of the world where Islam was the dominant religious and cultural influence, and Arabic was the dominant language of scholarship. Islamic science and mathematics flourished under the Islamic caliphate (also known as the Islamic Empire) established across the Middle East, Central Asia, North Africa, Sicily, the Iberian Peninsula, and in parts of France and India in the 8th century. The center of Islamic mathematics was located in present-day Iraq and Iran, but at its greatest extent stretched from Turkey, North Africa and Spain in the west, to India in the east.[1]

While most scientists in this period were Muslims and Arabic was the dominant language—much like Latin in Medieval Europe, Arabic was used as the written language of scholars throughout the Islamic world at the time—contributions were made by people of different ethnic groups (Arabs, Persians, Berbers, Moors, Turks) and sometimes different religions (Muslims, Christians, Jews, Sabians, Zoroastrians, irreligious).[2]

Contents |

Use of the term "Islam"

Bernard Lewis writes the following on the historical usage of the term "Islam" in What Went Wrong? Western Impact and Middle Eastern Response:[3]

"There have been many civilizations in human history, almost all of which were local, in the sense that they were defined by a region and an ethnic group. This applied to all the ancient civilizations of the Middle East—Egypt, Babylon, Persia; to the great civilizations of Asia—India, China; and to the civilizations of Pre-Columbian America. There are two exceptions: Christendom and Islam. These are two civilizations defined by religion, in which religion is the primary defining force, not, as in India or China, a secondary aspect among others of an essentially regional and ethnically defined civilization. Here, again, another word of explanation is necessary."

"In English we use the word “Islam” with two distinct meanings, and the distinction is often blurred and lost and gives rise to considerable confusion. In the one sense, Islam is the counterpart of Christianity; that is to say, a religion in the strict sense of the word: a system of belief and worship. In the other sense, Islam is the counterpart of Christendom; that is to say, a civilization shaped and defined by a religion, but containing many elements apart from and even hostile to that religion, yet arising within that civilization."

In this article, "Islam" is used in the meaning of a civilization.

Origins and influences

The first century of the Islamic Arab Empire saw almost no scientific or mathematical achievements since the Arabs, with their newly conquered empire, had not yet gained any intellectual drive and research in other parts of the world had faded. In the second half of the eighth century Islam had a cultural awakening, and research in mathematics and the sciences increased.[4] The Muslim Abbasid caliph al-Mamun (809-833) is said to have had a dream where Aristotle appeared to him, and as a consequence al-Mamun ordered that Arabic translation be made of as many Greek works as possible, including Ptolemy's Almagest and Euclid's Elements. Greek works would be given to the Muslims by the Byzantine Empire in exchange for treaties, as the two empires held an uneasy peace.[4] Many of these Greek works were translated by Thabit ibn Qurra (826-901), who translated books written by Euclid, Archimedes, Apollonius, Ptolemy, and Eutocius.[5] Historians are in debt to many Islamic translators, for it is through their work that many ancient Greek texts have survived only through Arabic translations.

Greek, Indian and Babylonian all played an important role in the development of early Islamic mathematics. The works of mathematicians such as Euclid, Apollonius, Archimedes, Diophantus, Aryabhata and Brahmagupta were all acquired by the Islamic world and incorporated into their mathematics. Perhaps the most influential mathematical contribution from India was the decimal place-value Indo-Arabic numeral system, also known as the Hindu numerals.[6] The Persian historian al-Biruni (c. 1050) in his book Tariq al-Hind states that the Abbasid caliph al-Ma'mun had an embassy in India from which was brought a book to Baghdad that was translated into Arabic as Sindhind. It is generally assumed that Sindhind is none other than Brahmagupta's Brahmasphuta-siddhanta.[7] The earliest translations from Sanskrit inspired several astronomical and astrological Arabic works, now mostly lost, some of which were even composed in verse.[8]

Indian influences were later overwhelmed by Greek mathematical and astronomical texts. It is not clear why this occurred but it may have been due to the greater availability of Greek texts in the region, the larger number of practitioners of Greek mathematics in the region, or because Islamic mathematicians favored the deductive exposition of the Greeks over the elliptic Sanskrit verse of the Indians. Regardless of the reason, Indian mathematics soon became mostly eclipsed by or merged with the "Graeco-Islamic" science founded on Hellenistic treatises.[8] Another likely reason for the declining Indian influence in later periods was due to Sindh achieving independance from the Caliphate, thus limiting access to Indian works. Nevertheless, Indian methods continued to play an important role in algebra, arithmetic and trigonometry.[9]

Besides the Greek and Indian tradition, a third tradition which had a significant influence on mathematics in medieval Islam was the "mathematics of practitioners", which included the applied mathematics of "surveyors, builders, artisans, in geometric design, tax and treasury officials, and some merchants." This applied form of mathematics transcended ethnic divisions and was a common heritage of the lands incorporated into the Islamic world.[6] This tradition also includes the religious observances specific to Islam, which served as a major impetus for the development of mathematics as well as astronomy.[10]

Islam and mathematics

A major impetus for the flowering of mathematics as well as astronomy in medieval Islam came from religious observances, which presented an assortment of problems in astronomy and mathematics, specifically in trigonometry, spherical geometry,[10] algebra[11] and arithmetic.[12]

The Islamic law of inheritance served as an impetus behind the development of algebra (derived from the Arabic al-jabr) by Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī and other medieval Islamic mathematicians. Al-Khwārizmī's Hisab al-jabr w’al-muqabala devoted a chapter on the solution to the Islamic law of inheritance using algebra. He formulated the rules of inheritance as linear equations, hence his knowledge of quadratic equations were not required.[11] Later mathematicians who specialized in the Islamic law of inheritance included Al-Hassār, who developed the modern symbolic mathematical notation for fractions in the 12th century,[12] and Abū al-Hasan ibn Alī al-Qalasādī, who developed an algebraic notation which took "the first steps toward the introduction of algebraic symbolism" in the 15th century.[13]

In order to observe holy days on the Islamic calendar in which timings were determined by phases of the moon, astronomers initially used Ptolemy's method to calculate the place of the moon and stars. The method Ptolemy used to solve spherical triangles, however, was a clumsy one devised late in the first century by Menelaus of Alexandria. It involved setting up two intersecting right triangles; by applying Menelaus' theorem it was possible to solve one of the six sides, but only if the other five sides were known. To tell the time from the sun's altitude, for instance, repeated applications of Menelaus' theorem were required. For medieval Islamic astronomers, there was an obvious challenge to find a simpler trigonometric method.[10]

Regarding the issue of moon sighting, Islamic months do not begin at the astronomical new moon, defined as the time when the moon has the same celestial longitude as the sun and is therefore invisible; instead they begin when the thin crescent moon is first sighted in the western evening sky.[10] The Qur'an says: "They ask you about the waxing and waning phases of the crescent moons, say they are to mark fixed times for mankind and Hajj."[14][15] This led Muslims to find the phases of the moon in the sky, and their efforts led to new mathematical calculations.[16]

Predicting just when the crescent moon would become visible is a special challenge to Islamic mathematical astronomers. Although Ptolemy's theory of the complex lunar motion was tolerably accurate near the time of the new moon, it specified the moon's path only with respect to the ecliptic. To predict the first visibility of the moon, it was necessary to describe its motion with respect to the horizon, and this problem demands fairly sophisticated spherical geometry. Finding the direction of Mecca and the time of Salah are the reasons which led to Muslims developing spherical geometry. Solving any of these problems involves finding the unknown sides or angles of a triangle on the celestial sphere from the known sides and angles. A way of finding the time of day, for example, is to construct a triangle whose vertices are the zenith, the north celestial pole, and the sun's position. The observer must know the altitude of the sun and that of the pole; the former can be observed, and the latter is equal to the observer's latitude. The time is then given by the angle at the intersection of the meridian (the arc through the zenith and the pole) and the sun's hour circle (the arc through the sun and the pole).[10][17]

Muslims are also expected to pray towards the Kaaba in Mecca and orient their mosques in that direction. Thus they need to determine the direction of Mecca (Qibla) from a given location.[18][19] Another problem is the time of Salah. Muslims need to determine from celestial bodies the proper times for the prayers at sunrise, at midday, in the afternoon, at sunset, and in the evening.[10][17]

Importance

J. J. O'Conner and E. F. Robertson wrote in the MacTutor History of Mathematics archive:

"Recent research paints a new picture of the debt that we owe to Islamic mathematics. Certainly many of the ideas which were previously thought to have been brilliant new conceptions due to European mathematicians of the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries are now known to have been developed by Arabic/Islamic mathematicians around four centuries earlier. In many respects, the mathematics studied today is far closer in style to that of Islamic mathematics than to that of Greek mathematics."

