History of Lithuania

This article discusses the history of Lithuania and of the Lithuanians. Lithuania for the first time in writing sources was mentioned in 1009.[1] Later Lithuanians conquered neighboring lands, finally establishing Kingdom of Lithuania in the 13th century. In the 15th century Lithuania became the largest state in Europe[2] however in the 18th century it was erased from political map. Finally, in February 16, 1918 was reestablished democratic state. It faced many drawbacks including many deaths in World War II and further catastrophe after being annexed by the Soviet Union. In the early 1990s Lithuania restored its sovereignty and continued to grow into an economically strong country.

Before statehood

The first people arrived to the territory of modern Lithuania in the 10th millennium BC after glaciers had retreated and the last glacial period had ended. According to historian Marija Gimbutas, the people came from two directions: from the Jutland Peninsula and from present-day Poland. They brought two different cultures as evidenced by the tools they used. They were traveling hunters and did not form more stable settlements. In the 8th millennium BC the climate became much warmer and forests developed. The people started to gather berries and mushrooms from the forests and fish in the local rivers and lakes. They traveled less. During the 6th–5th millennium BC people domesticated various animals, the houses became more sophisticated and could shelter larger families. Agriculture came late, only in the 3rd millennium BC because there were no efficient tools to cultivate the land. At the same time crafts and trade started to form. The Proto-Indo-Europeans came around 2500 BC and the identity of the Balts formed about 2000 BC.

Baltic tribes

The first Lithuanians, were a branch of an ancient group known as the Balts, whose tribes also included the original Prussian and Latvian people. The Baltic tribes were not directly influenced by the Roman empire, but the tribes did maintain close trade contacts (see Amber Road).

Lithuanians have built a nation that has endured for most of the past ten centuries, while Latvians acquired statehood in the 20th century and Prussian tribes disappeared in the 18th century. The first known reference to Lithuania as a nation (Litua) comes from the annals of the monastery of Quedlinburg dated February 14, 1009.

In the present day the two remaining Baltic nationalities are Lithuanians and Latvians, but there have, in the past, been more such nationalities/tribes; some of which nationalities have merged into the Lithuanian and Latvian nationalities (Samogitians, Selonians, Curonians, Semigallians), while others have been completely destroyed (Prussians, Sambians, Skalvians, Galindians).

Towards the creation of single state

During the 11th century Lithuanian territories were included into the list of lands paying tribute to Kievan Rus', but by the 12th century, the Lithuanians were plundering neighboring territories themselves. The military and plundering activities of the Lithuanians triggered a struggle for power in Lithuania which began the formation of early statehood, and was a precondition of the founding of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Grand Duchy of Lithuania

Pagan Lithuania

In the early 13th century two German religious orders, the Teutonic Knights and the Livonian Brothers of the Sword, conquered much of the area that is now Estonia and Latvia, in addition to parts of Lithuania. In response, a number of small Baltic tribal groups united under the rule of Mindaugas (Myndowe) and soundly defeated the Livonians at Šiauliai in the Battle of Saule in 1236. In 1250 Mindaugas signed an agreement with the Teutonic Order and in 1251 was baptized in their presence by the bishop of Chełmno (in Chełmno Land.) On 6 July 1253, Mindaugas was crowned as King of Lithuania and state was proclaimed as Kingdom of Lithuania. However, Mindaugas was later murdered by his nephew Treniota which resulted in great unrest and a return to paganism. In 1241, 1259 and 1275 the kingdom was ravaged by raids from the Golden Horde.

In 1316, Gediminas, with the aid of colonists from Germany, began restoration of the land. The brothers Vytenis and Gediminas united various groups into one Lithuania.

Gediminas extended Lithuania to the east by challenging the Mongols who, at that time, Mongol invasion of Rus'. Through alliances and conquest the Lithuanians gained control of significant parts of the territory of Rus. This area included most of modern Belarus and Ukraine and created a massive Lithuanian state that stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea.

When Gediminas was slain, his son Algirdas (Olgierd) suppressed the monasteries, but Algirdas's son, Jogaila (Jagiello), again made overtures to the Teutonic Order and concluded a secret treaty with them. His uncle Kęstutis took him prisoner and a civil war ensued. Kęstutis was eventually captured, imprisoned and put to death, but Kęstutis's son Vytautas escaped.

Nowadays Lithuanian paganism is practised by Ancient Baltic faith community 'Romuva'.

Christian Lithuania

Jadwiga of Poland was strongly urged by the Poles to marry Jogaila who had become the Grand Duke of Lithuania in 1377 and for the good of Christianity, Jadwiga consented and married Jogaila three days after he was baptized. Jogaila and Lithuanians in general favoured this marriage as the alliance with Poland gave them a powerful ally against the constant threat of Germany (especially the Teutonic Knights based in Prussia) and Muscovy from the east.

On February 2, 1386, the Polish Parliament (Sejm) elected Jogaila as King of Poland. This meant that Lithuanian ruler get another crown of and Poland, and Lithuania remained a separate country and continued to be ruled by the Grand Duke of Lithuania. Before Jogaila was Crowned as a king of Poland, the second and the final Christianization of Lithuania was carried out.

