Historic counties of England

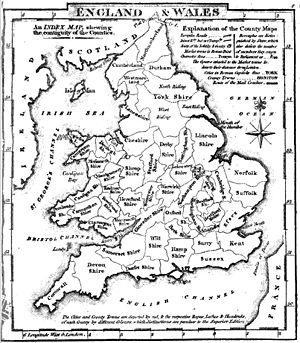

The historic counties of England are ancient subdivisions of England.[1] They were used for various functions for several hundred years[2] and continue to form, albeit with considerably altered boundaries, the basis of modern local government.[3][4] They are alternatively known as ancient counties.[5]

Contents |

The counties

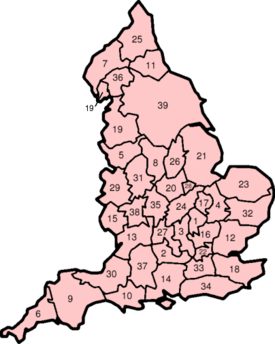

The historic counties are as follows:[6]

|

|

* = county palatine |

The map omits all exclaves (detached parts) apart from the Furness part of Lancashire south of Cumberland and Westmorland. Monmouthshire, although often historically regarded as an English county, is also not shown. The county was created out of ‘the said Country or Dominion of Wales’ by the Laws in Wales Act of 1535. It was later added to the Oxford circuit of the English Assizes, leaving its status ambiguous until 1974. However, every law relating to Wales alone since 1536 has included Monmouthshire as part of Wales[7]and for most legal purposes it has been regarded as part of Wales[8]. Although considered to be a county of England for parliamentary purposes until 1950 and administrative purposes until 1974, it is now administered as part of Wales.[9]

Naming and abbreviations

Counties named after towns were often legally known as "the County of" followed by the name of the town — Yorkshire was referred to as "the County of York", for example. This usage was sometimes followed even where there was no town by that name, such as "the County of Berks". The modern usage is to use the suffix "-shire" only for counties named after towns and for those that would otherwise have only one syllable. Kent was a former kingdom of the Jutes, so "Kentshire" was never used.

The name of County Durham is anomalous. The expected form would be "Durhamshire", but it has never been used. This is ascribed to that county's history as a county palatine ruled by the Bishop of Durham.

In the past, usages such as "Devonshire", "Dorsetshire" and "Somersetshire" were frequent.[10] There is still a Duke of Devonshire, who is not properly called the Duke of Devon.

There are customary abbreviations for many of the counties. In most cases these consist of simple truncation, usually with an "s" at the end, such as "Berks" for Berkshire or "Bucks" for Buckinghamshire. Some abbreviations are not obvious, such as "Salop" for Shropshire, "Oxon" for Oxfordshire, "Hants" for Hampshire and "Northants" for Northamptonshire.

Area

Accurate measurements of the areas of counties were not available until the 19th century, as a by-product of the Ordnance Survey's boundary survey. The officially recorded areas were adjusted to match the new data at the time of the 1861 Census, replacing the less reliable figures previously used by the Registrar General.[11]

For a list of the historic counties by their area, see:

- List of counties of England by area in 1815

- List of counties of England by area in 1831

- List of ancient counties of England by area in 1891

Origins

The establishment of counties had begun by the 12th century, although many boundaries date from far earlier, incorporating Saxon and Celtic divisions. However, some borders did not assume their commonly recognised forms until considerably later, in some cases the 16th century. Because of their differing origins the counties varied considerably in size. The county boundaries were fairly static between the 16th century Laws in Wales acts and the Local Government Act 1888.[12]

In most cases the counties or shires in medieval times were administered by a sheriff (originally "shire-reeve") on behalf of the monarch. Each shire was rsponsible for gathering taxes for the central government; for local defence; and for justice, through assize courts.[13]

Southern England

In southern England the counties were mostly subdivisions of the Kingdom of Wessex, and in many areas represented annexed, previously independent, kingdoms or other tribal territories. Kent derives from the Kingdom of Kent, and Essex, Sussex and Middlesex come from the East Saxons, South Saxons and Middle Saxons. Norfolk and Suffolk were subdivisions representing the "North Folk" and "South Folk" of the Kingdom of East Anglia. Only one county on the south coast of England now usually takes the suffix "-shire", Hampshire, which is named after the former town of "Hamwic" (sic), the site of which is now a part of the city of Southampton. Devon and Cornwall were based on the pre-Saxon Celtic kingdoms known in Latin as Dumnonia and Cornubia.

