Hoboken, New Jersey

| Hoboken, New Jersey | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Coordinates: | |

| Country | United States |

|---|---|

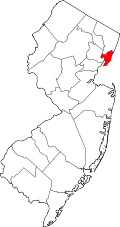

| State | New Jersey |

| County | Hudson |

| Incorporated | April 9, 1849 |

| Government | |

| - Type | Faulkner Act (Mayor-Council) |

| - Mayor | David Roberts |

| Area | |

| - Total | 2.0 sq mi (5.1 km²) |

| - Land | 1.3 sq mi (3.3 km²) |

| - Water | 0.7 sq mi (1.8 km²) |

| Elevation [1] | 30 ft (9 m) |

| Population (2006)[2] | |

| - Total | 39,853 |

| - Density | 30,239.2/sq mi (11,675.4/km²) |

| Time zone | Eastern (EST) (UTC-5) |

| - Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC-4) |

| ZIP code | 07030 |

| Area code(s) | 201, 551 |

| FIPS code | 34-32250[3][4] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0885257[5] |

| Website: http://www.hobokennj.org | |

Hoboken is a city in Hudson County, New Jersey, United States. As of the 2000 United States Census, the city's population was 38,577.

Contents |

Geography

Hoboken lies on the west bank of the Hudson River across from the Manhattan, New York City neighborhoods of the West Village and Chelsea between Weehawken Cove and Union City at the north and Jersey City (the county seat) at the south and west.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 5.1 km² (2.0 mi²). 3.3 km² (1.3 mi²) of it is land and 1.8 km² (0.7 mi²) of it is water. The total area is 35.35% water.

Hoboken has 48 streets laid out in a grid, with numbered streets running east-west. Many north-south streets were named for US presidents (Washington, Adams, Madison, Monroe), though Clinton Street likely honors 19th century politician DeWitt Clinton.

Hoboken's zip code is 07030 and its area code is 201 with 551 overlaid.

Demographics

| Historical populations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 9,662 |

|

|

| 1870 | 20,297 | 110.1% | |

| 1880 | 30,999 | 52.7% | |

| 1890 | 43,648 | 40.8% | |

| 1900 | 59,364 | 36% | |

| 1910 | 70,324 | 18.5% | |

| 1920 | 68,166 | −3.1% | |

| 1930 | 59,261 | −13.1% | |

| 1940 | 50,115 | −15.4% | |

| 1950 | 50,676 | 1.1% | |

| 1960 | 48,441 | −4.4% | |

| 1970 | 45,380 | −6.3% | |

| 1980 | 42,460 | −6.4% | |

| 1990 | 33,397 | −21.3% | |

| 2000 | 38,577 | 15.5% | |

| Est. 2006 | 39,853 | [2] | 3.3% |

| historical data sources:[6][7] | |||

As of the census[3] of 2000, there are 38,577 people. (although recent census figures show the population has grown to about 40,000), 19,418 households, and 6,835 families residing in the city. The population density is 11,636.5/km² (30,239.2/mi²), fourth highest in the nation after neighboring communities of Guttenberg, Union City and West New York.[8] There are 19,915 housing units at an average density of 6,007.2/km² (15,610.7/mi²). The racial makeup of the city is 80.82% White, 4.26% African American, 0.16% Native American, 4.31% Asian, 0.05% Pacific Islander, 7.63% from other races, and 2.78% from two or more races. Furthermore 20.18% of those residents also consider themselves to be Hispanic or Latino.

There are 19,418 households out of which 11.4% have children under the age of 18 living with them, 23.8% are married couples living together, 9.0% have a female householder with no husband present, and 64.8% are non-families. 41.8% of all households are made up of individuals and 8.0% have someone living alone who is 65 years of age or older. The average household size is 1.92 and the average family size is 2.73.

In the city the population is spread out with 10.5% under the age of 18, 15.3% from 18 to 24, 51.7% from 25 to 44, 13.5% from 45 to 64, and 9.0% who are 65 years of age or older. The median age is 30 years. For every 100 females, age 18 and over, there are 103.9 males.

The median income for a household in the city is $62,550, and the median income for a family is $67,500. Males have a median income of $54,870 versus $46,826 for females. The per capita income for the city is $43,195. 11.0% of the population and 10.0% of families are below the poverty line. Out of the total population, 23.6% of those under the age of 18 and 20.7% of those 65 and older are living below the poverty line. Hoboken is a bedroom community in which up to 25% of the population (as of 2008) works in finance or real estate.[9]

Name

The name "Hoboken" was decided upon by Colonel John Stevens when he purchased land, on a part of which the city still sits.

It's believed that the Lenape (later called Delaware Indian) referred to the area as the “land of the tobacco pipe”, most likely to refer to the soapstone collected there to carve tobacco pipes, and used a phrase that became “Hopoghan Hackingh”.[10]

The first Europeans to live there were Dutch/Flemish settlers to New Netherlands, who may have bastardized the Lenape phrase, though there is no known written documentation to confirm it. It also cannot be confirmed that the American Hoboken is named after the Flemish town Hoboken, annexed in 1983 to Antwerp, Belgium,[11] whose name is derived from Middle Dutch Hooghe Buechen or Hoge Beuken, meaning High Beeches or Tall Beeches.[12] The city has also been cited as having been named after the Van Hoboken family of the 17th-century estate in Rotterdam, The Netherlands, where there is still a square dedicated to them. It is not known what the area was called in Jersey Dutch, a Dutch-variant language based on Zeelandic and Flemish, with English and possibly Lenape influences, spoken in northern New Jersey during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Like Weehawken, its neighbor to the north, Communipaw and Harisimus to the south, Hoboken had variations in the folks-tongue of the period. Hoebuck, old Dutch for high bluff and likely referring to Castle Point, was used during the colonial era and later spelled in English as Hobuck,[13] Hobock,[14] and Hoboocken.[15]

Hoboken's unofficial nickname is now the "Mile Square City", but it actually covers an area of two square miles when including the under-water parts in the Hudson River. During the late 19th/early 20th century the population and culture of Hoboken was dominated by German language speakers who sometimes called it "Little Bremen", many of whom are buried in Hoboken Cemetery, North Bergen.

The term "hobo" (i.e., a railroad journeyman) is believed to have stemmed from the groups of hobos traveling by railroad from Hoboken.