Lithuania remained sovereign state but the highest social class in Lithuanian nobility became increasingly influenced by Christian culture and language and the countries grew closer. Many cities were granted the German system of laws (Magdeburg rights), with the largest of these being Vilnius, which since 1322 was the capital city of Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Lithuanian Renaissance

In the 16th century, when many educated Lithuanians came back from studies abroad, Grand Duchy of Lithuania was boiling with active cultural life, sometimes referred to as Lithunanian Renaissance (not to be confused with Lithuanian National Revival in 19th century).

At the time Italian architecture was introduced in Lithuanian cities, and Lithuanian literature written in Latin flourished. Also at the time emerged first handwritten and printed texts in the Lithuanian language, and began the formation of written Lithuanian language. The process was led by Lithuanian scholars Abraomas Kulvietis, Stanislovas Rapalionis, Martynas Mažvydas and Mikalojus Daukša.

Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth (1569–1795)

With the Union of Lublin of 1569 Poland and Lithuania formed a new state: the Republic of Both Nations (commonly known as Poland-Lithuania or the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth; Polish: Rzeczpospolita Obojga Narodow, Lithuanian: Abiejų Tautų Respublika).

Following the union, Polonization started to take place in Lithuanian public life, and took another 140 years to become a major factor. Under the influence of the Lithuanian upper classes and the church, who began to use Polish language more frequently. In 1696 Polish became an official language, replacing the previous Lithuanian language and Ruthenian languages. Despite the Union and integration of the two countries, for nearly two centuries Lithuania continued to exist as the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, retaining separate laws as well as an Army and a Treasury.

The Constitution of May 3, 1791, agreed by the Sejm attempted to integrate Lithuania and Poland more closely, although the separation was kept by the October 20th addendum to the May the 3rd Constitution. However, partitions of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1772, 1793 and 1795 saw Lithuania divided between Russia and Prussia and Lithuania ceased to exist as a distinct entity for more than a century.

Under Imperial Russia (1795–1914)

Domination of Russia

Following the third partition, the Russian Empire controlled the majority of Lithuania, including Vilnius, making up a part of Vilna Governorate.

In the early years of the 19th century, there were signs that Lithuania might be allowed some separate recognition by the Empire, however it was never realized.

Napoleon's invasion

These hopes were soon to be dashed, particularly subsequent to 1812, when Lithuanians eagerly welcomed Napoleon Bonaparte's French army as liberators. After the French army's withdrawal, Tsar Nicholas I began an intensive program of Russification. The south-western part of Lithuania included in Prussia in 1795 and in the short-lived Duchy of Warsaw in 1807 became a part of the Russian-controlled Kingdom of Poland in 1815, while the rest of Lithuania continued to be administered as a Russian province.

Uprisings

The Lithuanians and Poles revolted twice, in 1831 and 1863, but both attempts failed. In 1864 the Lithuanian language and the Latin alphabet were banned in junior schools. Lithuanians resisted the Russification by arranging printing abroad and smuggling the books in by knygnešiai.

Lithuanian national revival

Under late Russian occupation, the native language of Lithuania was reborn after many years of dormancy.

Because many of Lithuanian nobles were Polonized and only the poor and middle classes used Lithuanian (but some of the latter also tended to use Polish for "prestige"), Lithuanian was not considered a prestigious language. There were even expectations that the language would become extinct, as more and more territories in the east were Slavicized, and more people used Polish or Russian in daily life. The only place where Lithuanian was considered to be more prestigious and worthy of books and such was German-controlled Lithuania Minor. Even here, an influx of German immigrants threatened the native language and culture.

The revival started among poor people, then continued with the wealthy, beginning with the release of Lithuanian newspapers, Aušra and Varpas, then with the writing of poems and books in Lithuanian. These writings glorified the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, depicting the nation with power and many heroes.

This revival spearheaded the independence movement, with various organizations opposing Russian influence. Russian policy became harsher in response. Strikes were organized against Catholic churches while a ban forbidding Lithuanian press continued.

Lithuania's nationalist movement continued to grow. During the Russia-wide revolutionary uprising of 1905 a congress (Great Seimas of Vilnius) of Lithuanian representatives in Vilnius on 5 December 1905 demanded provincial autonomy. For its part, the tsarist regime did make a number of concessions as the result of the 1905 uprising. The Baltic states could once again use their native languages in schooling and public discourse. Roman script replaced the Cyrillic script which had been forced upon Lithuanian for four decades. However, not even Russian liberals were prepared to concede autonomy similar to that as had already existed in Estonia and Latvia, albeit under Baltic German hegemony.[3]

Under Bismark, German policy had aligned itself with tsarist Russia along the lines of Prussian alliances extending back to the Napoleonic era, in line with their both being politically aligned against Poland. When relations deteriorated between Germany and Russia, it was not over the Baltics but over the conflict between Austria and Russia in the Balkans. While many Baltic Germans had looked toward aligning the Baltics with Germany—Lithuania and Courland in particular—they had taken no overt action. However, with the outbreak of hostilities in World War I and Germany's occupation of Lithuania and Courland in 1915, the Baltic Germans now had the real possibility of aligning themselves with Germany, opposing both tsarist Russia and Lithuanian nationalism.[3]

