Homological algebra

Homological algebra is the branch of mathematics which studies homology in a general algebraic setting. It is a relatively young discipline, whose origins can be traced to investigations in combinatorial topology (a precursor to algebraic topology) and abstract algebra (theory of modules and syzygies) at the end of the 19th century, chiefly by Henri Poincaré and David Hilbert.

The development of homological algebra was closely intertwined with the emergence of category theory. By and large, homological algebra is the study of homological functors and the intricate algebraic structures that they entail. The hidden fabric of mathematics is woven of chain complexes, which manifest themselves through their homology and cohomology. Homological algebra affords the means to extract information contained in these complexes and present it in the form of homological invariants of rings, modules, topological spaces, and other 'tangible' mathematical objects. A powerful tool for doing this is provided by spectral sequences.

From its very origins, homological algebra has played an enormous role in algebraic topology. Its sphere of influence has gradually expanded and presently includes commutative algebra, algebraic geometry, algebraic number theory, representation theory, mathematical physics, operator algebras, complex analysis, and the theory of partial differential equations. K-theory is an independent discipline which draws upon methods of homological algebra, as does noncommutative geometry of Alain Connes.

Contents |

Chain complexes and homology

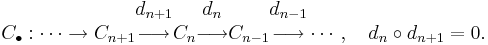

The chain complex is the central notion of homological algebra. It is a sequence  of abelian groups and group homomorphisms, with the property that the composition of any two consecutive maps is zero:

of abelian groups and group homomorphisms, with the property that the composition of any two consecutive maps is zero:

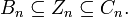

The elements of Cn are called n-chains and the homomorphisms dn are called the boundary maps or differentials. The chain groups Cn may be endowed with extra structure; for example, they may be vector spaces or modules over a fixed ring R. The differentials must preserve the extra structure if it exists; for example, they must be linear maps or homomorphisms of R-modules. For notational convenience, restrict attention to abelian groups (more correctly, to the category Ab of abelian groups); a celebrated theorem by Barry Mitchell implies the results will generalize to any abelian category. Every chain complex defines two further sequences of abelian groups, the cycles Zn = Ker dn and the boundaries Bn = Im dn+1, where Ker d and Im d denote the kernel and the image of d. Since the composition of two consecutive boundary maps is zero, these groups are embedded into each other as

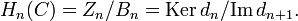

Subgroups of abelian groups are automatically normal; therefore we can define the nth homology group Hn(C) as the factor group of the n-cycles by the n-boundaries,

A chain complex is called acyclic or an exact sequence if all its homology groups are zero.

Chain complexes arise in abundance in algebra and algebraic topology. For example, if X is a topological space then the singular chains Cn(X) are formal linear combinations of continuous maps from the standard n-simplex into X; if K is a simplicial complex then the simplicial chains Cn(K) are formal linear combinations of the n-simplices of X; if A = F/R is a presentation of an abelian group A by generators and relations, where F is a free abelian group spanned by the generators and R is the subgroup of relations, then letting C1(A) = R, C0(A) = F, and Cn(A) = 0 for all other n defines a sequence of abelian groups. In all these cases, there are natural differentials dn making Cn into a chain complex, whose homology reflects the structure of the topological space X, the simplicial complex K, or the abelian group A. In the case of topological spaces, we arrive at the notion of singular homology, which plays a fundamental role in investigating the properties of such spaces, for example, manifolds.

On a philosophical level, homological algebra teaches us that certain chain complexes associated with algebraic or geometric objects (topological spaces, simplicial complexes, R-modules) contain a lot of valuable algebraic information about them, with the homology being only the most readily available part. On a technical level, homological algebra provides the tools for manipulating complexes and extracting this information. Here are two general illustrations.

- Two objects X and Y are connected by a map f between them. Homological algebra studies the relation, induced by the map f, between chain complexes associated to X and Y and their homology. This is generalized to the case of several objects and maps connecting them. Phrased in the language of category theory, homological algebra studies the functorial properties of various constructions of chain complexes and of the homology of these complexes.

- An object X admits multiple descriptions (for example, as a topological space and as a simplicial complex) or the complex

is constructed using some 'presentation' of X, which involves non-canonical choices. It is important to know the effect of change in the description of X on chain complexes associated to X. Typically, the complex and its homology

is constructed using some 'presentation' of X, which involves non-canonical choices. It is important to know the effect of change in the description of X on chain complexes associated to X. Typically, the complex and its homology  are functorial with respect to the presentation; and the homology (although not the complex itself) is actually independent of the presentation chosen, thus it is an invariant of X.

are functorial with respect to the presentation; and the homology (although not the complex itself) is actually independent of the presentation chosen, thus it is an invariant of X.

Functoriality

A continuous map of topological spaces gives rise to a homomorphism between their nth homology groups for all n. This basic fact of algebraic topology finds a natural explanation through certain properties of chain complexes. Since it is very common to study several topological spaces simultaneously, in homological algebra one is led to simultaneous consideration of multiple chain complexes.

