2003 invasion of Iraq

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

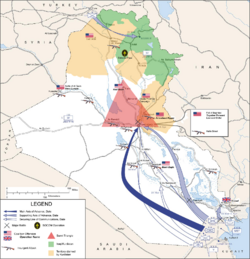

The 2003 invasion of Iraq, from March 20 to May 1, 2003, was spearheaded by the United States, backed by British forces and smaller contingents from Australia, Poland and Denmark. Four countries participated with troops during the initial invasion phase, which lasted from March 20 to May 1. These were the United States (250,000), United Kingdom (45,000), Australia (2,000), and Poland (194). A number of other countries were involved in its aftermath. The invasion marked the beginning of the current Iraq War. In preparation for the invasion, 100,000 U.S. troops were assembled in Kuwait by February 18.[15] The United States supplied the vast majority of the invading forces, but also received support from Kurdish troops in northern Iraq.

According to the President of the United States George W. Bush and former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Tony Blair, the reasons for the invasion were "to disarm Iraq of weapons of mass destruction (WMD), to end Saddam Hussein's support for terrorism, and to free the Iraqi people."[16] According to Blair, he said the trigger was Iraq's failure to take a "final opportunity" to disarm itself of nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons that U.S. and coalition officials called an immediate and intolerable threat to world peace.[17] Although some remnants of pre-1991 production were found after the end of the war, U.S. government spokespeople confirmed that these were not the weapons for which the U.S. went to war.[18][19] In 2005, the Central Intelligence Agency released a report saying that no weapons of mass destruction had been found in Iraq.[20]

In a January 2003 CBS poll 64% of U.S. nationals had approved of military action against Iraq, however 63% wanted President Bush to find a diplomatic solution rather than going to war, and 62% believed the threat of terrorism would increase in the event of war.[21] The invasion of Iraq was strongly opposed by some traditional U.S. allies, including France, Germany and Canada. Their leaders argued that there was no evidence of WMD and that invading Iraq was not justified in the context of UNMOVIC's February 12, 2003 report. On February 15, 2003, a month before the invasion, there were many worldwide protests against the Iraq war, including a rally of 3 million people in Rome, which is listed in the Guinness Book of Records as the largest ever anti-war rally.[22] According to the French academic Dominique Reynié, between January 3 and April 12, 2003, 36 million people across the globe took part in almost 3,000 protests against the Iraq war.[23]

Contents[hide] |

Prelude to the invasion

The Gulf War terminated on April 11, 1991 with a cease-fire negotiated between the U.S. and its allies and Iraq.[24] The U.S. and its allies maintained a policy of “containment” towards Iraq. This policy involved numerous and crushing economic sanctions, U.S. and UK enforcement of Iraqi no-fly zones declared by the U.S. and the U.K. to protect Kurds in northern Iraq and Shias in the south, and ongoing inspections to prevent Iraqi development of chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons. Iraqi military helicopters and planes regularly contested the no-fly zones.[25][26]

Also, the CIA orchestrated a bomb and sabotage campaign between 1992 and 1995 in Iraq via one of the insurgent organizations, the Iraqi National Accord in an unsuccessful attempt to topple the government of Saddam Hussein.[27] The campaign targeted civilian and government targets, including movie theatres and at least one school bus with children on board.[27] The campaign was directed by CIA asset Dr. Iyad Allawi,[28] later installed as interim prime minister of Iraq by the U.S.-led coalition.

In October 1998, regime change became official U.S. policy with enactment of the "Iraq Liberation Act." Enacted following the withdrawal of U.N. weapons inspectors the preceding August, the act provided $97 million for Iraqi "democratic opposition organizations" to "establish a program to support a transition to democracy in Iraq."[29] This legislation contrasted with the terms set out in United Nations Security Council Resolution 687, which focused on weapons and weapons programs and made no mention of regime change.[30] One month after the passage of the “Iraq Liberation Act,” the U.S. and UK launched a bombardment campaign of Iraq called Operation Desert Fox. The campaign’s express rationale was to hamper the Hussein government’s ability to produce chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons, but U.S. national security personnel also hoped it would help weaken Hussein’s grip on power.[31]

With the election of George W. Bush as U.S. President in 2000, the U.S. moved towards a more active policy of “regime change” in Iraq. The Republican Party's campaign platform in the 2000 election called for "full implementation" of the Iraq Liberation Act and removal of Saddam Hussein, and key Bush advisors, including Vice President Dick Cheney, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, and Rumsfeld’s Deputy Paul Wolfowitz, were longstanding advocates of invading Iraq.[32] After leaving the administration, former Bush treasury secretary Paul O'Neill said that an attack on Iraq had been planned since the inauguration, and that the first National Security Council meeting involved discussion of an invasion. O'Neill later backtracked, saying that these discussions were part of a continuation of foreign policy first put into place by the Clinton Administration.[33]

Despite the Bush administration's stated interest in liberating Iraq, little formal movement towards an invasion occurred until the September 11, 2001 attacks. According to aides who were with Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld in the National Military Command Center on September 11, Rumsfeld asked for: "best info fast. Judge whether good enough hit Saddam Hussein at same time. Not only Osama bin Laden." [34] The rationale for invading Iraq as a response to 9/11 has been widely questioned, suggesting there was little cooperation between Iraq and al-Qaeda prior to 9/11.[35]

Shortly after September 11, 2001 (on September 20), President Bush addressed a joint session of Congress (which was simulcasted live to the world), and announced the new War on Terrorism. This announcement was accompanied by the widely criticized doctrine of 'pre-emptive' military action, later termed the Bush doctrine. Some Bush advisers favored an immediate invasion of Iraq, while others advocated building an international coalition and obtaining United Nations authorization. Bush eventually decided to seek U.N. authorization, while still holding out the possibility of invading unilaterally.[36]

President Bush formally makes the case for war

See Public relations preparations for 2003 invasion of Iraq

While there had been some earlier talk of action against Iraq, the Bush administration waited until September 2002 to call for action, with White House Chief of Staff Andrew Card saying, "From a marketing point of view, you don't introduce new products in August."[37] Bush began formally making his case to the international community for an invasion of Iraq in his September 12, 2002 address to the U.N. Security Council.[38] Key U.S. allies in NATO,such as the United Kingdom, agreed with the U.S. actions, while France and Germany were critical of plans to invade Iraq, arguing instead for continued diplomacy and weapons inspections. After considerable debate, the U.N. Security Council adopted a compromise resolution, 1441, which authorized the resumption of weapons inspections and promised "serious consequences" for noncompliance. Security Council members France and Russia made clear that they did not believe these consequences to include the use of force to overthrow the Iraqi government.[39] Both the U.S. ambassador to the UN, John Negroponte, and the UK ambassador Jeremy Greenstock publicly confirmed this reading of the resolution, assuring that Resolution 1441 provided no "automaticity" or "hidden triggers" for an invasion without further consultation of the Security Council.[40]

U.N. Security Council passed Resolution 1441, gave Iraq "a final opportunity to comply with its disarmament obligations" and set up inspections of Iraq by the United Nations Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission (UNMOVIC) and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Saddam Hussein accepted the resolution on November 13 and inspectors returned to Iraq under the direction of UNMOVIC chairman Hans Blix and IAEA Director General Mohamed ElBaradei. As of February 2003, the IAEA "found no evidence or plausible indication of the revival of a nuclear weapons programme in Iraq"; the IAEA concluded that certain items which could have been used in nuclear enrichment centrifuges, such as aluminum tubes, were in fact intended for other uses.[41] UNMOVIC "did not find evidence of the continuation or resumption of programmes of weapons of mass destruction" or significant quantities of proscribed items. UNMOVIC did supervise the destruction of a small number of empty chemical rocket warheads, 50 liters of mustard gas that had been declared by Iraq and sealed by UNSCOM in 1998, and laboratory quantities of a mustard gas precursor, along with about 50 Al-Samoud missiles of a design that Iraq claimed did not exceed the permitted 150 km range, but which had travelled up to 183 km in tests. Shortly before the invasion, UNMOVIC stated that it would take "months" to verify Iraqi compliance with resolution 1441.[42][43][44]

