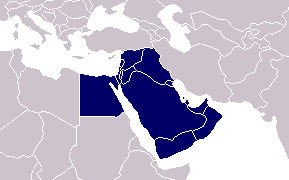

History of the Middle East

- Further information: Timeline of Middle Eastern history

This article is a general overview of the history of the Middle East. For more detailed information, see articles on the histories of individual countries and regions. For discussion of the issues surrounding the definition of the area see the article on Middle East.

Contents |

The Ancient Near East

- See also: Short chronology timeline

Cradle of civilization

The earliest civilizations in history were established in the region now known as the Middle East around 3500 BC, in Mesopotamia (Iraq), widely regarded as the cradle of civilization. The Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians and Assyrians all flourished in this region. Soon after the Sumerian civilization began, the Nile River valley of ancient Egypt was unified under the Pharaohs in the 4th millennium BC, and civilization quickly spread through the Fertile Crescent to the east coast of the Mediterranean Sea and throughout the Levant. The Phoenicians, Israelites and others later built important states in this region.

In the Arabian peninsula (modern day Saudi Arabia) the early Arabs, such as the Nabateans (Arabic: الأنباط) and the Sabaeans (Arabic: السبأيين) appeared around 800 B.C and established powerful and influential civilizations that were the center of trade for centuries, in the heart of the desert.

Persian Empire

From the 6th century BC onwards, several empires dominated the region, beginning with the Persian Empire of the Achaemenids, followed by the Macedonian Empire founded by Alexander the Great, and successor kingdoms such as Ptolemaic Egypt and the Seleucid state in Syria.

The Persian Empire was later revived by the Parthians in the 2nd century BC and continued by the Sassanids from the 2nd century AD. This empire would dominate part of what is now considered the Middle East and continue to influence the rest of the Middle East region until the Islamic conquest of Persia in the 7th century.

Roman Empire

In the 1st century BC, the expanding Roman Republic absorbed the whole Eastern Mediterranean area (which included much of the Near East) and under the Roman Empire the region was united with most of Europe and North Africa in a single political and economic unit. Even areas not directly annexed became strongly influenced by the Empire which became the most powerful political and cultural entity for centuries. Although Latin culture spread into the region, the Greek culture and language first established in the region by the Macedonian Empire would continue to dominate throughout the Roman period. Cities in the Middle East, especially Alexandria, became major urban centers for the Empire and the region became the Empire's "bread basket" as the key agricultural producer.

As the Christian religion spread throughout the Empire it took root in the Middle East and cities such as Alexandria became important centers of Christian scholarship. By the 5th century, Roman Christianity was the dominant religion in the Middle East with other faiths (gradually including heretical Christian sects) being actively repressed. The Middle East's ties to the city of Rome would gradually be severed as the Empire split into East and West with the Middle East becoming tied to the new Roman capital of Constantinople. The subsequent fall of Rome and the Western Roman Empire, therefore, had minimal direct impact on the region. The Eastern Roman Empire, today commonly known as the Byzantine Empire, ruling from the Balkans to the Euphrates, became increasingly defined by and dogmatic about Christianity gradually creating religious rifts between the doctrines dictated by the establishment in Constantinople and believers in many parts of the Middle East.

The Medieval Middle East

Islamic Caliphate

- See also: Caliphate, Muslim conquests, and Islamic Golden Age

From the 7th century, a new power was rising in the Middle East, that of Islam, whilst the Byzantine Roman and Sassanid Persian empires were both weakened by centuries of stalemate warfare during the Roman-Persian Wars. In a series of rapid Muslim conquests, the Arab armies, motivated by Islam and led by the Caliphs and skilled military commanders such as Khalid ibn al-Walid, swept through most of the Middle East; reducing Byzantine lands by more than half and completely engulfing the Persian lands. In Anatolia, their expansion was blocked by the still capable Byzantines with the help of the Bulgarians. The Byzantine provinces of Roman Syria, North Africa, and Sicily, however, could not mount such a resistance, and the Muslim conquerors swept through those regions. At the far west, they crossed the sea taking Visigothic Hispania before being halted in southern France by the Franks. At its greatest extent, the Arab Empire was the first empire to control the entire Middle East, as well 3/4 of the Mediterranean region, the only other empire besides the Roman Empire to control most of the Mediterranean Sea.[1] It would be the Arab Caliphates of the Middle Ages that would first unify the entire Middle East as a distinct region and create the dominant ethnic identity that persists today. The Seljuk Empire would also later dominate the region.