The City of London was recognised as a county of itself separate from Middlesex by Henry I's charter of c.1131.[14] A number of other boroughs in the area were constituted counties corporate by royal charter. Bristol developed as a major port in the mediæval period, straddling both sides of the River Avon which formed the ancient boundary between Gloucestershire and Somerset. In 1373, Edward III decreed

…that the said town of Bristol with its suburbs and their precinct, as the boundaries now exist, henceforward shall be separated and exempt in every way from the said counties of Gloucester and Somerset, on land and by water; that it shall be a county in itself and be called the county of Bristol for ever…[15]

Similar arrangements were later applied to Norwich (1404), Southampton (1447), Canterbury (1471), Gloucester (1483), Exeter (1537), and Poole (1571).[16]

Midlands

When Wessex conquered Mercia in the 9th and 10th centuries, it subdivided the area into various shires of roughly equal size and tax-raising potential or hidage. These generally took the name of the main town (the county town) of the county, along with "-shire". Examples of these include Northamptonshire and Warwickshire. In some cases the original names have been worn down — for example, Cheshire was originally "Chestershire".[17]

In the east Midlands, it is thought that county boundaries may represent a 9th century division of the Danelaw between units of the Danish army.[13] Rutland was an anomalous territory or Soke, associated with Nottinghamshire, but it eventually became considered the smallest county. Lincolnshire was the successor to the Kingdom of Lindsey, and took on the territories of Kesteven and Holland when Stamford became the only Danelaw borough to fail to become a county town.[18]

Charters were granted constituting the boroughs or cities of Lincoln (1409), Nottingham (1448), Lichfield (1556) and Worcester (1622) as counties. The County of the City of Coventry was separated from Warwickshire in 1451, and included an extensive area of countryside surrounding the city.[19]

The border with Wales was not set until the Laws in Wales Act 1535 — this remains the modern border. At the time of the Domesday Book, the border counties included parts of what later became Wales. Monmouth, for example, was included in Herefordshire.[20] The ancient town of Ludlow, now in Shropshire, was included in Herefordshire in the Domesday Book. Parts of the March of Wales which after the Norman conquest had been administered by Marcher Lords largely independently of the English monarch, were incorporated into the English counties of Shropshire, Herefordshire and Gloucestershire in 1535.

Northern England

Much of Northumbria was also shired, the best known of these counties being Hallamshire and Cravenshire. The Normans did not use these divisions, and so they are not generally regarded as historic counties. The huge county of Yorkshire was a successor to the Viking Kingdom of York, and at the time of the Domesday Book in 1086 it was considered to include what was to become northern Lancashire, as well as parts of Cumberland, and Westmorland. Most of the later Cumberland and Westmorland were under Scottish rule until 1092. After the Norman Conquest in 1066 and the harrying of the North, much of the North of England was left depopulated and was included in the returns for Cheshire and Yorkshire in the Domesday Book.[21] However, there is some disagreement about the status of some of this land. The area in between the River Ribble and the River Mersey, referred to as "Inter Ripam et Mersham" in the Domesday Book,[22] was included in the returns for Cheshire,[23] but recent sources report that this did not mean that this land was actually part of Cheshire.[24][25][26][27] though one source implies that it was.[22] The Northeast, or Northumbria, land that later became County Durham and Northumberland, was left unrecorded.

