History of the United Kingdom

| History of the British Isles

|

|

By chronology

By country

By topic

|

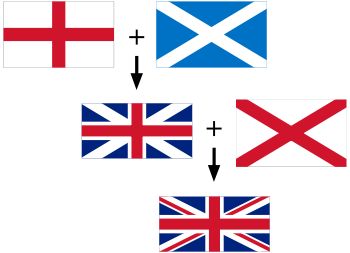

The history of the United Kingdom as an unified sovereign state begins with the political union between the kingdoms of England (which included Wales) and Scotland on 1 May 1707. This event was the result of the Treaty of Union that was agreed on 22 July 1706,[1] and then ratified by both the Parliament of England and Parliament of Scotland each passing an Act of Union. Prior to this, the kingdoms of England and Scotland had been separate states though in personal union since the Union of the Crowns in 1603, when James VI of Scotland succeeded his cousin Elizabeth I as James I of England. The 1707 Union created the Kingdom of Great Britain,[2] which shared a single constitutional monarch and a single parliament at Westminster. On the new kingdom, historian Simon Schama said "What began as a hostile merger would end in a full partnership in the most powerful going concern in the world... it was one of the most astonishing transformations in European history."[3] A further Act of Union in 1800 added the Kingdom of Ireland to create the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

Prior to 1707, the history of the British Isles spans Celtic tribes, Roman invasion with Britain south of the Forth broadly incorporated into the Roman Empire; thereafter invasion by the Anglo-Saxons in the 5th and 6th centuries; invasions by the Vikings in the 9th century, through to the Norman conquest of England in 1066; the development of the separate states of England and Scotland from the 9th century, and competition and cooperation between those states. With Norman control of England and Norman influence in Scotland and Wales, the British Isles faced no further successful military incursion, allowing to develop political, administrative and cultural institutions including representative governance, law systems, and distinguished contributions to the arts and sciences.

The early years of the United Kingdom were marked by Jacobite risings which ended with defeat at Culloden in 1746. Later, victory in the Seven Years' War, in 1763, led to the dominance of the British Empire which was the foremost global power for over a century and grew to become the largest empire in history. By 1921, the British Empire held sway over a population of about 458 million people, approximately one-quarter of the world's population.[4] and as a result, the culture of the United Kingdom, and its industrial, political and linguistic legacy, is widespread.

In 1922, the territory of what is now the Republic of Ireland gained independence, leaving Northern Ireland as a continuing part of the United Kingdom. As a result, in 1927 the United Kingdom changed its formal title to the "United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland",[5] usually shortened to the "United Kingdom", the "UK" or "Britain". Following World War II, in which the UK was an allied power, most of the territories of the British Empire became independent. Many went on to join the Commonwealth of Nations, a free association of independent states.[6] Some have retained the British monarch as their head of state to become independent Commonwealth realms. In its capacity as a great power, and as a leading member of the United Nations, European Union and NATO, the United Kingdom remains a strong economic, cultural, military and political influence in the 21st century.

Contents |

18th century

Birth of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain[7] came into being on 1 May 1707, as a result of the political union of the Kingdom of England (which included Wales) and the Kingdom of Scotland. The terms of the union had been agreed in the Treaty of Union that was negotiated the previous year and then ratified by the parliaments of Scotland and England each approving Acts of Union.[8]

Though previously separate states, England and Scotland had shared monarchs since 1603 when James VI of Scotland become James I of England on the death of the childless Elizabeth I, an event known as the Union of the Crowns. The Treaty of Union enabled the two kingdoms to be combined into a single, united kingdom with the two parliaments merging into a single parliament of Great Britain. Queen Anne, (reigned 1702–14), who had favoured deeper political integration between the two kingdoms, became the first monarch of the united kingdom of Great Britain.

Though now a united kingdom, certain aspects of the former independent kingdoms remained separate in line with the terms in the Treaty of Union. Scottish and English law remained separate, as did the Presbyterian Church of Scotland and the Anglican Church of England, as well as the separate systems of education.

Jacobite risings

The early years of the new united kingdom were marked by major Jacobite Risings, called 'Jacobite Rebellions' by the ruling governments. These Risings were the consequence of James VII of Scotland and II of England being deposed in 1688 with the thrones claimed by his daughter Mary II jointly with her husband, the Dutch born William of Orange. The 'Risings' intensified after the House of Hanover succeeded to the united British Throne in 1714 with the "First Jacobite Rebellion" and "Second Jacobite Rebellion", in 1715 and 1745, known respectively as "The Fifteen" and "The Forty-Five". Although each Jacobite Rising had unique features, they all formed part of a larger series of military campaigns by Jacobites attempting to restore the Stuart kings to the thrones of Scotland and England (and after 1707, the united Kingdom of Great Britain). They ended when the "Forty-Five" rebellion, led by 'the Young Pretender' Charles Edward Stuart was soundly defeated at the Battle of Culloden in 1746.