Much of North Africa became a peripheral area to the main Muslim centres in the Middle East, but Iberia (Al Andalus) and Morocco soon broke from this distant control and founded one of the world's most advanced societies at the time, along with Baghdad in the eastern Mediterranean.

Between 831 and 1071, the Emirate of Sicily was one of the major centres of Islamic culture in the Mediterranean. After its conquest by the Normans the island developed its own distinct culture with the fusion of Arab, Western and Byzantine influences. Palermo remained a leading artistic and commercial centre of the Mediterranean well into the Middle Ages.

Europe was reviving, however, as more organized and centralized states began to form in the later Middle Ages after the Renaissance of the 12th century. Motivated by religion and dreams of conquest, the kings of Europe launched a number of Crusades to try to roll back Muslim power and retake the holy land. The Crusades were unsuccessful in this goal, but they were far more effective in weakening the already tottering Byzantine Empire that began to lose increasing amounts of territory to the Ottoman Turks. They also rearranged the balance of power in the Muslim world as Egypt once again emerged as a major power in the eastern Mediterranean.

Turks, Crusaders and Mongols

- See also: Crusades, History of the Levant, Timeline of Mongol invasions, and History of Jerusalem

The dominance of the Arabs came to a sudden end in the mid 11th century with the arrival of the Seljuk Turks, migrating south from the Turkic homelands in Central Asia, who conquered Persia, Iraq (capturing Baghdad in 1055), Syria, Palestine, and the Hejaz. Egypt held out under the Fatimid caliphs until 1169, when it too fell to the Turks.

Despite its massive territorial losses in the 7th century the Christian Byzantine Empire had continued to be a potent military and economic force in the Mediterranean preventing Arab expansion into much of Europe. The Seljuks' defeat of the Byzantine military in the 11th century and settling in Anatolia effectively marked the end of Byzantine influence in the region. The Seljuks ruled most of the Middle East region for the next 200 years, but their empire soon broke up into a number of smaller sultanates.

This fragmentation of the region allowed the Christian Frankish, or Holy Roman, Empire, through which Western Europe had staged a remarkable economic and demographic recovery since the nadir of its fortunes in the 7th century, to enter the region. In 1095, Pope Urban II, responding to pleas from the flagging Byzantine Empire, summoned the European aristocracy to recapture the Holy Land for Christianity, and in 1099 the knights of the First Crusade captured Jerusalem. They founded the Kingdom of Jerusalem, which survived until 1187, when Saladin retook the city. Smaller crusader fiefdoms survived until 1291.

In the early 13th century, a new wave of invaders, the Mongols of the Golden Horde, swept through the region, sacking Baghdad in 1258 and advancing as far south as the border of Egypt. Mamluk Emir Baibars left Damascus to Cairo where he was welcomed by Sultan Qutuz. After taking Damascus, Hulagu demanded that Sultan Qutuz surrender Egypt but Sultan Qutuz had Hulagu's envoys killed and, with the help of Baibars, mobilized his troops. Although Hulagu had to leave for the East when great Khan Möngke died in action against the Southern Song, he left his lieutenant, the Christian Kitbuqa, in charge. Sultan Qutuz drew the Mongol army into an ambush near the Orontes River, routed them at the Battle of Ain Jalut and captured and executed Kitbuqa. With this victory Mamluk Turks became Sultans of Egypt and the real power in the middle east and gaining control of Palestine and Syria, while other Turkish sultans controlled Iraq and Anatolia until the arrival of the Ottomans.

The Ottoman era

- See also: Ottoman Empire

By the early 15th century, a new power had arisen in western Anatolia, the Ottoman emirs, who in 1453 captured the Christian Byzantine capitol of Constantinople and made themselves sultans. The Mameluks held the Ottomans out of the Middle East for a century, but in 1514 Selim the Grim began the systematic Ottoman conquest of the region. Iraq was occupied in 1515, Syria in 1516 and Egypt in 1517, extinguishing the Mameluk line. The Ottomans united the whole region under one ruler for the first time since the reign of the Abbasid caliphs of the 10th century, and they kept control of it for 400 years.

