Hindu-Arabic numeral system

| Numeral systems by culture | |

|---|---|

| Hindu-Arabic numerals | |

| Western Arabic Eastern Arabic Khmer |

Indian family Brahmi Thai |

| East Asian numerals | |

| Chinese Suzhou Counting rods |

Japanese Korean Mongolian |

| Alphabetic numerals | |

| Abjad Armenian Cyrillic Ge'ez |

Hebrew Greek (Ionian) Āryabhaṭa |

| Other systems | |

| Attic Babylonian Egyptian English |

Etruscan Mayan Roman Urnfield |

| List of numeral system topics | |

| Positional systems by base | |

| Decimal (10) | |

| 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64 | |

| 1, 3, 9, 12, 20, 24, 30, 36, 60, more… | |

The Hindu-Arabic numeral system is a positional decimal numeral system first documented in the ninth century. The system is based on ten, originally nine, different glyphs. The symbols (glyphs) used to represent the system are in principle independent of the system itself. The glyphs in actual use are descended from Indian Brahmi numerals, and have split into various typographical variants since the Middle Ages. These symbol sets can be divided into three main families: the West Arabic numerals used in the Maghreb and in Europe, the Eastern Arabic numerals used in Egypt and the Middle East, and the Indian numerals used in India.

Contents |

Positional notation

The Hindu-Arabic numeral system is designed for positional notation in a decimal system. In a more developed form, positional notation also uses a decimal marker (at first a mark over the ones digit but now more usually a decimal point or a decimal comma which separates the ones place from the tenths place), and also a symbol for "these digits recur ad infinitum". In modern usage, this latter symbol is usually a vinculum (a horizontal line placed over the repeating digits). In this more developed form, the numeral system can symbolize any rational number using only 13 symbols (the ten digits, decimal marker, vinculum or division sign, and an optional prepended dash to indicate a negative number).

Symbols

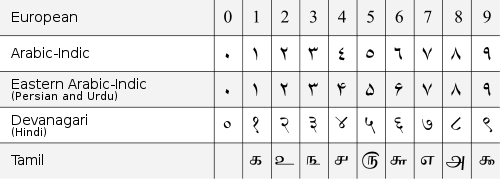

Various symbol sets are used to represent numbers in the Hindu-Arabic numeral, all of which evolved from the Brahmi numerals.

The symbols used to represent the system have split into various typographical variants since the Middle Ages:

- the widespread Western "Arabic numerals" used with the Latin, Cyrillic, and Greek alphabets in the table below labelled "European", descended from the "West Arabic numerals" which were developed in al-Andalus and the Maghreb (There are two typographic styles for rendering European numerals, known as lining figures and text figures).

- the "Arabic-Indic" or "Eastern Arabic numerals" used with the Arabic alphabet, developed primarily in what is now Iraq. A variant of the Eastern Arabic numerals used in Persian and Urdu.

- the "Devanagari numerals" used with Devanagari and related variants grouped as Indian numerals.

As in many numbering systems, the numbers 1, 2, and 3 represent simple tally marks. 1 being a single line, 2 being two lines (now connected by a diagonal) and 3 being three lines (now connected by two vertical lines). After three, numbers tend to become more complex symbols (examples are the Chinese/Japanese numbers and Roman numerals). Theorists believe that this is because it becomes difficult to instantaneously count objects past three.[1]

List of symbols in contemporary use

Note: Some symbols may not display correctly if your browser does not support Unicode fonts.

| Western Arabic | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Middle East Arabic | ٠ | ١ | ٢ | ٣ | ٤ | ٥ | ٦ | ٧ | ٨ | ٩ |