Cumberland, Westmorland, Lancashire, County Durham and Northumberland were established as counties in the 12th century. Lancashire can be firmly dated to 1182.[28] Part of the domain of the Bishops of Durham, Hexhamshire was split off and was considered an independent county until 1572, when it became part of Northumberland.

Charters granting separate county status to the cities and boroughs of Chester (1238/9), York (1396), Newcastle upon Tyne (1400) and Kingston-upon-Hull (with the surrounding area of Hullshire) (1440). In 1551 Berwick upon Tweed, on the border with Scotland, was created a county corporate.

Role

By the late Middle Ages the county was being used as the basis of a number of functions.[2]

Administration of justice and law enforcement

The Assize Courts used counties, or their major divisions, as a basis for their organisation.[3] Justices of the peace originating in Norman times as Knights of the Peace,[29] were appointed in each county. At the head of the legal hierarchy were the High Sheriff and the Custos rotulorum (keeper of the rolls) for each county.

Until the 19th century law enforcement was mostly carried out at the parish level. With an increasingly mobile population, however, the system became outdated. Following the successful establishment of the Metropolitan Police in London, the County Police Act 1839 empowered justices of the peace to form county constabularies outside boroughs. The formation of county police forces was made compulsory by the County and Borough Police Act 1856.

Defence

In the 1540s the office of Lord Lieutenant was instituted. The lieutenants had a military role, previously exercised by the sheriffs, and were made responsible for raising and organising the militia in each county. The lieutenancies were subsequently given responsibility for the Volunteer Force. In 1871 the lieutenants lost their positions as heads of the militia, and their office became largely ceremonial.[30] The Cardwell and Childers Reforms of the British Army linked the recruiting areas of infantry regiments to the counties.

Parliamentary representation

Each county sent two Knights of the Shire to the House of Commons (in addition to the burgesses sent by boroughs). Yorkshire gained two members in 1821 when Grampound was disenfranchised. The Great Reform Act of 1832 reapportioned members throughout the counties, many of which were also split into parliamentary divisions. Constituencies based on the historic county boundaries remained in use until 1918.

Local government

From the 16th century onwards the county was increasingly used as a unit of local government as the justices of the peace took on various administrative functions known as "county business". This was transacted at the quarter sessions, summoned four times a year by the lord lieutenant. By the 19th century the county magistrates were exercising powers over the licensing of alehouses, the construction of bridges, prisons and asylums, the superintendence of main roads, public buildings and charitable institutions, and the regulation of weights and measures.[31] The justices were empowered to levy local taxes to support these activities, and in 1739 these were unified as a single "county rate", under the control of a county treasurer.[32] In order to build and maintain roads and bridges, a salaried county surveyor was to be appointed.[33]

By the 1880s it was being suggested that it would be more efficient if a wider variety of functions were provided on a county-wide basis.[34]

Subdivisions

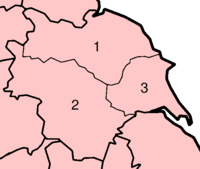

- North Riding

- West Riding

- East Riding

Some of the counties had major subdivisions. Of these, the most significant were the divisions of Yorkshire: the East Riding, West Riding, North Riding and the ainsty of York. Since Yorkshire is so big, its ridings became established as geographical terms quite apart from their original role as administrative divisions. The second largest county, Lincolnshire, was divided into three historic "parts" (intermediate in size between county and wapentake): Lindsey, Holland and Kesteven. Other divisions include those of Sussex into East Sussex and West Sussex, and, more informally and hence more vaguely, of Kent into East Kent and West Kent.

Several counties had liberties or Sokes within them that were administered separately. Cambridgeshire had the Isle of Ely, and Northamptonshire had the Soke of Peterborough. Such divisions were used by such entities as the Quarter Sessions courts and were inherited by the later administrative county areas under the control of county councils.