The Bush Administration also sought domestic authorization for an invasion. In October 2002 the U.S. Congress passed a "Joint Resolution to Authorize the Use of United States Armed Forces Against Iraq". While the resolution authorized the President to "use any means necessary" against Iraq, Americans polled in January 2003 widely favored further diplomacy over an invasion. Later that year, however, Americans began to agree with Bush's plan. The U.S. government engaged in an elaborate domestic public relations campaign to market the war to the American people. See, Public relations preparations for 2003 invasion of Iraq. Americans overwhelmingly believed Hussein did have weapons of mass destruction: 85% said so, even though the inspectors had not uncovered those weapons. Of those who thought Iraq had weapons stashed somewhere, about half were pessimistic that they would ever turn up. By February 2003, 74% of Americans supported taking military action to remove Saddam Hussein from power.[21]

In February 2003, U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell addressed the United Nations General Assembly, continuing U.S. efforts to gain U.N. authorization for an invasion. Powell presented evidence alleging that Iraq was actively producing chemical and biological weapons and had ties to al-Qaeda, claims that have since been widely discredited. As a follow-up to Powell’s presentation, the United States, United Kingdom, Poland, Italy, Australia, Denmark, Japan, and Spain proposed a UN Resolution authorizing the use of force in Iraq, but NATO members like Canada, France, and Germany, together with Russia, strongly urged continued diplomacy. Facing a losing vote as well as a likely veto from France and Russia, the U.S., UK, Spain, Poland, Denmark, Italy, Japan, and Australia eventually withdrew their resolution.[45][46]

With the failure of its resolution, the U.S. and their supporters abandoned the Security Council procedures and decided to pursue the invasion without U.N. authorization, a decision of questionable legality under international law.[47] This decision was widely unpopular worldwide, and opposition to the invasion coalesced on February 15 in a worldwide anti-war protest that attracted big between six and ten million people in more than 800 cities, the largest such protest in human history according to the Guinness Book of World Records.[48]

In March 2003, the United States, United Kingdom, Spain, Australia, Poland, Denmark, and Italy began preparing for the invasion of Iraq, with a host of public relations, and military moves. In his March 17, 2003 address to the nation, Bush demanded that Hussein and his two sons Uday and Qusay surrender and leave Iraq, giving them a 48-hour deadline.[49] But Bush actually began the bombing of Iraq on March 18, the day before his deadline expired. On March 18, 2003, the bombing of Iraq by the United States, the United Kingdom, Spain, Italy, Poland, Australia, and Denmark began, without UN support, unlike the first Gulf War or the invasion of Afghanistan.

Back-channel talks

In December 2002, a representative of the head of Iraqi Intelligence, Gen. Tahir Jalil Habbush al-Tikriti, contacted former CIA counterterrorism head Vincent Cannistraro, stating that Saddam "knew there was a campaign to link him to September 11 and prove he had weapons of mass destruction (WMDs)." Cannistrano further added that "the Iraqis were prepared to satisfy these concerns. I reported the conversation to senior levels of the state department and I was told to stand aside and they would handle it." Cannistrano stated that the offers made were all "killed" by the Bush administration because they allowed Saddam Hussein to remain in power - an outcome viewed as unacceptable. It has been suggested that Saddam Hussein was prepared to go into exile if allowed to keep $1 billion USD.[50]

Shortly after, Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak's national security advisor, Osama al Baz, sent a message to the U.S. State Department that the Iraqis wanted to discuss the accusations that Saddam had weapons of mass destruction and ties with al-Qaeda. Iraq also attempted to reach the US through the Syrian, French, German, and Russian intelligence services. Nothing came of the attempts.

In January 2003, Lebanese-American Imad Hage met with Michael Maloof of the DoD's Office of Special Plans. Hage, a resident of Beirut, had been recruited by the department to assist in the War on Terrorism. He reported that Mohammed Nassif, a close aide to Syrian president Bashar al-Assad, had expressed frustrations about the difficulties of Syria contacting the United States, and had attempted to use him as an intermediary. Maloof arranged for Hage to meet with civilian Richard Perle, then head of the Defense Policy Board.

In February 2003, Hage met with the chief of Iraqi intelligence's foreign operations, Hassan al-Obeidi. Obeidi told Hage that Baghdad didn't understand why they were being targeted, and that they had no WMDs; he then made the offer for Washington to send in 2000 FBI agents to ascertain this. He additionally offered oil concessions, but stopped short of having Hussein give up power, instead suggesting that elections could be held in two years. Later, Obeidi suggested that Hage travel to Baghdad for talks; he accepted.

Later that month, Hage met with Gen. Habbush in addition to Iraqi Deputy Prime Minister Tariq Aziz. He was offered top priority to US firms in oil and mining rights, UN-supervised elections, US inspections (with up to 5,000 inspectors), to have al-Qaeda agent Abdul Rahman Yasin (in Iraqi custody since 1994) handed over as a sign of good faith, and to give "full support for any US plan" in the Arab-Israeli peace process. They also wished to meet with high-ranking US officials. On February 19, Hage faxed Maloof his report of the trip. Maloof reports having brought the proposal to Jamie Duran. The Pentagon denies that either Wolfowitz or Rumsfeld, Duran's bosses, were aware of the plan.

On February 21, Maloof informed Duran in an email that Richard Perle wished to meet with Hage and the Iraqis if the Pentagon would clear it. Duran responded "Mike, working this. Keep this close hold." On March 7, Perle met with Hage in Knightsbridge, and stated that he wanted to pursue the matter further with people in Washington (both have acknowledged the meeting). A few days later, he informed Hage that Washington refused to let him meet with Habbush to discuss the offer (Hage stated that Perle's response was "that the consensus in Washington was it was a no-go"). Perle told The Times, "The message was 'Tell them that we will see them in Baghdad."

Casus belli and rationale

George Bush, speaking in October 2002, said that “The stated policy of the United States is regime change… However, if Hussein were to meet all the conditions of the United Nations, the conditions that I have described very clearly in terms that everybody can understand, that in itself will signal the regime has changed”.[51] Based on claims from intelligence sources, George Bush stated on March 6, 2003 that he believed that Saddam Hussein was not complying with UN Resolution 1441, which granted Iraq a final opportunity to disarm itself of Weapons of Mass Destruction, certain missile types, and other components and technologies.[52]

In September 2002, Tony Blair stated, in an answer to a parliamentary question, that “Regime change in Iraq would be a wonderful thing. That is not the purpose of our action; our purpose is to disarm Iraq of weapons of mass destruction…”[53] In November of that year, Tony Blair further stated that “So far as our objective, it is disarmament, not régime change - that is our objective. Now I happen to believe the regime of Saddam is a very brutal and repressive regime, I think it does enormous damage to the Iraqi people... so I have got no doubt Saddam is very bad for Iraq, but on the other hand I have got no doubt either that the purpose of our challenge from the United Nations is disarmament of weapons of mass destruction, it is not regime change.”[54] At a press conference on January 31, 2003, George Bush again reiterated that the single trigger for the invasion would be Iraq’s failure to disarm: “Saddam Hussein must understand that if he does not disarm, for the sake of peace, we, along with others, will go disarm Saddam Hussein.”[55] As late as February 25, 2003, it was still the official line that the only cause of invasion would be a failure to disarm. As Tony Blair made clear in a statement to the House of Commons: “I detest his regime. But even now he can save it by complying with the UN's demand. Even now, we are prepared to go the extra step to achieve disarmament peacefully.”[56]

Additional justifications used at various times included Iraqi violation of UN resolutions, Saddam's repression of Iraqis and Iraqi violations of the 1991 cease-fire[16]

The main allegations were that Saddam Hussein was in possession of, or was attempting to produce, weapons of mass destruction; and that he had ties to terrorists, specifically al-Qaeda. Moreover, it has also been alleged by some commentators that, while it never made an explicit connection between Iraq and the September 11 attacks, the Bush Administration did repeatedly insinuate a link, thereby creating a false impression for the American public. For example, The Washington Post has noted that

While not explicitly declaring Iraqi culpability in the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, administration officials did, at various times, imply a link. In late 2001, Cheney said it was "pretty well confirmed" that attack mastermind Mohamed Atta had met with a senior Iraqi intelligence official. Later, Cheney called Iraq the "geographic base of the terrorists who had us under assault now for many years, but most especially on 9/11."[57]