History

Early and colonial

Hoboken was originally an island, surrounded by the Hudson River on the east and tidal lands at the foot of the New Jersey Palisades on the west. It was a seasonal campsite in the territory of the Hackensack, a sub-group of Lenni Lenape called Unami, whose totem was the turtle. Later called Delaware Indian, the Lenape are believed to have lived for more than 2800 years on lands around and in-between the Hudson and Delaware Rivers. The first European to lay claim the area was Henry Hudson, an Englishman sailing for the Dutch East India Company, who anchored his ship the Halve Maen (Half Moon) at Weehawken Cove on October 2, 1609. The United New Netherland Company was created to manage this new territory and in June of 1623, New Netherland became a Dutch colony. In 1630, Michael Pauw, a burgemeester (mayor) of Amsterdam and a director of the West India Company, received a land grant as patroon on the condition that he would plant a colony of not fewer than fifty persons within four years on the west bank of what had been named the North River. Three Lenape sold the land that is was to become Hoboken (and part of Jersey City) for 80 fathoms (146 m) of wampum, 20 fathoms (37 m) of cloth, 12 kettles, six guns, two blankets, one double kettle and half a barrel of beer. These transactions, variously dated as July 12, 1630 and November 22, 1630, represent the earliest known conveyance for the area. Pauw (whose Latinized name is Pavonia) neglected to settle the land and he was obliged to sell his holdings back to the Company in 1633. It was later acquired by Hendrick Van Vorst, who leased part of the land to Aert Van Putten, a farmer. In 1643, north of what would be later known as Castle Point, Van Putten built a house and a brewery, North America’s first. In series of Indian and Dutch raids and reprisals, Van Putten was killed and his buildings destroyed, and all residents of Pavonia (as the colony was known) were ordered back to New Amsterdam. Deteriorating relations with the Lenape, its isolation as an island, or relatively long distance from New Amsterdam may have discouraged more settlement. In 1664, the English took possession of New Amsterdam with little or no resistance, and in 1668 they confirmed a previous land patent of by Nicolas Verlett. In 1674-75 the area became part of East Jersey, and he province was divided into four administrative districts, Hoboken becoming part of Bergen County, where it remained until the creation of Hudson on February 22, 1840. English-speaking settlers (some relocating from New England) interspersed with the Dutch, but it remained scarcely populated and agrarian. Eventually, the land came into the possession of William Bayard, who originally supported the revolutionary cause, but became a Loyalist Tory after the fall of New York in 1776 when the city and surrounding areas, including the west bank of the re-named Hudson River, were occupied by the British. At the end of the Revolutionary War, Bayard’s property was confiscated by the Revolutionary Government of New Jersey. In 1784, the land described as "William Bayard's farm at Hoebuck" was bought at auction by Colonel John Stevens for 18,360 pounds sterling.

The 19th century

In the early 1800s, Colonel John Stevens developed the waterfront as a resort for Manhattanites, a lucrative source of income, which he may have used for testing his many mechanical inventions. On October 11, 1811 Stevens' ship the Juliana, began operation as the world's first steam-powered ferry with service between Manhattan and Hoboken. In 1825, he designed and built a steam locomotive capable of hauling several passenger cars at his estate. In 1832, Sybil's Cave opened as an attraction serving spring water, and after 1841 became a legend, when Edgar Allan Poe wrote "The Mystery of Marie Roget" about an event that took place there. (In the late 1880s, when the water was found to be contaminated, it was shut and in the 1930s, filled with concrete.) Before his death in 1838, Stevens founded The Hoboken Land Improvement Company, which during the mid- and late-19th century was managed by his heirs and laid out a regular system of streets, blocks and lots, constructed housing, and developed manufacturing sites. In general, the housing consisted of masonry row houses of three to five stories, some of which survive to the present day, as does the street grid. The advantages of Hoboken as a shipping port and industrial center became apparent.

Hoboken was originally formed as a township on April 9, 1849, from portions of North Bergen Township. As the town grew in population and employment, many of Hoboken's residents saw a need to incorporate as a full-fledged city, and in a referendum held on March 29, 1855, ratified an Act of the New Jersey Legislature signed the previous day, and the City of Hoboken was born.[16][17] In the subsequent election, Cornelius V. Clickener became Hoboken's first mayor. On March 15, 1859, the Township of Weehawken was created from portions of Hoboken and North Bergen Township.[16]

In 1870, based on a bequest from Edwin A. Stevens, Stevens Institute of Technology was founded at Castle Point, site of the Stevens family's former estate. By the late 1800s, great shipping lines were using Hoboken as a terminal port, and the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad (later the Erie Lackawanna Railroad] developed a railroad terminal at the waterfront. It was also during this time that German immigrants, who had been settling in town during most of the century, became the predominant population group in the city, at least partially due to its being a major destination port of the Hamburg America Line. In addition to the primary industry of shipbuilding, Hoboken became home to Keuffel and Esser's three-story factory and in 1884, to Tietjan and Lang Drydock (later Todd Shipyards). Well-known companies that developed a major presence in Hoboken after the turn-of the-century included Maxwell House, Lipton Tea, and Hostess.

Birthplace of baseball

The first officially recorded game of baseball in US history took place in Hoboken in 1846 [18] between Knickerbocker Club and New York Nine at Elysian Fields.

In 1845, the Knickerbocker Club, which had been founded by Alexander Cartwright, began using Elysian Fields to play baseball due to the lack of suitable grounds on Manhattan.[19] Team members included players of the St George's Cricket Club, the brothers Harry and George Wright, and Henry Chadwick, the English-born journalist who coined the term "America's Pastime".

By the 1850s, several Manhattan-based members of the National Association of Base Ball Players were using the grounds as their home field while St George's continued to organize international matches between Canada, England and the United States at the same venue. In 1859, Jack Parr's All England Eleven of professional cricketers played the United States XXII at Hoboken, easily defeating the local competition. Sam Wright and his sons Harry and George Wright played on the defeated United States team-a loss which inadvertently encouraged local players to take up baseball. Henry Chadwick believed that baseball and not cricket should become America's pastime after the game drawing the conclusion that amateur American players did not have the leisure time required to develop cricket skills to the high technical level required of professional players. Harry and George Wright then became two of America's first professional baseball players when Aaron Champion raised funds to found the Cincinnati Red Stockings in 1869.

In 1865 the grounds hosted a championship match between the Mutual Club of New York and the Atlantic Club of Brooklyn that was attended by an estimated 20,000 fans and captured in the Currier & Ives lithograph "The American National Game of Base Ball".

With the construction of two significant baseball parks enclosed by fences in Brooklyn, enabling promoters there to charge admission to games, the prominence of Elysian Fields diminished. In 1868 the leading Manhattan club, Mutual, shifted its home games to the Union Grounds in Brooklyn. In 1880, the founders of the New York Metropolitans and New York Giants finally succeeded in siting a ballpark in Manhattan that became known as the Polo Grounds.

"Heaven, Hell or Hoboken"

When the USA decided to enter World War I the Hamburg-American Line piers in Hoboken (and New Orleans) were taken under eminent domain. Federal control of the port and anti-German sentiment led to part of the city being placed under martial law, and many Germans were forcibly moved to Ellis Island or left the city altogether. Hoboken became the major point of embarkation and more than three million soldiers, known as "doughboys", passed through the city. Their hope for an early return led to General Pershing's slogan, "Heaven, Hell or Hoboken... by Christmas."

Interwar years

Following the war, Italians, mostly stemming from the Adriatic port city of Molfetta, became the city's major ethnic group, with the Irish also having a strong presence. While the city experienced the Depression, jobs in the ships yards and factories were still available, and the "tenements" were full. Middle-European Jews, mostly German-speaking, also made their way to the city and established small businesses. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey was established on April 30, 1921. The Holland Tunnel was completed in 1927 and the Lincoln Tunnel in (1937), allowing for easier vehicular travel between New Jersey and New York City, bypassing the waterfront.

Post-World War II

The war provided a shot in the arm for Hoboken as the many industries located in the city were crucial to the war effort. As men went off to battle, more women were hired in the factories, some (most notably, Todd Shipyards), offering classes and other incentives to them. Though some returning service men took advantage of GI housing bills, many with strong ethnic and familial ties chose to stay in town. During the fifties, the economy was still driven by Todd Shipyards, Maxwell House, Lipton Tea, Hostess and Bethlehem Steel and companies with big plants still not inclined to invest in huge infrastructure elsewhere. Unions were powerful and the pay was good.

