Inertial frame of reference

In physics, an inertial frame of reference is a frame of reference which belongs to a set of frames in which physical laws hold in the same and simplest form. According to the first postulate of special relativity, all physical laws take their simplest form in an inertial frame, and there exist multiple inertial frames interrelated by uniform translation: [1]

Special principle of relativity: If a system of coordinates K is chosen so that, in relation to it, physical laws hold good in their simplest form, the same laws hold good in relation to any other system of coordinates K' moving in uniform translation relatively to K.

– Albert Einstein: The foundation of the general theory of relativity, Section A, §1

The principle of simplicity can be used within Newtonian physics as well as in special relativity; see Nagel[2] and also Blagojević.[3]

The laws of Newtonian mechanics do not always hold in their simplest form...If, for instance, an observer is placed on a disc rotating relative to the earth, he/she will sense a 'force' pushing him/her toward the periphery of the disc, which is not caused by any interaction with other bodies. Here, the acceleration is not the consequence of the usual force, but of the so-called inertial force. Newton's laws hold in their simplest form only in a family of reference frames, called inertial frames. This fact represents the essence of the Galilean principle of relativity:

The laws of mechanics have the same form in all inertial frames.– Milutin Blagojević: Gravitation and Gauge Symmetries, p. 4

In practical terms, the equivalence of inertial reference frames means that scientists within a box moving uniformly cannot determine their absolute velocity by any experiment (otherwise the differences would set up an absolute standard reference frame).[4][5] According to this definition, supplemented with the constancy of the speed of light, inertial frames of reference transform among themselves according to the Poincaré group of symmetry transformations, of which the Lorentz transformations are a subgroup.[6]

The expression inertial frame of reference (German: Inertialsystem) was coined by Ludwig Lange in 1885, to replace Newton's definitions of "absolute space and time" by a more operational definition.[7][8] As referenced by Iro, Lange proposed:[9]

A reference frame in which a mass point thrown from the same point in three different (non co-planar) directions follows rectilinear paths each time it is thrown, is called an inertial frame.

– L. Lange (1885) as quoted by Max von Laue in his book (1921) Die Relativitätstheorie, p. 34, and translated by Iro

A discussion of Lange's proposal can be found in Mach.[10]

The inadequacy of the notion of "absolute space" in Newtonian mechanics is spelled out by Blagojević:[11]

*The existence of absolute space contradicts the internal logic of classical mechanics since, according to Galilean principle of relativity, none of the inertial frames can be singled out.

*Absolute space does not explain inertial forces since they are related to acceleration with respect to any one of the inertial frames.

*Absolute space acts on physical objects by inducing their resistance to acceleration but it cannot be acted upon.– Milutin Blagojević: Gravitation and Gauage Symmetries, p. 5

The utility of operational definitions was carried much further in the special theory of relativity.[12] Some historical background including Lange's definition is provided by DiSalle, who says in summary: [13]

The original question, “relative to what frame of reference do the laws of motion hold?” is revealed to be wrongly posed. For the laws of motion essentially determine a class of reference frames, and (in principle) a procedure for constructing them.

Contents |

Newton's inertial frame of reference

. Frame S' has an arbitrary but fixed rotation with respect to frame S. They are both inertial frames provided a body not subject to forces appears to move in a straight line. If that motion is seen in one frame, it will also appear that way in the other.

. Frame S' has an arbitrary but fixed rotation with respect to frame S. They are both inertial frames provided a body not subject to forces appears to move in a straight line. If that motion is seen in one frame, it will also appear that way in the other.Within the realm of Newtonian mechanics, an inertial frame of reference, or inertial reference frame, is one in which Newton's first law of motion is valid.[14] However, the principle of special relativity generalizes the notion of inertial frame to include all physical laws, not simply Newton's first law.

Newton viewed the first law as valid in any reference frame moving with uniform velocity relative to the fixed stars;[15] that is, neither rotating nor accelerating relative to the stars.[16] Today the notion of "absolute space" is abandoned, and an inertial frame in the field of classical mechanics is defined as:[17][18]

An inertial frame of reference is one in which the motion of a particle not subject to forces is in a straight line at constant speed.

Hence, with respect to an inertial frame, an object or body accelerates only when a physical force is applied, and (following Newton's first law of motion), in the absence of a net force, a body at rest will remain at rest and a body in motion will continue to move uniformly—that is, in a straight line and at constant speed. Newtonian inertial frames transform among each other according to the Galilean group of symmetries.