R. Rashed wrote in The development of Arabic mathematics: between arithmetic and algebra:

"Al-Khwarizmi's successors undertook a systematic application of arithmetic to algebra, algebra to arithmetic, both to trigonometry, algebra to the Euclidean theory of numbers, algebra to geometry, and geometry to algebra. This was how the creation of polynomial algebra, combinatorial analysis, numerical analysis, the numerical solution of equations, the new elementary theory of numbers, and the geometric construction of equations arose."

Biographies

- Al-Ḥajjāj ibn Yūsuf ibn Maṭar (786 – 833)

- Al-Ḥajjāj translated Euclid's Elements into Arabic.

- Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī (c. 780 Khwarezm/Baghdad – c. 850 Baghdad)

- Al-Khwārizmī was a Persian mathematician, astronomer, astrologer and geographer. He worked most of his life as a scholar in the House of Wisdom in Baghdad. His Algebra was the first book on the systematic solution of linear and quadratic equations. Latin translations of his Arithmetic, on the Indian numerals, introduced the decimal positional number system to the Western world in the 12th century. He revised and updated Ptolemy's Geography as well as writing several works on astronomy and astrology.

- Al-ʿAbbās ibn Saʿid al-Jawharī (c. 800 Baghdad? – c. 860 Baghdad?)

- Al-Jawharī was a mathematician who worked at the House of Wisdom in Baghdad. His most important work was his Commentary on Euclid's Elements which contained nearly 50 additional propositions and an attempted proof of the parallel postulate.

- ʿAbd al-Hamīd ibn Turk (fl. 830 Baghdad)

- Ibn Turk wrote a work on algebra of which only a chapter on the solution of quadratic equations has survived.

- Yaʿqūb ibn Isḥāq al-Kindī (c. 801 Kufah – 873 Baghdad)

- Al-Kindī (or Alkindus) was a philosopher and scientist who worked as the House of Wisdom in Baghdad where he wrote commentaries on many Greek works. His contributions to mathematics include many works on arithmetic and geometry.

- Hunayn ibn Ishaq (808 Al-Hirah – 873 Baghdad)

- Hunayn (or Johannitus) was a translator who worked at the House of Wisdom in Baghdad. Translated many Greek works including those by Plato, Aristotle, Galen, Hippocrates, and the Neoplatonists.

- Banū Mūsā (c. 800 Baghdad – 873+ Baghdad)

- The Banū Mūsā were three brothers who worked at the House of Wisdom in Baghdad. Their most famous mathematical treatise is The Book of the Measurement of Plane and Spherical Figures, which considered similar problems as Archimedes did in his On the Measurement of the Circle and On the sphere and the cylinder. They contributed individually as well. The eldest, Jaʿfar Muḥammad (c. 800) specialised in geometry and astronomy. He wrote a critical revision on Apollonius' Conics called Premises of the book of conics. Aḥmad (c. 805) specialised in mechanics and wrote a work on pneumatic devices called On mechanics. The youngest, al-Ḥasan (c. 810) specialised in geometry and wrote a work on the ellipse called The elongated circular figure.

- Al-Mahani

- Ahmed ibn Yusuf

- Thabit ibn Qurra (Syria-Iraq, 835-901)

- Al-Hashimi (Iraq? ca. 850-900)

- Muḥammad ibn Jābir al-Ḥarrānī al-Battānī (c. 853 Harran – 929 Qasr al-Jiss near Samarra)

- Abu Kamil (Egypt? ca. 900)

- Sinan ibn Tabit (ca. 880 - 943)

- Al-Nayrizi

- Ibrahim ibn Sinan (Iraq, 909-946)

- Al-Khazin (Iraq-Iran, ca. 920-980)

- Al-Karabisi (Iraq? 10th century?)

- Ikhwan al-Safa' (Iraq, first half of 10th century)

- The Ikhwan al-Safa' ("brethren of purity") were a (mystical?) group in the city of Basra in Irak. The group authored a series of more than 50 letters on science, philosophy and theology. The first letter is on arithmetic and number theory, the second letter on geometry.

- Al-Uqlidisi (Iraq-Iran, 10th century)

- Al-Saghani (Iraq-Iran, ca. 940-1000)

- Abū Sahl al-Qūhī (Iraq-Iran, ca. 940-1000)

- Al-Khujandi

- Abū al-Wafāʾ al-Būzjānī (Iraq-Iran, ca. 940-998)

- Ibn Sahl (Iraq-Iran, ca. 940-1000)

- Al-Sijzi (Iran, ca. 940-1000)

- Labana of Cordoba (Spain, ca. 10th century)

- One of the few Islamic female mathematicians known by name, and the secretary of the Umayyad Caliph al-Hakem II. She was well-versed in the exact sciences, and could solve the most complex geometrical and algebraic problems known in her time.[20]

- Ibn Yunus (Egypt, ca. 950-1010)

- Abu Nasr ibn `Iraq (Iraq-Iran, ca. 950-1030)

- Kushyar ibn Labban (Iran, ca. 960-1010)

- Al-Karaji (Iran, ca. 970-1030)

- Ibn al-Haytham (Iraq-Egypt, ca. 965-1040)

- Abū al-Rayḥān al-Bīrūnī (September 15 973 in Kath, Khwarezm – December 13 1048 in Gazna)

- Ibn Sina

- al-Baghdadi

- Al-Nasawi

- Al-Jayyani (Spain, ca. 1030-1090)

- Ibn al-Zarqalluh (Azarquiel, al-Zarqali) (Spain, ca. 1030-1090)

- Al-Mu'taman ibn Hud (Spain, ca. 1080)

- al-Khayyam (Iran, ca. 1050-1130)

- Ibn Yaḥyā al-Maghribī al-Samawʾal (ca. 1130, Baghdad – c. 1180, Maragha)

- Al-Hassār (ca. 1100s, Maghreb)

- Developed the modern mathematical notation for fractions and the digits he uses for the ghubar numerals also cloesly resembles modern Western Arabic numerals.

- Ibn al-Yāsamīn (ca. 1100s, Maghreb)

- The son of a Berber father and black African mother, he was the first to develop a mathematical notation for algebra since the time of Brahmagupta.

- Sharaf al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī (Iran, ca. 1150-1215)

- Ibn Mun`im (Maghreb, ca. 1210)

- al-Marrakushi (Morocco, 13th century)

- Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī (18 February 1201 in Tus, Khorasan – 26 June 1274 in Kadhimain near Baghdad)

- Muḥyi al-Dīn al-Maghribī (c. 1220 Spain – c. 1283 Maragha)

- Shams al-Dīn al-Samarqandī (c. 1250 Samarqand – c. 1310)

- Ibn Baso (Spain, ca. 1250-1320)

- Ibn al-Banna' (Maghreb, ca. 1300)

- Kamal al-Din Al-Farisi (Iran, ca. 1300)

- Al-Khalili (Syria, ca. 1350-1400)

- Ibn al-Shatir (1306-1375)

- Qāḍī Zāda al-Rūmī (1364 Bursa – 1436 Samarkand)

- Jamshīd al-Kāshī (Iran, Uzbekistan, ca. 1420)

- Ulugh Beg (Iran, Uzbekistan, 1394-1449)

- Al-Umawi

- Abū al-Hasan ibn Alī al-Qalasādī (Maghreb, 1412-1482)

- Last major medieval Arab mathematician. Pioneer of symbolic algebra.

Algebra

The term algebra is derived from the Arabic term al-jabr in the title of Al-Khwarizmi's Al-jabr wa'l muqabalah. He originally used the term al-jabr to describe the method of "reduction" and "balancing", referring to the transposition of subtracted terms to the other side of an equation, that is, the cancellation of like terms on opposite sides of the equation.[21]

There are three theories about the origins of Arabic algebra. The first emphasizes Hindu influence, the second emphasizes Mesopotamian or Persian-Syriac influence, and the third emphasizes Greek influence. Many scholars believe that it is the result of a combination of all three sources.[22]

Throughout their time in power, before the fall of Islamic civilization, the Arabs used a fully rhetorical algebra, where sometimes even the numbers were spelled out in words. The Arabs would eventually replace spelled out numbers (eg. twenty-two) with Arabic numerals (eg. 22), but the Arabs never adopted or developed a syncopated or symbolic algebra,[5] until the work of Ibn al-Banna al-Marrakushi in the 13th century and Abū al-Hasan ibn Alī al-Qalasādī in the 15th century.[13]

There were four conceptual stages in the development of algebra, three of which either began in, or were significantly advanced in, the Islamic world. These four stages were as follows:[23]

- Geometric stage, where the concepts of algebra are largely geometric. This dates back to the Babylonians and continued with the Greeks, and was revived by Omar Khayyam.