| Eastern Arabic | ۰ | ۱ | ۲ | ۳ | ۴ | ۵ | ۶ | ۷ | ۸ | ۹ |

| Devanagari | ० | १ | २ | ३ | ४ | ५ | ६ | ७ | ८ | ९ |

| Gujarati | ૦ | ૧ | ૨ | ૩ | ૪ | ૫ | ૬ | ૭ | ૮ | ૯ |

| Gurmukhi | ੦ | ੧ | ੨ | ੩ | ੪ | ੫ | ੬ | ੭ | ੮ | ੯ |

| Limbu | ᥆ | ᥇ | ᥈ | ᥉ | ᥊ | ᥋ | ᥌ | ᥍ | ᥎ | ᥏ |

| Assamese & Bengali | ০ | ১ | ২ | ৩ | ৪ | ৫ | ৬ | ৭ | ৮ | ৯ |

| Oriya | ୦ | ୧ | ୨ | ୩ | ୪ | ୫ | ୬ | ୭ | ୮ | ୯ |

| Telugu | ౦ | ౧ | ౨ | ౩ | ౪ | ౫ | ౬ | ౭ | ౮ | ౯ |

| Kannada | '೦ | ೧ | ೨ | ೩ | ೪ | ೫ | ೬ | ೭ | ೮ | ೯''''''' |

| Malayalam | ൦ | ൧ | ൨ | ൩ | ൪ | ൫ | ൬ | ൭ | ൮ | ൯ |

| Tamil (Grantha) | ೦ | ௧ | ௨ | ௩ | ௪ | ௫ | ௬ | ௭ | ௮ | ௯ |

| Tibetan | ༠ | ༡ | ༢ | ༣ | ༤ | ༥ | ༦ | ༧ | ༨ | ༩ |

| Burmese | ၀ | ၁ | ၂ | ၃ | ၄ | ၅ | ၆ | ၇ | ၈ | ၉ |

| Thai | ๐ | ๑ | ๒ | ๓ | ๔ | ๕ | ๖ | ๗ | ๘ | ๙ |

| Khmer | ០ | ១ | ២ | ៣ | ៤ | ៥ | ៦ | ៧ | ៨ | ៩ |

| Lao | ໐ | ໑ | ໒ | ໓ | ໔ | ໕ | ໖ | ໗ | ໘ | ໙ |

| Lepcha | ᱀ | ᱁ | ᱂ | ᱃ | ᱄ | ᱅ | ᱆ | ᱇ | ᱈ | ᱉ |

| Balinese | ᭐ | ᭑ | ᭒ | ᭓ | ᭔ | ᭕ | ᭖ | ᭗ | ᭘ | ᭙ |

| Sundanese | ᮰ | ᮱ | ᮲ | ᮳ | ᮴ | ᮵ | ᮶ | ᮷ | ᮸ | ᮹ |

| Ol Chiki | ᱐ | ᱑ | ᱒ | ᱓ | ᱔ | ᱕ | ᱖ | ᱗ | ᱘ | ᱙ |

| Osmanya | 𐒠 | 𐒡 | 𐒢 | 𐒣 | 𐒤 | 𐒥 | 𐒦 | 𐒧 | 𐒨 | 𐒩 |

| Saurashtra | ꣐ | ꣑ | ꣒ | ꣓ | ꣔ | ꣕ | ꣖ | ꣗ | ꣘ | ꣙ |

Note: Tamil zero is a modern innovation. Unicode 4.1 and later defines an encoding for it[2][3].

At present the following sets are being used:

These are the most widely-used symbols, used in western parts of the Arab world, west of Egypt, in European and Western countries and worldwide. They are known as Arabic numerals, Western numerals, European numerals or digits[1], Western Arabic numerals, Arabic Western numerals. In Arabic they are called "Western Numerals". (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9)

- Devanagari numerals

These symbols are used in languages that use the Devanagari script. (०, १, २, ३, ४, ५, ६, ७, ८, ९) They are sometimes called late Devanagari numerals to distinguish them from the early Devanagari numerals.

- Eastern Arabic numerals

In English they are also called Eastern Arabic numerals, Arabic-Indic numerals, Arabic Eastern Numerals. In Arabic though, they are called "Indian numerals", أرقام هندية, arqam hindiyyah. They are sometimes called Indic Numerals in English[2], however, this nomenclature is sometimes discouraged as it "leads to confusion with the digits currently used with the scripts of India"[3]. They are used in Egypt and Arabic countries east of it, and were also in the no longer used Ottoman Turkish script (٠.١.٢.٣.٤.٥.٦.٧.٨٩)

A variant of the Eastern Arabic numerals is used in Persian and Urdu* languages. (۰، ۱، ۲، ۳، ۴، ۵، ۶، ۷، ۸، ۹)

- For Urdu and other languages used by Muslims in India and Pakistan there is used the following Hindu-Arabic numeral system:

- Gurmukhi numerals

Used in the Punjabi language. (੦, ੧, ੨, ੩, ੪, ੫, ੬, ੭, ੮, ੯)

- Bengali numerals

Used in the Bengali and Assamese languages (০, ১, ২, ৩, ৪, ৫, ৬, ৭, ৮, ৯)

- Oriya numerals

Used in the Oriya language (୦, ୧, ୨, ୩, ୪, ୫, ୬, ୭, ୮, ୯)

- Tamil numerals

Used in the Tamil language (௦, ௧, ௨, ௩, ௪, ௫, ௬, ௭, ௮, ௯)