If this rule is interpreted as saying that straight-line motion is an indication of zero net force, the rule does not identify inertial reference frames, because straight-line motion can be observed in a variety of frames. If the rule is interpreted as defining an inertial frame, then we have to be able to determine when zero net force is applied. The problem was summarized by Einstein:[19]

The weakness of the principle of inertia lies in this, that it involves an argument in a circle: a mass moves without acceleration if it is sufficiently far from other bodies; we know that it is sufficiently far from other bodies only by the fact that it moves without acceleration.

– Albert Einstein: The Meaning of Relativity, p. 58

There are several approaches to this issue. One approach is to argue that all real forces drop off with distance from their sources in a known manner, so we have only to be sure that we are far enough away from all sources to insure that no force is present.[20] A possible issue with this approach is the historically long-lived view that the distant universe might affect matters (Mach's principle). Another approach is to identify all real sources for real forces and account for them. A possible issue with this approach is that we might miss something, or account inappropriately for their influence (Mach's principle again?). A third approach is to look at the way the forces transform when we shift reference frames. Fictitious forces, those that arise due to the acceleration of a frame, disappear in inertial frames, and have complicated rules of transformation in general cases. On the basis of universality of physical law and the request for frames where the laws are most simply expressed, inertial frames are distinguished by the absence of such fictitious forces.

Newton enunciated a principle of relativity himself in one of his corollaries to the laws of motion:[21][22]

The motions of bodies included in a given space are the same among themselves, whether that space is at rest or moves uniformly forward in a straight line.

– Isaac Newton: Principia, Corollary V, p. 88 in Andrew Motte translation

This principle differs from the special principle in two ways: first, it is restricted to mechanics, and second, it makes no mention of simplicity. It shares with the special principle the invariance of the form of the description among mutually translating reference frames.[23] The role of fictitious forces in classifying reference frames is pursued further below.

Non-inertial reference frames

- See also: Non-inertial frame and Rotating spheres

Inertial and non-inertial reference frames can be distinguished by the absence or presence of fictitious forces, as explained shortly.[24][25]

The effect of his being in the noninertial frame is to require the observer to introduce a fictitious force into his calculations….

– Sidney Borowitz and Lawrence A Bornstein in A Contemporary View of Elementary Physics, p. 138

The presence of fictitious forces indicates the physical laws are not the simplest laws available so, in terms of the special principle of relativity, a frame where fictitious forces are present is not an inertial frame:[26]

The equations of motion in an non-inertial system differ from the equations in an inertial system by additional terms called inertial forces. This allows us to detect experimentally the non-inertial nature of a system.

– V. I. Arnol'd: Mathematical Methods of Classical Mechanics Second Edition, p. 129

Bodies in non-inertial reference frames are subject to so-called fictitious forces (pseudo-forces); that is, forces that result from the acceleration of the reference frame itself and not from any physical force acting on the body. Examples of fictitious forces are the centrifugal force and the Coriolis force in rotating reference frames.

How then, are "fictitious' forces to be separated from "real" forces? It is hard to apply the Newtonian definition of an inertial frame without this separation. For example, consider a stationary object in an inertial frame. Being at rest, no net force is applied. But in a frame rotating about a fixed axis, the object appears to move in a circle, and is subject to centripetal force (which is made up of the Coriolis force and the centrifugal force). How can we decide that the rotating frame is a non-inertial frame? There are two approaches to this resolution: one approach is to look for the origin of the fictitious forces (the Coriolis force and the centrifugal force). We will find there are no sources for these forces, no originating bodies.[27] A second approach is to look at a variety of frames of reference. For any inertial frame, the Coriolis force and the centrifugal force disappear, so application of the principle of special relativity would identify these frames where the forces disappear as sharing the same and the simplest physical laws, and hence rule that the rotating frame is not an inertial frame.

Newton examined this problem himself using rotating spheres, as shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. He pointed out that if the spheres are not rotating, the tension in the tying string is measured as zero in every frame of reference.[28] If the spheres only appear to rotate (that is, we are watching stationary spheres from a rotating frame), the zero tension in the string is accounted for by observing that the centripetal force is supplied by the centrifugal and Coriolis forces in combination, so no tension is needed. If the spheres really are rotating, the tension observed is exactly the centripetal force required by the circular motion. Thus, measurement of the tension in the string identifies the inertial frame: it is the one where the tension in the string provides exactly the centripetal force demanded by the motion as it is observed in that frame, and not a different value. That is, the inertial frame is the one where the fictitious forces vanish. (See Rotating spheres for original text and mathematical formulation.)

