Hooke's law

| Continuum mechanics | ||||||||

|

||||||||

Navier–Stokes equations

|

||||||||

In mechanics, and physics, Hooke's law of elasticity is an approximation that states that the amount by which a material body is deformed (the strain) is linearly related to the force causing the deformation (the stress). Materials for which Hooke's law is a useful approximation are known as linear-elastic or "Hookean" materials.

Hooke's law is named after the 17th century British physicist Robert Hooke. He first stated this law in 1676 as a Latin anagram[1], whose solution he published in 1678 as Ut tensio, sic vis, which means:

| “ | As the extension, so the force. | ” |

For systems that obey Hooke's law, the extension produced is directly proportional to the load:

where:

is the distance that the spring has been stretched or compressed away from the equilibrium position, which is the position where the spring would naturally come to rest (usually in meters),

is the distance that the spring has been stretched or compressed away from the equilibrium position, which is the position where the spring would naturally come to rest (usually in meters), is the restoring force exerted by the material (usually in newtons), and

is the restoring force exerted by the material (usually in newtons), and is the force constant (or spring constant). The constant has units of force per unit length (usually in newtons per meter).

is the force constant (or spring constant). The constant has units of force per unit length (usually in newtons per meter).

When this holds, we say that the behavior is linear. If shown on a graph, the line should show a direct variation. There is a negative sign on the right hand side of the equation because the restoring force always acts in the opposite direction of the x displacement (when a spring is stretched to the left, it pulls back to the right).

Contents |

Elastic materials

Objects that quickly regain their original shape after being deformed by a force, with the molecules or atoms of their material returning to the initial state of stable equilibrium, often obey Hooke's law.

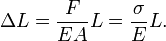

We may view a rod of any elastic material as a linear spring. The rod has length L and cross-sectional area A. Its extension (strain) is linearly proportional to its tensile stress, σ by a constant factor, the inverse of its modulus of elasticity, E, hence,

or

Hooke's law only holds for some materials under certain loading conditions. Steel exhibits linear-elastic behavior in most engineering applications; Hooke's law is valid for it throughout its elastic range (i.e., for stresses below the yield strength). For some other materials, such as aluminium, Hooke's law is only valid for a portion of the elastic range. For these materials a proportional limit stress is defined, below which the errors associated with the linear approximation are negligible.

Rubber is generally regarded as a "non-hookean" material because its elasticity is stress dependent and sensitive to temperature and loading rate.

Applications of the law include spring operated weighing machines, stress analysis and modeling of materials.

The spring equation

1. Ultimate strength

2. Yield strength-corresponds to yield point.

3. Rupture

4. Strain hardening region

5. Necking region.

The most commonly encountered form of Hooke's law is probably the spring equation, which relates the force exerted by a spring to the distance it is stretched by a spring constant, k, measured in force per length.

The negative sign indicates that the force exerted by the spring is in direct opposition to the direction of displacement. It is called a "restoring force", as it tends to restore the system to equilibrium. The potential energy stored in a spring is given by

which comes from adding up the energy it takes to incrementally compress the spring. That is, the integral of force over distance. (Note that potential energy of a spring is always non-negative.)

This potential can be visualized as a parabola on the U-x plane. As the spring is stretched in the positive x-direction, the potential energy increases (the same thing happens as the spring is compressed). The corresponding point on the potential energy curve is higher than that corresponding to the equilibrium position (x = 0). The tendency for the spring is to therefore decrease its potential energy by returning to its equilibrium (unstretched) position, just as a ball rolls downhill to decrease its gravitational potential energy.

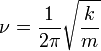

If a mass m is attached to the end of such a spring, the system becomes a harmonic oscillator. It will oscillate with a natural frequency given as either:

radians per second (angular frequency)

radians per second (angular frequency)

or

hertz (cycles per second)

hertz (cycles per second)

where  is frequency (the symbol is the Greek character nu and not the letter v) since

is frequency (the symbol is the Greek character nu and not the letter v) since  .

.

The various lattice spring constants are to be included later.

Multiple springs

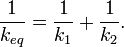

When two springs are attached to a mass and compressed, the following table compares values of the springs.

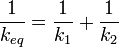

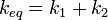

| Comparison | In Series | In Parallel |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Equivalent spring constant |

|

|

| Compressed distance |

|

|

| Energy stored |

|

|

Derivation

-

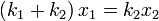

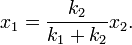

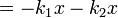

Equivalent Spring Constant (Series) Deriving  in the series case is a little trickier than in the parallel case. Defining the equilibrium position of the block to be x2, we'll be looking for equation for the force on the block that looks like:

in the series case is a little trickier than in the parallel case. Defining the equilibrium position of the block to be x2, we'll be looking for equation for the force on the block that looks like:

To begin, we'll also define the equilibrium position of the point between the two springs to be x1.