Most English counties were subdivided into smaller subdivisions called hundreds. Nottinghamshire, Yorkshire and Lincolnshire were divided into wapentakes (a unit of Danish origin), while Durham, Northumberland, Cumberland and Westmorland were divided into wards, areas originally organised for military purposes, each centred on a castle.[35] Kent and Sussex had an intermediate level between their major subdivisions and their hundreds, known as lathes in Kent and rapes in Sussex. Hundreds or their equivalents were divided into tithings and parishes (the only class of these divisions still used administratively), which in turn were divided into townships and manors. In the 17th century the Ossulstone hundred of Middlesex was further divided into four divisions, which replaced the functions of the hundred. The borough and parish were the principal providers of local services throughout England until the creation of ad-hoc boards and, later, local government districts.

Change

Detached parts

The historic counties had many anomalies, and many small exclaves, where a parcel of land was politically part of one county despite not being physically connected to the rest of the county. The Counties (Detached Parts) Act 1844 modified the counties by abolishing the many enclaves of counties within others, which had already been done for Parliamentary purposes by the Great Reform Act.

Large exclaves affected by the 1844 Act included the County Durham exclaves of Islandshire, Bedlingtonshire and Norhamshire, which were incorporated into Northumberland; and the Halesowen exclave of Shropshire, which was incorporated into Worcestershire.

Exclaves that the 1844 Act did not touch include the part of Derbyshire around Donisthorpe, locally in Leicestershire; and most of the larger exclaves of Worcestershire, including the town of Dudley, which remained surrounded by Staffordshire. Additionally, the Furness portion of Lancashire remained separated from the rest of Lancashire by a narrow strip of Westmorland — though it was accessible by way of the Morecambe Bay tidal flats.

1889

When the first county councils were set up in 1889, they covered newly created entities known as administrative counties; which consisted of counties less independent areas known as county boroughs. Several historic subdivisions with separate county administrations were also created administrative counties, particularly the separate ridings of Yorkshire, the separate parts of Lincolnshire, and East and West Sussex..[36] The Local Government Act 1888 also contained wording to create both a new "administrative county" and "county" of London,[37] and to ensure that the statutory "counties" consisted of agglomerations of administrative counties and county boroughs. These counties were to be used "for all purposes, whether sheriff, lieutenant, custos rotulorum, justices, militia, coroner, or other". In retrospect, these statutory counties can be identified as the predecessors of the ceremonial counties of England. These counties are the ones usually shown on maps of the early to mid-20th century, and they largely displaced the historic counties in such uses. The censuses of 1891, 1901 and 1911 provided figures for the "ancient counties".

Several towns are historically divided between counties, including Banbury, Burton upon Trent, Newmarket, Peterborough, Royston, Stamford, Tamworth, Todmorden and Warrington. In Newmarket and Tamworth the county boundary ran right up the middle of the high street, and in Todmorden the boundary is said to run through the town hall. The 1888 Act ensured that every urban sanitary district would be considered to be part of a single county. This principle was maintained in the 20th century: when county boroughs such as Birmingham, Manchester, Reading, Sheffield and Stockport expanded into neighbouring counties, the area added became associated with another county.

1965 and 1974

On April 1, 1965 a number of changes came into effect. The new administrative area of Greater London was created, resulting in the abolition of the counties of London and Middlesex, at the same time taking in areas from surrounding counties. On the same date the new counties of Cambridgeshire and Isle of Ely and of Huntingdon and Peterborough were formed by the merger of pairs of administrative counties. The new areas were also adopted for lieutenancy and shrievalty purposes.

