Inclination

Inclination in general is the angle between a reference plane and another plane or axis of direction. The axial tilt is expressed as the angle made by the planet's axis and a line drawn through the planet's center perpendicular to the orbital plane.

Contents |

Orbits

In particular, the inclination is one of the six orbital parameters describing the shape and orientation of a celestial orbit. It is the angular distance of the orbital plane from the plane of reference (usually the primary's equator or the ecliptic), normally stated in degrees.

In the solar system, the inclination (i in figure 1, below) of the orbit of a planet is defined as the angle between the plane of the orbit of the planet and the ecliptic —which is the plane containing Earth's orbital path. It could be measured with respect to another plane, such as the Sun's equator or even Jupiter's orbital plane, but the ecliptic is more practical for Earth-bound observers. Most planetary orbits in our solar system have relatively small inclinations, both in relation to each other and to the Sun's equator. There are notable exceptions in the dwarf planets Pluto and Eris, which have inclinations to the ecliptic of 17 degrees and 44 degrees respectively, and the large asteroid Pallas, which is inclined at 34 degrees. Many of the currently known extrasolar planets are in multiple systems, and sometimes have high inclinations. However, the inclinations for most extrasolar planets were not measured, leaving only their minimum masses, which means that some of the extrasolar planets may actually be a brown dwarfs or even dim red dwarf stars. So only transiting planets and planets detected by astrometry have known inclinations and hence true masses. Sometimes in 2010s, the inclinations and hence true masses for almost all the exoplanets will be measured by the number of observatories in space, including the Gaia mission, Space Interferometry Mission, and James Webb Space Telescope.

The inclination of orbits of natural or artificial satellites is measured relative to the equatorial plane of the body they orbit if they do so close enough. The equatorial plane is the plane perpendicular to the axis of rotation of the central body.

- an inclination of 0 degrees means the orbiting body orbits the planet in its equatorial plane, in the same direction as the planet rotates;

- an inclination of 90 degrees indicates a polar orbit, in which the spacecraft passes over the north and south poles of the planet; and

- an inclination of 180 degrees indicates a retrograde equatorial orbit.

For objects farther away from the central body, another reference plane is often used: the Laplace plane. As one moves away from the primary, the Laplace plane starts off in its equatorial plane and then gradually tilts away from that plane until it merges with the primary's orbital plane at great distances.

For objects where the primary's axis of rotation is unknown or poorly known, a satellite's inclination will be given with respect to the ecliptic, or sometimes (for slow-moving objects) with respect to the plane of the sky (see the definition given for binary stars, below).

For the Moon, measuring its inclination with respect to Earth's equatorial plane leads to a rapidly varying quantity and it makes more sense to measure it with respect to the ecliptic (i.e. the plane of the orbit that Earth and Moon track together around the Sun), a fairly constant quantity.

Other meanings

- For planets and other rotating celestial bodies, the angle of the axis of rotation with respect to the normal to plane of the orbit is sometimes also called inclination, but is better referred to as the axial tilt or obliquity.

- In particular, for the Earth, the obliquity of the ecliptic is the angle between the plane of the ecliptic and the equator.

- The inclination of objects beyond the solar system, such as a binary star, is defined as the angle between the normal to the orbital plane (i.e. the orbital axis) and the direction to the observer, since no other reference is available. Equivalently, this can be defined as the angle between the orbital plane and the plane of the sky. The latter depends on the direction in which an observer looks, so one has to be careful when comparing stars in different regions of the celestial sphere. Binary stars with inclinations close to 90 degrees (edge-on) are often eclipsing.

Calculation

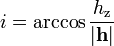

In astrodynamics, the inclination  can be computed as follows:

can be computed as follows:

where:

is z-component of

is z-component of  ,

, is orbital momentum vector perpendicular to the orbital plane.

is orbital momentum vector perpendicular to the orbital plane.

See also

- Kepler orbits

- Altitude (astronomy)

- Axial tilt

- Azimuth

- Kozai effect

- Orbital inclination change

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Inclination

Inclination Longitude of the ascending node

Longitude of the ascending node

Semi-major axis

Semi-major axis Mean anomaly at

Mean anomaly at  True anomaly

True anomaly Semi-minor axis

Semi-minor axis

Eccentric anomaly

Eccentric anomaly Mean longitude

Mean longitude True longitude

True longitude