So much for fictitious forces due to rotation. However, for linear acceleration, Newton expressed the idea of undetectability of straight-line accelerations held in common:[22]

If bodies, any how moved among themselves, are urged in the direction of parallel lines by equal accelerative forces, they will continue to move among themselves, after the same manner as if they had been urged by no such forces.

– Isaac Newton: Principia Corollary VI, p. 89, in Andrew Motte translation

This principle generalizes the notion of an inertial frame. For example, an observer confined in a free-falling lift will assert that he himself is a valid inertial frame, even if he is accelerating under gravity, so long as he has no knowledge about anything outside the lift. So, strictly speaking, inertial frame is a relative concept. With this in mind, we can define inertial frames collectively as a set of frames which are stationary or moving at constant velocity with respect to each other, so that a single inertial frame is defined as an element of this set.

For these ideas to apply, everything observed in the frame has to be subject to a base-line, common acceleration shared by the frame itself. That situation would apply, for example, to the elevator example, where all objects are subject to the same gravitational acceleration, and the elevator itself accelerates at the same rate.

Newtonian mechanics

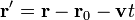

Classical mechanics, which includes relativity, assumes the equivalence of all inertial reference frames. Newtonian mechanics makes the additional assumptions of absolute space and absolute time. Given these two assumptions, the coordinates of the same event (a point in space and time) described in two inertial reference frames are related by a Galilean transformation

where  and

and  represent shifts in the origin of space and time, and

represent shifts in the origin of space and time, and  is the relative velocity of the two inertial reference frames. Under Galilean transformations, the time between two events (

is the relative velocity of the two inertial reference frames. Under Galilean transformations, the time between two events ( ) is the same for all inertial reference frames and the distance between two simultaneous events (or, equivalently, the length of any object,

) is the same for all inertial reference frames and the distance between two simultaneous events (or, equivalently, the length of any object,  ) is also the same.

) is also the same.

Special relativity

Einstein's theory of special relativity, like Newtonian mechanics, assumes the equivalence of all inertial reference frames, but makes an additional assumption, foreign to Newtonian mechanics, namely, that in free space light always is propagated with the speed of light c0, a defined value independent of its direction of propagation and its frequency, and also independent of the state of motion of the emitting body. This second assumption has been verified experimentally and leads to counter-intuitive deductions including:

- time dilation (moving clocks tick more slowly)

- length contraction (moving objects are shortened in the direction of motion)

- relativity of simultaneity (simultaneous events in one reference frame are not simultaneous in almost all frames moving relative to the first).

These deductions are logical consequences of the stated assumptions, and are general properties of space-time, not properties pertaining to the structure of individual objects like atoms or stars, nor to the mechanisms of clocks.

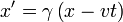

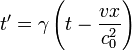

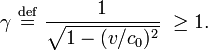

These effects are expressed mathematically by the Lorentz transformation

where shifts in origin have been ignored, the relative velocity is assumed to be in the  -direction and the Lorentz factor γ is defined by:

-direction and the Lorentz factor γ is defined by:

The Lorentz transformation is equivalent to the Galilean transformation in the limit c0 → ∞ (a hypothetical case) or v → 0 (low speeds).

Under Lorentz transformations, the time and distance between events may differ among inertial reference frames; however, the Lorentz scalar distance s2 between two events is the same in all inertial reference frames

From this perspective, the speed of light is only accidentally a property of light, and is rather a property of spacetime, a conversion factor between conventional time units (such as seconds) and length units (such as meters).

Incidentally, because of the limitations on speeds faster than the speed of light, notice that a rotating frame of reference (which is a non-inertial frame, of course) cannot be used out to arbitrary distances because at large radius its components would move faster than the speed of light. See Landau and Lifshitz.[29]

General relativity

- See also: Equivalence principle and Eötvös experiment

General relativity is based upon the principle of equivalence:[30][31]

The principle of equivalence: There is no experiment observers can perform to distinguish whether an acceleration arises because of a gravitational force or because their reference frame is accelerating

– Douglas C. Giancoli Physics for Scientists and Engineers with Modern Physics, p. 155

This idea was introduced in Einstein's 1907 article "Principle of Relativity and Gravitation" and later developed in 1911.[32] Support for this principle is found in the Eötvös experiment, which determines whether the ratio of inertial to gravitational mass is the same for all bodies, regardless of size or composition. To date no difference has been found to a few parts in 1011.[33] For some discussion of the subtleties of the Eötvös experiment, such as the local mass distribution around the experimental site (including a quip about the mass of Eötvös himself), see Franklin.[34]

Einstein’s general theory modifies the distinction between nominally "inertial" and "noninertial" effects by replacing special relativity's "flat" Euclidean geometry with a curved non-Euclidean metric. In general relativity, the principle of inertia is replaced with the principle of geodesic motion, whereby objects move in a way dictated by the curvature of spacetime. As a consequence of this curvature, it is not a given in general relativity that inertial objects moving at a particular rate with respect to each other will continue to do so. This phenomenon of geodesic deviation means that inertial frames of reference do not exist globally as they do in Newtonian mechanics and special relativity.