Steven Kull, director of the Program on International Policy Attitudes (PIPA) at the University of Maryland, observed in March 2003 that "The administration has succeeded in creating a sense that there is some connection [between Sept. 11 and Saddam Hussein]". This was following a New York Times/CBS poll that showed 45% of Americans believing Saddam Hussein was "personally involved" in the September 11 atrocities. As the Christian Science Monitor observed at the time, while "Sources knowledgeable about US intelligence say there is no evidence that Hussein played a role in the Sept. 11 attacks, nor that he has been or is currently aiding Al Qaeda... the White House appears to be encouraging this false impression, as it seeks to maintain American support for a possible war against Iraq and demonstrate seriousness of purpose to Hussein's regime." The CSM went on to report that, while polling data collected "right after Sept. 11, 2001" showed that only 3 percent mentioned Iraq or Saddam Hussein, by January 2003 attitudes "had been transformed" with a Knight Ridder poll showing that 44% of Americans believed "most" or "some" of the September 11 hijackers were Iraqi citizens.[58]

The BBC has also noted that while President Bush "never directly accused the former Iraqi leader of having a hand in the attacks on New York and Washington", he "repeatedly associated the two in keynote addresses delivered since September 11", adding that "Senior members of his administration have similarly conflated the two." For instance, the BBC report quotes Colin Powell in February 2003, stating that "We've learned that Iraq has trained al-Qaeda members in bomb-making and poisons and deadly gases. And we know that after September 11, Saddam Hussein's regime gleefully celebrated the terrorist attacks on America." The same BBC report, from September 2003, also noted the results of a recent opinion poll, which suggested that "70% of Americans believe the Iraqi leader was personally involved in the attacks."[59] Also in September 2003, the Boston Globe reported that "Vice President Dick Cheney, anxious to defend the White House foreign policy amid ongoing violence in Iraq, stunned intelligence analysts and even members of his own administration this week by failing to dismiss a widely discredited claim: that Saddam Hussein might have played a role in the Sept. 11 attacks."[60] A year later, Presidential candidate John Kerry alleged that Cheney was continuing "to intentionally mislead the American public by drawing a link between Saddam Hussein and 9/11 in an attempt to make the invasion of Iraq part of the global war on terror."[61]

Throughout 2002, the Bush administration made clear that removing Saddam Hussein from power in order to restore international peace and security was a major goal. The principal stated justifications for this policy of "regime change" were that Iraq's continuing production of weapons of mass destruction and known ties to terrorist organizations, as well as Iraq's continued violations of UN Security Council resolutions, amounted to a threat to the U.S. and the world community.

The Bush administration's overall rationale for the invasion of Iraq was presented in detail by Secretary of State Colin Powell to the United Nations Security Council on February 5, 2003; in summary, he stated:

| “ |

|

” |

Since the invasion, U.S. and British claims concerning Iraqi weapons programs and links to terrorist organizations have been discredited. While the debate of whether Iraq intended to develop chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons in the future remains open, no WMDs have been found in Iraq since the invasion despite comprehensive inspections lasting more than 18 months.[63] In Cairo, on February 24, 2001, Colin Powell had predicted as much, saying "He [Saddam Hussein] has not developed any significant capability with respect to weapons of mass destruction. He is unable to project conventional power against his neighbours."[64] Similarly, assertions of significant operational links between Iraq and al Qaeda have largely been discredited by the intelligence community, and Secretary Powell himself eventually admitted he had no incontrovertible proof.[65]

In September 2002, the Bush administration said attempts by Iraq to acquire thousands of high-strength aluminium tubes pointed to a clandestine program to make enriched uranium for nuclear bombs. Indeed, Colin Powell, in his address to the U.N. Security Council just prior to the war, made reference to the aluminium tubes. But a report released by the Institute for Science and International Security in 2002 reported that it was highly unlikely that the tubes could be used to enrich uranium. Powell later admitted he had presented an inaccurate case to the United Nations on Iraqi weapons, based on sourcing that was wrong and in some cases "deliberately misleading."[66][67][68]

Habbush letter

Based on the statements of several named CIA senior officials, who deny the allegations, Pulitzer-prize winning journalist Ron Suskind's book "The Way of the World: A Story of Truth and Hope in an Age of Extremism" alleges that the White House ordered the CIA to forge a letter made to appear as a letter from the head of Iraqi intelligence, Tahir Jalil Habbush, to Saddam Hussein and backdated to July 1, 2001. U.S. intelligence officials stated on the record that President Bush was informed unequivocally in January 2003 that Saddam had no weapons of mass destruction. However, eager for "evidence" justifying war against Iraq, the White House ordered the manufacture of a letter stating that 9/11 ringleader Mohammed Atta had trained for his mission in Iraq, thus purporting to establish with finality the existence of an operation link between Saddam and al-Qaeda.[69] The White House also wanted the forged letter to state that Saddam was buying yellowcake from Niger with help from a "small team from the al Qaeda organization."

Suskind also asserts, searching for a justification for invasion, Vice President Cheney's office had been pressuring the CIA to prove that an operation link existed between Saddam and al-Qaeda. Pursuant to the White House order, the CIA concocted the handwritten letter as ordered, with Habbush's name on it, and then hand-carried it agent to Baghdad for dissemination." The forged letter was released and written about by Western newssources as “really concrete proof that al-Qaeda was working with Saddam.”[69]

When interviewed on his sources, Suskind states his sources were "on the record, off the record"[70] and when asked on August 8, 2008 in the Situation Room hosted by Wolf Blitzer about the tapes of his interviews, Suskind replied "I have worked with confidential sources, on the record, off the record, for many, many years, and I have always hesitated, and still hesitate to ever dump tapes."[70].

Critics

The White House denies Suskind's claims as Deputy Press Secretary Tony Fratto states "The notion that the White House directed anyone to forge a letter from Habbush to Saddam Hussein is absurd."[7] Veteran Washington Post White House Watcher Dan Froomkin has characterized this White House response as "a classic non-denial denial." According to Froomkin, Suskind's charges are so "incredibly grave" that they demand a serious response from the government, but all the White House produced was "hyperbole, innuendo and narrowly constructed denials."[71]

Former CIA Director George Tenent also rejects Suskind's accusations of the United States carrying credible intelligence prior to the invasion of Iraq.[72] Two former CIA officers also denies Suskind's claims[72] including prominent CIA former Deputy Director of Clandestine Operations, Robert Richer who is on the record saying “I never received direction from George Tenet (CIA director at the time) or anyone else in my chain of command to fabricate a document as outlined in Mr. Suskind’s book.”[72] Richer has also spoken to John Maguire, who led the CIA’s Iraq Operations Group at the time. Maguire gave Richer permission to state the following on his behalf: "I never received any instruction from then Chief/NE Rob Richer or any other officer in my chain of command instructing me to fabricate such a letter. Further, I have no knowledge to the origins of the letter and as to how it circulated in Iraq.”[72]

These statements by CIA officials were released by the White House and according to some raise many questions about the nature of the denials.[71] Ron Suskind responded that given that the testimony of these few men "could mean the impeachment ostensibly of the president" he would expect the named CIA officials to feel enormous pressure from the government to change or to tone down their statements, but that he had all their interviews on tape. Mr. Suskind has never produced the tapes or any evidence to substantiate his claims.

Yellowcake from Niger

The Bush Administration asserted that the Hussein government had sought to purchase yellowcake uranium from Niger.[73] On March 7, 2003, the U.S. submitted intelligence documents as evidence to the IAEA. These documents were dismissed by the IAEA as forgeries, with the concurrence in that judgment of outside experts. At the time, a U.S. official claimed that the evidence was submitted to the IAEA without knowledge of its provenance, and characterized any mistakes as "more likely due to incompetence not malice"; this explanation was deemed unsatisfactory by former CIA official and Iraq War critic Ray Close.[74] Those who oppose these critics of the invasion maintain the fraudulent documents were never central--or even relevant--in intelligence assessments regarding Iraq seeking uranium. In any case, the charge by the U.S. that Iraq was developing weapons of mass destruction capabilities based on these documents was central to the U.S. public relations campaign to sell the war.