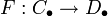

A morphism between two chain complexes,  , is a family of homomorphisms of abelian groups Fn:Cn → Dn that commute with the differentials, in the sense that Fn -1 • dnC = dnD • Fn for all n. A morphism of chain complexes induces a morphism

, is a family of homomorphisms of abelian groups Fn:Cn → Dn that commute with the differentials, in the sense that Fn -1 • dnC = dnD • Fn for all n. A morphism of chain complexes induces a morphism  of their homology groups, consisting of the homomorphisms Hn(F): Hn(C) → Hn(D) for all n. A morphism F is called a quasi-isomorphism if it induces the identity map on the nth homology for all n.

of their homology groups, consisting of the homomorphisms Hn(F): Hn(C) → Hn(D) for all n. A morphism F is called a quasi-isomorphism if it induces the identity map on the nth homology for all n.

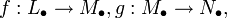

Many constructions of chain complexes arising in algebra and geometry, including singular homology, have the following functoriality property: if two objects X and Y are connected by a map f, then the associated chain complexes are connected by a morphism F = C(f) from  to

to  and moreover, the composition g • f of maps f: X → Y and g: Y → Z induces the morphism C(g • f) from

and moreover, the composition g • f of maps f: X → Y and g: Y → Z induces the morphism C(g • f) from  to

to  that coincides with the composition C(g) • C(f). It follows that the homology groups

that coincides with the composition C(g) • C(f). It follows that the homology groups  are functorial as well, so that morphisms between algebraic or topological objects give rise to compatible maps between their homology.

are functorial as well, so that morphisms between algebraic or topological objects give rise to compatible maps between their homology.

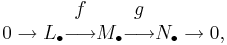

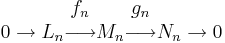

The following definition arises from a typical situation in algebra and topology. A triple consisting of three chain complexes  and two morphisms between them,

and two morphisms between them,  is called an exact triple, or a short exact sequence of complexes, and written as

is called an exact triple, or a short exact sequence of complexes, and written as

if for any n, the sequence

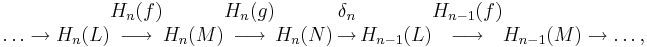

is a short exact sequence of abelian groups. By definition, this means that fn is an injection, gn is a surjection, and Im fn = Ker gn. One of the most basic theorems of homological algebra states that, in this case, there is a long exact sequence in homology,

where the homology groups of L, M, and N cyclically follow each other, and δn are certain homomorphisms determined by f and g, called the connecting homomorphisms. Topological manifestations of this theorem include the Mayer-Vietoris sequence and the long exact sequence for relative homology.

Foundational aspects

Cohomology theories have been defined for many different objects such as topological spaces, sheaves, groups, rings, Lie algebras, and C*-algebras. The study of modern algebraic geometry would be almost unthinkable without sheaf cohomology.

Central to homological algebra is the notion of exact sequence; these can be used to perform actual calculations. A classical tool of homological algebra is that of derived functor; the most basic examples are functors Ext and Tor.

With a diverse set of applications in mind, it was natural to try to put the whole subject on a uniform basis. There were several attempts before the subject settled down. An approximate history can be stated as follows:

- Cartan-Eilenberg: In their 1956 book "Homological Algebra", these authors used projective and injective module resolutions.

- 'Tohoku': The approach in a celebrated paper by Alexander Grothendieck which appeared in the Second Series of the Tohoku Mathematical Journal in 1957, using the abelian category concept (to include sheaves of abelian groups).

- The derived category of Grothendieck and Verdier. Derived categories date back to Verdier's 1967 thesis. They are examples of triangulated categories used in a number of modern theories.

These move from computability to generality.

The computational sledgehammer par excellence is the spectral sequence; these are essential in the Cartan-Eilenberg and Tohoku approaches where they are needed, for instance, to compute the derived functors of a composition of two functors. Spectral sequences are less essential in the derived category approach, but still play a role whenever concrete computations are necessary.

There have been attempts at 'non-commutative' theories which extend first cohomology as torsors (important in Galois cohomology).

References

- Henri Cartan, Samuel Eilenberg, Homological algebra. With an appendix by David A. Buchsbaum. Reprint of the 1956 original. Princeton Landmarks in Mathematics. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 1999. xvi+390 pp. ISBN 0-691-04991-2

- Alexander Grothendieck, Sur quelques points d'algèbre homologique. Tôhoku Math. J. (2) 9, 1957, 119--221

- Saunders Mac Lane, Homology. Reprint of the 1975 edition. Classics in Mathematics. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1995. x+422 pp. ISBN 3-540-58662-8

- Peter Hilton; Stammbach, U. A course in homological algebra. Second edition. Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 4. Springer-Verlag, New York, 1997. xii+364 pp. ISBN 0-387-94823-6

- Gelfand, Sergei I.; Yuri Manin, Methods of homological algebra. Translated from Russian 1988 edition. Second edition. Springer Monographs in Mathematics. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 2003. xx+372 pp. ISBN 3-540-43583-2

- Gelfand, Sergei I.; Yuri Manin, Homological algebra. Translated from the 1989 Russian original by the authors. Reprint of the original English edition from the series Encyclopaedia of Mathematical Sciences (Algebra, V, Encyclopaedia Math. Sci., 38, Springer, Berlin, 1994). Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1999. iv+222 pp. ISBN 3-540-65378-3

- Weibel, Charles A., An introduction to homological algebra. Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics, 38. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994. xiv+450 pp. ISBN 0-521-43500-5; 0-521-55987-1