- Static equation-solving stage, where the objective is to find numbers satisfying certain relationships. The move away from geometric algebra dates back to Diophantus and Brahmagupta, but algebra didn't decisively move to the static equation-solving stage until Al-Khwarizmi's Al-Jabr.

- Dynamic function stage, where motion is an underlying idea. The idea of a function began emerging with Sharaf al-Dīn al-Tūsī, but algebra didn't decisively move to the dynamic function stage until Gottfried Leibniz.

- Abstract stage, where mathematical structure plays a central role. Abstract algebra is largely a product of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Static equation-solving algebra

- Al-Khwarizmi and Al-jabr wa'l muqabalah

The Muslim[24] Persian mathematician Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī (c. 780-850) was a faculty member of the "House of Wisdom" (Bait al-hikma) in Baghdad, which was established by Al-Mamun. Al-Khwarizmi, who died around 850 A.D., wrote more than half a dozen mathematical and astronomical works; some of which were based on the Indian Sindhind.[4] One of al-Khwarizmi's most famous books is entitled Al-jabr wa'l muqabalah or The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing, and it gives an exhaustive account of solving polynomials up to the second degree.[25] The book also introduced the fundamental method of "reduction" and "balancing", referring to the transposition of subtracted terms to the other side of an equation, that is, the cancellation of like terms on opposite sides of the equation. This is the operation which Al-Khwarizmi originally described as al-jabr.[21]

Al-Jabr is divided into six chapters, each of which deals with a different type of formula. The first chapter of Al-Jabr deals with equations whose squares equal its roots (ax² = bx), the second chapter deals with squares equal to number (ax² = c), the third chapter deals with roots equal to a number (bx = c), the fourth chapter deals with squares and roots equal a number (ax² + bx = c), the fifth chapter deals with squares and number equal roots (ax² + c = bx), and the sixth and final chapter deals with roots and number equal to squares (bx + c = ax²).[26]

J. J. O'Conner and E. F. Robertson wrote in the MacTutor History of Mathematics archive:

"Perhaps one of the most significant advances made by Arabic mathematics began at this time with the work of al-Khwarizmi, namely the beginnings of algebra. It is important to understand just how significant this new idea was. It was a revolutionary move away from the Greek concept of mathematics which was essentially geometry. Algebra was a unifying theory which allowed rational numbers, irrational numbers, geometrical magnitudes, etc., to all be treated as "algebraic objects". It gave mathematics a whole new development path so much broader in concept to that which had existed before, and provided a vehicle for future development of the subject. Another important aspect of the introduction of algebraic ideas was that it allowed mathematics to be applied to itself in a way which had not happened before."

The Hellenistic mathematician Diophantus was traditionally known as "the father of algebra"[27][28] but debate now exists as to whether or not Al-Khwarizmi deserves this title instead.[27] Those who support Diophantus point to the fact that the algebra found in Al-Jabr is more elementary than the algebra found in Arithmetica and that Arithmetica is syncopated while Al-Jabr is fully rhetorical.[27] Those who support Al-Khwarizmi point to the fact that he gave an exhaustive explanation for the algebraic solution of quadratic equations with positive roots,[29] was the first to teach algebra in an elementary form and for its own sake, whereas Diophantus was primarily concerned with the theory of numbers.[30] R. Rashed and Angela Armstrong write:

"Al-Khwarizmi's text can be seen to be distinct not only from the Babylonian tablets, but also from Diophantus' Arithmetica. It no longer concerns a series of problems to be resolved, but an exposition which starts with primitive terms in which the combinations must give all possible prototypes for equations, which henceforward explicitly constitute the true object of study. On the other hand, the idea of an equation for its own sake appears from the beginning and, one could say, in a generic manner, insofar as it does not simply emerge in the course of solving a problem, but is specifically called on to define an infinite class of problems."[31]

- Logical Necessities in Mixed Equations

'Abd al-Hamīd ibn Turk (fl. 830) authored a manuscript entitled Logical Necessities in Mixed Equations, which is very similar to al-Khwarzimi's Al-Jabr and was published at around the same time as, or even possibly earlier than, Al-Jabr.[32] The manuscript gives the exact same geometric demonstration as is found in Al-Jabr, and in one case the same example as found in Al-Jabr, and even goes beyond Al-Jabr by giving a geometric proof that if the determinant is negative then the quadratic equation has no solution.[32] The similarity between these two works has led some historians to conclude that Arabic algebra may have been well developed by the time of al-Khwarizmi and 'Abd al-Hamid.[32]

- Abū Kāmil and al-Karkhi

Arabic mathematicians were also the first to treat irrational numbers as algebraic objects.[33] The Egyptian mathematician Abū Kāmil Shujā ibn Aslam (c. 850-930) was the first to accept irrational numbers (often in the form of a square root, cube root or fourth root) as solutions to quadratic equations or as coefficients in an equation.[34] He was also the first to solve three non-linear simultaneous equations with three unknown variables.[35]

Al-Karkhi (953-1029), also known as Al-Karaji, was the successor of Abū al-Wafā' al-Būzjānī (940-998) and he was the first to discover the solution to equations of the form ax2n + bxn = c.[36] Al-Karkhi only considered positive roots.[36] Al-Karkhi is also regarded as the first person to free algebra from geometrical operations and replace them with the type of arithmetic operations which are at the core of algebra today. His work on algebra and polynomials, gave the rules for arithmetic operations to manipulate polynomials. The historian of mathematics F. Woepcke, in Extrait du Fakhri, traité d'Algèbre par Abou Bekr Mohammed Ben Alhacan Alkarkhi (Paris, 1853), praised Al-Karaji for being "the first who introduced the theory of algebraic calculus". Stemming from this, Al-Karaji investigated binomial coefficients and Pascal's triangle.[37]

Linear algebra

In linear algebra and recreational mathematics, magic squares were known to Arab mathematicians, possibly as early as the 7th century, when the Arabs got into contact with Indian or South Asian culture, and learned Indian mathematics and astronomy, including other aspects of combinatorial mathematics. It has also been suggested that the idea came via China. The first magic squares of order 5 and 6 appear in an encyclopedia from Baghdad circa 983 AD, the Rasa'il Ihkwan al-Safa (Encyclopedia of the Brethren of Purity); simpler magic squares were known to several earlier Arab mathematicians.[38]

The Arab mathematician Ahmad al-Buni, who worked on magic squares around 1200 AD, attributed mystical properties to them, although no details of these supposed properties are known. There are also references to the use of magic squares in astrological calculations, a practice that seems to have originated with the Arabs.[38]

Geometric algebra

Omar Khayyám (c. 1050-1123) wrote a book on Algebra that went beyond Al-Jabr to include equations of the third degree.[39] Omar Khayyám provided both arithmetic and geometric solutions for quadratic equations, but he only gave geometric solutions for general cubic equations since he mistakenly believed that arithmetic solutions were impossible.[39] His method of solving cubic equations by using intersecting conics had been used by Menaechmus, Archimedes, and Alhazen, but Omar Khayyám generalized the method to cover all cubic equations with positive roots.[39] He only considered positive roots and he did not go past the third degree.[39] He also saw a strong relationship between Geometry and Algebra.[39]

Dynamic functional algebra

In the 12th century, Sharaf al-Dīn al-Tūsī found algebraic and numerical solutions to cubic equations and was the first to discover the derivative of cubic polynomials.[40] His Treatise on Equations dealt with equations up to the third degree. The treatise does not follow Al-Karaji's school of algebra, but instead represents "an essential contribution to another algebra which aimed to study curves by means of equations, thus inaugurating the beginning of algebraic geometry." The treatise dealt with 25 types of equations, including twelve types of linear equations and quadratic equations, eight types of cubic equations with positive solutions, and five types of cubic equations which may not have positive solutions.[41] He understood the importance of the discriminant of the cubic equation and used an early version of Cardano's formula[42] to find algebraic solutions to certain types of cubic equations.[40]

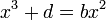

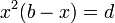

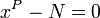

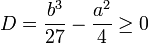

Sharaf al-Din also developed the concept of a function. In his analysis of the equation  for example, he begins by changing the equation's form to

for example, he begins by changing the equation's form to  . He then states that the question of whether the equation has a solution depends on whether or not the “function” on the left side reaches the value