However, the general theory reduces to the special theory over sufficiently small regions of spacetime, where curvature effects become less important and the earlier inertial frame arguments can come back into play. Consequently, modern special relativity is now sometimes described as only a “local theory”. (However, this refers to the theory’s application rather than to its derivation.)

References

- ↑ Einstein, A., Lorentz, H. A., Minkowski, H., & Weyl, H. (1952). The Principle of Relativity: a collection of original memoirs on the special and general theory of relativity. Courier Dover Publications. p. 111. ISBN 0486600815. http://books.google.com/books?id=yECokhzsJYIC&pg=PA111&dq=postulate+%22Principle+of+Relativity%22&lr=&as_brr=0&sig=ACfU3U2GFu6cWo5WHzgumuNEqum_fBiTiw.

- ↑ Ernest Nagel (1979). The Structure of Science. Hackett Publishing. p. 212. ISBN 0915144719. http://books.google.com/books?id=u6EycHgRfkQC&pg=PA212&dq=inertial+%22Foucault%27s+pendulum%22&lr=&as_brr=0&sig=ACfU3U1jQDxKwQROE_XK3mxm7xXfTrwhpQ.

- ↑ Milutin Blagojević (2002). Gravitation and Gauge Symmetries. CRC Press. p. 4. ISBN 0750307676. http://books.google.com/books?id=N8JDSi_eNbwC&pg=PA5&dq=inertial+frame+%22absolute+space%22&lr=&as_brr=0&sig=ACfU3U2Vg9oaYzXo79yholm3opU9DRpwZA#PPA4,M1.

- ↑ Albert Einstein (1920). Relativity: The Special and General Theory. H. Holt and Company. p. 17. http://books.google.com/books?id=3H46AAAAMAAJ&printsec=titlepage&dq=%22The+Principle+of+Relativity%22&lr=&as_brr=0#PPA17,M1.

- ↑ Richard Phillips Feynman (1998). Six not-so-easy pieces: Einstein's relativity, symmetry, and space-time. Basic Books. p. 73. ISBN 0201328429. http://books.google.com/books?id=ipY8onVQWhcC&pg=PA49&dq=%22The+Principle+of+Relativity%22&lr=&as_brr=0&sig=ACfU3U3KfqkThK26GE7jG-QEFypFxJ17eQ#PPA73,M1.

- ↑ Armin Wachter & Henning Hoeber (2006). Compendium of Theoretical Physics. Birkhäuser. p. 98. ISBN 0387257993. http://books.google.com/books?id=j3IQpdkinxMC&pg=PA98&dq=%2210-parameter+proper+orthochronous+Poincare+group%22&lr=&as_brr=0&sig=ACfU3U1Q-OkzdJbWVxioMFRbl1MuYt6bPw.

- ↑ Lange, Ludwig (1885). "Über die wissenschaftliche Fassung des Galileischen Beharrungsgesetzes". Philosophische Studien 2.

- ↑ Julian B. Barbour (2001). The Discovery of Dynamics (Reprint of 1989 Absolute or Relative Motion? ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 645-646. ISBN 0195132025. http://books.google.com/books?id=WQidkYkleXcC&pg=PA645&dq=Ludwig+Lange+%22operational+definition%22&lr=&as_brr=0&sig=ACfU3U0mti8md3OKWLkQ7xm4Db1dqr6kjA#PPA646,M1.

- ↑ Harald Iro (2002). A Modern Approach to Classical Mechanics. World Scientific. p. p.169. ISBN 9812382135. http://books.google.com/books?id=-L5ckgdxA5YC&pg=PA179&dq=inertial+noninertial&lr=&as_brr=0&sig=ACfU3U3fCW68SLm1zalPZWi0LvLK4DrXYg#PPA169,M1.