The force on the block is

Meanwhile, the force on the point between the two springs is

Now, when the block is pushed so the springs are compressed and the system is allowed to come to equilibrium, the force between the springs must sum to zero, so with

we can solve for

we can solve for  :

:so

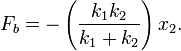

Now we just plug this back into (1):

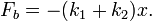

Finally, the force on the block has been found:

So we can define everything in the parenthesis to be

Which can also be written:

-

-

Equivalent Spring Constant (Parallel) Both springs are touching the block in this case, and whatever distance spring 1 is compressed has to be the same amount spring 2 is compressed. The force on the block is then:

So the force on the block is

Which is why we can define the equivalent spring constant as

-

-

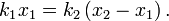

Compressed Distance In the case where two springs are in series, the magnitude of the force of the springs on each other are equal: For spring 1, x1 is the distance from equilibrium length, and for spring 2, x2 - x1 is the distance from its equilibrium length. So we can define

Plug these definitions into the force equation, and we'll get a relationship between the compressed distances for the in series case:

-

-

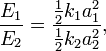

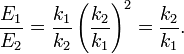

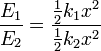

Energy Stored For the series case, the ratio of energy stored in springs is: but a there is a relationship between a1 and a2 derived earlier, so we can plug that in:

For the parallel case,

because the compressed distance of the springs is the same, this simplifies to

-

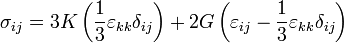

Tensor expression of Hooke's Law

When working with a three-dimensional stress state, a 4th order tensor (cijkl) containing 81 elastic coefficients must be defined to link the stress tensor (σij) and the strain tensor (or Green tensor) (εkl).

Due to the symmetry of the stress tensor, strain tensor, and stiffness tensor, only 21 elastic coefficients are independent.

As stress is measured in units of pressure and strain is dimensionless, the entries of cijkl are also in units of pressure.

Generalization for the case of large deformations is provided by models of neo-Hookean solids and Mooney-Rivlin solids.

Isotropic materials

(see viscosity for an analogous development for viscous fluids.)

Isotropic materials are characterized by properties which are independent of direction in space. Physical equations involving isotropic materials must therefore be independent of the coordinate system chosen to represent them. The strain tensor is a symmetric tensor. Since the trace of any tensor is independent of coordinate system, the most complete coordinate-free decomposition of a symmetric tensor is to represent it as the sum of a constant tensor and a traceless symmetric tensor. (Symon (1971) Ch. 10) Thus:

where  is the Kronecker delta. The first term on the right is the constant tensor, also known as the pressure, and the second term is the traceless symmetric tensor, also known as the shear tensor.

is the Kronecker delta. The first term on the right is the constant tensor, also known as the pressure, and the second term is the traceless symmetric tensor, also known as the shear tensor.

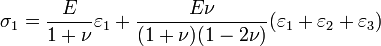

The most general form of Hooke's law for isotropic materials may now be written as a linear combination of these two tensors:

where K is the bulk modulus and G is the shear modulus.

Using the relationships between the elastic moduli, these equations may also be expressed in various other ways. For example, the strain may be expressed in terms of the stress tensor as:

where E is the modulus of elasticity and  is Poisson's ratio. (See 3-D elasticity).

is Poisson's ratio. (See 3-D elasticity).

-

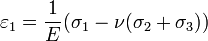

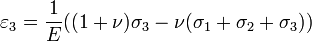

Derivation of Hooke's law in 3D The 3-D form of Hooke's law can be derived using Poisson's ratio and the 1-D form of Hooke's law as follows. Consider the strain and stress relation as a superposition of two effects: stretching in direction of the load (1) and shrinking (caused by the load) in perpendicular directions (2 and 3),

,

, ,

, ,

,

where

is the Poisson's ratio and

is the Poisson's ratio and  the Young Modulus. We get similar equations to the loads in directions 2 and 3,

the Young Modulus. We get similar equations to the loads in directions 2 and 3, ,

, ,

, ,

,

and

,

, ,

, .

.

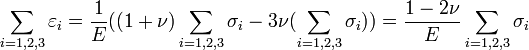

Summing the three cases together (

) we get

) we getor by adding and subtracting one

and further we get by solving

.

.

Calculating the sum

and substituting it to the equation solved for

gives

gives ,

, ,

,

where

and

and  are the Lamé parameters. Similar treatment of directions 2 and 3 gives the Hooke's law in three dimensions.

are the Lamé parameters. Similar treatment of directions 2 and 3 gives the Hooke's law in three dimensions.

Zero-length springs

"Zero-length spring" is the standard term for a spring that exerts zero force when it has zero length. In practice this is done by combining a spring with "negative" length (in which the coils press together when the spring is relaxed) with an extra length of inelastic material. This type of spring was developed in 1932 by Lucien LaCoste for use in a vertical seismograph. A spring with zero length can be attached to a mass on a hinged boom in such a way that the force on the mass is almost exactly balanced by the vertical component of the force from the spring, whatever the position of the boom. This creates a pendulum with very long period. Long-period pendulums enable seismometers to sense the slowest waves from earthquakes. The LaCoste suspension with zero-length springs is also used in gravimeters because it is very sensitive to changes in gravity. Springs for closing doors are often made to have roughly zero length so that they will exert force even when the door is almost closed, so it will close firmly.

See also

- Elastic limit

- Elastic potential energy

- List of scientific laws named after people

- Solid mechanics

References

- ↑ The anagram was "ceiiinossssttuu", [1]; cf. the anagram for the Catenary, which appeared in the preceding paragraph.

- A.C. Ugural, S.K. Fenster, Advanced Strength and Applied Elasticity, 4th ed

- Symon, Keith (1971). Mechanics. Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA. ISBN 0-201-07392-7.