By the sixties, though, things began to disintegrate: turn-of-the century housing started to look shabby and feel crowded, shipbuilding was cheaper overseas, and single-story plants surrounded by parking lots made manufacturing and distribution more economical than old brick buildings on congested urban streets. The city appeared to be in the throes of inexorable decline as industries sought (what had been) greener pastures, port operations shifted to larger facilities on Newark Bay, and the car, truck and plane displaced the railroad and ship as the transportation modes of choice in the United States. Many Hobokenites headed to the suburbs, often the close-by ones in Bergen and Passaic Counties, and real-estate values declined. Hoboken sank from its earlier incarnation as a lively port town into a rundown condition and was often included in lists with other New Jersey cities experiencing the same phenomenon, such as Paterson, Elizabeth, Camden, and neighboring Jersey City.

The old economic underpinnings were gone and nothing new seemed to be on the horizon. Attempts were made to stabilize the population by demolishing the so-called slums along River Street and build subsidized middle-income housing at Marineview Plaza, and in midtown, at Church Towers. Heaps of long uncollected garbage and roving packs of semi-wild dogs were not uncommon sights.[20] Though the city had seen better days, Hoboken was never abandoned. New infusions of immigrants, most notably Puerto Ricans, kept the storefronts open with small businesses and housing stock from being abandoned, but there wasn't much work to be had. Washington Street, commonly called "the avenue", was never boarded up, and the tightly-knit neighborhoods remained home to many who were still proud of their city. Stevens stayed a premiere technology school, Maxwell House kept chugging away, and Bethlehem Steel still housed sailors who were dry-docked on its piers. Italian-Americans and other came back to the "old neighborhood" to shop for delicatessen. Some streets were "iffy", but most were not pulled in at night.

On the Waterfront

The waterfront defined Hoboken as an archetypal port town and powered its economy from the mid-19th to mid-20th century, by which time it had become essentially industrial (and mostly inaccessible to the general public). The large production plants of Lipton Tea and Maxwell House, and the drydocks of Bethlehem Steel dominated the northern portion for many years. The southern portion (which had been a US base of the Hamburg-American Line) was seized by the federal government under eminent domain at outbreak of World War I, after which it became (with the rest of the Hudson County) a major East Coast cargo-shipping port. On the Waterfront, consistently listed among the five best American films ever, was shot in Hoboken, dramatically highlighting the rough and tumble lives of longshoremen and the infiltration of unions by organized crime.

With the construction of the interstate highway system and containerization shipping facilities (particularly at Port Newark-Elizabeth Marine Terminal), the docks became obsolete, and by the 1970s were more or less abandoned. A large swathe of River Street, known as the Barbary Coast for its taverns and boarding houses (which had been home for many dockworkers, sailors, merchant marines, and other seamen) was leveled as part of an urban renewal project. Though control of the confiscated area had been returned to the city in the 1950s, complex lease agreements with the Port Authority gave it little influence on its management. In the 1980s, the waterfront dominated Hoboken politics, with various civic groups and the city government engaging in sometimes nasty, sometimes absurd politics and court cases. By the 1990s, agreements were made with the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, various levels of government, Hoboken citizens, and private developers to build commercial and residential buildings and "open spaces" (mostly along the bulkhead and on the foundation of un-utilized Pier A).

The northern portion, which had remained in private hands, has also been re-developed. While most of the dry-dock and production facilities were razed to make way for mid-rise apartment houses, many sold as investment "condos", some buildings were renovated for adaptive re-use (notably the Tea House and the Machine House, home of the Hoboken Historic Museum). Zoning requires that new construction follow the street grid and limits the height of new construction to retain the architectural character of the city and open sight-lines to the river. Downtown, Sinatra Park and Sinatra Drive honor the man most consider to be Hoboken's most famous son, while uptown the name Maxwell recalls the factory with its smell of roasting coffee wafting over town and its huge neon "Good to the Last Drop" sign, so long a part of the landscape. The midtown section is dominated by the serpentine rock outcropping atop of which sits Stevens Institute of Technology (which also owns some, as yet, un-developed land on the river). At the foot of the cliff is Sybil's Cave (where 19th century day-trippers once came to "take the waters" from a natural spring), long sealed shut, though plans for its restoration are in place. The promenade along the river bank is part of the Hudson River Waterfront Walkway, a state-mandated master plan to connect the municipalities from the Bayonne Bridge to George Washington Bridge and provide contiguous unhindered access to the water's edge and to create an urban linear park offering expansive views of the Hudson with the spectacular backdrop of the New York skyline.

Pre- and post-millennium

During the late 1970s and 1980s, the city witnessed a speculation spree, fueled by transplanted New Yorkers and others who bought many turn-of-the-century brownstones in neighborhoods that the still solid middle and working class population had kept intact and by local and out-of-town real-estate investors who bought up late 19th century apartment houses often considered to be tenements. Hoboken experienced a wave of fires, some of which proved to be arson. Applied Housing, a real-estate investment firm, took advantage of US government incentives to renovate "sub-standard" housing and receive subsidized rental payments (commonly know as Section 8), which enabled some low-income, displaced, and disabled residents to move within town. Hoboken attracted artists, musicians, upwardly-mobile commuters (known as yuppies), and "bohemian types" interested in the socio-economic possibilities and challenges of a bankrupt New York and who valued the aesthetics of Hoboken's residential, civic and commercial architecture, its sense of community, and relatively (compared to Lower Manhattan) cheaper rents, and quick, train hop away. Maxwell's (a live music venue and restaurant) opened and Hoboken became a "hip" place to live. Amid this social upheaval, so-called "newcomers" displaced some of the "old-timers" in the eastern half of the city.

This gentrification resembled that of parts of Brooklyn and downtown Jersey City and Manhattan's East Village, (and to a lesser degree, SoHo and TriBeCa, which previously had not been residential). The initial presence of artists and young people changed the perception of the place such that others who would not have considered moving there before perceived it as an interesting, safe, exciting, and eventually, desirable. The process continued as many suburbanites, transplanted Americans, internationals, and immigrants (most focused on opportunities in NY/NJ region and proximity to Manhattan) began to make the "Jersey" side of the Hudson their home, and the "real-estate boom" of the era encouraged many to seek investment opportunities. Empty lots were built on, tenements became condominiums. Hoboken felt the impact of the destruction of the World Trade Center intensely, many of its newer residents having worked there. Re-zoning encouraged new construction on former industrial sites on the waterfront and the traditionally more impoverished low-lying west side of the city where, in concert with Hudson-Bergen Light Rail and New Jersey State land-use policy, transit villages are now being promoted. Hoboken became, and remains, a focal point in American rediscovery of urban living, and is often used as staging ground for those wishing to move to the New York/New Jersey metropolitan region.

Government

Local government

The City of Hoboken is governed under the Faulkner Act (Mayor-Council) system of municipal government by a Mayor and a nine-member City Council. The City Council consists of three members elected at large from the city as a whole, and six members who each represent one of the city's six wards, all of whom are elected to four-year, staggered terms. Candidates run independent of any political party's backing.[21]

The Mayor of the City of Hoboken is David Roberts.[22] Members of the City Council are:[23][24]

- 1st Ward: Theresa Castallano

- 6th Ward: Nino Giacchi (Council President)

- At-Large: Terry LaBruno (Council Vice-President)

- At-Large: Peter Cammarano

- At-Large: Ruben Ramos Jr.

