International humanitarian law

International humanitarian law (IHL), often referred to as the laws of war, the laws and customs of war or the law of armed conflict, is the legal corpus "comprised of the Geneva Conventions and the Hague Conventions, as well as subsequent treaties, case law, and customary international law."[1] It defines the conduct and responsibilities of belligerent nations, neutral nations and individuals engaged in warfare, in relation to each other and to protected persons, usually meaning civilians.

The law is mandatory for nations bound by the appropriate treaties. There are also other customary unwritten rules of war, many of which were explored at the Nuremberg War Trials. By extension, they also define both the permissive rights of these powers as well as prohibitions on their conduct when dealing with irregular forces and non-signatories.

Two Historical Streams: The Law of Geneva and The Law of The Hague

Modern International Humanitarian Law is made up of two historical streams: the law of The Hague referred to in the past as the law of war proper and the law of Geneva or humanitarian law. [2] The two streams take their names from a number of international conferences which drew up treaties relating to war and conflict, in particular the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, and the Geneva Conventions, the first which was drawn up in 1863. Both are branches of jus in bello, international law regarding acceptable practices while engaged in war and armed conflict.

The Law of The Hague or the Laws of War proper,"determines the rights and duties of belligerents in the conduct of operations and limits the choice of means in doing harm." [3] In particular, it concerns itself with the definition of combatants, establishes rules relating to the means and methods of warfare, and examines the issue of military objectives. [4]

Systematic attempts to limit the savagery of warfare only began to develop in the 19th century. Such concerns were able to build on the changing view of warfare by states influenced by the Age of Enlightenment. The purpose of warfare was to overcome the enemy state and this was obtainable by disabling the enemy combatants. Thus, "(t)he distinction between combatants and civilians, the requirement that wounded and captured enemy combatants must be treated humanely, and that quarter must be given, some of the pillars of modern humanitarian law, all follow from this principle."[5]

The Law of Geneva

Although the term “humanitarian law” did not come into use until after WWII, humanitarian efforts to protect the victims of armed conflicts, i.e. the wounded, the sick and the shipwrecked have antecedents dating back to ancient times.[6] Even though early Old Testament accounts describe massacres of civilian populations, i.e. the massacre of Midianites, later in the history of the people of Israel there appears a more humanitarian approach, i.e. there is a record of the King of Israel preventing the slaying of the captured enemy. In ancient India there are records, for example the Laws of Manu, proscribing the types of weapons that should not be used and the command not to kill the enemy "who folds his hands in supplication." In ancient China we find references to the need to protect civilians: "Customary rules in Ancient China ... attach great importance to the protection of civilians, as the aim of war is to defeat those persons responsible for the war, not the innocent civilians." While according to Muslim law, Islamic jurists have held that a prisoner should not be killed as he "cannot be held responsible for mere acts of belligerency." [7]

However, it wasn't until second half of the 18th century that more systematic efforts were made to try prevent the suffering of war victims. Such activity was inspired by the involvement of a number of individuals such as Florence Nightingale during the Crimean War and Henry Dunant a Genevese businessman who had worked with wounded soldiers at the Battle of Solferino. He wrote a book, A Memory of Solferino, which described the horrors he had witnessed. His reports led to the founding of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in 1863 and the convening of a conference in Geneva in 1864 which drew up the Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field.[8]

The Law of Geneva, was directly inspired by the principle of humanity. It relates to those who are not participating in the conflict as well as military personnel hors de combat. It provides the legal basis for protection and humanitarian assistance carried out by impartial humanitarian organizations such as the ICRC.[9] This focus can be found in the Geneva Conventions.

Geneva Conventions

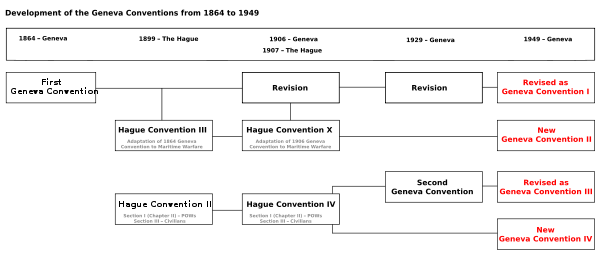

The Geneva Conventions are the result of a process that developed in a number of stages between 1864 and 1949 which focused on the protection of civilians and those who can no longer fight in an armed conflict. As a result of World War II, all four conventions were revised based on previous revisions and partly on some of the 1907 Hague Conventions and readopted by the international community in 1949. Later conferences have added provisions prohibiting certain methods of warfare and addressing issues of civil wars.