British Empire

The Seven Years' War, which began in 1756, was the first war waged on a global scale, fought in Europe, India, North America, the Caribbean, the Philippines and coastal Africa. The signing of the Treaty of Paris (1763) had important consequences for Britain and its empire. In North America, France's future as a colonial power there was effectively ended with the ceding of New France to Britain (leaving a sizeable French-speaking population under British control) and Louisiana to Spain. Spain ceded Florida to Britain. In India, the Carnatic War had left France still in control of its enclaves but with military restrictions and an obligation to support British client states, effectively leaving the future of India to Britain. The British victory over France in the Seven Years War therefore left Britain as the world's dominant colonial power.[9]

During the 1760s and 1770s, relations between the Thirteen Colonies and Britain became increasingly strained, primarily because of resentment of the British Parliament's ability to tax American colonists without their consent.[10] Disagreement turned to violence and in 1775 the American Revolutionary War began. The following year, the colonists declared the independence of the United States and with economic and naval assistance from France, would go on to win the war in 1783.

The loss of the United States, at the time Britain's most populous colony, is seen by historians as the event defining the transition between the "first" and "second" empires,[11] in which Britain shifted its attention away from the Americas to Asia, the Pacific and later Africa. Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, had argued that colonies were redundant, and that free trade should replace the old mercantilist policies that had characterised the first period of colonial expansion, dating back to the protectionism of Spain and Portugal. The growth of trade between the newly independent United States and Britain after 1783[12] confirmed Smith's view that political control was not necessary for economic success.

During its first century of operation, the focus of the British East India Company had been trade, not the building of an empire in India. Company interests turned from trade to territory during the 18th century as the Mughal Empire declined in power and the British East India Company struggled with its French counterpart, the La Compagnie française des Indes orientales, during the Carnatic Wars of the 1740s and 1750s. The Battle of Plassey, which saw the British, led by Robert Clive, defeat the French and their Indian allies, left the Company in control of Bengal and a major military and political power in India. In the following decades it gradually increased the size of the territories under its control, either ruling directly or indirectly via local puppet rulers under the threat of force of the Indian Army, 80% of which was composed of native Indian sepoys.

In 1770, James Cook had discovered the eastern coast of Australia whilst on a scientific voyage to the South Pacific. In 1778, Joseph Banks, Cook's botanist on the voyage, presented evidence to the government on the suitability of Botany Bay for the establishment of a penal settlement, and in 1787 the first shipment of convicts set sail, arriving in 1788.

At the threshold to the 19th century, Britain was challenged again by France under Napoleon, in a struggle that, unlike previous wars, represented a contest of ideologies between the two nations.[13] It was not only Britain's position on the world stage that was threatened: Napoleon threatened invasion of Britain itself, and with it, a fate similar to the countries of continental Europe that his armies had overrun.

19th century

- Further information: Georgian era, British Regency, Victorian era, and British Empire

Ireland joins with the Act of Union (1800)

The second stage in the development of the United Kingdom took effect on 1 January 1801, when the Kingdom of Great Britain merged with the Kingdom of Ireland to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

Events that culminated in the union with Ireland had spanned the previous several centuries. Invasions from England by the ruling Normans from 1170 led to centuries of strife in Ireland and successive Kings of England sought both to conquer and pillage Ireland, imposing their rule by force throughout the entire island. In the early 17th century, large-scale settlement by Protestant settlers from both Scotland and England began, especially in the province of Ulster, seeing the displacement of many of the native Roman Catholics Irish inhabitants of this part of Ireland. Since the time of the first Norman invaders from England, Ireland has been subject to control and regulation, firstly by England then latterly by Great Britain.

After the Irish Rebellion of 1641, Irish Roman Catholics were barred from voting or attending the Irish Parliament. The new English Protestant ruling class was known as the Protestant Ascendancy. Towards the end of the 18th century the entirely Protestant Irish Parliament attained a greater degree of independence from the British Parliament than it had previously held. Under the Penal Laws no Irish Catholic could sit in the Parliament of Ireland, even though some 90% of Ireland's population was native Irish Catholic when the first of these bans was introduced in 1691. This ban was followed by others in 1703 and 1709 as part of a comprehensive system disadvantaging the Catholic community, and to a lesser extent Protestant dissenters.[14] In 1798, many members of this dissenter tradition made common cause with Catholics in a rebellion inspired and led by the Society of United Irishmen. It was staged with the aim of creating a fully independent Ireland as a state with a republican constitution. Despite assistance from France the Irish Rebellion of 1798 was put down by British forces.