In 1974 a major local government reform took place under the Local Government Act 1972. The Act abolished administrative counties and county boroughs, and divided England (except Greater London and the Isles of Scilly) into counties. These were of two types: "metropolitan" and "non-metropolitan" counties.[38] [39] Apart from local government, the new counties were "substituted for counties of any other description" for judicial, shrievalty, lieutenancy and other purposes.[40] Several counties, such as Cumberland, Herefordshire, Rutland, Westmorland and Worcestershire, vanished from the administrative map, while new entities such as Avon, Cleveland, Cumbria and Humberside appeared, in addition to the six new metropolitan counties.[41]

The built-up areas of conurbations tend to cross historic county boundaries freely.[42] Examples here include Bournemouth–Poole–Christchurch (Dorset and Hampshire) Greater Manchester (Cheshire, Lancashire and Yorkshire), Merseyside (Cheshire and Lancashire), Teesside (Yorkshire and County Durham), South Yorkshire (Yorkshire, Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire), Tyneside (County Durham and Northumberland) and West Midlands (Shropshire, Staffordshire, Warwickshire and Worcestershire). Greater London itself straddles five historic counties — Essex, Hertfordshire, Kent, Middlesex, Surrey — and the London urban area sprawls into Buckinghamshire and Berkshire. The Local Government Act 1972 sought generally to unite conurbations within a single county, while retaining the historic county boundaries as far as was practicable.[4]

Postal counties

In a period of financial crisis,[43] the Post Office was able to alter many of its postal counties in accordance with the 1965 and 1974 reforms, but not all. The two major exceptions were Greater London and Greater Manchester. Greater London was not adopted in 1965, since, according to the Post Office at the time, it would have been too expensive to do so, while it gave as its reason for not adopting Greater Manchester the ambiguity of the name with the Manchester post town. Perhaps as a result of this, the historic counties appear not to have fallen completely out of use for locating places in Greater Manchester, along with areas of Greater London that are not part of the London postal district. It is common for people to speak of Uxbridge, Middlesex, or Bromley, Kent (which are outside of the London postal district), but much less so to speak of Brixton, Surrey, Greenwich, Kent, or West Ham, Essex (which are inside it).

In 1996, following further local government reform and the modernisation of its sorting equipment, the Royal Mail ceased to use counties at all in the direction of mail[44]. Instead it now uses the outward code (first half) of the postcode. The former postal counties were removed in 2000 from its Postcode Address File database and included in an "alias file",[45] which is used to cross-references details that may be added by users but are no longer required, such as former street names or historic, administrative and former postal counties.

Restoration of historic county boundaries

A review of the structure of local government in England by the Local Government Commission for England led to the restoration of the East Riding of Yorkshire, Herefordshire, Rutland and Worcestershire as administrative areas in the 1990s; the abolition of Avon, Cleveland and Humberside within 25 years of their creation;, and the restoration of the traditional borders between Somerset and Gloucestershire, Durham and Yorkshire (towards the mouth of the River Tees; not in Teesdale), and Yorkshire and Lincolnshire for ceremonial purposes in these areas. The case of Huntingdonshire was considered twice, but the Commission found that "there was no exceptional county allegiance to Huntingdonshire, as had been perceived in Rutland and Herefordshire".[46]

The Association of British Counties, and its regional affiliates, such as the Friends of Real Lancashire and the Yorkshire Ridings Society,[47][48] are pressure groups that assert that, on the basis that they were not formally abolished, the counties continue to exist with their ancient boundaries. These groups seek to promote greater public awareness of what they term "traditional counties" and broadly wish to see counties realigned to the historic boundaries.

A direct action group, CountyWatch, was formed in 2004 to remove what its members consider to be wrongly placed county boundary signs that do not mark the historic or traditional county boundaries of England and Wales. They have removed, resorted or erected a number of what they claim to be "wrongly sited" county boundary signs in various parts of England. For instance, in Lancashire 30 signs were removed[49]. CountyWatch has been criticised for such actions by the councils that erected the signs: [50] in Lancashire the county council pointed out that the taxpayers would have to pay for the signs to be re-erected.[51]

The only political party with a manifesto commitment to restore the boundaries and political functions of all historic counties, including Middlesex and Monmouthshire, is the English Democrats Party.[52]

Vice counties

The vice counties, used for biological recording since 1852, are largely based on historic county boundaries. They ignore all exclaves and are modified by subdividing large counties and merging smaller areas into neighbouring counties; such as Rutland with Leicestershire and Furness with Westmorland. The static boundaries make Longitudinal study of biodiversity easier. They also cover the rest of Great Britain and Ireland.