The Ottomans also conquered Greece, the Balkans, and most of Hungary, setting the new frontier between east and west far to the north of the Danube. But in the west Europe was rapidly expanding, demographically, economically and culturally, with the new wealth of the Americas fuelling a boom that laid the foundations for the growth of capitalism and the industrial revolution. By the 17th century, Europe had overtaken the Muslim world in wealth, population and—most importantly—technology.

By 1700, the Ottomans had been driven out of Hungary and the balance of power along the frontier had shifted decisively in favour of the west. Although some areas of Ottoman Europe, such as Albania and Bosnia, saw many conversions to Islam, the area was never culturally absorbed into the Muslim world. From 1700 to 1918, the Ottomans steadily retreated, and the Middle East fell further and further behind Europe, becoming increasingly inward-looking and defensive. During the 19th century, Greece, Serbia, Romania, and Bulgaria asserted their independence, and in the Balkan Wars of 1912-13 the Ottomans were driven out of Europe altogether, except for the city of Constantinople and its hinterland.

By the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire was known as the "sick man of Europe", increasingly under the financial control of the European powers. Domination soon turned to outright conquest. The French annexed Algeria in 1830 and Tunisia in 1878. The British occupied Egypt in 1882, though it remained under nominal Ottoman sovereignty. The British also established effective control of the Persian Gulf, and the French extended their influence into Lebanon and Syria. In 1912, the Italians seized Libya and the Dodecanese islands, just off the coast of the Ottoman heartland of Anatolia. The Ottomans turned to Germany to protect them from the western powers, but the result was increasing financial and military dependence on Germany.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Middle Eastern rulers tried to modernise their states to compete more effectively with the European powers. Reforming rulers such as Mehemet Ali in Egypt, the Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II and the authors of the 1906 revolution in Persia all sought to import versions of the western model of constitutional government, civil law, secular education and industrial development into their countries. Across the region railways and telegraphs lines were built, schools and universities were opened, and a new class of army officers, lawyers, teachers and administrators emerged, challenging the traditional leadership of Islamic scholars.

Unfortunately, in all these cases the money to pay for the reforms was borrowed from the west, and the crippling debt this entailed led to bankruptcy and even greater western domination, which tended to discredit the reformers. Egypt, for example, fell under British control because the ambitious projects of Muhammad Ali and his successors bankrupted the state. Additionally, the westernisation of the Islamic world created professional armies, led by officers who were both willing and able to seize power for themselves—a problem which has plagued the Middle East ever since. There was also the problem that affects all reforming absolute rulers: they are prepared to consider all reforms except giving up their own power. Abdul Hamid, for example, grew ever more autocratic as he tried to impose reforms on his reluctant empire. Reforming ministers in Persia also tried to impose modernisation on their subjects, provoking sharp resistance.

The most ambitious reformers were the Young Turks (officially called the Committee for Union and Progress), who seized power in the Ottoman Empire in 1908. Led by an ambitious pair of army officers, Ismail Enver (Enver Pasha) and Ahmed Cemal (Cemal Pasha), and a radical lawyer, Mehmed Talat (Talat Pasha), the Young Turks initially established a constitutional monarchy, but soon became a ruling junta, with Talat as Grand Vizier and Enver as War Minister, which tried to force a radical modernisation program onto the Ottoman Empire.

The plan had several flaws. First it entailed imposing the Turkish language and centralised government on what had hitherto been a multi-lingual and loosely-governed empire, which alienated the Arabic-speaking regions of the empire and caused an upsurge in Arab nationalism. Secondly it drove the empire ever deeper into debt. And thirdly, when Enver Bey formed an alliance with Germany, which he saw as the most advanced military power in Europe, it cost the empire the support of Britain, which had protected the Ottomans against Russian encroachment all through the 19th century.