Possibly influenced by the War of American Independence (1775–1783) , a united force of Irish volunteers used their influence to campaign for greater independence for the Irish Parliament. This was granted in 1782, giving free trade and legislative independence to Ireland. However, the French revolution had encouraged the increasing calls for moderate constitutional reform. The Society of United Irishmen, made up of Presbyterians from Belfast and both Anglicans and Catholics in Dublin, campaigned for an end to British domination. Their leader Theobald Wolfe Tone (1763–98) worked with the Catholic Convention of 1792 which demanded an end to the penal laws. Failing to win the support of the British government, he travelled to Paris, encouraging a number of French naval forces to land in Ireland to help with the planned insurrections. These were slaughtered by government forces, but these rebellions convinced the British under Prime Minister William Pitt that the only solution was to end Irish independence once and for all.

The legislative union of Great Britain and Ireland was completed under the Act of Union 1800, changing the country's name to "United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland". The Act was passed in the British and therefore unrepresentative Irish Parliament with substantial majorities achieved in part (according to contemporary documents) through bribery, namely the awarding of peerages and honours to critics to get their votes.[15] Under the terms of the merger, the separate Parliaments of Great Britain and Ireland were abolished, and replaced by a united Parliament of the United Kingdom. Ireland thus became part of an extended United Kingdom. Ireland sent around 100 MPs to the House of Commons at Westminster and 28 peers to the House of Lords, elected from among their number by the Irish peers themselves (Catholics were not permitted peerage). Part of the trade-off for Irish Catholics was to be the granting of Catholic Emancipation, which had been fiercely resisted by the all-Anglican Irish Parliament. However, this was blocked by King George III who argued that emancipating Roman Catholics would breach his Coronation Oath. The Roman Catholic hierarchy had endorsed the Union. However the decision to block Catholic Emancipation fatally undermined the appeal of the Union.

Napoleonic wars

Hostilities between Great Britain and France recommenced on 18 May 1803. The Coalition war-aims changed over the course of the conflict: a general desire to restore the French monarchy became closely linked to the struggle to stop Bonaparte.

The series of naval and colonial conflicts, including a large number of minor naval actions, resembled those of the French Revolutionary Wars and the preceding centuries of European warfare. Conflicts in the Caribbean, and in particular the seizure of colonial bases and islands throughout the wars, could potentially have some effect upon the European conflict. The Napoleonic conflict had reached the point at which subsequent historians could talk of a "world war". Only the Seven Years' War offered a precedent for widespread conflict on such a scale.

In 1806, Napoleon issued the series of Berlin Decrees, which brought into effect the Continental System. This policy aimed to eliminate the threat of the United Kingdom by closing French-controlled territory to its trade. The United Kingdom's army remained a minimal threat to France; the UK maintained a standing army of just 220,000 at the height of the Napoleonic Wars, whereas France's strength peaked at over 1,500,000 — in addition to the armies of numerous allies and several hundred thousand national guardsmen that Napoleon could draft into the military if necessary. The Royal Navy, however, effectively disrupted France's extra-continental trade — both by seizing and threatening French shipping and by seizing French colonial possessions — but could do nothing about France's trade with the major continental economies and posed little threat to French territory in Europe. In addition France's population and agricultural capacity far outstripped that of the United Kingdom. However, the United Kingdom possessed the greatest industrial capacity in Europe, and its mastery of the seas allowed it to build up considerable economic strength through trade. That sufficed to ensure that France could never consolidate its control over Europe in peace. However, many in the French government believed that cutting the United Kingdom off from the Continent would end its economic influence over Europe and isolate it. Though the French designed the Continental System to achieve this, it never succeeded in its objective.

Victorian era

The Victorian era of the United Kingdom is a term commonly used to refer to the period of Queen Victoria's rule between 1837 and 1901 which signified the height of the British Industrial Revolution and the apex of the British Empire. Although , scholars debate whether the Victorian period—as defined by a variety of sensibilities and political concerns that have come to be associated with the Victorians—actually begins with the passage of Reform Act 1832. The era was preceded by the Regency era and succeeded by the Edwardian period. The latter half of the Victorian era roughly coincided with the first portion of the Belle Époque era of continental Europe and other non-English speaking countries.

Prime Ministers of the period included: William Pitt the Younger, Lord Grenville, Duke of Portland, Spencer Perceval, Lord Liverpool, George Canning, Lord Goderich, Duke of Wellington, Lord Grey, Lord Melbourne, Sir Robert Peel, Lord John Russell, Lord Derby, Lord Aberdeen, Lord Palmerston, Benjamin Disraeli, William Ewart Gladstone, Lord Salisbury, Lord Rosebery

Social history: History of British society

Ireland and the move to Home Rule

Part of the agreement which led to the 1800 Act of Union stipulated that the Penal Laws in Ireland were to be repealed and Catholic Emancipation granted. However King George III blocked emancipation, arguing that to grant it would break his coronation oath to defend the Anglican Church. A campaign under lawyer and politician Daniel O'Connell, and the death of George III, led to the concession of Catholic Emancipation in 1829, allowing Catholics to sit in Parliament. O'Connell then mounted an unsuccessful campaign for the Repeal of the Act of Union.