The Downing Street memorandum

The 2005 release of the so-called Downing Street Memo, a secret British document summarizing a 2002 meeting among British political, intelligence, and defence leaders also tended to show the US and Britain willing to "fix" intelligence as necessary to support the war against Iraq. According to the memo, Chief of the British Secret Intelligence Service Sir Richard Dearlove claimed that "Bush wanted to remove Saddam, through military action, justified by the conjunction of terrorism and WMD. But the intelligence and facts were being fixed around the policy."[75]

Creation of Pentagon unit

Between September, 2002 and June, 2003, Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz created a Pentagon unit known as the Office of Special Plans (OSP), headed by Douglas Feith. The unit was created to supply senior Bush administration officials with raw intelligence pertaining to Iraq, unvetted by intelligence analysts, and circumventing traditional intelligence gathering operations by the CIA. One former CIA officer described the OSP as dangerous for U.S. national security and a threat to world peace, and that it lied and manipulated intelligence to further its agenda of removing Saddam Hussein. He described it as a group of ideologues with pre-determined notions of truth and reality, taking bits of intelligence to support their agenda and ignoring anything contrary.[76]. This, however, was disputed by Douglas Feith in his book War and Decision where he notes the unit was created to deal with the sheer volume of work related to Iraq and separate it from other responsibilities.

Non-existent capabilities of unmanned Iraqi drones

In October, 2002, a few days before the U.S. Senate vote on the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution, about 75 senators were told in closed session that Saddam Hussein had the means of delivering biological and chemical weapons of mass destruction by unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) drones that could be launched from ships off the Atlantic coast to attack U.S. eastern seaboard cities. Colin Powell suggested in his presentation to the United Nations that UAVs were transported out of Iraq and could be launched against the U.S. In fact, Iraq had no offensive UAV fleet or any capability of putting UAVs on ships.[77] Iraq's UAV fleet consisted of less than a handful of outdated Czech training drones.[78] At the time, there was a vigorous dispute within the intelligence community as to whether the CIA's conclusions about Iraq's UAV fleet were accurate. The U.S. Air Force agency most familiar with UAVs denied outright that Iraq possessed any offensive UAV capability.[79]

As evidence supporting U.S. and British claims about Iraqi WMDs and links to terrorism weakened, some claim supporters of the invasion have increasingly shifted their justification to the human rights violations of the Hussein government.[80] Leading human rights groups such as Human Rights Watch have argued, however, that they believe human rights concerns were never a central justification for the invasion, nor do they believe that military intervention was justifiable on humanitarian grounds, most significantly because "the killing in Iraq at the time was not of the exceptional nature that would justify such intervention."[81] Many supporters of the war, however, claim from the start human rights concerns were among the reasons given for the invasion, and that the threat of weapons of mass destruction was emphasized at the United Nations, since this dealt with Iraq flouting UN resolutions. They further claim human rights groups that oppose the war have no objective standard regarding when to invade a country.

Notwithstanding the stated justifications for the invasion, critics of the Bush Administration have also argued that the true motives included ensuring U.S. access to Iraqi oil and long term U.S. dominance in the Middle East.[82] Bush Administration officials have vehemently denied these claims.[83] In 2006, the French author Jean-François Susbielle wrote a book entitled Chine-USA, la guerre programmée in which he claimed that the USA invaded Iraq in 2003 in order to control as many major oil fields as possible, thus enabling the US to monitor and determine the extent of China’s access to foreign oil. He believes that various neoconservatives view China as a strategic challenge that must be contained. Many supporters of the war counter that other nations made special deals with Iraq to buy its oil, and that if the US were interested primarily in oil it too could have made a deal. This surely would have been an easier route to fulfilling strategic energy objectives than fighting a war. Furthermore, they claim, oil was more instrumental in creating opposition to the war than support for it, since many nations, especially in Europe, wanted to maintain the oil supply they were receiving from Iraq.

The allegation that the Iraq war was mainly about oil has since been supported by the remarks of Alan Greenspan, the recently retired head of the US Federal Reserve. In media coverage in advance of the publication of his memoirs, Greenspan is reported to have written that,

"I am saddened that it is politically inconvenient to acknowledge what everyone knows: the Iraq war is largely about oil."[84]

The media widely interpreted this as meaning that the casus belli was the appropriation of Iraqi oil. When asked to further elaborate, Greenspan said it was clear to him that Saddam Hussein had wanted to control the Straits of Hormuz and so control Middle East oil shipments through the vital route out of the Gulf. He said that had Saddam been able to do that it would have been "devastating to the West" as the former Iraqi president could have forcibly denied the export of 5m barrels a day and brought "the industrial world to its knees."[85]

Legality of invasion

With an overwhelming majority of Republicans voting to support it and most Democrats voting against it, the United States Congress passed the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 2002. The resolution asserts the authorization by the Constitution of the United States and the Congress for the President to fight anti-United States terrorism. Citing the Iraq Liberation Act of 1998, the resolution reiterated that it should be the policy of the United States to remove the Saddam Hussein regime and promote a democratic replacement. The resolution "supported" and "encouraged" diplomatic efforts by President George W. Bush to "strictly enforce through the U.N. Security Council all relevant Security Council resolutions regarding Iraq" and "obtain prompt and decisive action by the Security Council to ensure that Iraq abandons its strategy of delay, evasion, and noncompliance and promptly and strictly complies with all relevant Security Council resolutions regarding Iraq." The resolution authorized President Bush to use the Armed Forces of the United States "as he determines to be necessary and appropriate" in order to "defend the national security of the United States against the continuing threat posed by Iraq; and enforce all relevant United Nations Security Council Resolutions regarding Iraq."

The legality of the invasion of Iraq has been challenged since its inception on a number of fronts, and several prominent supporters of the invasion in all the invading nations have publicly and privately cast doubt on its legality. It is claimed that the invasion was fully legal because authorization was implied by the United Nations Security Council.[86][87] International legal experts, including the International Commission of Jurists, a group of 31 leading Canadian law professors, and the U.S.-based Lawyers Committee on Nuclear Policy have denounced both of these rationales.[88][89][90]

On Thursday November 20, 2003, an article published in the Guardian alleged that Richard Perle, a senior member of the administration's Defense Policy Board Advisory Committee, conceded that the invasion was illegal but still justified.[91][92]

The United Nations Security Council has passed nearly 60 resolutions on Iraq and Kuwait since Iraq's invasion of Kuwait in 1990. The most relevant to this issue is Resolution 678, passed on November 29, 1990. It authorizes "member states co-operating with the Government of Kuwait... to use all necessary means" to (1) implement Security Council Resolution 660 and other resolutions calling for the end of Iraq's occupation of Kuwait and withdrawal of Iraqi forces from Kuwaiti territory and (2) "restore international peace and security in the area." Resolution 678 has not been rescinded or nullified by succeeding resolutions and Iraq was not alleged after 1991 to invade Kuwait or to threaten do so.

Resolution 1441 was most prominent during the run up to the war and formed the main backdrop for Secretary of State Colin Powell's address to the Security Council one month before the invasion.[93] At the same time, Bush Administration officials advanced a parallel legal argument using the earlier resolutions, which authorized force in response to Iraq's 1991 invasion of Kuwait. Under this reasoning, by failing to disarm and submit to weapons inspections, Iraq was in violation of U.N. Security Council Resolutions 660 and 678, and the U.S. could legally compel Iraq's compliance through military means.

Critics and proponents of the legal rationale based on the U.N. resolutions argue that the legal right to determine how to enforce its resolutions lies with the Security Council alone, not with individual nations.

In February 2006, Luis Moreno-Ocampo, the lead prosecutor for the International Criminal Court, reported that he had received 240 separate communications regarding the legality of the war, many of which concerned British participation in the invasion.[94] In a letter addressed to the complainants, Mr. Moreno-Ocampo explained that he could only consider issues related to conduct during the war and not to its underlying legality as a possible crime of aggression because no provision had yet been adopted which "defines the crime and sets out the conditions under which the Court may exercise jurisdiction with respect to it." In a March 2007 interview with the Sunday Telegraph, Moreno-Ocampo encouraged Iraq to sign up with the court so that it could bring cases related to alleged war crimes.[95] Luis Moreno-Ocampo also stated that his extensive investigation found no evidence for any war crime or any crime against humanity.

United States Ohio Congressman Dennis Kucinich held a press conference on the evening of April 24, 2007, revealing US House Resolution 333 and the three articles of impeachment against Vice President Dick Cheney. He charges Cheney with manipulating the evidence of Iraq's weapons program, deceiving the nation about Iraq's connection to al-Qaeda, and threatening aggression against Iran in violation of the United Nations Charter.