The Geneva Conventions are:

- First Geneva Convention "for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field" (first adopted in 1864, last revision in 1949)

- Second Geneva Convention "for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea" (first adopted in 1949, successor of the 1907 Hague Convention X)

- Third Geneva Convention "relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War" (first adopted in 1929, last revision in 1949)

- Fourth Geneva Convention "relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War" (first adopted in 1949, based on parts of the 1907 Hague Convention IV)

In addition, there are three additional amendment protocols to the Geneva Convention:

- Protocol I (1977): Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts. As of 12 January 2007 it had been ratified by 167 countries.

- Protocol II (1977): Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts. As of 12 January 2007 it had been ratified by 163 countries.

- Protocol III (2005): Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Adoption of an Additional Distinctive Emblem. As of June 2007 it had been ratified by 17 countries and signed but not yet ratified by an additional 68 countries.

While the Geneva Conventions of 1949 can be seen as the result of a process which began in 1864, today, they have "achieved universal participation with 194 parties." This means that they apply to almost any international armed conflict.[10]

Historical Convergence between IHL and the Laws of War

With the adoption of the 1977 Protocols to the Geneva Conventions, the two strains of law began to converge. Already before, articles focusing on humanity could be found in the Law of The Hague (i.e. the protection of certain prisoners of war and civilians in occupied territories) articles which were later incorporated into the Law of Geneva in 1929 and 1949). However the Protocols of 1977 relating to the protection of victims in both international and internal conflict not only incorporated aspects of both the Law of The Hague and the Law of Geneva, but also important human rights aspects. [11]

Basic rules of IHL

- Persons hors de combat and those not taking part in hostilities shall be protected and treated humanely.

- It is forbidden to kill or injure an enemy who surrenders or who is hors de combat.

- The wounded and sick shall be cared for and protected by the party to the conflict which has them in its power. The emblem of the red cross or the red crescent must be respected as the sign of protection.

- Captured combatants and civilians must be protected against acts of violence and reprisals. They shall have the right to correspond with their families and to receive relief.

- No one shall be subjected to torture, corporal punishment or cruel or degrading treatment.

- Parties to a conflict and members of their armed forces do not have an unlimited choice of methods and means of warfare.

- Parties to a conflict shall at all times distinguish between the civilian population and combatants. Attacks shall be directed solely against military objectives.[12]

Examples

Well-known examples of such rules include the prohibition on attacking doctors or ambulances displaying a Red Cross. It is also prohibited to fire at a person or vehicle bearing a white flag, since that indicates an intent to surrender or a desire to communicate. In either case, the persons protected by the Red Cross or white flag are expected to maintain neutrality, and may not engage in warlike acts; in fact, engaging in war activities under a white flag or red cross is itself a violation of the laws of war.

These examples of the laws of war address declaration of war, (the UN charter (1945) Art 2, and some other Arts in the charter, curtails the right of member states to declare war; as does the older and toothless Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928 for those nations who ratified it but used against Germany in the Nuremberg War Trials), acceptance of surrender and the treatment of prisoners of war; the avoidance of atrocities; the prohibition on deliberately attacking civilians; and the prohibition of certain inhumane weapons. It is a violation of the laws of war to engage in combat without meeting certain requirements, among them the wearing of a distinctive uniform or other easily identifiable badge and the carrying of weapons openly. Impersonating soldiers of the other side by wearing the enemy's uniform and fighting in that uniform, is forbidden, as is the taking of hostages.

International Committee of the Red Cross

The ICRC is the only institution explicitly named under international humanitarian law (IHL) as a controlling authority. The legal mandate of the ICRC stems from the four Geneva Conventions of 1949, as well as its own Statutes.

| “ | The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is an impartial, neutral, and independent organization whose exclusively humanitarian mission is to to protect the lives and dignity of victims of war and internal violence and to provide them with assistance. | ” |

|

—Mission of ICRC |

||

Violations and punishment

During conflict, punishment for violating the laws of war may consist of a specific, deliberate and limited violation of the laws of war in reprisal.

Soldiers who break specific provisions of the laws of war lose the protections and status afforded as prisoners of war but only after facing a "competent tribunal" (GC III Art 5). At that point they become an unlawful combatant but they must still be "treated with humanity and, in case of trial, shall not be deprived of the rights of fair and regular trial", because they are still covered by GC IV Art 5.