- 2nd Ward: Beth Mason

- 3rd Ward: Michael Russo

- 4th Ward: Dawn Zimmer

- 5th Ward: Peter Cunningham

Mayoral election history

During Hoboken's 150 year history as an incorporated city, the elections that have been held for Mayor of Hoboken and members of the Hoboken city council have been largely operated by Hoboken's community. Hoboken's political landscape has been shaped by a strong connection between City Hall and the citizens of Hoboken. Many of the people running for mayor / councilman were people who grew up in Hoboken.

Among the most recent elections include:

- Thomas Vezzetti vs. Steve Cappiello (1985; Vezzeti won 6,990 to 6,647)

- Patrick Pasculli vs. Joe Della Fave (1988,1989; Pasculli won)

- Anthony Russo vs. Ira Karasick (1993; Russo won 7,023 to 5,623)

- David Roberts vs. Anthony Russo (2001; Roberts won 6,064 to 4,759)

- David Roberts vs. Carol Marsh (2005; Roberts won 5,761 to 4,239. See The 2005 Hoboken election)

Federal, state and county representation

Hoboken is in the Thirteenth Congressional Districts and is part of New Jersey's 33rd Legislative District.[25]

New Jersey's Thirteenth Congressional District, covering portions of Essex, Hudson, Middlesex, and Union Counties, is now represented by Albio Sires (D, West New York), who won a special election held on November 7, 2006 to fill the vacancy the had existed since January 16, 2006. The seat had been represented by Bob Menendez (D), who was appointed to the United States Senate to fill the seat vacated by Governor of New Jersey Jon Corzine. New Jersey is represented in the Senate by Frank Lautenberg (D, Cliffside Park) and Bob Menendez (D, Hoboken).

For the 2008-2009 Legislative Session, the 33rd District of the New Jersey Legislature is represented in the State Senate by Brian P. Stack (D, Union City) and in the Assembly by Ruben J. Ramos (D, Hoboken) and Caridad Rodriguez (D, West New York).[26] The Governor of New Jersey is Jon Corzine (D, Hoboken).[27]

Hudson County's County Executive is Thomas A. DeGise. The executive, together with the Board of Chosen Freeholders in a legislative role, administer all county business. Hudson County's nine Freeholders (as of 2006) are: District 1: Doreen McAndrew DiDomenico; District 2: William O'Dea; District 3: Jeffrey Dublin; District 4: Eliu Rivera; District 5: Maurice Fitzgibbons; District 6: Tilo Rivas; District 7: Gerald Lange Jr.; District 8: Thomas Liggio; and District 9: Albert Cifelli.

Transportation

- Hoboken Terminal, located at the city's southeastern corner, is a national historic landmark originally built in 1907 by the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad and currently undergoing extensive renovation. It is the origination/destination point for several modes of transportation and an important hub within the NY/NJ metropolitan region's public transit system.

Rail

- New Jersey Transit Hoboken Division: Main Line (to Suffern, and in partnership with MTA/Metro-North, express service to Port Jervis), Bergen County Line, and Pascack Valley Line, all via Secaucus Junction (where transfer is possible to Northeast Corridor Line); Montclair-Boonton Line and Morris and Essex Lines (both via Newark Broad Street Station); North Jersey Coast Line (limited service as Waterfront Connection via Newark Penn Station to Long Branch and Bay Head); Raritan Valley Line (limited service via Newark Penn Station);

- Hudson-Bergen Light Rail: along Hoboken's western perimeter at 2nd and 9th Streets, and at Hoboken Terminal, south-bound to downtown Jersey City and Bayonne, and north-bound to the Weehawken waterfront, Bergenline, and Tonnelle Avenues.

- PATH: 24-hour subway service from Hoboken Terminal (HOB) to midtown Manhattan (33rd) (along 6th Ave to Herald Square/Pennsylvania Station), (via downtown Jersey City) to World Trade Center (WTC), and via Journal Square (JSQ) to Newark Penn Station (NWK).

Water

- NY Waterway: ferry service across the Hudson River from Hoboken Terminal and 14th Street to World Financial Center and Pier 11/Wall Street in lower Manhattan, and to West 39th in midtown Manhattan, where free transfer is available to a variety of "loop" buses.

Surface

- Taxi: Flat fare within city limits and negotiated fare for other destinations.

- NJ Transit buses west-bound from Hoboken Terminal along Observer Highway: 64 to Newark, 68, 85, 87, to Jersey City and other Hudson and suburban destinations.[28]

- NJ Transit buses north-bound from Hoboken Terminal along Washington Street: 126 to Port Authority Bus Terminal via Lincoln Tunnel, 22 to Bergenline/North Hudson, 89 to North Bergen, and 23, 22X (rush hour service) to North Bergen via the waterfront and Boulevard East.[28]

- Zipcar: An online based car sharing service pickup is located downtown at the Center Parking Garage on Park Avenue, between Newark Street and Observer Highway.[29]

- Academy Bus: Parkway Express

- Coach USA: (limited service from Washington/Newark Streets) #144 to Staten Island, #5 to Lincoln Harbor or Jersey City

- Hoboken Crosstown Loop: from City Hall through midtown Hoboken

Air

- Newark Liberty Airport (EWR), 12.8 miles (20.6 km) away, is closest airport in New Jersey with scheduled passenger service

- LaGuardia Airport (LGA) is 12.8 miles (20.6 km) away in Flushing, Queens

- John F. Kennedy Airport (JFK) is 19 miles (31 km) away on Jamaica Bay in Queens

- Teterboro Airport, in the Hackensack Meadowlands, serves private and corporate planes

- Essex County Airport, in Caldwell, is a general aviation airport serving the region

Major Roads

- Lincoln Tunnel: north of city line in Weehawken, with eastern terminus in midtown Manhattan and western access road NJ 495

- Holland Tunnel: south of city line in downtown Jersey City with eastern terminus at Canal Street, Manhattan and western access roads I-78 (New Jersey Turnpike extension) and Routes 1&9

- 14th Street Viaduct to Jersey City Heights and North Hudson

- Paterson Plank Road to Jersey City Heights, North Hudson, and Secaucus

Education

Public schools

Hoboken's public schools are operated by Hoboken Public Schools, and serve students in kindergarten through 12th grade. The district is one of 31 Abbott Districts statewide.[30]

Schools in the district (with 2005-06 enrollment data from the National Center for Education Statistics[31]) are three K-5 elementary schools — Calabro Primary School (125 students), Connors Primary School (237) and Wallace Primary School (499) — both Joseph F. Brandt Middle School (233) and A. J. Demarest Middle School (185) for grades 6-8 and Hoboken High School (621) for grades 9-12.

With many non-Hispanic whites attending private schools, the demographics of the public school system are completely different from the community at large. In the 1990s, Hispanic residents were 30% of Hoboken's population, but accounted for 65% of the school district's students, while the 62% of city's non-Hispanic whites represented 20% of district enrollment.[32] By the 2005-06 school year, Hoboken High School's student body was 68% Hispanic, almost 20% Black and 12% non-Hispanic White, while the 2000 Census showed that the community as a whole was 20.2% Hispanic, 4.3% Black and 70.5% non-Hispanic White; Asians represented just short of 5% of Hoboken's population in 2000, but accounted for only 7 of Hoboken High School's 621 students, just over 1.1%.[33][34]

In addition, Hoboken has two charter schools, which are public schools that operate independently of the Hoboken Public Schools under charters granted by the Commissioner of the New Jersey Department of Education. Elysian Charter School serves students in grades K-8 and Hoboken Charter School in grades K-12.[35]

Private schools

The following private schools are located in Hoboken:

- All Saint's Episcopal Day School

- The Hudson School

- Mustard Seed School

- Stevens Cooperative School

- Hoboken Catholic Academy

University

- see Stevens Institute of Technology

Hoboken firsts

- First brewery in the United States, north of Castle Point.