When potato blight hit the island in 1846, much of the rural population was left without food because cash crops were being exported to pay rents.[16][17] Unfortunately, British politicians such as the Prime Minister Robert Peel were at this time wedded to the economic policy of laissez-faire, which argued against state intervention of any sort. While enormous sums were raised by private individuals and charities (American Indians sent supplies, while Queen Victoria personally gave the present-day equivalent € 70,000) British government inaction (or at least inadequate action) caused the problem to become a catastrophe. The class of cottiers or farm labourers was virtually wiped out in what became known in Britain as 'The Irish Potato Famine' and in Ireland as the Great Hunger.

Most Irish people elected as their MPs Liberals and Conservatives who belonged to the main British political parties (note: the poor didn't have a vote at that time). A significant minority also elected Unionists, who championed the cause of the maintenance of the Act of Union. A former Tory barrister turned nationalist campaigner, Isaac Butt, established a new moderate nationalist movement, the Home Rule League, in the 1870s. After Butt's death the Home Rule Movement, or the Irish Parliamentary Party as it had become known, was turned into a major political force under the guidance of William Shaw and in particular a radical young Protestant landowner, Charles Stewart Parnell. The Irish Parliamentary Party dominated Irish politics, to the exclusion of the previous Liberal, Conservative and Unionist parties that had existed. Parnell's movement proved to be a broad church, from conservative landowners to the Land League which was campaigning for fundamental reform of Irish landholding, where most farms were held on rental from large aristocratic estates.

Parnell's movement campaigned for 'Home Rule', by which they meant that Ireland would govern itself as a region within the United Kingdom, in contrast to O'Connell who wanted complete independence subject to a shared monarch and Crown. Two Home Rule Bills (1886 and 1893) were introduced by Liberal Prime Minister Gladstone, but neither became law, mainly due to opposition from the House of Lords. The issue divided Ireland, for a significant minority (largely though by no means exclusively based in Ulster) , opposed Home Rule, fearing that a Catholic-Nationalist parliament in Dublin would discriminate against them and would also impose tariffs on industry; while most of Ireland was primarily agricultural, six counties in Ulster were the location of heavy industry and would be affected by any tariff barriers imposed.

20th century

- Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom 1900–1945

Marquess of Salisbury | Arthur Balfour | Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman | Herbert Henry Asquith | David Lloyd George | Andrew Bonar Law | Stanley Baldwin | Ramsay MacDonald | Stanley Baldwin | Ramsay MacDonald | Stanley Baldwin | Neville Chamberlain | Winston Churchill

World War I

Partition of Ireland

The 19th and early 20th century saw the rise of Irish Nationalism especially among the Catholic population. Daniel O'Connell led a successful unarmed campaign for Catholic Emancipation. A subsequent campaign for Repeal of the Act of Union failed. Later in the century Charles Stewart Parnell and others campaigned for self government within the Union or "Home Rule".

In 1912, a further Home Rule bill passed the House of Commons but was defeated in the House of Lords, as was the bill of 1893, but by this time the House of Lords had lost its veto on legislation and could only delay the bill by two years - until 1914. During these two years the threat of civil war hung over Ireland with the creation of the Unionist Ulster Volunteers and their nationalist counterparts, the Irish Volunteers. These two groups armed themselves by importing rifles and ammunition and carried out drills openly. The outbreak of World War I in 1914 put the crisis on the political backburner for the duration of the war. The Unionist and Nationalist volunteer forces joined the British army in their thousands and suffered crippling losses in the trenches.

A unilaterally declared "Irish Republic" was proclaimed in Dublin in 1916 during the Easter Rising. The uprising was quelled after six days of fighting and most of its leaders were court-martialled and executed swiftly by British forces. This led to a major increase in support in Ireland for the uprising, and in the declaration of independence was ratified by Dáil Éireann, the self-declared Republic's parliament in 1919. An Anglo-Irish War was fought between Crown forces and the Army of the Irish Republic between January 1919 and June 1921.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, negotiated between teams representing the British and Irish Republic's governments, and ratified by three parliaments,4 established the Irish Free State, which was initially a British Empire Dominion in the same vein as Canada or South Africa, but subsequently left the British Commonwealth and became a republic after World War II, without constitutional ties with the United Kingdom. Six northern, predominantly Protestant, Irish counties (Northern Ireland) have remained part of the United Kingdom.

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland continued in name until 1927 when it was renamed as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland by the Royal and Parliamentary Titles Act 1927. Despite increasing political independence from each other from 1922, and complete political independence since 1949, the union left the two countries intertwined with each other in many respects. Ireland used the Irish Pound from 1928 until 2001 when it was replaced by the Euro. Until it joined the ERM in 1979, the Irish pound was directly linked to the Pound Sterling. Decimalisation of both currencies occurred simultaneously on Decimal Day in 1971. Irish Citizens in the UK have a status almost equivalent to British Citizens. They can vote in all elections and even stand for parliament. British Citizens have similar rights to Irish Citizens in the Republic of Ireland and can vote in all elections apart from presidential elections and referendums. People from Northern Ireland can have dual nationality by applying for an Irish passport in addition to, or instead of a British one.