European domination

- See also: Partitioning of the Ottoman Empire

In 1914 Enver Bey's alliance with Germany led the Young Turks into the fatal step of joining Germany and Austria-Hungary in World War I, against Britain and France. The British saw the Ottomans as the weak link in the enemy alliance, and concentrated on knocking them out of the war. When a direct assault failed at Gallipoli in 1915, they turned to fomenting revolution in the Ottoman domains, exploiting the awakening force of Arab nationalism. The Arabs had lived more or less happily under Ottoman rule for 400 years, until the Young Turks had tried to "Turkicise" them and change their traditional system of government. The British found an ally in Sherif Hussein, the hereditary ruler of Mecca (and believed by Muslims to be a descendant of the family of the Prophet Muhammad), who led an Arab Revolt against Ottoman rule, having received a promise of Arab independence in exchange.

But when the Ottoman Empire was defeated in 1918, the Arab population was met with what it perceived as betrayal by the British. The British and French governments concluded a secret treaty (the Sykes-Picot Agreement) to partition the Middle East between them and, additionally, the British promised via the Balfour Declaration the international Zionist movement their support in creating a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Although historically known to be the site of the ancient Jewish Kingdom of Israel and successor Jewish nations for 1,200 years between approximately 1100BC-100AD, the area been Canaanite for 8,000 years prior to that period and had had a largely Muslim Arab population for over 1,300 years since (and a largely Byzantine Christian population in between). When the Ottomans departed, the Arabs proclaimed an independent state in Damascus, but were too weak, militarily and economically, to resist the European powers for long, and Britain and France soon established control and re-arranged the Middle East to suit themselves.

- See also: French Mandate of Syria and British Mandate of Palestine

Syria became a French protectorate thinly disguised as a League of Nations Mandate. The Christian coastal areas were split off to become Lebanon, another French protectorate. Iraq and Palestine became British mandated territories. Iraq became the "Kingdom of Iraq" and one of Sherif Husayn's sons, Faisal, was installed as the King of Iraq. Palestine became the "British Mandate of Palestine" and was split in half. The eastern half of Palestine became the "Emirate of Transjordan" to provide a throne for another of Husayn's sons, Abdullah. The western half of Palestine was placed under direct British administration. The already substantial Jewish population was allowed to increase. Initially this increase was allowed under British protection. Most of the Arabian peninsula fell to another British ally, Ibn Saud. Saud created the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in 1922.

Meanwhile, the fall of the Ottomans had allowed Kemal Atatürk to seize power in Turkey and embark on a program of modernisation and secularisation. He abolished the caliphate, emancipated women, enforced western dress and the use of Turkish in place of Arabic, and abolished the jurisdiction of the Islamic courts. In effect, Turkey, having given up rule over the Arab World, now determined to secede from the Middle East and become culturally part of Europe. Ever since, Turkey has insisted that it is a European country and not part of the Middle East.

Another turning point in the history of the Middle East came when oil was discovered, first in Persia in 1908 and later in Saudi Arabia (in 1938) and the other Persian Gulf states, and also in Libya and Algeria. The Middle East, it turned out, possessed the world's largest easily accessible reserves of crude oil, the most important commodity in the 20th century industrial world. Although western oil companies pumped and exported nearly all of the oil to fuel the rapidly expanding automobile industry and other western industrial developments, the kings and emirs of the oil states became immensely rich, enabling them to consolidate their hold on power and giving them a stake in preserving western hegemony over the region. Oil wealth also had the effect of stultifying whatever movement towards economic, political or social reform might have emerged in the Arab world under the influence of the Kemalist revolution in Turkey.

During the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s, Iraq, Syria, and Egypt made moves towards independence. In 1919, Saad Zaghlul orchestrated mass demonstrations in Egypt known as the First Revolution. While Zaghul would later become Prime Minister, the British repression of the anticolonial riots led to the death of some 800 people. In 1920, Syrian forces were defeated by the French in the Battle of Maysalun and Iraqi forces were defeated by the British when they revolted. In 1924, the independent Kingdom of Egypt was created. Although Kingdom of Egypt was technically "neutral" during World War II, Cairo soon became a major military base for the British forces and the country was occupied. The British were able to do this because of a 1936 treaty by which the United Kingdom maintained that it had the right to station troops on Egyptian soil in order to protect the Suez Canal. In 1941, the Rashīd `Alī al-Gaylānī coup in Iraq led to the British invasion of the country during the Anglo-Iraqi War. The British invasion of Iraq was followed by the Allied invasion of Syria-Lebanon and the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran.