- The zipper, invented at Hoboken's Automatic Hook & Eye Co.

- The site of the first known baseball game between two different teams, at Elysian Fields.

- The first steam-powered ferry, in 1811, with service to Manhattan.

- First demonstration of a steam locomotive in the United States at 56 Newark Street.

- The first departure of an electrified commuter train, in 1931, driven by Thomas A. Edison from Lackawanna Terminal to Dover, New Jersey.

- The home of the accidental invention of soft ice-cream, 726 Washington Street.

- The nation's first automated parking garage at 916 Garden Street.

- The first Blimpie restaurant opened in 1964 at the corner of Seventh and Washington Streets.[36] A free goldfish in a colored bowl of water was given to all customers who purchased a sandwich during the opening week.

- The first centrally air-conditioned public space in the United States, at Hoboken Terminal.[37]

- The first wireless phone system, at Hoboken Terminal.

- The Oreo cookie, first sold in Hoboken.

Notable residents

((B) denotes born)

- Howard Aiken (1900-1973), pioneer in computing.[38] (B)

- Richard Barone, musician; former frontman for Hoboken pop group, The Bongos.[39]

- Tom Bethune (1849-1908), a.k.a. "Blind Tom" (b. Thomas Wiggins), ex-slave, piano prodigy

- The Bongos, Alternative Rock pioneers.[40]

- Bob Borden (born 1969), writer for, and frequent contributor on, the Late Show with David Letterman.[41]

- Joanne Borgella, Miss F.A.T 2005 on Mo'Nique's Fat Chance, plus-sized models signed to Wilhelmina Models, and a contestant on American Idol, Season 7

- Andre Walker Brewster, Major General U.S. Army, recipient Medal of Honor (B)

- Michael Chang (born 1972), professional tennis player (B)[42]

- Irwin Chusid (born 1951), radio personality, author, music producer, historian

- Jon Corzine (born 1947), Governor of New Jersey.[43]

- John J. Eagan (1872-1956), was a United States Representative from New Jersey.[44] (B)

- Luke Faust (born 1936), musician

- Ken Freedman, general manager/program director and air personality at free-form radio station WFMU

- Bill Frisell (born 1951), "avante-garde" musician and composer

- Dorothy Gibson (1889-1946), pioneering silent film actress, Titanic survivor. (B)

- Hetty Green (1834-1916), businesswoman/entrepreneur.[45]

- Chaim Hirschensohn (1857-1935), rabbi and early Zionist leader

- Juliet Huddy (born 1969), Fox News personality

- Mike Jerrick (born 1954), host of the morning television series Fox & Friends

- Alfred Kinsey (1894-1956), famous psychologist who studied sexual behavior. (B)

- Perry Klaussen (born 1969), founder of local news website Hoboken 411 -- "Hoboken's leading web community."

- Willem de Kooning (1904-1997), 20th century painter.[46]

- Alfred L. Kroeber (1876-1960), prominent 20th century anthropologist.(B)

- Artie Lange (born 1967), comedic actor, alum of MADtv and regular on the Howard Stern Show.[47]

- Dorothea Lange (1895-1965), prominent portrait photographer. (B)

- Caroline Leavitt (born 1952), author

- Mark Leyner (born 1956), post-modern author

- G. Gordon Liddy (born 1930), Watergate conspirator and radio talk show host (B)

- Janet Lupo (born 1950), Playboy Playmate for November 1975. (B)

- Billy Mann, Local Character & Culinary Inspiration

- Eli Manning (born 1981), quarterback for the New York Giants.[48][49]

- Joel Mazmanian (born 1981), NY 1 reporter and MTV News reporter

- Natalie Morales (born 1972), NBC News The Today Show.[50]

- Jesse Palmer (born 1978), former professional football player, former star of the TV show The Bachelor.[48]

- Joe Pantoliano (born 1951), actor[41] (B)

- Maria Pepe (born c. 1960), first girl to play Little League baseball. (B)[51]

- Tom Pelphrey (born 1982), won an Emmy for his role on Guiding Light.[52]

- Daniel Pinkwater (born 1941), National Public Radio commentator/author.[53]

- Anna Quindlen (born 1952), columnist, novelist.[54]

- James Rado (born 1932), co-creator of the Broadway Musical Hair.[55]

- Gerome Ragni (1935-1991), co-creator of the Broadway Musical Hair.[55]

- Alex Rodriguez (born 1975), professional baseball player for the New York Yankees.[56][57]

- Robert Charles Sands (1799-1832), American writer[58]

- John Sayles (born 1950), filmmaker and author.[39]

- Steve Shelley (born 1963), drummer for rock band Sonic Youth

- Jeremy Shockey (born 1980), former New York Giants football player

- Charles Schreyvogel (1861-1912), painter of Western subject matter in the days of the disappearing frontier.[59]

- Frank Sinatra (1915-1998), singer and actor.[39] (B)

- Elliott Smith (1969-2003), singer and songwriter

- Alfred Stieglitz [1], leading figure of 19th and early 20th Century American photography. (B)

- Joe Sulaitis (born 1921), running back for the New York Giants of the NFL from 1943 to 1953.[60]

- Jeff Tamarkin (born 1952), music journalist and editor

- Ryan Songalia, boxing journalist/analyst (B)

- Edwin R. V. Wright (1812-1871), represented New Jersey's 5th congressional district from 1865-1867.[61]

- Yo La Tengo, art-rock band

- Pia Zadora (born 1954), singer and actress. (B)[62]

- Tori Piper, Portrayed Poison Ivy, a villain from the "Batman" series

- My Chemical Romance, a punk-rock band, formed in 2001 by front man Gerard Way (2001- )

- Daniel L Di Nallo (born 1959), U S Navy Senior Chief, recipient 4 Navy and Marine Corps Commendation Medals.

Local attractions

Places of Interest

- Stevens Institute of Technology, situated over-looking the Hudson

- Hoboken Terminal, national historic landmark built in 1908

- Marineview Plaza, considered by some to be an eyesore, but a fine example of "urban renewal" architecture

- Weehawken Cove

- Castle Point

- Sybil's Cave, at the foot of the serpentine rock outcropping on the waterfront (no public access)

- Maxwell's, once dubbed New York's best rock club

- Hoboken Free Public Library, with a fine (if dis-organized) collection of photos, maps,artifacts, and changing exhibitions

- Hoboken Historical Museum, with thematic exhibitions changed bi-annually

- Hudson River Waterfront Walkway, along the river's edge

- DeBaun Auditorium, in the "A" House on Stevens Park, presenting theater and dance productions[63]

- Hoboken Green Market, Tuesdays at Hoboken Terminal

Annual events

- Hoboken House Tour (Spring)-an inside view of private spaces of historical, architectural or aesthetic interest

- Hoboken International Film Festival

- Hoboken Studio Tour (Fall)-open house at many studios of artists working in town

- Hoboken Arts and Music Festival (Spring and Fall)-music, arts and crafts on waterfront and Washington Street

- Hoboken (Secret) Garden Tour-(late Spring)

- Saint Patrick's Day Parade (usually the first Saturday of March)

- Hoboken Flip Cup

- Seventh Inning Stretch (Fall)-presentation of newly commissioned base-ball inspired one-act plays by Mile Square Theater Company