. He then states that the question of whether the equation has a solution depends on whether or not the “function” on the left side reaches the value  . To determine this, he finds a maximum value for the function. He proves that the maximum value occurs when

. To determine this, he finds a maximum value for the function. He proves that the maximum value occurs when  , which gives the functional value

, which gives the functional value  . Sharaf al-Din then states that if this value is less than

. Sharaf al-Din then states that if this value is less than  , there are no positive solutions; if it is equal to

, there are no positive solutions; if it is equal to  , then there is one solution at

, then there is one solution at  ; and if it is greater than

; and if it is greater than  , then there are two solutions, one between

, then there are two solutions, one between  and

and  and one between

and one between  and

and  . This was the earliest form of dynamic functional algebra.[43]

. This was the earliest form of dynamic functional algebra.[43]

Numerical analysis

In numerical analysis, the essence of Viète's method was known to Sharaf al-Dīn al-Tūsī in the 12th century, and it is possible that the algebraic tradition of Sharaf al-Dīn, as well as his predecessor Omar Khayyám and successor Jamshīd al-Kāshī, was known to 16th century European algebraists, or whom François Viète was the most important.[44]

A method algebraically equivalent to Newton's method was also known to Sharaf al-Dīn. In the 15th century, his successor al-Kashi later used a form of Newton's method to numerically solve  to find roots of

to find roots of  . In western Europe, a similar method was later described by Henry Biggs in his Trigonometria Britannica, published in 1633.[45]

. In western Europe, a similar method was later described by Henry Biggs in his Trigonometria Britannica, published in 1633.[45]

Symbolic algebra

Al-Hassār, a mathematician from the Maghreb (North Africa) specializing in Islamic inheritance jurisprudence during the 12th century, developed the modern symbolic mathematical notation for fractions, where the numerator and denominator are separated by a horizontal bar. This same fractional notation appeared soon after in the work of Fibonacci in the 13th century.[12]

Abū al-Hasan ibn Alī al-Qalasādī (1412-1482) was the last major medieval Arab algebraist, who improved on the algebraic notation earlier used in the Maghreb by Ibn al-Banna in the 13th century[13] and by Ibn al-Yāsamīn in the 12th century.[12] In contrast to the syncopated notations of their predecessors, Diophantus and Brahmagupta, which lacked symbols for mathematical operations,[46] al-Qalasadi's algebraic notation was the first to have symbols for these functions and was thus "the first steps toward the introduction of algebraic symbolism." He represented mathematical symbols using characters from the Arabic alphabet.[13]

The symbol  now commonly denotes an unknown variable. Even though any letter can be used,

now commonly denotes an unknown variable. Even though any letter can be used,  is the most common choice. This usage can be traced back to the Arabic word šay' شيء = “thing,” used in Arabic algebra texts such as the Al-Jabr, and was taken into Old Spanish with the pronunciation “šei,” which was written xei, and was soon habitually abbreviated to

is the most common choice. This usage can be traced back to the Arabic word šay' شيء = “thing,” used in Arabic algebra texts such as the Al-Jabr, and was taken into Old Spanish with the pronunciation “šei,” which was written xei, and was soon habitually abbreviated to  . (The Spanish pronunciation of “x” has changed since). Some sources say that this

. (The Spanish pronunciation of “x” has changed since). Some sources say that this  is an abbreviation of Latin causa, which was a translation of Arabic شيء. This started the habit of using letters to represent quantities in algebra. In mathematics, an “italicized x” (

is an abbreviation of Latin causa, which was a translation of Arabic شيء. This started the habit of using letters to represent quantities in algebra. In mathematics, an “italicized x” ( ) is often used to avoid potential confusion with the multiplication symbol.

) is often used to avoid potential confusion with the multiplication symbol.

Arithmetic

Arabic numerals

- See also: Arabic numerals

The Indian numeral system came to be known to both the Persian mathematician Al-Khwarizmi, whose book On the Calculation with Hindu Numerals written circa 825, and the Arab mathematician Al-Kindi, who wrote four volumes, On the Use of the Indian Numerals (Ketab fi Isti'mal al-'Adad al-Hindi) circa 830, are principally responsible for the diffusion of the Indian system of numeration in the Middle-East and the West [3]. In the 10th century, Middle-Eastern mathematicians extended the decimal numeral system to include fractions using decimal point notation, as recorded in a treatise by Syrian mathematician Abu'l-Hasan al-Uqlidisi in 952-953.

In the Arab world—until early modern times—the Arabic numeral system was often only used by mathematicians. Muslim astronomers mostly used the Babylonian numeral system, and merchants mostly used the Abjad numerals. A distinctive "Western Arabic" variant of the symbols begins to emerge in ca. the 10th century in the Maghreb and Al-Andalus, called the ghubar ("sand-table" or "dust-table") numerals, which is the direct ancestor to the modern Western Arabic numerals now used throughout the world.[47]

The first mentions of the numerals in the West are found in the Codex Vigilanus of 976 [4]. From the 980s, Gerbert of Aurillac (later, Pope Silvester II) began to spread knowledge of the numerals in Europe. Gerbert studied in Barcelona in his youth, and he is known to have requested mathematical treatises concerning the astrolabe from Lupitus of Barcelona after he had returned to France.

Al-Khwārizmī, the Persian scientist, wrote in 825 a treatise On the Calculation with Hindu Numerals, which was translated into Latin in the 12th century, as Algoritmi de numero Indorum, where "Algoritmi", the translator's rendition of the author's name gave rise to the word algorithm (Latin algorithmus) with a meaning "calculation method".

Al-Hassār, a mathematician from the Maghreb (North Africa) specializing in Islamic inheritance jurisprudence during the 12th century, developed the modern symbolic mathematical notation for fractions, where the numerator and denominator are separated by a horizontal bar. The "dust ciphers he used are also nearly identical to the digits used in the current Western Arabic numerals. These same digits and fractional notation appear soon after in the work of Fibonacci in the 13th century.[12]

Decimal fractions

In discussing the origins of decimal fractions, Dirk Jan Struik states that (p. 7):[48]

"The introduction of decimal fractions as a common computational practice can be dated back to the Flemish pamphelet De Thiende, published at Leyden in 1585, together with a French translation, La Disme, by the Flemish mathematician Simon Stevin (1548-1620), then settled in the Northern Netherlands. It is true that decimal fractions were used by the Chinese many centuries before Stevin and that the Persian astronomer Al-Kāshī used both decimal and sexagesimal fractions with great ease in his Key to arithmetic (Samarkand, early fifteenth century).[49]"

While the Persian mathematician Jamshīd al-Kāshī claimed to have discovered decimal fractions himself in the 15th century, J. Lennart Berggrenn notes that he was mistaken, as decimal fractions were first used five centuries before him by the Baghdadi mathematician Abu'l-Hasan al-Uqlidisi as early as the 10th century.[35]

Real numbers

The Middle Ages saw the acceptance of zero, negative, integral and fractional numbers, first by Indian mathematicians and Chinese mathematicians, and then by Arabic mathematicians, who were also the first to treat irrational numbers as algebraic objects,[50] which was made possible by the development of algebra. Arabic mathematicians merged the concepts of "number" and "magnitude" into a more general idea of real numbers, and they criticized Euclid's idea of ratios, developed the theory of composite ratios, and extended the concept of number to ratios of continuous magnitude.[51] In his commentary on Book 10 of the Elements, the Persian mathematician Al-Mahani (d. 874/884) examined and classified quadratic irrationals and cubic irrationals. He provided definitions for rational and irrational magnitudes, which he treated as irrational numbers. He dealt with them freely but explains them in geometric terms as follows:[52]

"It will be a rational (magnitude) when we, for instance, say 10, 12, 3%, 6%, etc., because its value is pronounced and expressed quantitatively. What is not rational is irrational and it is impossible to pronounce and represent its value quantitatively. For example: the roots of numbers such as 10, 15, 20 which are not squares, the sides of numbers which are not cubes etc."

In contrast to Euclid's concept of magnitudes as lines, Al-Mahani considered integers and fractions as rational magnitudes, and square roots and cube roots as irrational magnitudes. He also introduced an arithmetical approach to the concept of irrationality, as he attributes the following to irrational magnitudes:[52]

"their sums or differences, or results of their addition to a rational magnitude, or results of subtracting a magnitude of this kind from an irrational one, or of a rational magnitude from it."