- See also: Legitimacy of the 2003 invasion of Iraq, Failed Iraqi peace initiatives, Views on the 2003 invasion of Iraq, and Opposition to the 2003 Iraq War

Military aspects

United States military operations were conducted under the codename Operation Iraqi Liberation.[96] The codename was later changed to Operation Iraqi Freedom The United Kingdom military operation was named Operation Telic.

Multilateral support

In November 2002, U.S. President George W. Bush, visiting Europe for a NATO summit, declared that "should Iraqi President Saddam Hussein choose not to disarm, the United States will lead a coalition of the willing to disarm him."[97]

Thereafter, the Bush administration briefly used the term Coalition of the Willing to refer to the countries who supported, militarily or verbally, the military action in Iraq and subsequent military presence in post-invasion Iraq since 2003. The original list prepared in March 2003 included 49 members.[98] Of those 49, only seven besides the U.S. contributed troops to the invasion force (the United Kingdom, Spain, Italy, Australia, Poland, Portugal and Denmark), 33 provided some number of troops to support the occupation after the invasion was complete. Six members have no military.

Invasion force

Approximately 248,000 Soldiers and Marines from the United States, 45,000 British soldiers, 2,000 Australian soldiers, 1,300 Spanish soldiers, 500 Danish soldiers and 194 Polish soldiers were sent to Kuwait for the invasion.[99] The invasion force was also supported by Iraqi Kurdish militia troops, estimated to number upwards of 70,000.[8] In the latter stages of the invasion 620 troops of the Iraqi National Congress opposition group were deployed to southern Iraq.[4]

A U.S. Central Command, Combined Forces Air Component Commander report, indicated that as of April 30, 2003, there were a total of 466,985 U.S. personnel deployed for Operation Iraqi Freedom. This included USAF, 54,955; USAF Reserve, 2,084; USAF National Guard, 7,207; USMC, 74,405; USMC Reserve, 9,501; USN, 61,296 (681 are members of the U.S. Coast Guard); USN Reserve, 2,056; and USA, 233,342; USA Reserve, 10,683; and USA National Guard, 8,866.[100]

Plans for opening a second front in the north were severely hampered when Turkey refused the use of its territory for such purposes.[101] In response to Turkey's decision, the United States dropped several thousand paratroopers from the 173rd Airborne Brigade into northern Iraq, a number significantly less than the 15,000 strong 4th Mechanized Infantry Division that the U.S. originally planned to use for opening the northern front.[102]

Defending force

The number of personnel in the Iraqi military prior to the war was uncertain, but it was believed to have been poorly equipped.[103][104][105] The International Institute for Strategic Studies estimated the Iraqi armed forces to number 538,000 (army 375,000, navy 2,000, air force 20,000 and air defense 17,000), the paramilitary Fedayeen Saddam 44,000,republican guard 80,000 and reserves 650,000.[106] Another estimate numbers the army and Republican Guard at between 280,000 to 350,000 and 50,000 to 80,000, respectively,[107] and the paramilitary between 20,000 and 40,000.[108] There were an estimated thirteen infantry divisions, ten mechanized and armored divisions, as well as some special forces units. The Iraqi Air Force and Iraqi Navy played a negligible role in the conflict.

In addition to Iraqi forces, during the invasion foreign volunteers from Syria traveled to Iraq and took part in the fighting, usually under the command of the Saddam Fedayeen. It is not known for certain how many foreign fighters fought in Iraq in 2003, however, intelligence officers of the U.S. First Marine Division estimated that 50% of all Iraqi combatants in central Iraq were foreigners.[5][6]

In addition, the terrorist group Ansar al-Islam controlled a small section of northern Iraq in an area outside of Saddam Hussein's control. Ansar al-Islam had been fighting against Kurdish forces since 2001. At the time of the invasion they fielded an estimated 600 to 800 fighters.[109] Ansar al-Islam was led by the Jordanian-born militant Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, who would later become an important leader in the Iraqi insurgency. Ansar al-Islam was driven out of Iraq in late March by a joint American-Kurdish force during Operation Viking Hammer.

Invasion

| UK bomb tonnage (2002) [110] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mar | 0.0 | |||

| Apr | 0.3 | |||

| May | 7.3 | |||

| Jun | 10.4 | |||

| Jul | 9.5 | |||

| Aug | 14.1 | |||

| Sep | 54.6 | |||

| Oct | 17.7 | |||

| Nov | 33.6 | |||

| Dec | 53.2 | |||

Since the 1991 Persian Gulf War, the U.S. and UK had been engaged in a low-level attacks on Iraqi air defenses which targeted them while enforcing Iraqi no-fly zones.[25][26] These zones, and the attacks to enforce them, were described as illegal by the former UN Secretary General, Boutros Boutros-Ghali and the then French foreign minister, Hubert Vedrine. Other countries, notably Russia and China, also condemned the zones as a violation of Iraqi sovereignty.[111][112][113] In mid-2002, the U.S. began more carefully selecting targets in the southern part of the country to disrupt the military command structure in Iraq and "pressure" the Iraqi Government into providing a pretext for war. A change in enforcement tactics was acknowledged at the time, but it was not made public that this was part of a plan known as Operation Southern Focus.

The amount of ordnance dropped on Iraqi positions by Coalition aircraft in 2001 and 2002 was less than in 1999 and 2000 which was during the Clinton administration.[114] This information has been used to attempt to refute the theory that the Bush administration had already decided to go to war against Iraq before coming to office and that the bombing during 2001 and 2002 was laying the ground work for the eventual invasion in 2003. However, information obtained by the UK Liberal Democrats showed that the UK dropped twice as many bombs on Iraq in the second half of 2002 as they did during the whole of 2001. The tonnage of UK bombs dropped increased from 0 in March 2002 and 0.3 in April 2002 to between 7 and 14 tons per month in May-August, reaching a pre-war peak of 54.6 tons in September - prior to Congress' October 11 authorization of the invasion. The September 5 attacks included a 100+ aircraft attack on the main air defense site in western Iraq. According to an editorial in New Statesman this was "Located at the furthest extreme of the southern no-fly zone, far away from the areas that needed to be patrolled to prevent attacks on the Shias, it was destroyed not because it was a threat to the patrols, but to allow allied special forces operating from Jordan to enter Iraq undetected."[110] Tommy Franks, who commanded the invasion of Iraq, has since admitted that the bombing was designed to “degrade” Iraqi air defences in the same way as the air attacks that began the 1991 Gulf war. These "spikes of activity" were, in the words of then British Defence Secretary, Geoff Hoon, designed to 'put pressure on the Iraqi regime' or, as The Times reported, to "provoke Saddam Hussein into giving the allies an excuse for war". In this respect, as provocations designed to start a war, leaked British Foreign Office legal advice concluded that such attacks were illegal under international law.[115][116]

Another attempt at provoking the war was mentioned in a leaked memo from a meeting between George W. Bush and Tony Blair on January 31, 2003 at which Bush allegedly told Blair that "The US was thinking of flying U2 reconnaissance aircraft with fighter cover over Iraq, painted in UN colours. If Saddam fired on them, he would be in breach."[117]

Opening salvo: the Dora Farms strike

The early morning of March 19, 2003, U.S. forces abandoned the plan for initial, non-nuclear decapitation strikes against fifty-five top Iraqi officials, in light of reports that Saddam Hussein was visiting his daughters and sons, Uday and Qusay at Dora Farms, within the al-Dora farming community on the outskirts of Baghdad.[118] At approximately 05:30 UTC two F-117 Nighthawks from the 8th Expeditionary Fighter Squadron[119] dropped four enhanced, satellite-guided 2,000-pound Bunker Busters GBU-27 on the compound. Complementing the aerial bombardment were 40 Tomahawk cruise missiles fired from at least four ships, including Spruance class destroyer, the USS Donald Cook, and two submarines in the Red Sea and Persian Gulf.[120] One missed the compound entirely and the other three missed their target landing on the other side of the wall of the palace compound.[121] Saddam Hussein was not present nor were any members of the Iraqi leadership or Hussein family.[118] The attack killed one civilian and injured fourteen others, including nine women and one child.[122][123] Later investigation revealed that Saddam Hussein had not visited the farm since 1995.[120]

Opening attack

On March 20, 2003 at approximately 02:30 UTC or about 90 minutes after the lapse of the 48-hour deadline, at 05:33 local time, explosions were heard in Baghdad. There is now evidence that various special forces troops (including British SAS, the Australian SASR and 4RAR, the U.S. Army's Delta Force, United States Navy SEALs, United States Army's Green Berets and U.S. Air Force Combat Controllers) crossed the border into Iraq well before the air war commenced to guide strike aircraft in air attacks. At 03:15 UTC, or 10:15 p.m. EST, George W. Bush announced that he had ordered an "attack of opportunity" against targets in Iraq. As soon as this word was given the troops on standby crossed the border into Iraq.