- Feast of Saint Anthony

- St Ann's Feast-almost 100 years old

- New Jersey Transit Festival(Fall)-transportation-related exhibitions at Hoboken Terminal, including train excursions

- Movies Under the Stars (Summer)-an outdoor film series

Parks

Four Hoboken parks were originally developed within city street grid laid out in the 19th century:

- Church Square Park, a town square

- Columbus Park, the only Hudson County park in the city

- Elysian Park, the last remnant of Elysian Fields

- Stevens Park

Other parks, developed later, but fitting into the street pattern in the city's southeast:

- Gateway Park, the smallest and most remote of the city's parks

- Jackson Street Park, the most concrete park in town

- Legion Park

- Madison Park, abutting senior housing complex, more plaza than park

The Hudson River Waterfront Walkway is a state-mandated master plan to connect the municipalities from the Bayonne Bridge to the George Washington Bridge creating an 18-mile (29 km)-long urban linear park and provide contiguous unhindered access to the water's edge. By law, any development on the waterfront must provide a public promenade with a minimum width of 30 feet (9.1 m). To date, completed segments in Hoboken and the new parks and renovated piers that abut them are (from south to north):

- the plaza at Hoboken Terminal

- Pier A

- The promenade and bike path from Newark to 5th Streets

- Frank Sinatra Park

- Castle Point Park

- Sinatra Drive to 12th, currently under construction, at former Maxwell House Coffee plant

- 12th to 14th Streets, at former Bethlehem Steel drydocks

- Hoboken North New York Waterway Pier

- 14th Street Pier (formerly Pier 4)

- 14th Street north to southern side of Weehawken Cove, at the former Lipton Tea plant

- other segments of river-front held privately (notably by Stevens Tech) are not required to build a walkway until the land is re-developed.

The Hoboken Parks Initiative is a municipal plan to create more public open spaces in the city using a variety of financing schemes including contributions from and zoning trade-offs with private developers, NJ State Green Acres funds, and other government grants. It is source of controversy with various civic groups and the city government. Among the proposed projects, the only one to that has yet materialized is at Maxwell Place, whose developer is obligated to build a public promenade on the river. Others include:

- Hoboken Island, a 9/11 memorial connected by bridge to Pier A. Hoboken, New Jersey lost 39 of its citizens, making its September 11th death toll the highest in the state of New Jersey and the second highest in the entire United States (after New York City).[64]

- Pier C, which no longer exists, to be-rebuilt and include sand volleyball court and fishing pier

- Stevens Tech Ice Skating Rink: temporary rink at the eastern end of 5th street to become permanent

- 1600 Park Avenue, 2.4 acre (10,000 m²) park with two handball courts, two basketball courts, and two tennis courts

- Hoboken Cove, a 5-acre (20,000 m2) park along Park Ave at the waterfront

- 16th Street Pier, 0.75 acres (3,000 m²) extending into Weehawken Cove, with playground and overlook terrace

- Green Belt Walkway, also known as the Green Circuit, on city's western perimeter north of the projects, including rooftop tennis courts and swimming complex.

- Upper West Side Park, in the northwestern corner of the city adjacent to the Hudson-Bergen Light Rail tracks north of the 14th Street Viaduct, a 4.2 acre (17,000 m²) park with athletic fields

Trivia

On the Street

- Hoboken was once known as the city with "a bar on every corner" and in fact was once listed in the Guinness Book of Records as the city with "Most bars in a square mile".. However, the local newspaper, the Hoboken Reporter, recently investigated and determined that while there may be the most liquor licenses per corner, New Orleans has more bars per corner. There were well over 200 bars in Hoboken in the first half of the 20th century. There are still well over 100 now. Hoboken limits by law the number of liquor licenses to the number of blocks and the limit is usually reached. Additionally, no license can be moved to within 200 feet (61 m) of another bar or 500 feet (150 m) from a church, which makes it nearly impossible to open a new bar (except in newly renovated perimeter regions of the city).

- Hoboken is home to the Macy's Parade Studio, which houses many of the floats for the famous Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade. [2]

Film, Television and Music

- On the Waterfront (1954) directed by Elia Kazan, was filmed in Hoboken. It concerned difficulties in the shipping industry. It won eight Oscars and was nominated four more times in two categories.[65]

- The title characters in the 2004 film Harold and Kumar Go to White Castle hailed from Hoboken. This could possibly be due to director Danny Leiner's own pre-Hollywood life spent here, as his earlier blockbuster film, Dude, Where's My Car?, also included a reference to the city (an alien character swears to banish another alien menace to Hoboken, New Jersey).

- On the animated series Megas XLR, which is set in New Jersey, the city Hoboken is made fun of, such as in the episodes "All I wanted was a Slushie" and "DMV: Department of Megas Violations" respectively.

- A post-apocalyptic Hoboken is the setting of the off-beat computer RPG The Superhero League of Hoboken, by Legend Entertainment.

- The Looney Toons short "8 Ball Bunny", starring Bugs Bunny, features a baby penguin that Bugs brings to Antarctica, only to have the penguin show him that he was supposed to go to Hoboken instead.

- Hoboken High School graduate Siglinda Sanchez became the first Puerto Rican Capitol Page, when in the summer of 1973, she served as House Speaker Carl Albert's personal page. She appeared on What's My Line? and Jeopardy! and was featured on Josie and the Pussycats and In the News.

- Creators of the Broadway Musical Hair James Rado and Jerome Ragne lived in Hoboken at 64 10th Street in 1968 when they wrote the play and its classic songs such as "Aquarius/Let the Sunshine In", "Hair" and "How Can I be Sure" to name a few.

- The Tori Amos track Father Lucifer contains the lyric, "and girl I've got a condo in Hoboken."

- Maxwell's, once dubbed New York's best rock club, was the first venue to bring prominence to The Bongos, who were based in Hoboken, signed to RCA Records and gained national recognition. Springsteen's "Glory Days" video was shot there.[66]

- The now-defunct band, Operation Ivy, whose members went on to form Rancid, penned and recorded the song "Hoboken" about the town.

- Hoboken Public Library has so many Frank Sinatra CDs that they count him as a separate genre.

- The films Lianna by John Sayles was shot in Hoboken in 1983, and the hit comedy films The Hoboken Chicken Cluck Cluck and the sequal The Hoboken Chicken Quack Quack filmed in 1984 and 1986 were both filmed in Hoboken, mainly Washington Street.

- Scottish band Franz Ferdinand named a remake of their song 'Jacqueline' as 'Better in Hoboken'

- The Twilight Zone episode "The Mighty Casey" features a robot named Casey pitching for a team called the Hoboken Zephyrs (apparently modeled on the Brooklyn Dodgers, especially since the Zephyrs are said to have moved to California... just like the Dodgers (did.)[67]

- Hoboken Saturday Night is the name of the 1970s album produced by The Insect Trust, a band based in the city at the time.

- Hoboken was the backdrop of the Chappelle's Show's "The Mad Real World," a parody of MTV's The Real World.

- Coal Chamber's Album Chamber Music was recorded in Hoboken.

- Polycarp (2007) is a film directed by George Lekovic. The movie was filmed in and around Hoboken and the city also serves as the setting for the film. It premiered June 1, 2007 as the opening film of the Hoboken International Film Festival. Through a series of horrific murders, the occult, biblical prophecy and sex clash in a melee of gore and mystery, with psychiatrists, attorneys, homicide detectives, and rock stars all being suspects.