- See also: Great Seimas of Vilnius

Independent Lithuania (1918–1940)

Declaration of independence

During World War I Lithuania was incorporated into Ober Ost, occupational German government. As the war progressed, it became evident that Germany would not reach an effective victory and would have to compromise peace with the Russian Empire.[4] As open annexation could result in a public relations backlash, Germans planned to form a network of formally independent states that would in fact be completely dependent on Germany, the so-called Mitteleuropa.[5] Germans allowed Vilnius Conference (September 18 – September 22, 1917) to convene demanding that Lithuanians declare loyalty to Germany and agree to an annexation. The Conference elected 20-member Council of Lithuania and empowered it to act as the executive authority of the Lithuanian people.[5] The Council adopted the Act of Independence of Lithuania on February 16, 1918. It declared that Lithuania is an independent republic, organized based on democratic principles. Germans, still present in the country, did not support such a declaration and hindered any attempts to establish the proclaimed independence. To prevent being incorporated into the German Empire, Lithuanians elected Monaco-born King Mindaugas II as the titular monarch of the Kingdom of Lithuania in July 1918. Mindaugas II never assumed the throne.

Germany lost the war and signed the Armistice of Compiègne on November 11, 1918. Lithuanians quickly formed their first government, led by Augustinas Voldemaras, adopted a provisional constitution, and started organizing basic administrative structures. As the defeated German army was withdrawing from the Eastern Front, it was followed by Soviet forces in order to spread the global proletarian revolution. They created a number of puppet states, including the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic. By the end of December the Red Army reached Lithuanian borders starting the Lithuanian–Soviet War. The Lithuanian government evacuated from Vilnius to Kaunas, the temporary capital of Lithuania. Vilnius was captured on January 5, 1919. As Lithuanian army was in its infant stages, Soviet forces moved largely unopposed and by mid-January 1919 controlled about ⅔ of Lithuanian territory. From April 1919 the Lithuanian war went parallel with the Polish–Soviet War. Poland had territorial claims over Lithuania, especially the Vilnius Region, and these tensions spilled over into the Polish–Lithuanian War. In mid-May the Lithuanian army, now commanded by General Silvestras Žukauskas, began an offensive against the Soviets in northeastern Lithuania. By the end of August 1919, Soviets were pushed out of the Lithuanian territory. When the Soviets were defeated, Lithuanian army was deployed against the Bermontians, who invaded northern Lithuania. They were rouse German and Russian soldiers who sought to retain German control over the former Ober Ost. Bermontians were defeated and pushed out by the end of 1919. Thus the first phase of the Lithuanian Wars of Independence was over and Lithuanians could direct attention to internal affairs.

Democratic Lithuania

The Constituent Assembly of Lithuania was elected in April and first met in May 1920. In June it adopted the third provisional constitution and in July signed the Soviet–Lithuanian Peace Treaty. In the treaty the Soviet Union recognized fully independent Lithuania and its claims to the disputed Vilnius Region. The treaty increased hostilities between Poland and Lithuania. To prevent further fighting, the Suwałki Agreement was signed in October. But before it went into effect, Polish General Lucjan Żeligowski staged a mutiny, invaded Lithuania, captured Vilnius, and established short-lived Republic of Central Lithuania. The League of Nations attempted to mediate the dispute and Paul Hymans proposed plans of Polish–Lithuanian union. However, the negotiations broke down as neither side agreed to compromise. The Central Lithuania held a plebiscite and was incorporated into Poland in March 1922. The dispute for the Vilnius Region was not resolved. Lithuania broke any diplomatic relation with Poland refusing to recognize, even de facto, its control over Vilnius, historical capital of Lithuania with significant Polish population. The dispute continued to dominate Lithuanian foreign policy for the entire interwar period.

The Constituent Assembly, which adjourned in October 1920 due to threats from Poland, gathered again and initiated many reforms needed in the new state: obtained international recognition and membership in the League of Nations, passed the law of land reform, introduced national currency litas, and adopted the final constitution in August 1922. Lithuania became a democratic state, with Seimas (parliament) elected by men and women for a three-year term. The Seimas elected the president. The First Seimas was elected in October 1922, but could not form a government as the votes split equally 38–38 and was forced to resign. Its only lasting achievement was the Klaipėda Revolt in January 1923. Lithuania took advantage of the Ruhr Crisis and captured the Klaipėda Region, a territory detached from the East Prussia according to the Treaty of Versailles and placed under french administration. The region was incorporated as an autonomous district of Lithuania in May 1924. For Lithuania it was the only access to the Baltic Sea and important industrial center. The Revolt was the last armed conflict in Lithuania before World War II. The Second Seimas, elected in May 1923, was the only Seimas in independent Lithuania that served the full term. The Seimas continued the land reform, introduced social support systems, started repaying foreign debt. Strides were made in education: the network of primary and secondary schools was expanded and first universities were established in Kaunas.