The Egyptian mathematician Abū Kāmil Shujā ibn Aslam (c. 850–930) was the first to accept irrational numbers as solutions to quadratic equations or as coefficients in an equation, often in the form of square roots, cube roots and fourth roots.[34] In the 10th century, the Iraqi mathematician Al-Hashimi provided general proofs (rather than geometric demonstrations) for irrational numbers, as he considered multiplication, division, and other arithmetical functions.[53] Abū Ja'far al-Khāzin (900-971) provides a definition of rational and irrational magnitudes, stating that if a definite quantity is:[54]

"contained in a certain given magnitude once or many times, then this (given) magnitude corresponds to a rational number. . . . Each time when this (latter) magnitude comprises a half, or a third, or a quarter of the given magnitude (of the unit), or, compared with (the unit), comprises three, five, or three fifths, it is a rational magnitude. And, in general, each magnitude that corresponds to this magnitude (i.e. to the unit), as one number to another, is rational. If, however, a magnitude cannot be represented as a multiple, a part (l/n), or parts (m/n) of a given magnitude, it is irrational, i.e. it cannot be expressed other than by means of roots."

Many of these concepts were eventually accepted by European mathematicians some time after the Latin translations of the 12th century. Al-Hassār, an Arabic mathematician from the Maghreb (North Africa) specializing in Islamic inheritance jurisprudence during the 12th century, developed the modern symbolic mathematical notation for fractions, where the numerator and denominator are separated by a horizontal bar. This same fractional notation appears soon after in the work of Fibonacci in the 13th century.[55]

Number theory

In number theory, Ibn al-Haytham solved problems involving congruences using what is now called Wilson's theorem. In his Opuscula, Ibn al-Haytham considers the solution of a system of congruences, and gives two general methods of solution. His first method, the canonical method, involved Wilson's theorem, while his second method involved a version of the Chinese remainder theorem. Another contribution to number theory is his work on perfect numbers. In his Analysis and synthesis, Ibn al-Haytham was the first to discover that every even perfect number is of the form 2n−1(2n − 1) where 2n − 1 is prime, but he was not able to prove this result successfully (Euler later proved it in the 18th century).[56]

In the early 14th century, Kamāl al-Dīn al-Fārisī made a number of important contributions to number theory. His most impressive work in number theory is on amicable numbers. In Tadhkira al-ahbab fi bayan al-tahabb ("Memorandum for friends on the proof of amicability") introduced a major new approach to a whole area of number theory, introducing ideas concerning factorization and combinatorial methods. In fact, al-Farisi's approach is based on the unique factorization of an integer into powers of prime numbers.

Geometry

The successors of Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī (born 780) undertook a systematic application of arithmetic to algebra, algebra to arithmetic, both to trigonometry, algebra to the Euclidean theory of numbers, algebra to geometry, and geometry to algebra. This was how the creation of polynomial algebra, combinatorial analysis, numerical analysis, the numerical solution of equations, the new elementary theory of numbers, and the geometric construction of equations arose.

Al-Mahani (born 820) conceived the idea of reducing geometrical problems such as duplicating the cube to problems in algebra. Al-Karaji (born 953) completely freed algebra from geometrical operations and replaced them with the arithmetical type of operations which are at the core of algebra today.

Early Islamic geometry

- See also Applied mathematics

Thabit ibn Qurra (known as Thebit in Latin) (born 836) contributed to a number of areas in mathematics, where he played an important role in preparing the way for such important mathematical discoveries as the extension of the concept of number to (positive) real numbers, integral calculus, theorems in spherical trigonometry, analytic geometry, and non-Euclidean geometry. An important geometrical aspect of Thabit's work was his book on the composition of ratios. In this book, Thabit deals with arithmetical operations applied to ratios of geometrical quantities. The Greeks had dealt with geometric quantities but had not thought of them in the same way as numbers to which the usual rules of arithmetic could be applied. By introducing arithmetical operations on quantities previously regarded as geometric and non-numerical, Thabit started a trend which led eventually to the generalization of the number concept. Another important contribution Thabit made to geometry was his generalization of the Pythagorean theorem, which he extended from special right triangles to all right triangles in general, along with a general proof.[57]

In some respects, Thabit is critical of the ideas of Plato and Aristotle, particularly regarding motion. It would seem that here his ideas are based on an acceptance of using arguments concerning motion in his geometrical arguments. Another important contribution Thabit made to geometry was his generalization of the Pythagorean theorem, which he extended from special right triangles to all triangles in general, along with a general proof.[57]

Ibrahim ibn Sinan ibn Thabit (born 908), who introduced a method of integration more general than that of Archimedes, and al-Quhi (born 940) were leading figures in a revival and continuation of Greek higher geometry in the Islamic world. These mathematicians, and in particular Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen), studied optics and investigated the optical properties of mirrors made from conic sections (see Mathematical physics).

Astronomy, time-keeping and geography provided other motivations for geometrical and trigonometrical research. For example Ibrahim ibn Sinan and his grandfather Thabit ibn Qurra both studied curves required in the construction of sundials. Abu'l-Wafa and Abu Nasr Mansur pioneered spherical geometry in order to solve difficult problems in Islamic astronomy. For example, to predict the first visibility of the moon, it was necessary to describe its motion with respect to the horizon, and this problem demands fairly sophisticated spherical geometry. Finding the direction of Mecca (Qibla) and the time for Salah prayers and Ramadan are what led to Muslims developing spherical geometry.[10][17]

Algebraic and analytic geometry

In the early 11th century, Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) was able to solve by purely algebraic means certain cubic equations, and then to interpret the results geometrically.[58] Subsequently, Omar Khayyám discovered the general method of solving cubic equations by intersecting a parabola with a circle.[59]

Omar Khayyám (1048-1122) was a Persian mathematician, as well as a poet. Along with his fame as a poet, he was also famous during his lifetime as a mathematician, well known for inventing the general method of solving cubic equations by intersecting a parabola with a circle. In addition he discovered the binomial expansion, and authored criticisms of Euclid's theories of parallels which made their way to England, where they contributed to the eventual development of non-Euclidean geometry. Omar Khayyam also combined the use of trigonometry and approximation theory to provide methods of solving algebraic equations by geometrical means. His work marked the beginnings of algebraic geometry[60][61] and analytic geometry.[62]

In a paper written by Khayyam before his famous algebra text Treatise on Demonstration of Problems of Algebra, he considers the problem: Find a point on a quadrant of a circle in such manner that when a normal is dropped from the point to one of the bounding radii, the ratio of the normal's length to that of the radius equals the ratio of the segments determined by the foot of the normal. Khayyam shows that this problem is equivalent to solving a second problem: Find a right triangle having the property that the hypotenuse equals the sum of one leg plus the altitude on the hypotenuse. This problem in turn led Khayyam to solve the cubic equation x3 + 200x = 20x2 + 2000 and he found a positive root of this cubic by considering the intersection of a rectangular hyperbola and a circle. An approximate numerical solution was then found by interpolation in trigonometric tables. Perhaps even more remarkable is the fact that Khayyam states that the solution of this cubic requires the use of conic sections and that it cannot be solved by compass and straightedge, a result which would not be proved for another 750 years.

His Treatise on Demonstration of Problems of Algebra contained a complete classification of cubic equations with geometric solutions found by means of intersecting conic sections. In fact Khayyam gives an interesting historical account in which he claims that the Greeks had left nothing on the theory of cubic equations. Indeed, as Khayyam writes, the contributions by earlier writers such as al-Mahani and al-Khazin were to translate geometric problems into algebraic equations (something which was essentially impossible before the work of Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Ḵwārizmī). However, Khayyam himself seems to have been the first to conceive a general theory of cubic equations.

