Canada – United States border

The Canada – United States border is the international border between Canada and the United States. Officially known as the International Boundary, it is the longest common border in the world and is unmilitarized. The terrestrial boundary (including small portions of maritime boundaries on the Atlantic, Pacific, and Arctic coasts, as well as the Great Lakes) is 8,891 kilometres (5,525 mi) long, including 2,475 kilometres (1,538 mi) shared with Alaska.

Contents |

History

-

For more details on this topic, see Aroostook War, Oregon boundary dispute and Alaska boundary dispute.

The present border originated with the Treaty of Paris in 1783, which ended the war between Great Britain and the separating colonies which would form the United States. The Jay Treaty of 1794 created the International Boundary Commission, which was charged with surveying and mapping the boundary. Westward expansion of both British North America and the United States saw the boundary extended west along the 49th parallel from the Northwest Angle at Lake of the Woods to the Rocky Mountains under the Convention of 1818. This convention extinguished British claims south of that latitude to the Red River Valley, which was part of Rupert's Land; it also extinguished U.S. claims to land north of that line in the watershed of the Missouri River, which was part of the Louisiana Purchase.[1]

Disputes over the interpretation of boundary demarcation led to the Aroostook War and the ensuing Webster–Ashburton Treaty in 1842, which better defined the boundary between Maine and New Brunswick and the Province of Canada, as well as the border along the Boundary Waters in present day Ontario and Minnesota between Lake Superior and the Northwest Angle.[2][1]

An 1844 boundary dispute during U.S. President James K. Polk's administration led to a call for the northern boundary of the U.S. west of the Rockies to be latitude 54° 40' north (related to the southern boundary of Russia's Alaska Territory), but the United Kingdom wanted a border that followed the Columbia River to the Pacific Ocean. The dispute was resolved in the Oregon Treaty of 1846, which established the 49th parallel as the boundary through the Rockies. The Northwest Boundary Survey (1857–61) laid out the land boundary, but the water boundary was not settled for some time. After the Pig War in 1859, the San Juan Islands were given to the United States. In 1903 a joint United Kingdom – Canada – U.S. tribunal established the boundary with Alaska, much of which follows the 141st meridian west.

International Boundary Commission

In 1925, the International Boundary Commission was made a permanent organization responsible for surveying and mapping the boundary, maintaining boundary monuments (and buoys where applicable), as well as keeping the boundary clear of brush and vegetation for 6 metres (20 ft). This "boundary vista" extends for 3 metres (10 ft) on each side of the line. The Commission's annual budget is about $1.4 million (USD).[3]

The commission is headed by two commissioners, one of whom is Canadian, the other American.[4] In July 2007, the Bush Administration told the U.S. Commissioner, Dennis Schornack, that he was fired. Schornack rejected the dismissal, saying that the commission is an independent, international organization outside the U.S. government's jurisdiction, and that according to the 1908 treaty that created it, a vacancy can only be created by "the death, resignation or other disability" of a commissioner.[5] The Canadian government said that it was taking no position on the matter,[6] but Peter Sullivan, the Canadian commissioner, said on July 13 that he was ready to work with David Bernhardt, a Colorado-based solicitor of the Department of the Interior, who was designated as the acting U.S. commissioner by President Bush.[7]

Security

Law enforcement approach

Commonly referred to as the world's longest undefended border, the International Boundary is actually defended, but by law enforcement and not military personnel. The relatively low level of security measures stands in contrast to that of the United States – Mexico border (one-third as long as the Canada–U.S. border), which is actively patrolled by U.S. customs and immigration personnel to prevent illegal migration and drug trafficking.

Parts of the International Boundary cross through mountainous terrain or heavily forested areas, but significant portions also cross remote prairie farmland and the Great Lakes and Saint Lawrence River, in addition to the maritime components of the boundary at the Atlantic, Pacific, and Arctic oceans. The border also runs through the middle of the Akwesasne Nation and even divides some buildings found in communities in Vermont and Quebec whose construction pre-dated the border's delineation.

The actual number of U.S. and Canadian border security personnel is classified. In comparison, there are in excess of 11,000 U.S. Border Patrol personnel on the Mexico–U.S. border alone.