Before the invasion, many observers had expected a lengthy campaign of aerial bombing in advance of any ground action, taking as examples the 1991 Persian Gulf War or the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan. In practice, U.S. plans envisioned simultaneous air and ground assaults to decapitate the Iraqi forces as fast as possible (see Shock and Awe), attempting to bypass Iraqi military units and cities in most cases. The assumption was that superior mobility and co-ordination of Coalition forces would allow them to attack the heart of the Iraqi command structure and destroy it in a short time, and that this would minimize civilian deaths and damage to infrastructure. It was expected that the elimination of the leadership would lead to the collapse of the Iraqi Forces and the government, and that much of the population would support the invaders once the government had been weakened. Occupation of cities and attacks on peripheral military units were viewed as undesirable distractions.

Following Turkey's decision to deny any official use of its territory, the Coalition was forced to abandon a planned simultaneous attack from north and south, so the primary bases for the invasion were in Kuwait and other Persian Gulf nations. One result of this was that one of the divisions intended for the invasion was forced to relocate and was unable to take part in the invasion until well into the war. Many observers felt that the Coalition devoted sufficient numbers of troops to the invasion, but too many were withdrawn after it ended, and that the failure to occupy cities put them at a major disadvantage in achieving security and order throughout the country when local support failed to meet expectations.

The invasion was swift, leading to the collapse of the Iraq government and the military of Iraq in about three weeks. The oil infrastructure of Iraq was rapidly seized and secured with limited damage in that time. Securing the oil infrastructure was considered of great importance to funding the rebuilding of Iraq after the invasion ended. In the Persian Gulf War, while retreating from Kuwait, the Iraqi army had set many oil wells on fire, in an attempt to disguise troop movements and to distract Coalition forces. Prior to the 2003 invasion, Iraqi forces had mined some 400 oil wells around Basra and the Al-Faw peninsula with explosives. Coalition troops launched an air and amphibious assault on the Al-Faw peninsula during the closing hours of March 20 to secure the oil fields there; the amphibious assault was supported by warships of the Royal Navy, Polish Navy, and Royal Australian Navy. The United States Marine Corps' 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit, attached to 3 Commando Brigade and the Polish Special Forces unit GROM attacked the port of Umm Qasr.there they encountered heavy resistance by Iraqi troops. The British Army's 16 Air Assault Brigade also secured the oilfields in southern Iraq in places like Rumaila while the Polish commandos captured offshore oil platforms near the port, preventing their destruction. Despite the rapid advance of the invasion forces, some 44 oil wells were destroyed and set ablaze by Iraqi explosives or by incidental fire. However, the wells were quickly capped and the fires put out, preventing the ecological damage and loss of oil production capacity that had occurred at the end of the Persian Gulf War.

In keeping with the rapid advance plan, the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division moved westward and then northward through the western desert toward Baghdad, while the 1st Marine Expeditionary Force moved along Highway 1 through the center of the country, and 1 (UK) Armoured Division moved northward through the eastern marshland. Spanish units moved south to the Saudi-Iraqi border, then drove north to join U.S. forces. Polish troops moved with U.S. Marines, and Danish soldiers fought with the British and Australians in southern Iraq.

Battle of Nasiriyah

Initially, the U.S. 1st Marine Division fought through the Rumaila oil fields, and moved north to Nasariyah--a moderate-sized, Shi'ite dominated city with important strategic significance as a major road junction and its proximity to nearby Talil Airfield. The United States Army 3rd Infantry Division defeated Iraqi forces entrenched in and around the airfield and bypassed the city to the west. On March 23, U.S Marines pressed the attack in and around Nasiriyah despite facing heavy resistance. American Marines suffered several fatalities during a firefight with Fedayeen as part of the Urban warfare in Nasiriyah. Casualties were generally low throughout most of the battle. During the battle an Air Force A-10 was involved in a case of friendly fire that resulted in the death of six Marines when it accidentally attacked an American amphibious vehicle. Two other vehicles were destroyed when a barrage of RPG and small arms fire killed most of the marines inside.[124] Because of Nasiriyah's strategic position as a road junction, a significant gridlock occurred as U.S. forces moving north converged on the city's surrounding highways. With the Nasiriyah and Tallil Airfields secured, Coalition forces gained an important logistical center in southern Iraq and established FOB/EAF Jalibah, some 10 miles (16 km) outside of Nasiriyah. Additional troops and supplies were soon brought through this forward operating base and Italian and Spanish soldiers were now arriving to advance south of the U.S. Army's advance. The 101st Airborne Division continued its attack north in support of the 3rd Infantry Division. Spanish, British, and Australian paratroopers moved to Tallil. By 27-March 28, a severe sand storm slowed the Coalition advance as the 3rd Infantry Division halted its northward drive half way between Najaf and Karbala. As a result of heavy rains that occurred along with the sand storm, orange-colored mud fell on some parts of the invasion force in the area. Air operations by helicopters, poised to bring reinforcements from the 101st Airborne, were blocked for three days. There was particularly heavy fighting in and around the bridge adjacent to the town of Kufl. During the battle, a convoy included the female American soldiers Jessica Lynch, and Lori Piestewa; the latter was believed to have been the first Native American woman killed in combat in a foreign war. Piestewa was from Tuba City, Arizona and an enrolled member of the Hopi Tribe. Their convoy was ambushed as a result, 11 American soldiers were killed and Lynch was captured. Despite these events, Nasiriyah eventually fell to Coalition forces.

Basra

The Iraqi port city of Umm Qasr was the first British obstacle. A joint Polish-British-American force ran into unexpectadly stiff resistance, and it took several days to clear the Iraqi forces out. Fighting in Umm Qasr cost 14 coalition lives and about 30 Iraqi lives. Farther south, the British units fought their way into Iraq's second-largest city, Basra, on April 6, coming under constant attack by regulars and Fedayeen, while the British Red Devils cleared the 'old quarter' of the city that was inaccessible to vehicles. Entering Basra was achieved after two weeks of fierce fighting. Elements of 1 (UK) Armoured Division began to advance north towards U.S. positions around Al Amarah on April 9. Pre-existing electrical and water shortages continued throughout the conflict and looting began as Iraqi forces collapsed. While Coalition forces began working with local Iraqi Police to enforce order, Royal Electrical Mechanical Engineers (REME) and Royal Engineers of the British Army rapidly set up and repaired dockyard facilities to allow humanitarian aid began to arrive from ships arriving in the port city of Umm Qasr.

After a rapid initial advance, the first major pause occurred in the vicinity of Karbala. There, U.S. Army elements met resistance from Iraqi troops defending cities and key bridges along the Euphrates River. These forces threatened to interdict supply routes as American forces moved north. Eventually, troops from the 101st Abn secured the cities of Najaf and Karbala to prevent any Iraqi counterattacks on the 3rd I.D. lines of communication as the division pressed its advance toward Baghdad.

Special operations

The 2nd Battalion of the U.S. 5th Special Forces Group, United States Army Special Forces (Green Berets) conducted reconnaissance in the cities of Basra, Karbala and various other locations.

In the North, the 10th Special Forces Group (10th SFG) which included U.S., Spanish, British, and Polish paratroopers had the mission of aiding the Kurdish parties, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan and the Kurdistan Democratic Party, de facto rulers of Iraqi Kurdistan since 1991, and employing them against the 13 Iraqi Divisions located in the vicinity of Kirkuk and Mosul. Turkey had officially forbidden any Coalition troops from using their bases or airspace, so lead elements of the 10th SFG had to make a detour infiltration; their flight was supposed to take four hours but instead took ten. Hours after the first of such flights, Turkey did allow the use of its air space and the rest of the 10th SFG infiltrated in. The preliminary mission was to destroy the base of the Kurdish terrorist group Ansar al-Islam, believed to be linked to Al Qaeda. Concurrent and follow-on missions involved attacking and fixing Iraqi forces in the north, thus preventing their deployment to the southern front and the main effort of the invasion.