In the region of Palestine the conflicting forces of Arab nationalism and Zionism created a situation which the British could neither resolve nor extricate themselves from. The rise to power of German dictator Adolf Hitler in Germany had created a new urgency in the Zionist quest to immigrate to Palestine and create a Jewish state there. A Palestinian state was also an attractive alternative for Arab and Persian leaders to British, French, and perceived Jewish colonialism and imperialism under the logic of "the enemy of my enemy is my friend" (Lewis, 348-350).

The British, the French, and the Soviets departed many parts of the Middle East during and after World War II. Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and the Middle East states on the Arabian Peninsula generally remained unaffected by World war II. However, after the war, the following Middle states had independence restored or became independent:

- 17 October 1941 - Iran (forces of the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union withdrawn)

- 8 November 1943 - Lebanon

- 1 January 1944 - Syria

- 22 May 1946 - Jordan (British mandate ended)

- 1947 - Iraq (forces of the United Kingdom withdrawn)

- 1947 - Egypt (forces of the United Kingdom withdrawn to the Suez Canal area)

- See also: Arab-Israeli conflict, History of the Arab-Israeli conflict, History of Palestine, and History of Israel

The struggle between the Arabs and the Jews in Palestine culminated in the 1947 United Nations plan to partition Palestine. This plan attempted to create an Arab state and a Jewish state in the narrow space between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea. While the Jewish leaders accepted it, the Arab leaders rejected this plan.

On 14 May 1948, when the British Mandate expired, the Zionist leadership declared the State of Israel. In the 1948 Arab-Israeli War which immediately followed, the armies of Egypt, Syria, Transjordan, Lebanon, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia intervened and were defeated by Israel. About 800,000 Palestinians fled from areas annexed by Israel and became refugees in neighbouring countries, thus creating the "Palestinian problem" which has bedevilled the region ever since. Approximately two-thirds of 758,000—866,000 of the Jews expelled or who fled from Arab lands after 1948 were absorbed and naturalized by the State of Israel.

A zone of conflict

- See also: List of conflicts in the Middle East

The departure of the European powers from direct control of the region, the establishment of Israel, and the increasing importance of the oil industry, marked the creation of the modern Middle East. These developments led to a growing presence of the United States in Middle East affairs. The U.S. was the ultimate guarantor of the stability of the region, and from the 1950s the dominant force in the oil industry. When republican revolutions brought radical anti-western regimes to power in Egypt in 1954, in Syria in 1963, in Iraq in 1968 and in Libya in 1969, the Soviet Union, seeking to open a new arena of the Cold War in the Middle East, allied itself with Arab rulers such as Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt and Saddam Hussein of Iraq. These regimes gained popular support through their promises to destroy the state of Israel, defeat the U.S. and other "western imperialists," and to bring prosperity to the Arab masses. When they failed to deliver on their promises, they became increasingly despotic.

In response to this challenge to its interests in the region, the U.S. felt obliged to defend its remaining allies, the conservative monarchies of Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Iran and the Persian Gulf emirates, whose methods of rule were almost as unattractive to western eyes as those of the anti-western regimes. Iran in particular became a key U.S. ally, until a revolution led by the Shi'a clergy overthrew the monarchy in 1979 and established a theocratic regime which was even more anti-western than the secular regimes in Iraq or Syria. This forced the U.S. into a close alliance with Saudi Arabia, a reactionary, corrupt and oppressive monarchy, and a regime, moreover, dedicated to the destruction of Israel. The list of Arab-Israeli wars includes a great number of major wars such as 1948 Arab-Israeli War, 1956 Suez War, 1967 Six Day War, 1970 War of Attrition, 1973 Yom Kippur War, 1982 Lebanon War, as well as a number of lesser conflicts.

In 1979, Egypt under Nasser's successor, Anwar Sadat, concluded a peace treaty with Israel, ending the prospects of a united Arab military front. From the 1970s the Palestinians, led by Yasser Arafat's Palestine Liberation Organization, resorted to a prolonged campaign of violence against Israel and against American, Jewish and western targets generally, as a means of weakening Israeli resolve and undermining western support for Israel. The Palestinians were supported in this, to varying degrees, by the regimes in Syria, Libya, Iran and Iraq. The high point of this campaign came in the 1975 United Nations General Assembly Resolution 3379 condemning Zionism as a form of racism and the reception given to Arafat by the United Nations General Assembly. The Resolution 3379 was revoked in 1991 by the UNGA Resolution 4686.