Northern Ireland was created by the Government of Ireland Act 1920, enacted by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland parliament in 1921. Faced with divergent demands from Irish nationalists and Unionists over the future of the island of Ireland (the former wanted an all-Irish home rule parliament to govern the entire island, the latter no home rule at all) , and the fear of civil war between both groups, the British Government under David Lloyd George passed the Act, creating two home rule Irelands, Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland. Southern Ireland never came into being as a real state and was superseded by the Irish Free State in 1922. That state is now known as the Republic of Ireland.

Having been given self government in 1920 (even though they never sought it, and some like Sir Edward Carson were bitterly opposed) the Northern Ireland government under successive prime ministers from Sir James Craig (later Lord Craigavon) presided over discrimination against the nationalist/ Roman Catholic minority. Northern Ireland became, in the words of Nobel Peace Prize joint-winner, Ulster Unionist Leader and First Minister of Northern Ireland David Trimble, a "cold place for Catholics." Some local council boundaries were gerrymandered, usually to the advantage of Protestants. Voting arrangements for local elections which gave commercial companies votes and minimum income regulations also caused resentment.

Great Depression

The period between the two World Wars was dominated by economic weakness known as the 'Great Depression' or the 'Great Slump'. A short lived post-war boom soon led to a depression that would be felt worldwide. Particularly hardest hit were the north of England and Wales, where unemployment reached 70% in some areas. The General Strike was called during 1926 in support of the miners and their falling wages, but little improved, the downturn continued and the Strike is often seen as the start of the slow decline of the British coal industry. In 1936, 200 unemployed men walked from Jarrow to London in a bid to show the plight of the industrial poor, but the Jarrow March, or the 'Jarrow Crusade' as it was known, had little impact and it would not be until the coming war that industrial prospects improved. George Orwell's book The Road to Wigan Pier gives a bleak overview of the hardships of the time.

World War II and rebuilding

The United Kingdom, along with the British Empire's crown colonies, especially British India, declared war on Nazi Germany in 1939, after the German invasion of Poland. Hostilities with Japan began in 1941, after it attacked British colonies in Asia. The Axis powers were defeated by the Allies in 1945.

The end of the Second World War saw a landslide General Election victory for Clement Atlee and the Labour Party. They were elected on a manifesto of greater social justice with left wing policies such as the creation of a National Health Service, an expansion of the provision of council housing and nationalisation of the major industries. The UK at the time was poor, relying heavily on loans from the United States of America (which were finally paid off in February 2007) to rebuild its damaged infrastructure. Rationing and conscription dragged on into the post war years, and the country suffered one of the worst winters on record. Nevertheless, morale was boosted by events such as the marriage of Princess Elizabeth in 1947 and the Festival of Britain.

As the country headed into the 1950s, rebuilding continued and a number of immigrants from the remaining British Empire were invited to help the rebuilding effort. As the 1950s wore on, the UK had lost its place as a superpower and could no longer maintain its large Empire. This led to decolonization, and a withdrawal from almost all of its colonies by 1970. Events such as the Suez Crisis showed that the UK's status had fallen in the world. The 1950s and 1960s were, however, relatively prosperous times after the Second World War, and saw the beginning of a modernization of the UK, with the construction of its first motorways for example, and also during the 1960s a great cultural movement began which expanded across the world.

Empire to Commonwealth

Britain's control over its Empire loosened during the interwar period. Nationalism became stronger in other parts of the empire, particularly in India and in Egypt.

Between 1867 and 1910, the UK had granted Australia, Canada, and New Zealand "Dominion" status (near complete autonomy within the Empire). They became charter members of the British Commonwealth of Nations (known as the Commonwealth of Nations since 1949) , an informal but closely-knit association that succeeded the British Empire. Beginning with the independence of India and Pakistan in 1947, the remainder of the British Empire was almost completely dismantled. Today, most of Britain's former colonies belong to the Commonwealth, almost all of them as independent members. There are, however, 13 former British colonies — including Bermuda, Gibraltar, the Falkland Islands, and others — which have elected to continue their political links with London and are known as British Overseas Territories.

Although often marked by economic and political nationalism, the Commonwealth offers the United Kingdom a voice in matters concerning many developing countries, and is a forum for those countries to raise concerns. Notable non-members of the Commonwealth are Ireland, the United States and the former middle-eastern colonies and protectorates. In addition, the Commonwealth helps preserve many institutions deriving from British experience and models, such as Westminster-style parliamentary democracy, in those countries.