On March 26, 2003, the 173rd Airborne Brigade augmented the invasion's northern front by parachuting into northern Iraq onto Bashur Airfield, controlled at the time by elements of 10th SFG and Kurdish peshmerga. The fall of Kirkuk on April 10, 2003 to the 10th SFG and Kurdish peshmerga precipitated the 173rd's planned assault, preventing the unit's involvement in combat against Iraqi forces during the invasion. The successful occupation of Kirkuk came as a result of approximately two weeks of fighting that included the Battle of the Green Line (the unofficial border of the Kurdish autonomous zone) and the subsequent Battle of Kani Domlan Ridge (the ridgeline running northwest to southeast of Kirkuk), the latter fought exclusively by 3rd Battalion, 10th SFG and Kurdish peshmerga against the Iraqi I Corps. The 173rd Brigade would eventually take responsibility for Kirkuk days later, becoming involved in the counterinsurgency fight and remain there until redeploying a year later.

Further reinforcing operations in Northern Iraq, the 26th Marine Expeditionary Unit (Special Operations Capable), serving as Landing Force Sixth Fleet, deployed in April to Erbil and subsequently Mosul via Marine KC-130 flights. The 26 MEU(SOC) maintained security of the Mosul airfield and surrounding area until relief by the 101st Airborne Division.

After Sargat was taken, Bravo Company, 3rd Battalion, 10th SFG along with their Kurdish allies pushed south towards Tikrit and the surrounding towns of Northern Iraq. Previously, during the Battle of the Green Line, Bravo Company, 3/10 with their Kurdish allies pushed back, destroyed, or routed the 13th Iraqi Infantry Division. The same company took Tikrit. Iraq was the largest deployment of Special Forces since Vietnam.

Fall of Baghdad (April 2003)

Three weeks into the invasion, US-led Coalition forces moved into Baghdad. Initial plans were for Coalition units to surround the city and gradually move in, forcing Iraqi armor and ground units to cluster into a central pocket in the city, and then attack with air and artillery forces. This plan soon became unnecessary, as an initial engagement of armored units south of the city saw most of the Republican Guard's assets destroyed and routes in the southern outskirts of the city occupied. On April 5 Task Force 1-64 Armor of the U.S. Army's Third Infantry Division executed a raid, later called the "Thunder Run", to test remaining Iraqi defenses, with 29 tanks and 14 Bradley Armored Fighting Vehicles advancing to the Baghdad airport. They met heavy resistance, but were successful in reaching the airport. US troops faced heavy fighting in the airport, and were even temporarily pushed out, but eventually secured the airport. The next day, another brigade of the 3rd I.D. attacked into downtown Baghdad and occupied one of the palaces of Saddam Hussein in fierce fighting. US Marines also faced heavy shelling from Iraqi artillery as they attempted to cross a river bridge. The Iraqi commander directed the fire, and one shell from an Iraqi gun killed or wounded 4 Marines, but the river crossing was successful. The Iraqis managed to inflict heavy casualties on the American forces near the airport from defensive positions but suffered severe casualties from air bombardment. Despite these losses, Iraqi casualties were also high. One American sniper remembered seeing an Iraqi RPG team on a roof out of range. He called in an attack helicopter, which eliminated the entire crew.[125] Within hours of the palace seizure and with television coverage of this spreading through Iraq, U.S. forces ordered Iraqi forces within Baghdad to surrender, or the city would face a full-scale assault. Iraqi government officials had either disappeared or had conceded defeat, and on April 9, 2003, Baghdad was formally occupied by Coalition forces and the power of Saddam Hussein was declared ended. Much of Baghdad remained unsecured however, and fighting continued within the city and its outskirts well into the period of occupation. Saddam had vanished, and his whereabouts were unknown. Many Iraqis celebrated the downfall of Saddam by vandalizing the many portraits and statues of him together with other pieces of his cult of personality.

One widely publicized event was the dramatic toppling of a large statue of Saddam in Baghdad's Fardus Square. This attracted considerable media coverage at the time. As the British Daily Mirror reported,

"For an oppressed people this final act in the fading daylight, the wrenching down of this ghastly symbol of the regime, is their Berlin Wall moment. Big Moustache has had his day."[126]

As Staff Sergeant Brian Plesich reported in On Point: The United States Army in Operation Iraqi Freedom,

"The Marine Corps colonel in the area saw the Saddam statue as a target of opportunity and decided that the statue must come down. Since we were right there, we chimed in with some loudspeaker support to let the Iraqis know what it was we were attempting to do..." "Somehow along the way, somebody had gotten the idea to put a bunch of Iraqi kids onto the wrecker that was to pull the statue down. While the wrecker was pulling the statue down, there were Iraqi children crawling all over it. Finally they brought the statue down"[127]

The fall of Baghdad saw the outbreak of regional, sectarian violence throughout the country, as Iraqi tribes and cities began to fight each other over old grudges. The Iraqi cities of Al-Kut and Nasiriyah launched attacks on each other immediately following the fall of Baghdad to establish dominance in the new country, and the US-led Coalition quickly found themselves embroiled in a potential civil war. US-led Coalition forces ordered the cities to cease hostilities immediately, explaining that Baghdad would remain the capital of the new Iraqi government. Nasiriyah responded favorably and quickly backed down; however, Al-Kut placed snipers on the main roadways into town, with orders that invading forces were not to enter the city. After several minor skirmishes, the snipers were removed, but tensions and violence between regional, city, tribal, and familial groups continued.

General Tommy Franks assumed control of Iraq as the supreme commander of occupation forces. Shortly after the sudden collapse of the defense of Baghdad, rumors were circulating in Iraq and elsewhere that there had been a deal struck (a "safqua") wherein the US-led Coalition had bribed key members of the Iraqi military elite and/or the Ba'ath party itself to stand down. In May 2003, General Franks retired, and confirmed in an interview with Defense Week that the US-led Coalition had paid Iraqi military leaders to defect. The extent of the defections and their effect on the war are unclear.

US-led Coalition troops promptly began searching for the key members of Saddam Hussein's government. These individuals were identified by a variety of means, most famously through sets of most-wanted Iraqi playing cards.

On July 22, 2003 during a raid by the U.S. 101st Airborne Division and men from Task Force 20, Saddam Hussein's sons Uday and Qusay, and one of his grandsons were killed in a massive fire-fight.

Saddam Hussein was captured on December 13, 2003 by the U.S. Army's 4th Infantry Division and members of Task Force 121 during Operation Red Dawn.

Other areas

In the north, Kurdish forces opposed to Saddam Hussein had already occupied for years an autonomous area in northern Iraq. With the assistance of U.S. Special Forces and air strikes, they were able to rout the Iraqi units near them and to occupy oil-rich Kirkuk on April 10.

U.S. special forces had also been involved in the extreme south of Iraq, attempting to occupy key roads to Syria and airbases. In one case two armored platoons were used to convince Iraqi leadership that an entire armored battalion was entrenched in the west of Iraq.

On April 15, U.S. forces took control of Tikrit, the last major outpost in central Iraq, with an attack led by the Marines' Task Force Tripoli. About a week later the Marines were relieved in place by the Army's 4th Infantry Division.

Summary of the invasion

The US-led Coalition forces toppled the government and captured the key cities of a large nation in only 21 days. The invasion did require a large army build-up like the 1991 Gulf War, but many didn't see combat and many were withdrawn after the invasion ended. This proved to be short-sighted, however, due to the requirement for a much larger force to combat the irregular Iraqi forces in the aftermath of the war. General Eric Shinseki, Army Chief of Staff, recommended "several hundred thousand"[128] troops be used to maintain post-war order, but then Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld — and especially his deputy, civilian Paul Wolfowitz — strongly disagreed. General Abizaid later said General Shinseki had been right.

The Iraqi army, armed mainly with Soviet-built equipment, was overall ill-equipped in comparison to the U.S. and UK forces. Attacks on U.S. supply routes by Fedayeen militiamen were repulsed. The Iraqis' artillery proved largely ineffective, and they were unable to mobilize their air force to attempt a defense. The Iraqi T-72 tanks, the heaviest armored vehicles in the Iraqi Army, were both outdated and ill-maintained, and when they were mobilized they were rapidly destroyed, thanks in part to U.S. and UK air supremacy. The U.S. Air Force, Marine Corps, Naval Aviation, and British Royal Air Force operated with impunity throughout the country, pinpointing heavily defended resistance targets and destroying them before ground troops arrived.