- The Hoboken Chicken Emergency, a children's book about a large chicken in Hoboken, was made into a movie in 1984.[68]

- The final scene of Léon (The Professional), where Natalie Portman's character "Matilda" is seen planting Leon's fern was filmed in Stevens Institute of Technology, located in an area in Hoboken which closely borders the Hudson River.

- Ricki Lake stars in Mrs. Winterbourne as a character named Connie who loses her mother at twelve in Hoboken, New Jersey.

- Find Me Guilty was partially shot in Hoboken, stars Vin Diesel as Giacomo “Fat Jack” DiNorscio, in the true story of New Jersey’s notorious mob family the Lucchesis.

- Hoboken is mentioned in The Vandals' song 'I've Got an Ape Drape'. The songs states "You can go Hoboken and get one too. Then you'll have a mullet like I do."

- A scene in The Basketball Diaries was filmed at Schnackenberg's Luncheonette at 1110 Washington Street.

- Award-winning Australian rock band The Living End recorded their hit 2008 Dew Process album White Noise at Water Music Studios, Hoboken, NJ. Additionally, the city's name is boldly featured across the back cover of the album, garnering Hoboken international coverage, particularly in Australia.

- There is an Operation Ivy (band) song called Hoboken.

- In the 2008 movie Nick and Norah's Infinite Playlist, one of the main characters, Nick, hailed from Hoboken

Computer Games

- Hoboken was a featured city in the popular PC game Mafia which was set in the 1930s.

See also

- Bergen, New Netherland

- Gateway Region

- Gold Coast, New Jersey

- Landmarks of Hoboken, New Jersey

- Hoboken Reporter

- Hoboken Parks Initiative

- Hudson River Waterfront Walkway

- Hoboken Terminal

- Pavonia, New Netherland

- Stevens Institute of Technology

References

- ↑ USGS GNIS: City of Hoboken, Geographic Names Information System, accessed January 4, 2008.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Census data for Hoboken city, United States Census Bureau. Accessed August 14, 2007.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved on 2008-01-31.

- ↑ A Cure for the Common Codes: New Jersey, Missouri Census Data Center. Accessed July 14, 2008.

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey (2007-10-25). Retrieved on 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "New Jersey Resident Population by Municipality: 1930 - 1990". Retrieved on 2007-03-03.

- ↑ Campbell Gibson (June 1998). "Population of the 100 Largest Cities and Other Urban Places in The United States: 1790 TO 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved on 2007-03-06.

- ↑ U.S. Census Bureau, 2000 Census of Population and Housing, Population and Housing Unit Counts PHC-3-1 United States Summary, Washington, DC, 2004, pp. 105 - 159, accessed November 14, 2006.

- ↑ ABC Eyewitness News. September 29, 2008. 6pm EST broadcast.

- ↑ HM-hist "The Abridged History of Hoboken", Hoboken Museum, Accessed 24-Nov-2006.

- ↑ Nederlandse Geschiedenis, 1600 - 1700

- ↑ U.S. Towns and Cities with Dutch Names, Embassy of the Netherlands. Accessed November 24, 2006.

- ↑ Hoboken Reporter Jan 16, 2005

- ↑ http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/map_item.pl

- ↑ http://files.usgwarchives.org/nj/statewide/history/colrec/vol21/v21-01.txt

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "The Story of New Jersey's Civil Boundaries: 1606-1968", John P. Snyder, Bureau of Geology and Topography; Trenton, New Jersey; 1969. p. 148.

- ↑ "How Hoboken became a city," Part I, Part II, Part III, Hoboken Reporter, March 27, April 3, and April 10, 2005.

- ↑ *Sullivan, Dean (1997). Early Innings: A Documentary History of Baseball, 1825-1908. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803292449. OCLC 36258074.

- ↑ Nieves, Evelyn (1996-04-03). "Our Towns;In Hoboken, Dreams of Eclipsing the Cooperstown Baseball Legend", The New York Times. Retrieved on 2007-10-26.

- ↑ Martin, Antoinette. "In the Region/New Jersey; Residences Flower in a Once-Seedy Hoboken Area", The New York Times, August 10, 2003. Accessed October 26, 2007. "The area back from the Hudson River, along streets named for presidents -- Adams, Jackson, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe -- was sketchy, Mr. Geibel said, and marked by old warehouses, boarded-up windows, raw sewage coming out of pipes and packs of wild dogs running in the streets."

- ↑ 2005 New Jersey Legislative District Data Book, Rutgers University Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, April 2005, p. 145.

- ↑ The Honorable Mayor David Roberts, City of Hoboken. Accessed September 4, 2006.

- ↑ The Hoboken Municipal Council, City of Hoboken. Accessed September 4, 2006.

- ↑ New Hoboken Council prez is Theresa Castellano, The Jersey Journal. Accessed July 2, 2007.

- ↑ 2006 New Jersey Citizen's Guide to Government, New Jersey League of Women Voters, p. 58, accessed August 30, 2006.

- ↑ Legislative Roster: 2008-2009 Session, New Jersey Legislature. Accessed June 6, 2008.

- ↑ About the Governor, New Jersey. Accessed June 6, 2008.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Hudson County bus and train service, New Jersey Transit. Accessed June 13, 2007.

- ↑ Zipcar Car Location 77 Park Av/Hoboken NJ. Zipcar. Accessed November 19 2008

- ↑ Abbott Districts, New Jersey Department of Education. Accessed March 31, 2008.

- ↑ Data for the Hoboken Public Schools, National Center for Education Statistics. Accessed June 19, 2008.

- ↑ Nieves, Evelyn. "Hoboken: Having It All, Then Leaving It", The New York Times, July 5, 1994. Accessed August 7, 2008. "Hispanic residents, 30 percent of the population, provide 65 percent of the students. Non-Hispanic whites, 62 percent of the population, account for roughly 20 percent of the schools' enrollment."

- ↑ Data for Hoboken High School, National Center for Education Statistics. Accessed August 7, 2008.

- ↑ Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000, for Hoboken city, New Jersey, 2000 United States Census. Accessed August 7, 2008.

- ↑ "Approved Charter Schools". New Jersey Department of Education. Retrieved on 2008-08-07.

- ↑ Kleinfield, N.R. (1987-12.13). "Trying to Build a Bigger Blimpie", The New York Times. Retrieved on 2008-08-07.

- ↑ La Gorce, Tammy. "Cool Is a State of Mind (and Relief)", The New York Times, May 23, 2004. Accessed April 10, 2008. "Several decades later, the Hoboken Terminal distinguished itself as the nation's first centrally air-conditioned public space."

- ↑ Howard Hathaway Aiken, The History of Computing Project. Accessed June 1, 2007. "Howard Hathaway Aiken was born March 8, 1900 in Hoboken, New Jersey."

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 Narvaez, Alfonso A. "Hoboken", The New York Times, August 1, 1982. Accessed June 1, 2007. "Old-time residents boast of having had Frank Sinatra among their neighbors, while newcomers point to John Sayles, the writer and movie director; Glenn Morrow, the singer, and Richard Barone, principal songwriter for the musical group The Bongos."

- ↑ Holden, Stephen. "THE HOBOKEN BONGOS WITTY AT BOTTOM LINE", The New York Times, June 26, 1982. Accessed July 7, 2007. "The Bongos, a Hoboken-based pop group that appeared Wednesday at the Bottom Line, are one of the most promising young local bands."

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 This Week's Show Recap, Late Night with David Letterman, September 26, 2003. Accessed July 7, 2007. " Joe is from Hoboken, across the Hudson in New Jersey....Other celebrities who now live in Hoboken, New Jersey: Bob Borden."