Current use

As of 2008, the historic counties continue to form, with considerably altered boundaries, many of the ceremonial and non-metropolitan counties in England.

| Retained | Bedfordshire, Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, Cambridgeshire, Cheshire, Cornwall, Derbyshire, Devon, Dorset, Durham, Essex, Gloucestershire, Hampshire, Hertfordshire, Kent, Lancashire, Leicestershire, Lincolnshire, Norfolk, Northamptonshire, Northumberland, Nottinghamshire, Oxfordshire, Shropshire, Somerset, Staffordshire, Suffolk, Surrey, Warwickshire, Wiltshire |

|---|---|

| Abandoned and later revived | Herefordshire, Rutland, Worcestershire |

| Abandoned | Cumberland, Huntingdonshire, Middlesex, Sussex†, Westmorland, Yorkshire† |

†The contemporary counties continue to use the historic county names with a prefix (such as East Sussex and North Yorkshire).

Notes and references

- ↑ Thomson, D., England in the Nineteenth Century (1815–1914), (1978)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Bryne, T., Local Government in Britain, (1994)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Her Majesty's Stationary Office, Aspects of Britain: Local Government, (1996)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Hampton, W., Local Government and Urban Politics, (1991)

- ↑ Vision of Britain — Type details for ancient county. Retrieved 19 October 2006.

- ↑ Vision of Britain — List of subdivisions of England. Retrieved 19 October 2006.

- ↑ 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Reader's Digest (1965) Complete Atlas of the British Isles

- ↑ Representation of the People Act 1918, c.64; Representation of the People Act 1948, c.65; Local Government Act 1933, c.51; Local Government Act 1972, c.70

- ↑ The 1870s Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales used "Devonshire", "Dorsetshire" and Somerset" as headwords, also mentioning the Somersetshire usage. Retrieved 19 October 2006.

- ↑ David Fletcher, The Ordnance Survey's Nineteenth Century Boundary Survey: Context, Characteristics and Impact, Imago Mundi, Vol. 51. (1999), pp. 131-146.

- ↑ Vision of Britain — Census Geographies. Retrieved 19 October 2006.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Angus Winchester, Discovering Parish Boundaries, 1990, ISBN 0-7478-0470-2

- ↑ "Charter granted by Henry I to London". Florilegium Urbanum (2006). Retrieved on 25 November 2008.

- ↑ Text of Bristol Royal Charter of 1373

- ↑ The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, p.86

- ↑ Domesday Explorer — Early administrative units. Retrieved 19 October 2006.

- ↑ Stamford Visitor Information — Timeline. Retrieved 19 October 2006.

- ↑ "Creation of the County of the City". A History of the County of Warwick: Volume 8: The City of Coventry and Borough of Warwick. British History Online (1969). Retrieved on 25 November 2008.

- ↑ Domesday Book Online - Herefordshire. Retrieved 19 October 2006.

- ↑ Domesday Explorer — County definition. Retrieved 19 October 2006.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Sylvester (1980). p. 14.

- ↑ Morgan (1978). pp.269c–301c,d.

- ↑ Harris and Thacker (1987). write on page 252:

Certainly there were links between Cheshire and south Lancashire before 1000, when Wulfric Spot held lands in both territories. Wulfric's estates remained grouped together after his death, when they were left to his brother Ælfhelm, and indeed there still seems to have been some kind of connexion in 1086, when south Lancashire was surveyed together with Cheshire by the Domesday commissioners. Nevertheless, the two territories do seem to have been distinguished from one another in some way and it is not certain that the shire-moot and the reeves referred to in the south Lancashire section of Domesday were the Cheshire ones.

- ↑ Phillips and Phillips (2002). pp. 26–31.

- ↑ Crosby, A. (1996). writes on page 31:

The Domesday Survey (1086) included south Lancashire with Cheshire for convenience, but the Mersey, the name of which means 'boundary river' is known to have divided the kingdoms of Northumbria and Mercia and there is no doubt that this was the real boundary.

