Hydrolysis

Hydrolysis is a chemical reaction during which one or more water molecules are split into hydrogen and hydroxide ions which may go on to participate in further reactions.[1][2] It is the type of reaction that is used to break down certain polymers, especially those made by step-growth polymerization. Such polymer degradation is usually catalysed by either acid or alkali attack, often increasing with their strength or pH.

Hydrolysis is distinct from hydration, where hydrated molecule does not "lyse" (break into two new compounds). It should not be confused with hydrogenolysis, a reaction of hydrogen.

Contents |

Types

In organic chemistry, considered as the reverse or opposite of condensation, a reaction in which two molecular fragments are joined for each water molecule produced. As hydrolysis may be a reversible reaction, condensation and hydrolysis can take place at the same time, with the position of equilibrium determining the amount of each product. A typical example is the hydrolysis of an ester to an acid and an alcohol.

- R1CO2R2 + H2O ⇌ R1CO2H + R2OH

In inorganic chemistry, the word is often applied to solutions of salts and the reactions by which they are converted to new ionic species or to precipitates (oxides, hydroxides, or salts). The addition of a molecule of water to a chemical compound, without forming any other products is usually known as hydration, rather than hydrolysis.

In biochemistry, hydrolysis is considered the reverse or opposite of dehydration synthesis. In hydrolysis, a water molecule (H2O), is added, whereas in dehydration synthesis, a molecule of water is removed.

In electrochemistry, hydrolysis can also refer to the electrolysis of water. In hydrolysis, a voltage is applied across an aqueous medium, which produces a current and breaks the water into its constituents, hydrogen and oxygen.

In organic chemistry, a development announced in 2008 provided a method of splitting water atoms using photocatalysis. An enzyme which contains atoms of oxygen and of the metal manganese is encased in diarylphosphinate ligands. When a ligand is released due to a beam of light, the catalyst carries out water hydrolysis.[3]

In polymer chemistry, hydrolysis of polymers can occur during high-temperature processing such as injection moulding leading to chain degradation and loss of product integrity. Polymers most at risk include PET, polycarbonate, nylon and other polymers made by step-growth polymerization. Such materials must be dried prior to moulding.

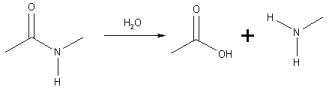

Hydrolysis of amide links

In the hydrolysis of an amide link into a carboxylic acid and an amine or ammonia, the carboxylic acid has a hydroxyl group derived from a water molecule and the amine (or ammonia) gains the hydrogen ion.

A specific case of the hydrolysis of an amide link is the hydrolysis of peptides to smaller fragments or amino acids.

Many polyamide polymers such as nylon 6,6 are attacked and hydrolysed in the presence of strong acids. Such attack leads to depolymerization and nylon products fail by fracturing when exposed to even small amounts of acid. Other polymers made by step-growth polymerization are susceptible to similar polymer degradation reactions. The problem is known as stress corrosion cracking.

Hydrolysis of polysaccharides

In polysaccharides, monosaccharide molecules are linked together by a glycosidic bond. This bond can be cleaved by hydrolysis to yield monosaccharides. The best known disaccharide is sucrose (table sugar). Hydrolysis of sucrose yields glucose and fructose. There are many enzymes which speed up the hydrolysis of polysaccharides. Invertase is used industrially to hydrolyze sucrose to so-called invert sugar. Invertase is an example of a glycoside hydrolase (glucosidase). Lactase is essential for digestive hydrolysis of lactose in milk. Deficiency of the enzyme in humans causes lactose intolerance. β-amylase catalyzes the conversion of starch to maltose. Malt made from barley is used as a source of β-amylase to break down starch into a form that can be used by yeast to produce beer. The hydrolysis of cellulose into glucose, known as saccharification, is catalyzed by cellulase. Animals such as cows (ruminants) are able to digest cellulose because of the presence of symbiotic bacteria which produce cellulases.