Following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks in the United States, border security along the International Boundary was dramatically tightened by both nations in both populated and rural areas. Both nations are also actively involved in detailed and extensive tactical and strategic intelligence sharing. It is a common misconception that the 19 terrorists involved in the September 11 attacks entered the United States via the Canadian border.[8]

Security measures

Residents of both nations who own property adjacent to the border are required to report construction of any physical border crossing on their land to their respective governments, and this is enforced by the International Boundary Commission. Where required, fences or vehicle blockades are used. All persons crossing the border are required to report to the respective customs and immigration agencies in each country. In remote areas where staffed border crossings are not available, there are hidden sensors on roads and also scattered in wooded areas near crossing points and on many trails and railways, but there are not enough border personnel on either side to verify and stop coordinated incursions.

Smuggling

In past years Canadian officials have complained of drug, cigarette and firearms smuggling from the United States while U.S. officials have complained of drug smuggling from Canada. Human smuggling into both countries has been an ongoing problem for border security and law enforcement personnel, although a minor one in comparison to the Mexico–U.S. border.

In July 2005, law enforcement personnel arrested three men who had built a 360-foot (110 m) tunnel under the border between British Columbia and Washington that they intended to use for smuggling marijuana, the first such tunnel known on this border.[9]

Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative (WHTI)

The United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS) enforces rules regarding identification requirements for U.S. citizens and international travellers entering the country. This final rule and first phase of the Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative establishes four forms of identification—a valid passport, Alien Registration Card, NEXUS Air card, or U.S. Military Orders—required to enter the US by air.[10][11]

Requirements for all persons arriving through land and sea ports-of-entry (including ferries) are not finalized, but DHS has announced that as of June 2009 all individuals crossing the border via land will be required to present a valid passport or other documents as determined by DHS. The final rule relating to land and sea travel will be addressed in a separate, future rule making.

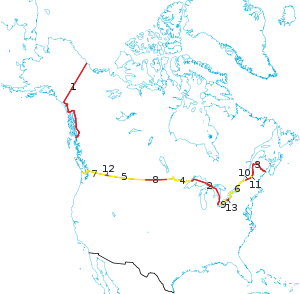

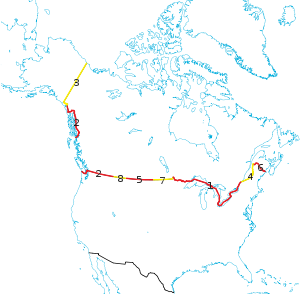

Border lengths

|

|

|||||

| Rank | State | Length of Border with Canada | Rank | Province | Length of Border with the U.S. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alaska | 2,475 km (1,538 mi) | 1 | Ontario | 2,760 km (1,715 mi) | |

| 2 | Michigan | 1,160 km (721 mi) | 2 | British Columbia | 2,168 km (1,347 mi) | |

| 3 | Maine | 983 km (611 mi) | 3 | Yukon | 1,210 km (752 mi) | |

| 4 | Minnesota | 880 km (547 mi) | 4 | Quebec | 813 km (505 mi) | |

| 5 | Montana | 877 km (545 mi) | 5 | Saskatchewan | 632 km (393 mi) | |

| 6 | New York | 716 km (445 mi) | 6 | New Brunswick | 513 km (318 mi) | |

| 7 | Washington | 687 km (427 mi) | 7 | Manitoba | 497 km (309 mi) | |

| 8 | North Dakota | 499 km (310 mi) | 8 | Alberta | 298 km (185 mi) | |

| 9 | Ohio | 235 km (146 mi) | ||||

| 10 | Vermont | 145 km (90 mi) | ||||

| 11 | New Hampshire | 93 km (58 mi) | ||||

| 12 | Idaho | 72 km (45 mi) | ||||

| 13 | Pennsylvania | 68 km (42 mi) | ||||

Notable bridge/tunnel crossings

- Fort Frances-International Falls International Bridge – Fort Frances, Ontario and International Falls, Minnesota

- Baudette-Rainy River International Bridge – Baudette, Minnesota and Rainy River, Ontario

- Sault Ste. Marie International Bridge – Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan and Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario

- Blue Water Bridge – Port Huron, Michigan and Sarnia, Ontario

- St. Clair Tunnel

- Detroit–Windsor Tunnel – Windsor, Ontario and Detroit, Michigan

- Michigan Central Railway Tunnel – Windsor, Ontario and Detroit, Michigan

- Ambassador Bridge – Windsor, Ontario and Detroit, Michigan

- Peace Bridge – Fort Erie, Ontario and Buffalo, New York

- Whirlpool Rapids Bridge – Niagara Falls, Ontario and Niagara Falls, New York

- Rainbow Bridge – Niagara Falls, Ontario and Niagara Falls, New York

- Queenston-Lewiston Bridge – Queenston, Ontario and Lewiston, New York

- Thousand Islands Bridge – Wellesley Island, New York and Hill Island, Ontario

- Ogdensburg-Prescott International Bridge – Ogdensburg, New York and Johnstown, Ontario

- Three Nations Crossing – Cornwall, Ontario and Massena, New York

Other border crossings (airports, seaports)

The U.S. maintains immigration offices, called "pre-clearance facilities", in Canadian airports with international air service to the United States (Calgary, Edmonton, Halifax, Montreal, Ottawa, Toronto, Vancouver, and Winnipeg). This expedites travel by allowing flights originating in Canada to land at a U.S. airport without being processed as an international arrival. Similar arrangements exist at major Canadian seaports which handle sealed direct import shipments into the United States. Canada does not maintain equivalent personnel at U.S. airports due to the sheer number of destinations served by Canadian airlines and the limited number of flights compared to the number of US-bound flights that depart major Canadian airports. Additionally, at Vancouver's Pacific Central Station, passengers are required to pass through U.S. pre-clearance facilities and pass their baggage through an x-ray before being allowed to board the Seattle-bound Amtrak Cascades train, which makes no further stops before crossing the border. Pre-clearance facilities are not available for the popular New York City to Montreal (Adirondack) or Toronto (Maple Leaf) lines, as these lines have stops between Montreal or Toronto and the border. Instead, passengers must clear customs at a stop located at the actual border.

Several ocean-based ferry services operate between the provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia to the state of Maine, as well as between the province of British Columbia and the states of Washington and Alaska. There are also several ferry services in the Great Lakes operating between the province of Ontario and the states of Michigan, New York, and Ohio.

Cross-border airports

One curiosity on the Canada–US border is the presence of three airports that actually straddle the borderline—Piney Pinecreek Border Airport in Manitoba and Minnesota, Coronach/Scobey Border Station Airport in Saskatchewan and Montana, and Avey Field State Airport in Washington and British Columbia. Each of these airports is adjacent to a border crossing. The runways at Piney Pinecreek and Avey Field run roughly north/south and cross the border; Coronach/Scobey's runway runs east/west, directly along the border itself.

Remaining boundary disputes

- Machias Seal Island and North Rock (Maine / New Brunswick)

- Dixon Entrance (Alaska / British Columbia)

- Beaufort Sea (Alaska/Yukon)

- Strait of Juan de Fuca (Washington / British Columbia)

See also

- List of Canada – United States border crossings

- American entry into Canada by land

- Canada – United States relations

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Lass, William E. (1980). Minnesota's Boundary with Canada. St. Paul, Minnesota: Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 0-8735-1153-0.

- ↑ "Webster-Ashburton Treaty". Yale Law School (1842). Retrieved on 2007-03-01.

- ↑ Stacy Schiff, "Politics Starts at the Border", New York Times, July 22, 2007

- ↑ Organization Chart, International Boundary Commission, accessed July 27, 2007

- ↑ David Bowermaster, "Firing by Bush rejected by boundary official", Seattle Times, July 12, 2007

- ↑ Petti Fong, "Politics delineates boundary dispute: U.S. couple's retaining wall overlooking Canada has sparked legal battle over presidential power", Toronto Star, July 26, 2007

- ↑ "Fired border official's job filled quickly: White House refuses comment on former bureaucrat involved in lawsuit over couple's fence", Globe and Mail, July 13, 2007

- ↑ Wendell Sanford, Consul of Canada, Remarks for an Address, Canadian Studies Program, University of California at Berkeley, October 9, 2002

- ↑ Terry Frieden, "Drug tunnel found under Canada border: Five arrests made after agents monitored construction", CNN, July 22, 2006

- ↑ DHS Announces Final Western Hemisphere Air Travel Rule, 5 December 2006, http://www.acte.org/resources/view_article.php?id=105, retrieved on 2007-12-02

- ↑ Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative: The Basics, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, http://www.dhs.gov/xtrvlsec/crossingborders/whtibasics.shtm, retrieved on 2007-12-02

External links