Spies and "terrorists" are only protected by the laws of war if the power which holds them is in a state of armed conflict or war and until they are found to be an unlawful combatant. Depending on the circumstances, they may be subject to civilian law or military tribunal for their acts and in practice have been subjected to torture and/or execution. The laws of war neither approve nor condemn such acts, which fall outside their scope. Countries that have signed the UN Convention Against Torture have committed themselves not to use torture on anyone for any reason.

After a conflict has ended, persons who have committed any breach of the laws of war, and especially atrocities, may be held individually accountable for war crimes through process of law.

See also

- Customary international law

- Human Rights

- International law

- Just war

- Law of land warfare

- Protective sign

- Total war

Notes

- ↑ ICRC What is international humanitarian law?

- ↑ Pictet, Jean (1975). Humanitarian law and the protection of war victims. Leyden: Sijthoff. ISBN 90-286-0305-0. pp. 16-17

- ↑ Pictet, Jean (1985). Development and Principles of International Law. Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhoff. ISBN 9024731992. p.2

- ↑ Kalshoven, Frits and Liesbeth Zegveld (March 2001). Constraints on the waging of war: An introduction to international humanitarian law. Geneva: ICRC. p.40

- ↑ Christopher Greenwood in: Fleck, Dieter, ed. (2008). The Handbook of Humanitarian Law in Armed Conflicts. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 0-19-923250-4.p. 20.

- ↑ Bernhardt, Rudolf (1992). Encyclopedia of public international law. Amsterdam: North-Holland. ISBN 0-444-86245-5., Volume 2, pp. 933-936

- ↑ McCoubrey, Hilaire (1999). International Humanitarian Law. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 1840140127. pp. 8-13

- ↑ Christopher Greenwood in: Fleck, Dieter, ed. (2008). The Handbook of Humanitarian Law in Armed Conflicts. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 0-19-923250-4.p. 22.

- ↑ Pictet (1985) p.2.

- ↑ Christopher Greenwood in: Fleck, Dieter, ed. (2008). The Handbook of Humanitarian Law in Armed Conflicts. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 0-19-923250-4.pp. 27-28.

- ↑ Kalshoven+Zegveld (2001) p. 34.

- ↑ de Preux (1988). Basic rules of the Geneva Conventions and their Additional Protocols, 2nd edition. Geneva: ICRC. pp. 1.

References

Carey, John; Dunlap, William (2003). International Humanitarian Law: Origins (International Humanitarian Law) (International Humanitarian Law). Dobbs Ferry, N.Y: Transnational Pub. ISBN 1-57105-264-X.

Gardam, Judith Gail (1999). Humanitarian Law (The Library of Essays in International Law). Ashgate Pub Ltd. ISBN 1-84014-400-9.

Fleck, Dieter (2008). The Handbook of Humanitarian Law in Armed Conflicts. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 0-19-923250-4.

Forsythe, David P. (2005). The humanitarians: the International Committee of the Red Cross. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-84828-8.

McCoubrey, Hilaire (1999). International Humanitarian Law. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 1840140127.

Pictet, Jean (1975). Humanitarian law and the protection of war victims. Leyden: Sijthoff. ISBN 90-286-0305-0.

Pictet, Jean (1985). Development and Principles of International Humanitarian Law. Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhoff. ISBN 9024731992.

UNESCO Staff (1997). International Dimensions of Humanitarian Law. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 92-3-102371-3.

External links

- International humanitarian law- International Committee of the Red Cross website

- International humanitarian law database- Treaties and States Parties

- UN Charter

- Frits Kalshoven and Liesbeth Zegveld, An Introduction to International Humanitarian Law, ICRC, 2001 - Full Text provided by the eLibrary Project (eLib)

- International Legal Search Engine provides easy tri-lingual access to the international rules binding a specific country in the field of international human rights and humanitarian law.

- A Brief History Of The Laws Of War

- The Yearbook of International Humanitarian Law and a free Documentation Database of primary source materials.

- Crimes, Trials and Laws

- International Humanitarian Law Research Initiative

- Survivor bashing - bias motivated hate crimes

- Bibliography of International Humanitarian Law by Ingrid Kost and Hans Thyssen

- Armed Conflict & the Law

- Human Rights in the US and the International Community - Humanitarian Law

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||