From The Troubles to the Belfast Agreement

In the 1960s, moderate unionist Prime Minister Terence O'Neill (later Lord O'Neill of the Maine) tried to reform the system, but was met with opposition from extreme Protestant leaders like the Rev. Ian Paisley. The increasing pressures from nationalists for reform and from extreme unionists for No surrender led to the appearance of the civil rights movement under figures like John Hume, Austin Currie and others. Clashes between marchers and the Royal Ulster Constabulary led to increased communal strife. The Army was deployed in 1969 by British Home Secretary James Callaghan to protect nationalists from attack, and was, at first, warmly welcomed. Relationships deteriorated, however, and the emergence of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) , a breakaway from the increasingly Marxist Official IRA, and a campaign of violence by loyalist terror groups like the Ulster Defence Association and others, brought Northern Ireland to the brink of Civil War. The killing by the Army of thirteen unarmed civilians in 1972 in Derry ("Bloody Sunday") inflamed the situation further and turned northern nationalists against the British Army. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, extremists on both sides carried out a series of brutal mass murders, often on innocent civilians. Among the most notorious outrages were the McGurk's Bar bombing and the bombings in Enniskillen and Omagh.

Some British politicians, notably former British Labour minister Tony Benn advocated British withdrawal from Ireland, but this policy was opposed by successive British and Irish governments, who called their prediction of the possible results of British withdrawal the Doomsday Scenario, with widespread communal strife, followed by the mass exodus of hundreds of thousands of men, women and children as refugees to their community's 'side' of the province; nationalists fleeing to western Northern Ireland, unionists fleeing to eastern Northern Ireland. The worst fear was of a civil war which would engulf not just Northern Ireland, but the neighbouring Republic of Ireland and Scotland both of whom had major links with either or both communities. Later, the feared possible impact of British Withdrawal came to be called the Balkanisation of Northern Ireland after the violent break-up of Yugoslavia and the chaos it unleashed.

In the early 1970s, the Parliament of Northern Ireland was prorogued after the province's Unionist Government under the premiership of Brian Faulkner refused to agree to the British Government demand that it hand over the powers of law and order, and Direct Rule was introduced from London starting on 24 March 1972. New systems of governments were tried and failed, including power-sharing under Sunningdale, Rolling Devolution and the Anglo-Irish Agreement. By the 1990s, the failure of the IRA campaign to win mass public support or achieve its aim by British Withdrawal, and in particular the public relations disaster that was the Enniskillen, along with the replacement of the traditional Republican leadership of Ruairí Ó Brádaigh by Gerry Adams, saw a move away from armed conflict to political engagement. These changes were followed the appearance of new leaders in Dublin Albert Reynolds, London John Major and in unionism David Trimble. Contacts initiatively been Adams and John Hume, leader of the Social Democratic and Labour Party, broadened out into all party negotiations, that in 1998 produced the 'Good Friday Agreement' which was approved by a majority of both communities in Northern Ireland and by the people of the Republic of Ireland, where the constitution, Bunreacht na hÉireann was amended to replace a claim it allegedly made to the territory of Northern Ireland with a recognition of Northern Ireland's right to exist, while also acknowledging the nationalist desire for a united Ireland.

Under the Good Friday Agreement, properly known as the Belfast Agreement, a new Northern Ireland Assembly was elected to form a Northern Irish parliament. Every party that reaches a specific level of support is entitled to name a member of its party to government and claim a ministry. Ulster Unionist party leader David Trimble became First Minister of Northern Ireland. The Deputy Leader of the SDLP, Seamus Mallon, became Deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland, though he was subsequently replaced by his party's new leader, Mark Durkan. The Ulster Unionists, Social Democratic and Labour Party, Sinn Féin and Democratic Unionist Party each had ministers by right in the power-sharing assembly. The Assembly and its Executive were later suspended over unionist threats over the alleged delay in the Provisional IRA implementing its agreement to decommission its weaponry, and also the alleged discovery or an IRA spy-ring operating in the heart of the civil service (though this later turned out to be false due to the fact that Denis Donaldson, the person in possession of the incriminating files which pointed to an IRA spy-ring actually worked for the British intelligence).

Growth of modern Britain (late 20th century)

Through the 1970s the UK began integration to the European Economic Community but experienced extreme industrial strife and stagflation following a global economic downturn. As well as this the conflict with the IRA reached its peak in Northern Ireland in a period known as the Troubles. A strict modernization of its economy began under the controversial leader Margaret Thatcher during the 1980s, which saw a time of record unemployment as deindustrialization saw the end of much of the country's manufacturing industries but also a time of economic boom as stock markets became liberated and state owned industries became privatised. However the miners' strike of 1984-1985 saw the end of the UK's coal mining, thanks to the discovery of North Sea gas which brought in substantial oil revenues to aid the new economic boom. This was also the time that the IRA took the issue of Northern Ireland to Great Britain, maintaining a prolonged bombing campaign on the island.

After the economic boom of the 1980s a brief but severe recession occurred between 1991 and 1992 following the economic chaos of Black Wednesday under the John Major government. However the rest of the 1990s saw the beginning of a period of continuous economic growth that has to date lasted over 15 years and was greatly expanded under the New Labour government of Tony Blair following his landslide election victory in 1997.