- ↑ Ernst Mach (1915). The Science of Mechanics. The Open Court Publishing Co.. p. 38. http://books.google.com/books?id=cyE1AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA33&dq=rotating+sphere+Mach+cord+OR+string+OR+rod&lr=&as_brr=0#PPA38,M1.

- ↑ Milutin Blagojević (2002). Gravitation and Gauge Symmetries. CRC Press. p. 5. ISBN 0750307676. http://books.google.com/books?id=N8JDSi_eNbwC&pg=PA5&dq=inertial+frame+%22absolute+space%22&lr=&as_brr=0&sig=ACfU3U2Vg9oaYzXo79yholm3opU9DRpwZA#PPA5,M1.

- ↑ NMJ Woodhouse (2003). Special relativity. London: Springer. p. 58. ISBN 1-85233-426-6. http://books.google.com/books?id=tM9hic_wo3sC&pg=PA126&dq=Woodhouse+%22operational+definition%22&lr=&as_brr=0&sig=ACfU3U3at8NqLoJYAia9MZwvpqM4C7s9JQ.

- ↑ Robert DiSalle (Summer 2002). "Space and Time: Inertial Frames". in Edward N. Zalta. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2002/entries/spacetime-iframes/#Oth.

- ↑ C Møller (1976). The Theory of Relativity (Second Edition ed.). Oxford UK: Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 019560539X. http://worldcat.org/oclc/220221617&referer=brief_results.

- ↑ The question of "moving uniformly relative to what?" was answered by Newton as "relative to absolute space". As a practical matter, "absolute space" was considered to be the fixed stars. For a discussion of the role of fixed stars, see Henning Genz (2001). Nothingness: The Science of Empty Space. Da Capo Press. p. 150. ISBN 0738206105. http://books.google.com/books?id=Cn_Q9wbDOM0C&pg=PA150&dq=frame+Newton+%22fixed+stars%22&lr=&as_brr=0&sig=ACfU3U3BgdpcUhKWUTkXYsEUOi5gaFuanQ.

- ↑ Robert Resnick, David Halliday, Kenneth S. Krane (2001). Physics (5th Edition ed.). Wiley. Volume 1, Chapter 3. ISBN 0471320579. http://books.google.com/books?id=CucFAAAACAAJ&dq=intitle:physics+inauthor:resnick&lr=&as_brr=0.

- ↑ RG Takwale (1980). Introduction to classical mechanics. New Delhi: Tata McGraw-Hill. p. 70. ISBN 0070966176. http://books.google.com/books?id=r5P29cN6s6QC&pg=PA70&dq=fixed+stars+%22inertial+frame%22&lr=&as_brr=0&sig=60wXg5_82gzOo0JVzMtvDEn5XEY.

- ↑ NMJ Woodhouse (2003). Special relativity. London/Berlin: Springer. p. 6. ISBN 1-85233-426-6. http://books.google.com/books?id=ggPXQAeeRLgC&printsec=frontcover&dq=isbn=1852334266#PPA6,M1.

- ↑ A Einstein (1950). The Meaning of Relativity. Princeton University Press. p. 58. http://books.google.com/books?as_q=&num=10&btnG=Google+Search&as_epq=%22The+weakness+of+the+principle+of+inertia+lies+in+this%2C+that+it+involves+an+argument+in+a+circle%3A+a+mass+moves+without+acceleration+if+it+is+sufficiently+far+from+other+bodies%3B+we+know+that+it+is+sufficiently+far+from+other+bodies+only+by+the+fact+that+it+moves+without+acceleration.%22+&as_oq=&as_eq=&as_brr=0&lr=&as_vt=&as_auth=&as_pub=&as_sub=&as_drrb=c&as_miny=&as_maxy=&as_isbn=.

- ↑ William Geraint Vaughan Rosser (1991). Introductory Special Relativity. CRC Press. p. 3. ISBN 0850668387. http://books.google.com/books?id=zpjBEBbIjAIC&pg=PA94&dq=reference+%22laws+of+physics%22&lr=&as_brr=0&sig=ACfU3U3Ee_ApZCzqvj_Y7hOU3M01GnDZxg#PPA3,M1.

- ↑ Richard Phillips Feynman (1998). Six not-so-easy pieces: Einstein's relativity, symmetry, and space-time. Basic Books. p. 50. ISBN 0201328429. http://books.google.com/books?id=ipY8onVQWhcC&pg=PA49&dq=%22The+Principle+of+Relativity%22&lr=&as_brr=0&sig=ACfU3U3KfqkThK26GE7jG-QEFypFxJ17eQ#PPA50,M1.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 See the Principia on line at Andrew Motte Translation

- ↑ However, in the Newtonian system the Galilean transformation connects these frames and in the special theory of relativity the Lorentz transformation connects them. The two transformations agree for speeds of translation much less than the speed of light.