Irreversibility of hydrolysis under physiological conditions

Under physiological conditions (i.e. in dilute aqueous solution), a hydrolytic cleavage reaction, where the concentration of a metabolic precursor is low (on the order of 10-3 to 10-6 molar), is essentially thermodynamically irreversible. To give an example:

- A + H2O → X + Y

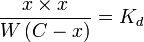

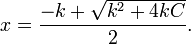

Assuming that x is the final concentration of products, and that C is the initial concentration of A, and W = [H2O] = 55.5 molar, then x can be calculated with the equation:

let Kd×W = k:

then

For a value of C = 0.001 molar, and k = 1 molar, x/C > 0.999. Less than 0.1% of the original reactant would be present once the reaction is complete.

This theme of physiological irreversibility of hydrolysis is used consistently in metabolic pathways, since many biological processes are driven by the cleavage of anhydrous pyrophosphate bonds.

Hydrolysis of metal aqua ions

Metal ions are Lewis acids, and in aqueous solution they form aqua ions, of the general formula M(H2O)nm+. [4] [5] The aqua ions are hydrolyzed, to a greater or lesser extent. The first hydrolysis step is given generically as

- M(H2O)nm+ + H2O ⇌ M(H2O)n-1(OH)(m-1)+ + H3O+

Thus the aqua ion is behaving as an acid in terms of Brønsted-Lowry acid-base theory. This is easily explained by considering the inductive effect of the positively charged metal ion, which weakens the O-H bond of an attached water molecule, making the liberation of a proton relatively easy.

The dissociation constant, pKa, for this reaction is more or less linearly related to the charge-to-size ratio of the metal ion.[6] Ions with low charges, such as Na+ are very weak acids with almost imperceptible hydrolysis. Large divalent ions such as Ca2+, Zn2+, Sn2+ and Pb2+ have a pKa of 6 or more and would not normally be classed as acids, but small divalent ions such as Be2+ are extensively hydrolyzed. Trivalent ions like Al3+ and Fe3+ are weak acids whose pKa is comparable to that of acetic acid. Solutions of salts such as BeCl2 or Al(NO3)3 in water are noticeably acidic; the hydrolysis can be suppressed by adding an acid such as nitric acid, making the solution more acidic.

Hydrolysis may proceed beyond the first step, often with the formation of polynuclear species. [6] Some "exotic" species such as Sn3(OH)42+ [7] are well characterized. Hydrolysis tends to increase as pH rises leading, in many cases, to the precipitation of an hydroxide such as Al(OH)3 or AlO(OH). These substances, the major constituents of bauxite, are known as laterites and are formed by leaching from rocks of most of the ions other than aluminium and iron and subsequent hydrolysis of the remaining aluminium and iron.

Ions with a formal charge of four are extensively hydrolyzed and salts of Zr4+, for example, can only be obtained from strongly acidic solutions. With oxidation states five and higher the concentration of the aqua ion in solution is negligible. In effect the aqua ion is a strong acid. For example, aqueous solutions of Cr(VI) contain CrO42-.

- Cr(H2O)6+ → CrO42- + 2 H2O + 8 H+

Note that reactions such as

- 2 CrO42- + H2O ⇌ Cr2O72- + 2 OH-

are formally hydrolysis reactions as water molecules are split up yielding hydroxide ions. Such reactions are common among polyoxometalates.

See also

- Adenosine triphosphate

- Dehydration synthesis

- Polymer degradation

- Solvolysis

References

- ↑ Compendium of Chemical Terminology, hydrolysis, accessed 2007-01-23.

- ↑ Compendium of Chemical Terminology, solvolysis, accessed 2007-01-23.

- ↑ Chemical & Engineering News Vol. 86 No. 35, 1 Sept. 2008, "Manganese Photocatalyst splits water", p. 44

- ↑ Burgess, J. Metal ions in solution, (1978) Ellis Horwood, New York

- ↑ Richens, D. T. (1997). The chemistry of aqua ions : synthesis, structure, and reactivity : a tour through the periodic table of the elements. Wiley. ISBN 0471970581.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Baes, C.F.; Mesmer, R.E. The Hydrolysis of Cations, (1976),Wiley, New York

- ↑ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, A. (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd Edition ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-7506-3365-4. p384

![K_d = \frac{\left[X\right] \left[Y\right]} {\left[H_2O\right] \left[A\right]}](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/6ccd56df6f5944a5d37e9740ddcede3e.png)