Omar Khayyám saw a strong relationship between geometry and algebra, and was moving in the right direction when he helped to close the gap between numerical and geometric algebra[39] with his geometric solution of the general cubic equations,[62] but the decisive step in analytic geometry came later with René Descartes.[39]

Persian mathematician Sharafeddin Tusi (born 1135) did not follow the general development that came through al-Karaji's school of algebra but rather followed Khayyam's application of algebra to geometry. He wrote a treatise on cubic equations, entitled Treatise on Equations, which represents an essential contribution to another algebra which aimed to study curves by means of equations, thus inaugurating the study of algebraic geometry.[41]

Non-Euclidean geometry

In the early 11th century, Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) made the first attempt at proving the Euclidean parallel postulate, the fifth postulate in Euclid's Elements, using a proof by contradiction,[63] where he introduced the concept of motion and transformation into geometry.[64] He formulated the Lambert quadrilateral, which Boris Abramovich Rozenfeld names the "Ibn al-Haytham–Lambert quadrilateral",[65] and his attempted proof also shows similarities to Playfair's axiom.[66]

In the late 11th century, Omar Khayyám made the first attempt at formulating a non-Euclidean postulate as an alternative to the Euclidean parallel postulate,[67] and he was the first to consider the cases of elliptical geometry and hyperbolic geometry, though he excluded the latter.[68]

In Commentaries on the difficult postulates of Euclid's book Khayyam made a contribution to non-Euclidean geometry, although this was not his intention. In trying to prove the parallel postulate he accidentally proved properties of figures in non-Euclidean geometries. Khayyam also gave important results on ratios in this book, extending Euclid's work to include the multiplication of ratios. The importance of Khayyam's contribution is that he examined both Euclid's definition of equality of ratios (which was that first proposed by Eudoxus) and the definition of equality of ratios as proposed by earlier Islamic mathematicians such as al-Mahani which was based on continued fractions. Khayyam proved that the two definitions are equivalent. He also posed the question of whether a ratio can be regarded as a number but leaves the question unanswered.

The Khayyam-Saccheri quadrilateral was first considered by Omar Khayyam in the late 11th century in Book I of Explanations of the Difficulties in the Postulates of Euclid.[65] Unlike many commentators on Euclid before and after him (including of course Saccheri), Khayyam was not trying to prove the parallel postulate as such but to derive it from an equivalent postulate he formulated from "the principles of the Philosopher" (Aristotle):

- Two convergent straight lines intersect and it is impossible for two convergent straight lines to diverge in the direction in which they converge.[69]

Khayyam then considered the three cases right, obtuse, and acute that the summit angles of a Saccheri quadrilateral can take and after proving a number of theorems about them, he (correctly) refuted the obtuse and acute cases based on his postulate and hence derived the classic postulate of Euclid. It wasn't until 600 years later that Giordano Vitale made an advance on the understanding of this quadrilateral in his book Euclide restituo (1680, 1686), when he used it to prove that if three points are equidistant on the base AB and the summit CD, then AB and CD are everywhere equidistant. Saccheri himself based the whole of his long, heroic and ultimately flawed proof of the parallel postulate around the quadrilateral and its three cases, proving many theorems about its properties along the way.

In 1250, Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī, in his Al-risala al-shafiya'an al-shakk fi'l-khutut al-mutawaziya (Discussion Which Removes Doubt about Parallel Lines), wrote detailed critiques of the Euclidean parallel postulate and on Omar Khayyám's attempted proof a century earlier. Nasir al-Din attempted to derive a proof by contradiction of the parallel postulate.[70] He was one of the first to consider the cases of elliptical geometry and hyperbolic geometry, though he ruled out both of them.[68]

His son, Sadr al-Din (sometimes known as "Pseudo-Tusi"), wrote a book on the subject in 1298, based on al-Tusi's later thoughts, which presented one of the earliest arguments for a non-Euclidean hypothesis equivalent to the parallel postulate.[70][71] Sadr al-Din's work was published in Rome in 1594 and was studied by European geometers. This work marked the starting point for Giovanni Girolamo Saccheri's work on the subject, and eventually the development of modern non-Euclidean geometry.[70] A proof from Sadr al-Din's work was quoted by John Wallis and Saccheri in the 17th and 18th centuries. They both derived their proofs of the parallel postulate from Sadr al-Din's work, while Saccheri also derived his Saccheri quadrilateral from Sadr al-Din, who himself based it on his father's work.[72]

The theorems of Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen), Omar Khayyam and Nasir al-Din al-Tusi on quadrilaterals, including the Lambert quadrilateral and Saccheri quadrilateral, were the first theorems on elliptical geometry and hyperbolic geometry, and along with their alternative postulates, such as Playfair's axiom, these works marked the beginning of non-Euclidean geometry and had a considerable influence on its development among later European geometers, including Witelo, Levi ben Gerson, Alfonso, John Wallis, and Giovanni Girolamo Saccheri.[73]

Trigonometry

The early Indian works on trigonometry were translated and expanded in the Muslim world by Arab and Persian mathematicians. They enunciated a large number of theorems which freed the subject of trigonometry from dependence upon the complete quadrilateral, as was the case in Hellenistic mathematics due to the application of Menelaus' theorem. According to E. S. Kennedy, it was after this development in Islamic mathematics that "the first real trigonometry emerged, in the sense that only then did the object of study become the spherical or plane triangle, its sides and angles."[74]

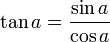

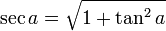

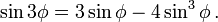

In the early 9th century, Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī (c. 780-850) produced tables for the trigonometric functions of sines and cosine, and the first tables for tangents. He was also an early pioneer in spherical trigonometry. In 830, Habash al-Hasib al-Marwazi produced the first tables of cotangents as well as tangents.[75][76] Muhammad ibn Jābir al-Harrānī al-Battānī (853-929) discovered the reciprocal functions of secant and cosecant, and produced the first table of cosecants, which he referred to as a "table of shadows" (in reference to the shadow of a gnomon), for each degree from 1° to 90°.[76] He also formulated a number of important trigonometrical relationships such as:

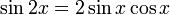

By the 10th century, in the work of Abū al-Wafā' al-Būzjānī (959-998), Muslim mathematicians were using all six trigonometric functions, and had sine tables in 0.25° increments, to 8 decimal places of accuracy, as well as tables of tangent values. Abū al-Wafā' also developed the following trigonometric formula:

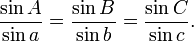

Abū al-Wafā also established the angle addition identities, e.g. sin (a + b), and discovered the law of sines for spherical trigonometry:[75]

Also in the late 10th and early 11th centuries, the Egyptian astronomer Ibn Yunus performed many careful trigonometric calculations and demonstrated the following formula:

Al-Jayyani (989–1079) of al-Andalus wrote The book of unknown arcs of a sphere, which is considered "the first treatise on spherical trigonometry" in its modern form,[77] although spherical trigonometry in its ancient Hellenistic form was dealt with by earlier mathematicians such as Menelaus of Alexandria, who developed Menelaus' theorem to deal with spherical problems.[78][79] However, E. S. Kennedy points out that while it was possible in pre-lslamic mathematics to compute the magnitudes of a spherical figure, in principle, by use of the table of chords and Menelaus' theorem, the application of the theorem to spherical problems was very difficult in practice.[80] Al-Jayyani's work on spherical trigonometry "contains formulae for right-handed triangles, the general law of sines, and the solution of a spherical triangle by means of the polar triangle." This treatise later had a "strong influence on European mathematics", and his "definition of ratios as numbers" and "method of solving a spherical triangle when all sides are unknown" are likely to have influenced Regiomontanus.[77]

The method of triangulation, which was unknown in the Greco-Roman world, was also first developed by Muslim mathematicians, who applied it to practical uses such as surveying[81] and Islamic geography, as described by Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī in the early 11th century.[82] In the late 11th century, Omar Khayyám (1048-1131) solved cubic equations using approximate numerical solutions found by interpolation in trigonometric tables. All of these earlier works on trigonometry treated it mainly as an adjunct to astronomy; the first treatment as a subject in its own right was by Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī in the 13th century. He also developed spherical trigonometry into its present form,[76] and listed the six distinct cases of a right-angled triangle in spherical trigonometry. In his On the Sector Figure, he also stated the law of sines for plane and spherical triangles, discovered the law of tangents for spherical triangles, and provided proofs for these laws.[35]

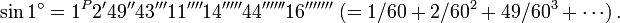

Jamshīd al-Kāshī (1393-1449) provided the first explicit statement of the law of cosines in a form suitable for triangulation. In France, the law of cosines is still referred to as the theorem of Al-Kashi. He also gives trigonometric tables of values of the sine function to four sexagesimal digits (equivalent to 8 decimal places) for each 1° of argument with differences to be added for each 1/60 of 1°.[83] In one of his numerical approximations of π, he correctly computed 2π to 9 sexagesimal digits.[84] In order to determine sin 1°, al-Kashi discovered the following triple-angle formula often attributed to François Viète in the 16th century:[85]

In French, the law of cosines is named Théorème d'Al-Kashi (Theorem of Al-Kashi), as al-Kashi was the first to provide an explicit statement of the law of cosines in a form suitable for triangulation. His colleague Ulugh Beg (1394-1449) gave accurate tables of sines and tangents correct to 8 decimal places.