- ↑ Milton A. Rothman (1989). Discovering the Natural Laws: The Experimental Basis of Physics. Courier Dover Publications. p. 23. ISBN 0486261786. http://books.google.com/books?id=Wdp-DFK3b5YC&pg=PA23&vq=inertial&dq=reference+%22laws+of+physics%22&lr=&as_brr=0&source=gbs_search_s&cad=5&sig=ACfU3U33YE3keeD7lDVtQvt-ltW87Lsq2Q.

- ↑ Sidney Borowitz & Lawrence A. Bornstein (1968). A Contemporary View of Elementary Physics. McGraw-Hill. p. 138. http://books.google.com/books?as_q=&num=10&btnG=Google+Search&as_epq=The+effect+of+his+being+in+the+noninertial+frame+is+to+require+the+observer+to&as_oq=&as_eq=&as_brr=0&lr=&as_vt=&as_auth=&as_pub=&as_sub=&as_drrb=c&as_miny=&as_maxy=&as_isbn=.

- ↑ V. I. Arnol'd (1989). Mathematical Methods of Classical Mechanics. Springer. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-387-96890-2. http://books.google.com/books?as_q=&num=10&btnG=Google+Search&as_epq=additional+terms+called+inertial+forces.+This+allows+us+to+detect+experimentally&as_oq=&as_eq=&as_brr=0&lr=&as_vt=&as_auth=&as_pub=&as_sub=&as_drrb=c&as_miny=&as_maxy=&as_isbn=.

- ↑ For example, there is no body providing a gravitational or electrical attraction.

- ↑ That is, the universality of the laws of physics requires the same tension to be seen by everybody. For example, it cannot happen that the string breaks under extreme tension in one frame of reference and remains intact in another frame of reference, just because we choose to look at the string from a different frame.

- ↑ LD Landau & LM Lifshitz (1975). The Classical Theory of Fields (4rth Revised English Edition ed.). Pergamon Press. p. 273-274. ISBN 978-0-7506-2768-9.

- ↑ David Morin (2008). Introduction to Classical Mechanics. Cambridge University Press. p. 649. ISBN 0521876222. http://books.google.com/books?id=Ni6CD7K2X4MC&pg=PA469&dq=acceleration+azimuthal+inauthor:Morin&lr=&as_brr=0#PPA649,M1.

- ↑ Douglas C. Giancoli (2007). Physics for Scientists and Engineers with Modern Physics. Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 155. ISBN 0131495089. http://books.google.com/books?id=xz-UEdtRmzkC&pg=PA155&dq=%22principle+of+equivalence%22&lr=&as_brr=0&sig=ACfU3U1ECpntiAMb3nvSw5WmTmKSK2Vqyw.

- ↑ A. Einstein, "On the influence of gravitation on the propagation of light", Annalen der Physik, vol. 35, (1911) : 898-908

- ↑ National Research Council (US) (1986). Physics Through the Nineteen Nineties: Overview. National Academies Press. p. 15. ISBN 0309035791. http://books.google.com/books?id=Hk1wj61PlocC&pg=PA15&dq=equivalence+gravitation&lr=&as_brr=0&sig=ACfU3U3Yv2jH-RWbdEgxp_Z9BDZPnTFgSg.

- ↑ Allan Franklin (2007). No Easy Answers: Science and the Pursuit of Knowledge. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 66. ISBN 0822959682. http://books.google.com/books?id=_RN-v31rXuIC&pg=PA66&dq=%22Eotvos+experiment%22&lr=&as_brr=0&sig=ACfU3U21h60xyvDwPRzyDEw83saJr9PzzQ.

Further reading

- Edwin F. Taylor and John Archibald Wheeler, Spacetime Physics, 2nd ed. (Freeman, NY, 1992)

- Albert Einstein, Relativity, the special and the general theories, 15th ed. (1954)

- Henri Poincaré, (1900) "La theorie de Lorentz et la Principe de Reaction", Archives Neerlandaises, V, 253–78.

- Albert Einstein, On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies, included in The Principle of Relativity, page 38. Dover 1923

External links

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry

- Animation clip showing scenes as viewed from both an inertial frame and a rotating frame of reference, visualizing the Coriolis and centrifugal forces.

See also

|

|

|