Authoritarian Lithuania

The Third Seimas, was elected in May 1926. For the first time Lithuanian Christian Democrats (krikdemai) lost their majority and became an opposition. It was sharply criticized for signing the Soviet–Lithuanian Non-Aggression Pact and accused of "Bolshevization" of Lithuania. As a result of growing tensions, the government was deposed during the 1926 Lithuanian coup d'état in December. The coup, organized by the military, was supported by the Lithuanian Nationalists Union (tautininkai) and Lithuanian Christian Democrats. They installed Antanas Smetona as the President and Augustinas Voldemaras as the Prime Minister.[6] Smetona suppressed its opposition and remained as an authoritarian leader until June 1940.

The Seimas though that the coup was just a temporary measure and the new elections should be called to return to democratic Lithuania. It was dissolved in May 1927. Later that year members of Social Democrats and other leftist parties, named plečkaitininkai after their leader, tried to organize an uprising against Smetona but were quickly subdued. Voldemaras grew increasingly independent of Smetona and was forced to resign in 1929. Three times in 1930 and once in 1934 he unsuccessfully attempted to return to power. In May 1928 Smetona, without the Seimas, announced the fifth provisional constitution. It continued to claim that Lithuania is a democratic state and vastly increased powers of the President. His party, the Lithuanian National Union, steadily grew in size and importance. Smetona adopted the title of "tautos vadas" (leader of the nation) and slowly started building personality cult. Many of the prominent political figures married into Smetona's family (Juozas Tūbelis, Stasys Raštikis).

When the Nazi Party came into power in the Weimar Republic, Germany–Lithuania relations worsened considerably as Nazi Germany did not accept the loss of Klaipėda Region. The Nazis sponsored anti-Lithuanian organizations in the region. In 1934, Lithuania put the activists on trial and sentenced about 100 people, including their leaders Ernst Neumann and Theodor von Sass. That prompted Germany, one of the main trade partners of Lithuania, to declare embargo of Lithuanian products. In response Lithuania shifted its exports to Great Britain. But that was not enough and peasants in Suvalkija organized strikes, which were violently suppressed. Smetona's prestige was damaged and in September 1936 he agreed to call the first elections to Seimas since the coup in 1926. Before the elections all political parties, except the National Union, were closed. Thus of 49 members of the Fourth Seimas, 42 were from the National Union. It functioned as an advisory board to the President and in February 1938 adopted a new constitution, which granted even greater powers to the President.

As tensions were rising in Europe following the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany, Poland presented an ultimatum to Lithuania in March 1938. Poland demanded the re-establishment of normal diplomatic relations, which were broken after the Żeligowski's Mutiny in 1920, and threatened military actions in case of refusal. Lithuania, having weaker military power and unable to enlist international support for its cause, accepted the ultimatum. Lithuania–Poland relations somewhat normalized and the parties concluded treaties regarding railway transport, postal exchange, and other means of communication. Just a year after the Polish ultimatum and five days after the German occupation of Czechoslovakia, Lithuania received as oral ultimatum from Joachim von Ribbentrop demanding to cede the Klaipėda Region to Germany. Again, Lithuania was forced to accept. This triggered a political crisis in Lithuania and forced Smetona to form a new government which for the first time since 1926 included members of the opposition. The loss of Klaipėda was a major blow to Lithuanian economy and the country shifted to the sphere of German influence. When Germany and the Soviet Union concluded the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact in 1939 and divided Eastern Europe into spheres of influence, Lithuania was, at first, assigned to Germany.

World War II (1939–1945)

First Soviet occupation

In August 1939, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed an agreement (the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact), with secret clauses assigning spheres of influence in the area of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania was initially assigned to the German sphere of influence, but when Lithuania refused to ally with Nazi Germany in the attack on Poland, it was transferred to the Soviets in another secret pact later that year.

The city of Vilnius was occupied by the Red Army and later transferred to Lithuania together with only one fifth of the Vilnius region. The Soviets established their military presence within the country.

Despite having a non-aggression pact signed and in force, Soviet Russia gave Lithuania an ultimatum in 1940. It demanded to remove from the legal position several key Lithuanian politicians under the pretext of a supposed kidnapping of several deserted Soviet soldiers and asked them to be imprisonment by Soviet troops. (the incident was staged by the Russians themselves). In the ultimatum Soviets demanded to deploy overwhelming military units in the Lithuanian territory.

Unlike Finland, Lithuania did not stage an armed opposition and accepted the ultimatum. President Antanas Smetona opposed it and insisted that Lithuania should hold an armed opposition against advancing Soviet troops, while most of members of the government decided that it should be accepted, assuming that Lithuania would have lost a war against Russia in any case, so, the ultimatum was accepted.

Smetona left Lithuania to prevent legalization of the inevitable occupation, as the Soviet military forces (15 divisions, about 150,000 soldiers) crossed the Lithuanian border on June 15, 1940, the military of Lithuania was ordered not to resist.