Taqi al-Din (1526-1585) contributed to trigonometry in his Sidrat al-Muntaha, in which he was the first mathematician to compute a highly accurate numeric value for sin 1°. He discusses the values given by his predecessors, explaining how Ptolemy (ca. 150) used an approximate method to obtain his value of sin 1° and how Abū al-Wafā, Ibn Yunus (ca. 1000), al-Kashi, Qāḍī Zāda al-Rūmī (1337-1412), Ulugh Beg and Mirim Chelebi improved on the value. Taqi al-Din then solves the problem to obtain the value of sin 1° to a precision of 8 sexagesimals (the equivalent of 14 decimals):[86]

Calculus

Integral calculus

Around 1000 AD, Al-Karaji, using mathematical induction, found a proof for the sum of integral cubes.[87] The historian of mathematics, F. Woepcke,[88] praised Al-Karaji for being "the first who introduced the theory of algebraic calculus." Shortly afterwards, Ibn al-Haytham (known as Alhazen in the West), an Iraqi mathematician working in Egypt, was the first mathematician to derive the formula for the sum of the fourth powers, and using an early proof by mathematical induction, he developed a method for determining the general formula for the sum of any integral powers. He used his result on sums of integral powers to perform an integration, in order to find the volume of a paraboloid. He was thus able to find the integrals for polynomials up to the fourth degree, and came close to finding a general formula for the integrals of any polynomials. This was fundamental to the development of infinitesimal and integral calculus. His results were repeated by the Moroccan mathematicians Abu-l-Hasan ibn Haydur (d. 1413) and Abu Abdallah ibn Ghazi (1437-1514), by Jamshīd al-Kāshī (c. 1380-1429) in The Calculator's Key, and by the Indian mathematicians of the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics in the 15th-16th centuries.[70]

Differential calculus

In the 12th century, the Persian mathematician Sharaf al-Dīn al-Tūsī was the first to discover the derivative of cubic polynomials, an important result in differential calculus.[40] His Treatise on Equations developed concepts related to differential calculus, such as the derivative function and the maxima and minima of curves, in order to solve cubic equations which may not have positive solutions. For example, in order to solve the equation  , al-Tusi finds the maximum point of the curve

, al-Tusi finds the maximum point of the curve  . He uses the derivative of the function to find that the maximum point occurs at

. He uses the derivative of the function to find that the maximum point occurs at  , and then finds the maximum value for y at

, and then finds the maximum value for y at  by substituting

by substituting  back into

back into  . He finds that the equation

. He finds that the equation  has a solution if

has a solution if  , and al-Tusi thus deduces that the equation has a positive root if

, and al-Tusi thus deduces that the equation has a positive root if  , where

, where  is the discriminant of the equation.[41]

is the discriminant of the equation.[41]

Applied mathematics

Geometric art and architecture

Geometric artwork in the form of the Arabesque was not widely used in the Middle East or Mediterranean Basin until the golden age of Islam came into full bloom, when Arabesque became a common feature of Islamic art. Euclidean geometry as expounded on by Al-Abbās ibn Said al-Jawharī (ca. 800-860) in his Commentary on Euclid's Elements, the trigonometry of Aryabhata and Brahmagupta as elaborated on by Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī (ca. 780-850), and the development of spherical geometry[10] by Abū al-Wafā' al-Būzjānī (940–998) and spherical trigonometry by Al-Jayyani (989-1079)[89] for determining the Qibla and times of Salah and Ramadan,[10] all served as an impetus for the art form that was to become the Arabesque.

Recent discoveries have shown that geometrical quasicrystal patterns were first employed in the girih tiles found in medieval Islamic architecture dating back over five centuries ago. In 2007, Professor Peter Lu of Harvard University and Professor Paul Steinhardt of Princeton University published a paper in the journal Science suggesting that girih tilings possessed properties consistent with self-similar fractal quasicrystalline tilings such as the Penrose tilings, predating them by five centuries.[90][91]

Mathematical astronomy

An impetus behind mathematical astronomy came from Islamic religious observances, which presented a host of problems in mathematical astronomy, particularly in spherical geometry. In solving these religious problems the Islamic scholars went far beyond the Greek mathematical methods.[10] For example, predicting just when the crescent moon would become visible is a special challenge to Islamic mathematical astronomers. Although Ptolemy's theory of the complex lunar motion was tolerably accurate near the time of the new moon, it specified the moon's path only with respect to the ecliptic. To predict the first visibility of the moon, it was necessary to describe its motion with respect to the horizon, and this problem demands fairly sophisticated spherical geometry. Finding the direction of Mecca and the time of Salah are the reasons which led to Muslims developing spherical geometry. Solving any of these problems involves finding the unknown sides or angles of a triangle on the celestial sphere from the known sides and angles. A way of finding the time of day, for example, is to construct a triangle whose vertices are the zenith, the north celestial pole, and the sun's position. The observer must know the altitude of the sun and that of the pole; the former can be observed, and the latter is equal to the observer's latitude. The time is then given by the angle at the intersection of the meridian (the arc through the zenith and the pole) and the sun's hour circle (the arc through the sun and the pole).[10][17]

The Zij treatises were astronomical books that tabulated the parameters used for astronomical calculations of the positions of the Sun, Moon, stars, and planets. Their principal contributions to mathematical astronomy reflected improved trigonometrical, computational and observational techniques.[92][93] The Zij books were extensive, and typically included materials on chronology, geographical latitudes and longitudes, star tables, trigonometrical functions, functions in spherical astronomy, the equation of time, planetary motions, computation of eclipses, tables for first visibility of the lunar crescent, astronomical and/or astrological computations, and instructions for astronomical calculations using epicyclic geocentric models.[94] Some zījes go beyond this traditional content to explain or prove the theory or report the observations from which the tables were computed.[95]

In observational astronomy, Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī's Zij al-Sindh (830) contains trigonometric tables for the movements of the sun, the moon and the five planets known at the time.[96] Al-Farghani's A compendium of the science of stars (850) corrected Ptolemy's Almagest and gave revised values for the obliquity of the ecliptic, the precessional movement of the apogees of the sun and the moon, and the circumference of the earth.[97] Muhammad ibn Jābir al-Harrānī al-Battānī (853-929) discovered that the direction of the Sun's eccentric was changing,[98] and studied the times of the new moon, lengths for the solar year and sidereal year, prediction of eclipses, and the phenomenon of parallax.[99] Around the same time, Yahya Ibn Abi Mansour wrote the Al-Zij al-Mumtahan, in which he completely revised the Almagest values.[100] In the 10th century, Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi (Azophi) carried out observations on the stars and described their positions, magnitudes, brightness, and colour and drawings for each constellation in his Book of Fixed Stars (964). Ibn Yunus observed more than 10,000 entries for the sun's position for many years using a large astrolabe with a diameter of nearly 1.4 meters. His observations on eclipses were still used centuries later in Simon Newcomb's investigations on the motion of the moon, while his other observations inspired Laplace's Obliquity of the Ecliptic and Inequalities of Jupiter and Saturn's.[101]

In the late 10th century, Abu-Mahmud al-Khujandi accurately computed the axial tilt to be 23°32'19" (23.53°),[102] which was a significant improvement over the Greek and Indian estimates of 23°51'20" (23.86°) and 24°,[103] and still very close to the modern measurement of 23°26' (23.44°). In 1006, the Egyptian astronomer Ali ibn Ridwan observed SN 1006, the brightest supernova in recorded history, and left a detailed description of the temporary star. He says that the object was two to three times as large as the disc of Venus and about one-quarter the brightness of the Moon, and that the star was low on the southern horizon. In 1031, al-Biruni's Canon Mas’udicus introduced the mathematical technique of analysing the acceleration of the planets, and first states that the motions of the solar apogee and the precession are not identical. Al-Biruni also discovered that the distance between the Earth and the Sun is larger than Ptolemy's estimate, on the basis that Ptolemy disregarded the annual solar eclipses.[104][105]

During the "Maragha Revolution" of the 13th and 14th centuries, Muslim astronomers realized that astronomy should aim to describe the behavior of physical bodies in mathematical language, and should not remain a mathematical hypothesis, which would only save the phenomena. The Maragha astronomers also realized that the Aristotelian view of motion in the universe being only circular or linear was not true, as the Tusi-couple showed that linear motion could also be produced by applying circular motions only.[106] Unlike the ancient Greek and Hellenistic astronomers who were not concerned with the coherence between the mathematical and physical principles of a planetary theory, Islamic astronomers insisted on the need to match the mathematics with the real world surrounding them,[107] which gradually evolved from a reality based on Aristotelian physics to one based on an empirical and mathematical physics after the work of Ibn al-Shatir. The Maragha Revolution was thus characterized by a shift away from the philosophical foundations of Aristotelian cosmology and Ptolemaic astronomy and towards a greater emphasis on the empirical observation and mathematization of astronomy and of nature in general, as exemplified in the works of Ibn al-Shatir, al-Qushji, al-Birjandi and al-Khafri.[108][109][110] In particular, Ibn al-Shatir's geocentric model was mathematically identical to the later heliocentric Copernical model.[111]