The main battle tanks (MBT) of the U.S. and UK forces, the U.S. M1 Abrams and British Challenger 2, proved worthy in the rapid advance across the country. With the large number of rocket propelled grenade (RPG) attacks by irregular Iraqi forces, few U.S. and UK tanks were lost and no tank crewmen were killed by hostile fire. The only tank loss sustained by the British Army was a Challenger 2 of the Queen's Royal Lancers that was hit by another Challenger 2, killing two crewmen. All three British tank crew fatalities were a result of friendly fire.

The Iraqi Army suffered from poor morale, even amongst the elite Republican Guard. Entire units disbanded into the crowds upon the approach of invading troops, or actually sought out U.S. and UK forces out to surrender. In one case, a force of roughly 20-30 Iraqis attempted to surrender to a two-man vehicle repair and recovery team, invoking similar instances of Iraqis surrendering to news crews during the Persian Gulf War. Other Iraqi Army officers were bribed by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) or coerced into surrendering. Worse, the Iraqi Army had incompetent leadership - reports state that Qusay Hussein, charged with the defense of Baghdad, dramatically shifted the positions of the two main divisions protecting Baghdad several times in the days before the arrival of U.S. forces, and as a result the units within were both confused and further demoralized when U.S. Marine and British forces attacked. By no means did the invasion force see the entire Iraqi military thrown against it; U.S. and UK units had orders to move to and seize objective target-points rather than seek engagements with Iraqi units. This resulted in most regular Iraqi military units emerging from the war fully intact and without ever having been engaged by U.S. forces, especially in southern Iraq. It is assumed that most units disintegrated to either join the growing Iraqi insurgency or returned to their homes.

According to the declassified Pentagon report, "The largest contributing factor to the complete defeat of Iraq's military forces was the continued interference by Saddam." The report, designed to help U.S. officials understand in hindsight how Saddam and his military commanders prepared for and fought the invasion, paints a picture of an Iraqi government blind to the threat it faced, hampered by Saddam's inept military leadership and deceived by its own propaganda and inability to believe the United States would invade a sovereign country without provocation. According to the BBC, the report portrays Saddam Hussein as "chronically out of touch with reality - preoccupied with the prevention of domestic unrest and with the threat posed by Iran."[129]

Security, looting and war damage

Looting took place in the days following the 2003 invasion. Similar looting occurred for two weeks following the 1989 U.S. invasion of Panama.

It was reported that the National Museum of Iraq was among the looted sites. Most initial news reports were that 100 percent of the museum's artifacts had been removed by looters. In fact, no more than 3 percent of its contents were removed by thieves.

An assertion that U.S. forces did not guard the museum because they were guarding the Ministry of Oil and Ministry of Interior is disputed by investigator Col. Matthew Bogdanos in his 2005 book, "Thieves of Baghdad." Bogdanos notes that the Ministry of Oil building was bombed, but the museum complex, which took some fire, was not bombed. He also writes that Saddam's troops set up sniper's nests inside and on top of the museum, and nevertheless U.S. Marines and soldiers stayed close enough to prevent wholesale looting.

Early on, U.S. officials reacted defensively to the first, false news reports of 100 percent looting. According to U.S. officials, the "reality of the situation on the ground" was that hospitals, water plants, and ministries with vital intelligence needed security more than other sites. There were only enough U.S. troops on the ground to guard a certain number of the many sites that ideally needed protection, and so, apparently, some "hard choices" were made.

The FBI was soon called into Iraq to track down the stolen items. It was found that the initial claims of looting of substantial portions of the collection were heavily exaggerated. Initial reports claimed a near-total looting of the museum, estimated at upwards of 170,000 inventory lots, or about 501,000 pieces. The most recent estimate places the number of stolen pieces at around 15,000, and about 10,000 of them probably were taken in an "inside job" before U.S. troops arrived, according to Bogdanos. Over 5,000 looted items have since been recovered.[130]

There has been speculation that some objects still missing were not taken by looters during the invasion, but were taken by Saddam Hussein or his entourage before or during the fighting. There have also been reports that early looters had keys to vaults that held rarer pieces, and some have speculated as to the pre-meditated systematic removal of key artifacts.

The National Museum of Iraq was only one of many museums and sites of cultural significance that were affected by the war. Many in the arts and antiquities communities briefed policy makers in advance of the need to secure Iraqi museums. Despite the looting being lighter than initially feared, the cultural loss of items from ancient Sumer is significant.

More serious for the post-war state of Iraq was the looting of cached weaponry and ordnance which fueled the subsequent insurgency. As many as 250,000 tons of explosives were unaccounted for by October 2004.[131] Disputes within the US Defense Department led to delays in the post-invasion assessment and protection of Iraqi nuclear facilities. Tuwaitha, the Iraqi site most scrutinized by UN inspectors since 1991, was left unguarded and may have been looted.[132]

Zainab Bahrani, professor of Ancient Near Eastern Art History and Archaeology at Columbia University, reported that a helicopter landing pad was constructed in the heart of the ancient city of Babylon, and "removed layers of archeological earth from the site. The daily flights of the helicopters rattle the ancient walls and the winds created by their rotors blast sand against the fragile bricks. When my colleague at the site, Maryam Moussa, and I asked military personnel in charge that the helipad be shut down, the response was that it had to remain open for security reasons, for the safety of the troops."[133]

Bahrani also reported that in the summer of 2004, "the wall of the Temple of Nabu and the roof of the Temple of Ninmah, both sixth century BC, collapsed as a result of the movement of helicopters."[133] Electrical power is scarce in post-war Iraq, Bahrani reported, and some fragile artifacts, including the Ottoman Archive, would not survive the loss of refrigeration.[133]

Bush declares "End of major combat operations" (May 2003)

On May 1, 2003, Bush landed on the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln, in a Lockheed S-3 Viking, where he gave a speech announcing the end of major combat operations in the Iraq war. Bush's landing was criticized by opponents as an overly theatrical and expensive stunt. Clearly visible in the background was a banner stating "Mission Accomplished." The banner, made by White House staff and supplied by request of the United States Navy,[134] was criticized as premature - especially as sectarian violence and American casualties have continued to increase since the official end of hostilities. The White House subsequently released a statement that the sign and Bush's visit referred to the initial invasion of Iraq and disputing the claim of theatrics. The speech itself noted: "We have difficult work to do in Iraq. We are bringing order to parts of that country that remain dangerous."[135]

Post-invasion Iraq has been marked by violent conflict between U.S.-led soldiers and forces described by the occupiers as insurgents. The ongoing resistance in Iraq was concentrated in, but not limited to, an area referred to by Western media and the occupying forces as the Sunni triangle and Baghdad.[136]

This resistance may be described as guerrilla warfare. The tactics in use were to include mortars, suicide bombers, roadside bombs, small arms fire, improvised explosive devices (IED's), and handheld antitank grenade-launchers (RPG's), as well as sabotage against the oil infrastructure. There are also accusations, questioned by some, about attacks toward the power and water infrastructure.

There is evidence that some of the resistance was organized, perhaps by the fedayeen and other Saddam Hussein or Ba'ath loyalists, religious radicals, Iraqis angered by the occupation, and foreign fighters.[137]

According to a survey 2006 study conducted by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, more than 601,000 Iraqis have died in the violence following the 2003 invasion.[138]

Casualties

Death toll

While estimates on the number of casualties during the invasion in Iraq vary widely, the majority of deaths and injuries have occurred after U.S. President Bush declared the end of "major combat operations" on May 1, 2003.[139] According to CNN, the U.S. government reported that 139 American military personnel were killed before May 1, 2003, while over 4,000 have been killed since 2003.[139] Estimates on civilian casualties are more variable than those for military personnel. According to Iraq Body Count, a group that relies on Western press reports to measure civilian casualties, approximately 7,500 civilians were killed during the invasion phase, while more than 60,000 civilians have been killed as of April 2007.[140]

In November 2006 Iraq's Health Minister Ali al-Shemari said that since the March 2003 invasion between 100,000 and 150,000 Iraqis have been killed.[141] Al-Shemari based his figure on an estimate of 100 bodies per day brought to morgues and hospitals – such a calculation would come out closer to 130,000 in total.[142]