With the support of Soviet military forces, a new government was formed by occupying Soviet forces. The illegitimate government consisted mainly of leftist Lithuanians, who were sponsored for a long time by Soviets—(such as leftist poets like Salomėja Nėris, Antanas Venclova), that according to the censored press was supposedly to be more popular among the general public. 200,000 families requested land nationalized from well doing farmers, who were prepared to be deported to Siberia. Puppet-Government members were nominated according to the orders of Vladimir Dekanozov, the Soviet envoy in Lithuania. Dekanozov named Justas Paleckis, a Lithuanian leftist who at the time was not yet a member of the Communist Party, although enjoyed sponsorship for Soviet embassy in Kaunas for a long time, as a frontman Prime Minister. The selection of a prime minister acceptable to Moscow was not carried out according to the procedures foreseen in the Lithuanian constitution; rather, aided by specialists sent in from Moscow, Dekanozov staged the elections through the Lithuanian Communist Party, headed by Antanas Sniečkus, while the cabinet of ministers, headed by Paleckis, served an a puppet-administrative function.

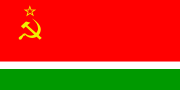

This temporary government was in office for a very short period, and on July 14–15, 1940, elections to the so-called "People's Parliament" were organized. However, only the Communist Party of Lithuania could nominate candidates, with its leaders being returned from Moscow or released from prisons. On July 21, 1940, the parliament declared Lithuania's will to join the Soviet Union and on August 3, 1940, the Supreme Council of the USSR "admitted" Lithuania into the Soviet Union. The process of annexation was formally over and the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic was created.

Nazi occupation

On June 22, 1941, Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union. Lithuanians declared independence expectating that the Soviets would weaken and wouldn't have enough strength to hold Lithuania. On June 24 1941, Juozas Ambrazevičius, a member of the Lithuanian Activist Front (Lietuvos aktyvistų frontas, LAF), became prime minister. The retreating Soviet forces massacred Lithuanian political prisoners in the Rainiai massacre.

The leader of the LAF was Kazys Škirpa, who was in Berlin, away from Soviet occupation. However, the Germans did not let him leave because Nazi Germany did not want an independent Lithuania and planned for it to be a part of its occupied territories. The new government asked people via radio not to loot and to remain in place with the retreat of Soviet army, and declared Lithuania independent again.

At this time the government tried to negotiate with Germany to allow Lithuanian independence. German troops had entered Lithuania, but for propaganda purposes and other reasons, they did not immediately dissolve the government of Lithuania (and this created a false belief among some Lithuanians that Germans would permit Lithuania to stay independent or at least autonomous).

However, with time Germans gradually stripped the Lithuanian government of its powers; Lithuania, having no regular army, was unable to resist because of the huge disparity of strength and ultimately the Germans annexed Lithuania. The government, no longer having any real power, dissolved itself on August 7, 1941. The Lithuanian Activist Front was subsequently banned by the German authorities.

German actions

People soon realized that the Nazis had no plans for an independent or even autonomous Lithuania and the German occupation administration viewed the natives as second-class citizens. Germany annexed a small part of southern Lithuania to the Reich itself (Balstogė county), while the Lithuanian part of Ostland acquired some more lands from the Vilnius region: Ašmena, Svyriai, etc. This region was not part of the territory given to Lithuania by the Soviets some years previously when Vilnius itself was acquired from occupied Polish territory. Lithuania lost its independence fully.

Economic conditions were harsh, especially in cities and towns. In the countryside people were at least able to grow food for themselves and did not suffer the same hardships.

Resistance

The migration of thousands of German settlers into territories formerly belonging to Lithuanian farmers, along with the dismissal and suppression of the independent Lithuanian government, soon produced a vigorous resistance movement. The resistance movement was not however united — the majority fought for an independent Lithuania; but another group of pro-Soviet partisans, which mainly consisted of Russians, Belarusians and Jews, operated in eastern Lithuania. This group fought for the re-incorporation of Lithuania into the Soviet Union. Soviet partisans committed a number of atrocities (for example, the Koniuchy massacre) and sacked towns and villages.[7]

The Polish Armia Krajowa (AK) also operated on Lithuanian territory, expecting post-war Poland to resume control of the Vilnius/Wilno region. AK was fighting not only against the Nazis, but also against the pro-Nazi Lithuanian police, Lithuanian Territorial Defense Force, and the Soviet partisans. Relationships between different guerilla detachments was never cordial and worsened as the war went on.

Relations between German forces and Lithuanian people

There was substantial cooperation and collaboration between the German forces and some Lithuanians. The Lithuanian Activist Front group formed five police companies to restore order in the country. Later, the units around Kaunas were incorporated into the Tautos Darbo Apsauga (National Labour Guard) and in Vilnius the Lietuvos Savisaugos Dalys (Lithuanian Self Defence). These were then joined into the Policiniai Batalionai (Lithuanian Police Battalions) called by the Germans the Schutzmannschaft, with a total of 8,388 men by August, 1942. Another infamous unit was the Lithuanian Security Police (Saugumo policija).