- ↑ This means that the map given in this article which depicts the counties at the time of the Domesday Book is misleading in this respect.

- ↑ George, D., Lancashire, (1991)

- ↑ Elcock, H, Local Government, (1994)

- ↑ Regulation of Forces Act 1871

- ↑ Carl H. E. Zangerl (November 1971), "The Social Composition of the County Magistracy in England and Wales, 1831–1887", The Journal of British Studies 11(1):113–25.

- ↑ An Act for the more easy assessing, collecting and levying of County Rates, (12 Geo.II c. 29)

- ↑ Bridges Act 1803 (1803 c. 59) and Grand Jury Act 1833 (1833 c. 78)

- ↑ Kingdom, J., Local Government and Politics in Britain, (1991)

- ↑ W. L. Warren, The Myth of Norman Administrative Efficiency: The Prothero Lecture in Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 5th Ser., Vol. 34. (1984), p. 125

- ↑ Redcliffe-Maud & Wood, B., English Local Government Reformed, (1974)

- ↑ Barlow, I., Metropolitan Government, (1991)

- ↑ Local Government Act 1972 (1972 c.70), s.1)

- ↑ Arnold-Baker, C., Local Government Act 1972, (1973)

- ↑ Local Government Act 1972 (1972 c.70), s. 216

- ↑ Jones, B. et al, Politics UK, (2004)

- ↑ Dearlove, J., The reorganisation of British local government, (1979)

- ↑ Corby, M. The postal business, 1969–79, (1979)

- ↑ Royal Mail, Address Management Guide, (2004)

- ↑ Royal Mail, PAF Digest, (2003)

- ↑ Local Government Commission for England. Final Recommendations on the Future Local Government of: Basildon & Thurrock, Blackburn & Blackpool, Broxtowe, Gedling & Rushcliffe, Dartford & Gravesham, Gillingham & Rochester Upon Medway, Exeter, Gloucester, Halton & Warrington, Huntingdonshire & Peterborough, Northampton, Norwich, Spelthorne and the Wrekin. December 1995.

- ↑ Lancastrians' pride in heritage, BBC News Online 27 November, 2004. Retrieved 19 October 2006.

- ↑ White rose county has its day, BBC News Online July 21, 2003. Retrieved 19 October 2006.

- ↑ "County signs dumped after protest", BBC News Online (2002-11-15). Retrieved on 2007-08-05.

- ↑ Wood, Alexandra (2005-09-23). "Protest group seizes the day in boundary row", Yorkshire Post. Retrieved on 2007-08-05.

- ↑ "Boundary protest 'to be reported'", BBC News Online (2002-11-14). Retrieved on 2007-08-05.

- ↑ "Manifesto & Constitution of the English Democrats, p. 4" (PDF). The English Democrats: Putting England First. The English Democrats Party (September 2006). Retrieved on 2007-08-09.

Bibliography

- Crosby, A. (1996). A History of Cheshire. (The Darwen County History Series.) Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Phillimore & Co. Ltd. ISBN 0850339324.

- Harris, B. E., and Thacker, A. T. (1987). The Victoria History of the County of Chester. (Volume 1: Physique, Prehistory, Roman, Anglo-Saxon, and Domesday). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0197227619.

- Morgan, P. (1978). Domesday Book Cheshire: Including Lancashire, Cumbria, and North Wales. Chichester, Sussex: Phillimore & Co. Ltd. ISBN 0850331404.

- Phillips A. D. M., and Phillips, C. B. (2002), A New Historical Atlas of Cheshire. Chester, UK: Cheshire County Council and Cheshire Community Council Publications Trust. ISBN 0904532461.

- Sylvester, D. (1980). A History of Cheshire. (The Darwen County History Series). (2nd Edition.) London and Chichester, Sussex: Phillimore & Co. Ltd. ISBN 0850333849.