Devolution for Scotland and Wales

On 11 September 1997, (on the 700th anniversary of the Scottish victory over the English at the Battle of Stirling Bridge), a referendum was held on establishing a devolved Scottish Parliament. This resulted in an overwhelming 'yes' vote both to establishing the parliament and granting it limited tax varying powers. Two weeks later, a referendum in Wales on establishing a Welsh Assembly for was also approved but with a very narrow majority. The first elections were held, and these bodies began to operate, in 1999. The creation of these bodies has widened the differences between the countries of the United Kingdom, especially in areas like healthcare.[18][19] It has also brought to the fore the so-called West Lothian question which is a complaint that devolution for Scotland and Wales but not England has created a situation where all the MPs in the UK parliament can vote on matters affecting England alone but on those same matters Scotland and Wales can make their own decisions.

21st century

In the 2001 General Election, the Labour Party won a second successive victory and the country's economic expansion continued greatly despite the effects of the September 11th attacks in the United States. Following these attacks, the United States began the so-called War on Terror beginning with a conflict in Afghanistan aided by British troops. Despite huge anti-war marches held in London and Glasgow, Blair gave strong support also to the United States invasion of Iraq in 2003. Forty-six thousand British troops, one-third of the total strength of the British Army (land forces), were deployed to assist with the invasion of Iraq and thereafter British armed forces were responsible for security in southern Iraq in the run-up to the Iraqi elections of January 2005.

The Labour Party won the Thursday 5 May 2005 general election and a third consecutive term in office. However the effects of the War on Terror following 9/11 increased the threat of international terrorists plotting attacks against the UK. On Thursday 7 July 2005, a series of four bomb explosions struck London's public transport system during the morning rush-hour. All four incidents were suicide bombings that killed 52 commutors in addition to the 4 bombers.

2007 saw the conclusion of the premiership of Tony Blair, followed by the premiership of Gordon Brown (from 27 June 2007). 2007 also saw an election victory for the pro-independence Scottish National Party (SNP) in the May elections. They formed a minority government with plans to hold a referendum before 2011 to seek a mandate "to negotiate with the Government of the United Kingdom to achieve independence for Scotland."[20] Most opinion polls show minority support for independence, though support varies depending on the nature of the question. The response of the unionist parties has been to call for the establishment of a Commission to examine further devolution of powers,[21] a position that has the support of the Prime Minister.[22]

In the wake of the economic crisis of 2008, the United Kingdom is now in a real threat of entering a possible recession towards the end of 2008 following the collapse of the housing market and rising oil prices which has increased fuel bills in households. It ends 16 years of continuous economic growth.

Social history

Chartism is thought to have originated from the passing of the 1832 Reform Bill, which gave the vote to the majority of the (male) middle classes, but not to the 'working class'. Many people made speeches on the 'betrayal' of the working class and the 'sacrificing' of their 'interests' by the 'misconduct' of the government. In 1838, six members of Parliament and six workingmen formed a committee, which then published the People's Charter.

Victorian attitudes and ideals continued into the first years of the 20th century, and what really changed society was the start of World War I. The army was traditionally never a large employer in the nation, and the regular army stood at 247,432 at the start of the war.[23] By 1918, there were about five million people in the army and the fledgling Royal Air Force, newly formed from the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) and the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) , was about the same size of the pre-war army. The almost three million casualties were known as the "lost generation", and such numbers inevitably left society scarred; but even so, some people felt their sacrifice was little regarded in Britain, with poems like Siegfried Sassoon's Blighters criticising the ill-informed jingoism of the home front.

The social reforms of the last century continued into the 20th with the Labour Party being formed in 1900. Labour did not achieve major success until the 1922 general election. David Lloyd George said after the First World War that "the nation was now in a molten state", and his Housing Act 1919 would lead to affordable council housing which allowed people to move out of Victorian inner-city slums. The slums, though, remained for several more years, with trams being electrified long before many houses. The Representation of the People Act 1918 gave women householders the vote, but it would not be until 1928 that equal suffrage was achieved.

See also

- History of England

- History of Scotland

- Military history of the peoples of the British Isles

- Prehistoric settlement of Great Britain and Ireland

- Economic history of the United Kingdom

- Religion in the United Kingdom

- List of monarchs of the United Kingdom

- List of Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom

Footnotes

¹ The term "United Kingdom" was first used in the 1707 Act of Union. However it is generally seen as a descriptive term, indicating that the kingdoms were freely united rather than through conquest. It is not seen as being actual name of the new United Kingdom, which was the "Kingdom of Great Britain". The "United Kingdom" as a name is taken to refer to the kingdom that emerged when the Kingdom of Great Britain and Kingdom of Ireland merged on 1 January 1801.