Despite the fact that the purpose of their creation was different, these Lithuanian units participated in the Jewish Shoah, especially within Lithuania and the areas of the Vilnius region that are now in Belarus. It is alleged that in October and November 1941 Lithuanian Schutzmannschaft Battalion 2 participated in the killing of 19,000 Jews,[8] that in 1942 the Schutzmannschaft 7th company was involved in the murder of 9,200 Jews, and that the Lithuanian Schutzmannschaft Battalion 254E killed at least 1,800 Jews in the course of a single action in 1943.[9]

An SS division was not established in Lithuania but other military units with about 30,000 Lithuanian inductees were created.[10] Eventually, the Lithuanian general Povilas Plechavičius, who commanded the collaborationist forces, dismissed his soldiers upon finding out that the Nazi regime was planning to mould them into a division of the Nazi elite corps.

There was also resistance to the German occupation, and some Lithuanians risked their own lives to save Jews. 504 Lithuanians are recognized as Righteous among the Nations for their efforts.

The Holocaust

For many centuries, Lithuania was one of the great centers of Jewish theology, philosophy, and learning, symbolized by the renowned teachings of the Vilna Gaon. After the First World War, the territory of the new Republic of Lithuania did not include the Vilnius/Vilna region, which was occupied by Poland. Before the Holocaust, the Republic of Lithuania was home to 160,000 Jews. At the beginning of World War II, the Soviets annexed the eastern portion of Poland, including the Vilnius/Vilna region, and in 1940, upon annexing Lithuania, the Soviets transferred the Vilnius/Vilna region to Lithuania. As a result of this enlargement of the territory of Lithuania (and some influx of Jewish refugees from other portions of Poland), by 1941 the Jewish population of Lithuania was approximately 250,000. There was some Lithuanian involvement in the Holocaust, as Nazis encouraged pogroms against the Jewish population after the German invasion, which began on the night of June 21-22, 1941. In the days before the Germans imposed effective administrative control, Lithuanian nationalist paramilitary forces began to massacre Jewish civilians. According to German documentation, between the 25th and 26th of June, 1941, "about 1,500 Jews were eliminated by the Lithuanian partisans. Many Jewish synagogues were set on fire; on the following nights of 25th and 26th of June another 2,300 were killed."[11]

Between June and July 1941, detachments of German Einsatzgruppe A, together with Lithuanian auxiliaries, started large scale mass shootings of Jews, and by November 1941, many had been killed in places like Paneriai (Ponary massacre). The official German army report (“the Jager Report”) methodically lists for each Lithuanian town and village the number of men, women, and children who were systematically murdered by the joint forces of the SS and the Lithaunian paramilitary. http://www.remember.org/docss.html. Typically, the victims were murdered just outside of the communities in which they lived. A minority of the Jews were temporarily kept alive to provide slave labor. Approximately 40,000 Jews were concentrated in the Vilnius, Kaunas, Šiauliai, and Švenčionys ghettos, and in concentration camps, where they were given harsh work assignments and provided inadequate quantities of food. As a result, many died of starvation or disease over the next two years. In 1943, the ghettos were either destroyed by the Germans or turned into concentration camps, and 5,000 Jews were sent to the extermination camps. At the end of the war, only 10% of Lithuania's Jews survived.

- See also: Chiune Sugihara

Return of Soviet authority

In the summer of 1944, the Red Army reached eastern Lithuania, while the city of Vilnius was captured by the Home Army during the ill-fated Operation Ostra Brama. By January 1945, the Russians captured Klaipėda, on the Baltic coast. The USSR re-occupied Lithuania as a Soviet republic, with the passive agreement of the United States and Britain (see Yalta Conference and Potsdam Agreements).

- See also: Resistance in Lithuania during World War II

Soviet Lithuania (1944–1990)

Stalinism

The mass deportation campaigns of 1941–52 exiled 29,923 families to Siberia and other remote parts of the Soviet Union. Official statistics state that more than 120,000 people were deported from Lithuania during this period, while researchers estimate the number of political prisoners and deportees at 300,000. In response to these events, an estimated several tens of thousands of resistance fighters participated in unsuccessful partisan warfare against the Soviet regime from 1944. The last partisan was killed in combat in 1965. Soviet authorities encouraged immigration of non-Lithuanian workers, especially Russians, as a way of integrating Lithuania into the Soviet Union and to encourage industrial development. This period has a dedicated Grūtas Park.