The fall of the Soviet Union and the collapse of communism in the early 1990s had several consequences for the Middle East. It allowed large numbers of Soviet Jews to emigrate from Russia and Ukraine to Israel, further strengthening the Jewish state. It cut off the easiest source of credit, armaments and diplomatic support to the anti-western Arab regimes, weakening their position. It opened up the prospect of cheap oil from Russia, driving down the price of oil and reducing the west's dependence on oil from the Arab states. And it discredited the model of development through authoritarian state socialism which Egypt (under Nasser), Algeria, Syria and Iraq had been following since the 1960s, leaving these regimes politically and economically stranded. Rulers such as Saddam Hussein in Iraq increasingly turned to Arab nationalism as a substitute for socialism.

It was this which led Iraq into its prolonged war with Iran in the 1980s, and then into its fateful invasion of Kuwait in 1990. Kuwait had been part of the Ottoman province of Basra before 1918, and thus in a sense part of Iraq, but Iraq had recognised its independence in the 1960s. The U.S. responded to the invasion by forming a coalition of allies which included Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Syria, gaining approval from the United Nations and then evicting Iraq from Kuwait by force in the Persian Gulf War. President George H. W. Bush did not, however, attempt to overthrow Saddam Hussein's regime, something the U.S. later came to regret. The Persian Gulf War and its aftermath brought about a permanent U.S. military presence in the Persian Gulf region, particularly in Saudi Arabia, something which caused great offence to many Muslims.

The conflicts continued in 2006 with the so-called 'July War' between Israel and Hizbullah militants. What had been a long-running, localized conflict between Israeli forces and Palestinian militants in the Gaza Strip flared up on July 12, 2006 when Hezbollah militants captured 2 Israeli soldiers patrolling along the Israeli-Lebanese border. This resulted in what is called the July War in Lebanon, which lasted just over a month, in which more than 1000 Lebanese civilians were killed and around 120 Israeli soldiers were killed, both Israel and Lebanon were subjected to constant shelling and air strikes by Hezbolla and Israel, respectively. Air strikes and rocket attacks became commonplace between Israeli forces and the Hezbollah militia as the Israelis attempted to clear a security zone along the Israeli-Lebanese border free of Israeli forces and Hezbollah militants. A recent Report for Congress [1] argued that indirect involvement of Iran and Syria, in that they allow and help the 'arming, training and financing' of Hezbollah, means that the month-long war was really a direct conflict between Israel and Iran-Syria by proxy.

The contemporary Middle East

By the 1990s, many western commentators (and some Middle Eastern ones) saw the Middle East as not just a zone of conflict, but also a zone of backwardness. The rapid spread of political democracy and the development of market economies in Eastern Europe, Latin America, East Asia and parts of Africa passed the Middle East by boats. In the whole region, only Israel, Turkey and to some extent Lebanon and the Palestinian territories were democracies. Other countries had legislative bodies, but these had little power, and in the Gulf states the majority of the population could not vote anyway, as they were guest workers and not citizens. Many Arab commentators counter claim that as a direct result of Western foreign policy, an overstrong Israel, double standards of occupation, and destroying a nation which was extremely prosperous in the 1980s under Saddam Hussein by form of sanctions, and interference was removed much progress would come naturally to these nations.

In most Middle Eastern countries, the growth of market economies was inhibited by political restrictions, corruption and cronyism, overspending on arms and prestige projects, and overdependence on oil revenues. The successful economies in the region were those which combined oil wealth with low populations, such as Qatar, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates. In these states, the ruling emirs allowed a certain degree of political and social liberalization, yet without giving up any of their own power. Lebanon, after a prolonged civil war in the 1980s, also rebuilt a fairly successful economy.

By the end of the 1990s, the Middle East as a whole was falling behind Europe, India, China, and other rapidly developing market economies, in terms of production, trade, education, communications and virtually every other criterion of economic and social progress. The assertion that, if oil was subtracted, the total exports of the whole Arab world were less than those of Finland was frequently quoted. The theories of authors such as David Pryce-Jones, that the Arabs were trapped in a "cycle of backwardness" from which their culture would not allow them to escape, were widely accepted in the west and east.