Mathematical geography and geodesy

The Muslim scholars, who held to the spherical Earth theory, used it in an impeccably Islamic manner, to calculate the distance and direction from any given point on the earth to Mecca. This determined the Qibla, or Muslim direction of prayer. Muslim mathematicians developed spherical trigonometry which was used in these calculations.[112]

Around 830, Caliph al-Ma'mun commissioned a group of astronomers to measure the distance from Tadmur (Palmyra) to al-Raqqah, in modern Syria. They found the cities to be separated by one degree of latitude and the distance between them to be 66 2/3 miles and thus calculated the Earth's circumference to be 24,000 miles.[113] Another estimate given was 56 2/3 Arabic miles per degree, which corresponds to 111.8 km per degree and a circumference of 40,248 km, very close to the currently modern values of 111.3 km per degree and 40,068 km circumference, respectively.[114]

In mathematical geography, Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī, around 1025, was the first to describe a polar equi-azimuthal equidistant projection of the celestial sphere.[115] He was also regarded as the most skilled when it came to mapping cities and measuring the distances between them, which he did for many cities in the Middle East and western Indian subcontinent. He often combined astronomical readings and mathematical equations, in order to develop methods of pin-pointing locations by recording degrees of latitude and longitude. He also developed similar techniques when it came to measuring the heights of mountains, depths of valleys, and expanse of the horizon, in The Chronology of the Ancient Nations. He also discussed human geography and the planetary habitability of the Earth. He hypothesized that roughly a quarter of the Earth's surface is habitable by humans, and also argued that the shores of Asia and Europe were "separated by a vast sea, too dark and dense to navigate and too risky to try" in reference to the Atlantic Ocean and Pacific Ocean.[116]

Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī is considered the father of geodesy for his important contributions to the field,[117][118] along with his significant contributions to geography and geology. At the age of 17, al-Biruni calculated the latitude of Kath, Khwarazm, using the maximum altitude of the Sun. Al-Biruni also solved a complex geodesic equation in order to accurately compute the Earth's circumference, which were close to modern values of the Earth's circumference.[104][119] His estimate of 6,339.9 km for the Earth radius was only 16.8 km less than the modern value of 6,356.7 km. In contrast to his predecessors who measured the Earth's circumference by sighting the Sun simultaneously from two different locations, al-Biruni developed a new method of using trigonometric calculations based on the angle between a plain and mountain top which yielded more accurate measurements of the Earth's circumference and made it possible for it to be measured by a single person from a single location.[120]

Mathematical physics

Ibn al-Haytham's work on geometric optics, particularly catoptrics, in "Book V" of the Book of Optics (1021) contains the important mathematical problem known as "Alhazen's problem" (Alhazen is the Latinized name of Ibn al-Haytham). It comprises drawing lines from two points in the plane of a circle meeting at a point on the circumference and making equal angles with the normal at that point. This leads to an equation of the fourth degree. This eventually led Ibn al-Haytham to derive the earliest formula for the sum of the fourth powers, and using an early proof by mathematical induction, he developed a method for determining the general formula for the sum of any integral powers, which was fundamental to the development of infinitesimal and integral calculus.[70] Ibn al-Haytham eventually solved "Alhazen's problem" using conic sections and a geometric proof, but Alhazen's problem remained influential in Europe, when later mathematicians such as Christiaan Huygens, James Gregory, Guillaume de l'Hôpital, Isaac Barrow, and many others, attempted to find an algebraic solution to the problem, using various methods, including analytic methods of geometry and derivation by complex numbers.[66] Mathematicians were not able to find an algebraic solution to the problem until the end of the 20th century.[121]

Ibn al-Haytham also produced tables of corresponding angles of incidence and refraction of light passing from one medium to another show how closely he had approached discovering the law of constancy of ratio of sines, later attributed to Snell. He also correctly accounted for twilight being due to atmospheric refraction, estimating the Sun's depression to be 19 degrees below the horizon during the commencement of the phenomenon in the mornings or at its termination in the evenings.[122]

Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī (973-1048), and later al-Khazini (fl. 1115-1130), were the first to apply experimental scientific methods to the statics and dynamics fields of mechanics, particularly for determining specific weights, such as those based on the theory of balances and weighing. Muslim physicists applied the mathematical theories of ratios and infinitesimal techniques, and introduced algebraic and fine calculation techniques into the field of statics.[123]

Abu 'Abd Allah Muhammad ibn Ma'udh, who lived in Al-Andalus during the second half of the 11th century, wrote a work on optics later translated into Latin as Liber de crepisculis, which was mistakenly attributed to Alhazen. This was a "short work containing an estimation of the angle of depression of the sun at the beginning of the morning twilight and at the end of the evening twilight, and an attempt to calculate on the basis of this and other data the height of the atmospheric moisture responsible for the refraction of the sun's rays." Through his experiments, he obtained the accurate value of 18°, which comes close to the modern value.[124]

In 1574, Taqi al-Din estimated that the stars are millions of kilometres away from the Earth and that the speed of light is constant, that if light had come from the eye, it would take too long for light "to travel to the star and come back to the eye. But this is not the case, since we see the star as soon as we open our eyes. Therefore the light must emerge from the object not from the eyes."[125][125]

Other fields

Cryptography

In the 9th century, al-Kindi was a pioneer in cryptanalysis and cryptology. He gave the first known recorded explanation of cryptanalysis in A Manuscript on Deciphering Cryptographic Messages. In particular, he is credited with developing the frequency analysis method whereby variations in the frequency of the occurrence of letters could be analyzed and exploited to break ciphers (i.e. crypanalysis by frequency analysis).[126] This was detailed in a text recently rediscovered in the Ottoman archives in Istanbul, A Manuscript on Deciphering Cryptographic Messages, which also covers methods of cryptanalysis, encipherments, cryptanalysis of certain encipherments, and statistical analysis of letters and letter combinations in Arabic.[127] Al-Kindi also had knowledge of polyalphabetic ciphers centuries before Leon Battista Alberti. Al-Kindi's book also introduced the classification of ciphers, developed Arabic phonetics and syntax, and described the use of several statistical techniques for cryptoanalysis. This book apparently antedates other cryptology references by several centuries, and it also predates writings on probability and statistics by Pascal and Fermat by nearly eight centuries.[128]

Ahmad al-Qalqashandi (1355-1418) wrote the Subh al-a 'sha, a 14-volume encyclopedia which included a section on cryptology. This information was attributed to Taj ad-Din Ali ibn ad-Duraihim ben Muhammad ath-Tha 'alibi al-Mausili who lived from 1312 to 1361, but whose writings on cryptology have been lost. The list of ciphers in this work included both substitution and transposition, and for the first time, a cipher with multiple substitutions for each plaintext letter. Also traced to Ibn al-Duraihim is an exposition on and worked example of cryptanalysis, including the use of tables of letter frequencies and sets of letters which can not occur together in one word.

Mathematical induction

The first known proof by mathematical induction was introduced in the al-Fakhri written by Al-Karaji around 1000 AD, who used it to prove arithmetic sequences such as the binomial theorem, Pascal's triangle, and the sum formula for integral cubes.[129][130] His proof was the first to make use of the two basic components of an inductive proof, "namely the truth of the statement for n = 1 (1 = 13) and the deriving of the truth for n = k from that of n = k - 1."[131]

Shortly afterwards, Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) used the inductive method to prove the sum of fourth powers, and by extension, the sum of any integral powers, which was an important result in integral calculus. He only stated it for particular integers, but his proof for those integers was by induction and generalizable.[132][133]

Ibn Yahyā al-Maghribī al-Samaw'al came closest to a modern proof by mathematical induction in pre-modern times, which he used to extend the proof of the binomial theorem and Pascal's triangle previously given by al-Karaji. Al-Samaw'al's inductive argument was only a short step from the full inductive proof of the general binomial theorem.[134]

See also

- List of Muslim mathematicians

- Latin translations of the 12th century

- Islamic science

- Islamic Golden Age

- Inventions in the Muslim world

Notes

- ↑ O'Connor 1999

- ↑ Hogendijk 1999

- ↑ Bernard Lewis in What Went Wrong? Western Impact and Middle Eastern Response