- See also: Forest Brothers

Rebirth (1988–1990)

Until mid-1988, all political, economic, and cultural life was controlled by the Lithuanian Communist Party (LCP). Lithuanians as well as people in two other Baltic republics distrusted the Soviet regime even more than people in other regions of the Soviet state, and gave their own specific and active support to Gorbachev's program of social and political reforms by Lithuanians. Under the leadership of intellectuals, the Lithuanian reform movement "Lietuvos persitvarkymo sąjūdis" (the Reform Movement of Lithuania) was formed in mid1988 and declared a program of democratic and national rights, winning nationwide popularity. Inspired by Sąjūdis, the Lithuanian Supreme Soviet passed constitutional amendments on the supremacy of Lithuanian laws over Soviet legislation, annulled the 1940 decisions on proclaiming Lithuania a part of the USSR, legalized a multi-party system, and adopted a number of other important decisions, including the return of the national state symbols — the flag and the anthem. A large number of LCP members also supported the ideas of Sąjūdis, and with Sąjūdis support, Algirdas Brazauskas was elected First Secretary of the Central Committee of the LCP in 1988. On 23 August, 1989, 50 years after Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, in order to draw the world's attention to the fate of the Baltic nations, Latvians, Lithuanians and Estonians joined hands in a human chain that stretched 600 kilometres from Tallinn, to Rīga, to Vilnius. That human chain was called the Baltic Way. In December 1989, the Brazauskas-led LCP declared its independence from the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and became a separate party, which after it renamed itself in 1990 the Democratic Labour Party of Lithuania.

Independent modern Lithuania (1990–continuing)

Struggle for independence (1990–1991)

In 1990, Sąjūdis-backed candidates won the elections to the Lithuanian Supreme Soviet. On March 11, 1990, the Supreme Soviet (or, more precisely, the Supreme Council of Lithuania) proclaimed the restitution of Lithuanian independence, becoming the first of the Soviet republics to declare national rights. The Supreme Council of Lithuania also appointed leaders of the state and adopted the Provisional Fundamental Law (temporary constitution) on this day and the Lithuanian SSR ceased to exist. Vytautas Landsbergis became the head of the state and Kazimira Prunskienė led the Cabinet of Ministers..

On March 15 the Soviet Union demanded revocation of the act and began employing political and economic sanctions against Lithuania. Soviet military was used to seize a couple of public buildings. Also, it showed its force by driving its tanks through the streets of Vilnius. The Lithuanians, inspired by their government, protested against Soviet actions in a non-violent manner.

On January 10, 1991, Soviet authorities seized the main publishing house and other premises in Vilnius and attempted to suppress the elected government by sponsoring a so called "National Salvation Committee". Three days later, during the January Events, the Soviets forcibly took over the Vilnius TV Tower, killing 14 unarmed civilians and injuring 700. The self-styled National Salvation Committee declared the Government overthrown, but capturing of houses of the Supreme Council and the Government never followed. Moscow failed to act further to crush the Lithuanian independence movement in light of widespread world criticism and a dearth of local popular support. The Lithuanian government continued to work.

During the national plebiscite on February 9 more than 90% of those who took part in the voting (and 76% of all eligible voters) voted in favor of an independent, democratic Lithuania. Led by tenacious Vytautas Landsbergis, Lithuanian leadership continued to labor for Western diplomatic recognition of its independence.

The Soviet Foreign Ministry had called the validity of that and other Lithuanian elections of the time into question, particularly given the strong support that Algirdas Brazauskas commanded in the Seimas. Meanwhile, Soviet military and security forces continued forced conscription, occasional seizure of buildings, attacks on customs posts, and a few killings of customs and police officials.

Recognition of independence, 1991

During the 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt, Soviet military troops took over several communications and other government facilities in Vilnius and other cities, but returned to their barracks when the coup failed. The Lithuanian Government banned the Communist Party and ordered confiscation of its property. Independence was first recognised by Iceland and finally recognized by Russia in September 1991, several months after the referendum.

Building the new state (1991–1996)

Political developments

As in many other formerly Soviet countries, popularity of the liberating movement (Sąjūdis in this case) was diminishing, due to people's overly high expectations that the country would immediately become rich when it became capitalist, which understandably did not happen. Due to the change towards a market economy some indicators, e.g., employment (which was near 100% during Soviet times due to underemployment), fell. At the time the Lithuanian Communist Party renamed itself Democratic Labour Party of Lithuania (LDDP) and ran against Sąjūdis in 1992 elections. Sąjūdis failed at those elections, and LDDP won the majority, although the did not have enough power to change the constitution. This was not expected, and LDDP had even less candidates in their lists than they got seats in parliament, therefore, according to the law, the unused seats were distributed among other political parties according to the percentages of votes. LDDP did not go the radical way back as, for example, the Belarusians did, and more or less continued building the independent state. Leftist policies however also proved to be wrong for the time, and in the elections of 1996 rightist Homeland Union won the majority of seats. Homeland Union has been established by Vytautas Landsbergis, leader of Sąjūdis, when it was seen that Sąjūdis needed reform. Sąjūdis remained as a public organisation, slowly diminishing and losing its importance. Although it exists today, it is not involved in politics any longer.

Privatization

It was decided that the state would have a market economy and therefore organizations like shops and flats, which were owned by government and leased to people, were to be privatised. Because people did not have money, the government issued investment vouchers of varying amounts to everybody, which could be used to privatise things such as real estate. Privatisation of companies was performed in auctions where the one who could offer the most cheques would win. People cooperated in groups to have a larger amount to offer and the privatisation campaign in Lithuania, unlike Russia, did not create a small group of very wealthy and powerful people. This was probably because the privatisation started with small organizations, and not large enterprises such as telecoms or airlines, which were done much later and some are still left unprivatised (and then already a monetary model was chosen for privatisation instead of a cheque-based one).