In the opening years of the 21st century all these factors combined to raise the Middle East conflict to a new height, and to spread its consequences across the globe. The failure of the attempt by Bill Clinton to broker a peace deal between Israel and the Palestinians at Camp David in 2000 (2000 Camp David Summit) led directly to the election of Ariel Sharon as Prime Minister of Israel and to the Al-Aqsa Intifada, characterised by suicide bombing of Israeli civilian targets. This was the first major outbreak of violence since the Oslo Peace Accords of 1993.

At the same time, the failures of most of the Arab regimes and the bankruptcy of secular Arab radicalism led a section of educated Arabs (and other Muslims) to embrace Islamism, promoted both by the Shi'a clerics of Iran and by the powerful Wahhabist sect of Saudi Arabia. Many of the militant Islamists gained military training while fighting against the forces of the Soviet Union in Afghanistan.

One of these was a wealthy Saudi Arabian, Osama bin Laden. After fighting against the Soviets in Afghanistan, he formed the al-Qaida organization, which was responsible for the 1998 U.S. embassy bombings, the USS Cole bombing and the September 11, 2001 attacks on the United States. The September 11 attacks led the administration of U.S. President George W. Bush to launch an invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 to overthrow the Taliban regime, which was harbouring Bin Laden and his organisation. The U.S. and its allies described this operation as part of a global "War on Terrorism."

The U.S. and Britain also became convinced that Saddam Hussein was reconstituting Iraq's weapons of mass destruction program, in violation of the agreements it had given at the end of the Persian Gulf War. During 2002 the administration, led by Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, developed a plan to invade Iraq, remove Saddam from power, and turn Iraq into a democratic state with a free-market economy, which, they hoped, would serve as a model for the rest of the Middle East. When the U.S. and its principal allies, Britain, Italy, Spain and Australia, could not secure United Nations approval for the execution of the numerous United Nations resolutions, they launched an invasion of Iraq, overthrowing Saddam with no great difficulty in April 2003. However, some believe, the whole invasion of Iraq is completely, an oil-driven war.

The advent of a new western army of occupation in a Middle Eastern capital marked a turning point in the history of the region. Despite successful elections (although boycotted by large portions of Iraq's Sunni population) held in January 2005, Iraq has all but disintegrated due to a lack of infrastructure and security. A post-war insurgency has morphed into persistent ethnic violence the American army has been unable to quell. Many of Iraq's intellectual and business elite have fled the country, and total Iraqi refugees already outnumber the Palestinian exodus following the creation of Israel, further destabilizing the region. A responsive surge in US forces in Iraq has recently been largely successful in controlling the insurgency and stabilizing Iraq.

By 2005, also, George W. Bush's Road map for peace between Israel and the Palestinians has been stalled, although this situation began to change with Yasser Arafat's death in 2004. In response, Israel moved towards a unilateral solution, pushing ahead with the Israeli West Bank barrier to protect Israel from Palestinian suicide bombers and proposed unliteral withdrawal from Gaza. The barrier if completed would amount to a de facto annexation of areas of the West Bank by Israel. In 2006 a new conflict erupted between Israel and Hezbollah Shi’a militia in southern Lebanon, further setting back any prospects for peace.

References

- Lewis, Bernard. The Middle East: A Brief History of the Last 2,000 Years. New York: Scribner, 1995.

- Sharp, Jeremy (2006-09-15). "CRS Report for Congress -- Lebanon: The Israel-Hamas-Hezbollah Conflict", CRS Online. Retrieved on 2006-01-20.

See also

- History of Afghanistan

- History of Armenia

- History of Azerbaijan

- History of Bahrain

- History of Djibouti

- History of Egypt

- History of Eritrea

- History of Ethiopia

- History of Iran

- History of Iraq

- History of Israel

- History of Jordan

- History of Kuwait

- History of Lebanon

- History of Oman

- History of Pakistan

- History of Palestine

- History of Qatar

- History of Saudi Arabia

- History of Somalia

- History of Syria

- History of Turkey

- History of the United Arab Emirates

- History of Yemen

- History of ancient Israel and Judah

- History of the Kurds

- Southwest Asia

- North Africa

- Northeast Africa

- Timeline of Middle Eastern History

- Synoptic table of the principal old world prehistoric cultures