- ↑ Vescey, George. "SPORTS OF THE TIMES; One Yank Relaxes on The Fourth", The New York Times, July 5, 1989. Accessed November 2, 2007. "In the British press, Chang will always be the Kid From Hoboken, although the family moved to southern California when Michael was young."

- ↑ Baldwin, Tom. "Corzine's condition upgraded to stable: Spokesman says he won't try to govern from hospital bed", Asbury Park Press, April 24, 2007, accessed April 26, 2007. "It's not clear where Corzine will reside once he is able to leave the hospital — at a rehabilitation center, his Hoboken condominium or Drumthwacket, the governor's mansion in Princeton Township."

- ↑ John Joseph Eagan biography, United States Congress. Accessed July 7, 2007.

- ↑ Rosenblum, Constance. "'Hetty': Scrooge in Hoboken", The New York Times, December 19, 2004. Accessed December 2, 2007. "At the time of her death in 1916, she had amassed a fortune estimated at $100 million, the equivalent of $1.6 billion in current dollars. Through it all she lived in small apartments in Brooklyn Heights and even -- horror of horrors! -- Hoboken."

- ↑ Kimmelman, Michael. "Willem de Kooning Dies at 92; Reshaped U.S. Art", The New York Times, March 20, 1997. Accessed December 2, 2007.

- ↑ Edelstein, Jeff. "Artie Lange Steps up to the plate", New Jersey Monthly, December 2005. Accessed July 18, 2007. "The 38-year-old comedian, a Union native who lives in Hoboken, has been doing daily radio shtick alongside Howard Stern for the past four years."

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Davis; and McGeehan, Patrick. "Corzine's Mix: Bold Ambitions, Rough Edges", The New York Times, November 2, 2005. Accessed January 1, 2008. "But within a year, he had left his wife and the stately New Jersey house in Summit where they had raised their three children. He moved to a Hoboken apartment building that was also home to the Giants quarterbacks Eli Manning and Jesse Palmer, who also starred in the reality series The Bachelor."

- ↑ Eli Manning: I got engaged in Hoboken - Hoboken Now - NJ.com

- ↑ "Having it all: Anchor and Hoboken resident Natalie Morales reflects on motherhood, juggling family and career, and the birth of her son", The Hoboken Reporter, May 8, 2005. Accessed June 1, 2008.

- ↑ "Alumni Profile: Maria Pepe", FDU Magazine, Fall / Winter 1998. Accessed August 20, 2008. ""As a young girl in Hoboken, N.J., in the early 1970s, Pepe often joined the boys’ stick-ball or wiffle-ball games. But when her fellow players decided to sign up for Little League, she thought she might have to sit on the sidelines.... Once she got permission and passed the tryouts, the young pitcher became the first girl to don a Little League uniform."

- ↑ Basford, Mike. "Tom Pelphrey, Actor: Television's Hottest Bad Boy", Rutgers University Alumni Success. Accessed August 20, 2008. "A typical day for Pelphrey begins very early. He commutes to the midtown Manhattan studio everyday from Hoboken, where he shares an apartment with his best friend from Rutgers."

- ↑ "10 Bookends Memoirs, essays personality-filled", San Antonio Express-News, November 10, 1991. Accessed August 20, 2008. "Now we hear more about that old bandit and other loves in "Chicago Days/Hoboken Nights" (Addison-Wesley, $17.95), a collection of stories about Pinkwater's boyhood in Chicago and his early years as an artist in Hoboken."

- ↑ Kurtz, Howard. "Pulitzer-Winner Anna Quindlen to Leave N.Y. Times", Los Angeles Times, September 10, 1994. Accessed August 20, 2008. "But Quindlen, who works out of her Hoboken, N.J., home and prizes her time with her three children, ages 11, 9 and 5, decided the price was too high."

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Cogswell, David. "Hit musical 'Hair' was written in Hoboken", Hudson Reporter, October 2, 2005. Accessed August 20, 2008. "The book and lyrics of Hair were conceived and written on the top floor of a Hoboken apartment building by James Rado and Gerome Ragni, two out-of-work actors."

- ↑ Widdicombe, Ben. "New York Minute: Gallo bails on 'Giallo'", New York Daily News', February 7, 2008. Accessed August 20, 2008. "A-Rod closed a deal on two multimillion-dollar apartments in Hoboken's Hudson Tea complex (which is also home to Giants QB Eli Manning), reports Chaunce Hayden in Steppin' Out magazine."

- ↑ Conley, Kevin. "Perfect Ten: How Peyton's baby brother conquered New York, stuffed Tom Brady, and took over an American football dynasty.", Men's Vogue, September 2008. Accessed August 20, 2008. "While it hardly seems like a big-thumbs-up first-choice destination for a Super Bowl MVP ("I'm going to Hoboken!"), Manning's adopted home, the refuge for indie scenesters like Yo La Tengo, has gone upscale of late.... Manning can now borrow sugar from neighbors like Governor Jon Corzine or Alex Rodriguez."

- ↑ Cyclopaedia of American Literature, accessed via Google Books, p. 273. Accessed August 7, 2008.

- ↑ Hughes, Robert. "How The West Was Spun", Time (magazine), May 13, 1991. Accessed August 14, 2007. "It is of Charles Schreyvogel, a turn-of-the- century Wild West illustrator, painting in the open air. His subject crouches alertly before him: a cowboy pointing a six-gun. They are on the flat roof of an apartment building in Hoboken, N.J."

- ↑ Joe Sulaitis, database Football. Accessed October 1, 2007.

- ↑ Edwin Ruthvin Vincent Wright biography, United States Congress. Accessed June 29, 2007.

- ↑ Strausbaugh, John. "In the Mansion Land of the ‘Fifth Avenoodles’", December 14, 2007. Accessed August 20, 2008. "...and the actress Pia Zadora (born Pia Schipani in Hoboken)."

- ↑ DeBaun Center for Performing Arts. Accessed November 19 2008.

- ↑ Gotham Gazette - Demographics

- ↑ On the Waterfront (1954) - Awards

- ↑ Bruce Springsteen's New Jersey 'The Boss' takes you on a tour of his home state, Hudson Reporter, accessed March 22, 2007.

- ↑ The Twilight Zone: The Mighty Casey, accessed January 31, 2007.

- ↑ The Hoboken Chicken Emergency (1984) (TV)

External links

- City of Hoboken

- Hoboken411.com Popular online community website about Hoboken. Highest ranked with the most daily readers.

- Hobokeni.com Online guide to the mile square since 1995.

- HobokenReporter.com Online version of city's main newspaper.

- Hoboken, New Jersey travel guide from Wikitravel

- realhoboken.com

- Hoboken Public Schools

- Hoboken Public Schools's 2006-07 School Report Card from the New Jersey Department of Education

- Data for the Hoboken Public Schools, National Center for Education Statistics

- USGS satellite image of Hoboken

- Kannekt - an unofficial guide to Hoboken. Reviews are monitored and poor reviews are removed for all of the paid advertisers. BEWARE!!!!

- Hoboken Message Board

- Hoboken Bar Network - Complete Bar Guide for Hoboken, NJ.

- Hoboken Menus - Download Menus from the local Hoboken Restaurants.

- NEW Magazine - Contemporary living magazine and entertainment guide.

- Delivered Vacant, an eight-year chronicle of housing gentrification in Hoboken

- Historic photos of Hoboken and Hamburg America Line ports

- Hoboken, New Jersey is at coordinates

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|