Privatisation however created a problem by people who were new to business acquiring some factories which were thriving previously and being unable to make them continue prospering. Others claim however that the fate of these factories was already sealed anyway because they were uneconomical and could only have been working under the planned economy of the Soviet Union.

Russian troop withdrawal (1991–1994)

Despite Lithuania's achievement of complete independence, sizable numbers of Russian forces remained in its territory. Withdrawal of those forces was one of Lithuania's top foreign policy priorities. Lithuania and Russia signed an agreement on September 8, 1992, calling for Russian troop withdrawals by August 31, 1993, which took place on time.

Forming the military

The first military of the reborn country were the Lithuanian volunteers, who first took an oath at the Supreme Council of Lithuania soon after the independence declaration. Later SKAT was formed from them. However, when the LDDP (former communists) came to power in 1992, the position of the volunteers was weakened, according to them on purpose, by not giving them enough weaponry, financing nor uniforms. This led to the Coup of the Volunteers, but with time the situation calmed down, and Lithuanian military built itself to the common standard with an air force, navy and land army. SKAT remained too, and interwar paramilitary organisations such as Lithuanian Riflemen's Union, Young Riflemen, and Lithuanian Scouts were re-created. However, riflemen's organisations do not have the power or support they enjoyed in interwar Lithuania.

Forming the monetary system

Lithuania's monetary system was to be based on Litas, the currency used during the interwar republic of Lithuania. The name Litas derives from the name Lithuania (the other Baltic State, Latvia, has similarly-named currency Lats). The currency was to be introduced quickly, immediately after Russian ruble, however it did not happen and Russia did not support the use of Roubles in Lithuania. Therefore a temporary currency, talonas, was introduced (commonly called Vagnorkė or Vagnorėlis because Gediminas Vagnorius was prime minister during its introduction). This currency however was very simple, easily counterfeited, and also was subject to heavy inflation. There were two versions of talonas, a large note and then a small note, the smaller notes were being released to change the large banknotes when they lost their value, but it was later controversially decided that the large banknotes would regain value again.

Eventually Litas was issued (printed outside Lithuania), and it was decided to peg it to the United States dollar and later to the Euro. Some possible affairs and conspiracy theories exist about the issue of litas. Since then except for the first few years and up until joining the European Union, inflation in Lithuania has been among the lowest in Europe.

Lithuania in the European Union (2004-present)

In October 2002, Lithuania was invited to join the European Union (EU) and one month later to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO); it became a member of both in 2004. The Lithuanian Military began a programme of modernisation and integration with NATO forces.[12] It has been noted that since Lithuania joined the EU there has been significant emigration to both the UK and Ireland.

See also

- Baltic region

- Republic of Central Lithuania

- Forest Brothers

- History of Vilnius

- History of Poland

- Lithuania

- Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

- Russians in Lithuania

- Law of Lithuania

- Territorial changes of the Baltic states

Notes

- ↑ Edvardas Gudavičius. Lietuvos istorija. Nuo seniausių laikų iki 1569 metų, Vilnius, 1999, p.28. ISBN 5-420-00723-1

- ↑ R. Bideleux. A History of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change. Routledge, 1998. p.122

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Hiden, John and Salmon, Patrick. The Baltic Nations and Europe. London: Longman. 1994.

- ↑ (Lithuanian) Maksimaitis, Mindaugas (2005). Lietuvos valstybės konstitucijų istorija (XX a. pirmoji pusė). Vilnius: Justitia. pp. 35–36. ISBN 9955-616-09-1.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Eidintas, Alfonsas; Vytautas Žalys, Alfred Erich Senn (September 1999). "Chapter 1: Restoration of the State". in Ed. Edvardas Tuskenis. Lithuania in European Politics: The Years of the First Republic, 1918-1940 (Paperback ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 20–28. ISBN 0-312-22458-3.

- ↑ Vardys, Vytas Stanley; Judith B. Sedaitis (1997). Lithuania: The Rebel Nation. Westview Series on the Post-Soviet Republics. WestviewPress. pp. 34–36. ISBN 0-8133-1839-4.

- ↑ (Lithuanian) Audronė Janavičienė. Sovietiniai diversantai Lietuvoje (1941–1944) at Genocid.lt

- ↑ US DoJ.

- ↑ Vill.

- ↑ World War II in the Baltic, Mike Hurtado, May 23, 2002 in Encyclopedia of Baltic History - a research project by undergraduate and graduate students at the University of Washington

- ↑ Einsatzgruppen Archives.

- ↑ Biuletenis A4 SP.p65

Bibliography

- Zigmantas Kiaupa, et al. The History of Lithuania Before 1795 (Vilnius: Lithuanian Institute of History, 2000).

External links

- Pages and Forums on the Lithuanian History

- Zenonas Langaitis virtual Old Radio museum — Old Radios from Lithuania,Europa,past USSR.

|

||||||||||||||||||||