² The name "Great Britain" (then spelt "Great Brittaine") was first used by James VI/I in October 1604, who indicated that henceforth he and his successors would be viewed as Kings of Great Britain, not Kings of England and Scotland. However the name was not applied to the state as a unit; both England and Scotland continued to be governed independently. Its validity as a name of the Crown is also questioned, given that monarchs continued using separate ordinals (e.g., James VI/I, James VII/II) in England and Scotland. To avoid confusion, historians generally avoid using the term "King of Great Britain" until 1707 and instead to match the ordinal usage call the monarchs kings or queens of England and Scotland. Separate ordinals were abandoned when the two states merged with the Act of Union 1707, with subsequent monarchs using ordinals apparently based on English not Scottish history (it might be argued that the monarchs have simply taken the higher ordinal, which to date has always been English). One example is Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom, who is referred to as being "the Second" even though there never was an Elizabeth I of Scotland or Great Britain. Thus the term "Great Britain" is generally used from 1707.

³ The number changed several times between 1801 and 1922.

4 The Anglo-Irish Treaty was ratified by (i) The British Parliament (Commons, Lords & Royal Assent) , (ii) Dáil Éireann, and the (iii) the House of Commons of Southern Ireland, a parliament created under the British Government of Ireland Act 1920 which was supposedly the valid parliament of Southern Ireland in British eyes and which had an almost identical membership of the Dáil, but which nevertheless had to assemble separately under the Treaty's provisions to approve the Treaty, the Treaty thus being ratified under both British and Irish constitutional theory.

References

- ↑ "Articles of Union with Scotland 1707". www.parliament.uk. Retrieved on 19October 2008.

- ↑ "THE TREATY or Act of the Union". www.scotshistoryonline.co.uk. Retrieved on 27 August 2008.

- ↑ "Britannia Incorporated". Simon Schama (presenter). A History of Britain. BBC One. 2001-05-22. No. 10. 3 minutes in.

- ↑ Angus Maddison. The World Economy: A Millennial Perspective (p. 98, 242). OECD, Paris, 2001.

- ↑ CIA - The World Factbook - United Kingdom

- ↑ Lloyd, T. O. (1996). The British Empire, 1558-1995. 2nd ed. The short Oxford history of the modern world. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198731337

- ↑ Welcome parliament.uk, accessed 15 November, 2008

- ↑ Ratification:October 1706 - March 1707 parliament.uk, accessed 15 November, 2008

- ↑ Anthony, Pagden (2003). Peoples and Empires: A Short History of European Migration, Exploration, and Conquest, from Greece to the Present. Modern Library. pp. 91.

- ↑ Niall, Ferguson (2004). Empire. Penguin. pp. 73.

- ↑ Anthony, Pagden (1998). The Origins of Empire, The Oxford History of the British Empire. Oxford University Press. pp. 92.

- ↑ James, Lawrence (2001). The Rise and Fall of the British Empire. Abacus. pp. 119.

- ↑ James, Lawrence (2001). The Rise and Fall of the British Empire. Abacus. pp. 152.

- ↑ Laws in Ireland for the Suppression of Popery at University of Minnesota Law School

- ↑ Alan J. Ward, The Irish Constitutional Tradition p.28.

- ↑ Christine Kinealy, This Great Calamity: The Irish Famine 1845-52, Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 1994. ISBN 0-7171-1832-0 p354

- ↑ Cecil Woodham-Smith, The Great Hunger: Ireland 1845–1849 (1962), London, Hamish Hamilton: 31

- ↑ 'Huge contrasts' in devolved NHS BBC News, 28 August 2008

- ↑ NHS now four different systems BBC 2 January 2008

- ↑ Choosing Scotland's Future: A National Conversation: Independence and Responsibility in the Modern World, Annex B Draft Referendum (Scotland) Bill The Scottish Government, Publications

- ↑ MSPs back devolution review body BBC News, 6th December 2007

- ↑ PM backs Scottish powers review BBC News, 17th February 2008

- ↑ The Great War in figures.

Further reading

- Vernon Bogdanor: The British constitution in the twentieth century, (Oxford : Oxford University Press 2005)

- Norman Davies The Isles: A History (Macmillan, 1999)

- Frank Welsh The Four nations: a history of the United Kingdom (Yale, 2003)

- Jeremy Black A history of the British Isles (Macmillan, 1996)

- Hugh Kearney The British Isles: a history of four nations (Cambridge, 1989)

- The Short Oxford History of the British Isles (series)

- G. Williams Wales and the Act of Union (1992)

- S. Ellis & S. Barber (eds) Conquest and Union: Fashioning a British State, 1485–1725 (1995)

- Linda Colley Britons: Forging the Nation, 1707–1837 (New Haven, 1992)

- R.G. Asch (ed) Three Nations: A Common History? England, Scotland, Ireland and British History c.1600–1920 (1993)

- S.J. Connolly (ed) Kingdoms United? Great Britain and Ireland since 1500 (1999)

External links

- Info Britain.co.uk

- History of the United Kingdom: Primary Documents

- http://www.british-history.ac.uk

- Text of 1800 Act of Union

- Act of Union virtual library

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||