- Kannada numerals

Used in the Kannada language (೦, ೧, ೨, ೩, ೪, ೫, ೬, ೭, ೮, ೯)

- Malayalam numerals

Used in the Malayalam language (൦, ൧, ൨, ൩, ൪, ൫, ൬, ൭, ൮, ൯)

- Thai numerals

Used in the Thai language (๐, ๑, ๒, ๓, ๔, ๕, ๖, ๗, ๘, ๙)

- Tibetan numerals

Used in the Tibetan language (༠, ༡, ༢, ༣, ༤, ༥, ༦, ༧, ༨, ༩)

- Burmese numerals

Used in the Burmese language (၀, ၁, ၂, ၃, ၄, ၅, ၆, ၇, ၈, ၉)

- Eastern Cham numerals

- Western Cham numerals

- Khmer numerals

Used in Cambodia (០, ១, ២, ៣, ៤, ៥, ៦, ៧, ៨, ៩)

- Javanese numerals

Used in Java since the time of Pallavas. [6]

- Lepcha numerals

- Lao numerals

Used in Lao language (໐, ໑, ໒, ໓, ໔, ໕, ໖, ໗, ໘, ໙)

History

Origins

The Hindu-Arabic numeral system originated in India.[4] Graham Flegg (2002) dates the history of the Hindu-Arabic system to the Indus valley civilization.[4] The inscriptions on the edicts of Ashoka (1st millennium BCE) display this number system being used by the Imperial Mauryas.[4] This system was later transmitted to Europe by the Arabs.[4]

Buddhist inscriptions from around 300 BC use the symbols which became 1, 4 and 6. One century later, their use of the symbols which became 2, 4, 6, 7 and 9 was recorded. These Brahmi numerals are the ancestors of the Hindu-Arabic glyphs 1 to 9, but they were not used as a positional system with a zero, and there were rather separate numerals for each of the tens (10, 20, 30, etc.).

Positional notation without the use of zero (using an empty space in tabular arrangements, or the word kha "emptiness") is known to have been in use in India from the 6th century. The oldest known authentic document that may be argued to contain the use of zero and decimal notation is the Jaina cosmological text Lokavibhaga, which was completed on August 25, 458. [5]

The first inscription showing the use of zero which is dated and is not disputed by any historian is the inscription at Gwalior dated 933 in the Vikrama calendar (876 CE.) [8] [9].

This 9th century date is currently thought to be the first physical evidence for the use of positional zero in India. According to Lam Lay Yong,

- "the earliest appearance in India of a symbol for zero in the Hindu-Arabic numeral system is found in an inscription at Gwalior which is dated 876 AD".[10].

Professor EF Robertson and DR JJ O'Connor report:

- "The first record of the Indian use of zero which is dated and agreed by all to be genuine was written in 876" on the Gwalior tablet stone[11].

However, Arabic court records (see next section titled "Adoption by the Arabs") and the Persian mathematician Al-Khwarizmi's book On the Calculation with Hindu Numerals, clearly indicate that this system and the use of zero by the Indians predates 876 AD; with the aforementioned documents dated as 776 AD and 825 AD respectively.

According to Menninger (p. 400):

- "This long journey begins with the Indian inscription which contains the earliest true zero known thus far (Fig. 226). This famous text, inscribed on the wall of a small temple in the vicinity of Gvalior (near Lashkar in Central India) first gives the date 933 (A.D. 870 in our reckoning) in words and in Brahmi numerals. Then it goes on to list four gifts to a temple, including a tract of land "270 royal hastas long and 187 wide, for a flower-garden." Here, in the number 270 the zero first appears as a small circle [...]; in the twentieth line of the inscription it appears once more in the expression "50 wreaths of flowers" which the gardeners promise to give in perpetuity to honor the divinity."

The Encyclopaedia Britannica says, "Hindu literature gives evidence that the zero may have been known before the birth of Christ, but no inscription has been found with such a symbol before the 9th century."[12].

Adoption by the Arabs

These nine numerals were adopted by the Arabs in the 8th century. How the numbers came to the Arabs is recorded in al-Qifti's "Chronology of the scholars", which was written around the end the 12th century, quoting earlier sources [13]:

- ... a person from India presented himself before the Caliph al-Mansur in the year 776 who was well versed in the siddhanta method of calculation related to the movement of the heavenly bodies, and having ways of calculating equations based on the half-chord [essentially the sine] calculated in half-degrees ... Al-Mansur ordered this book to be translated into Arabic, and a work to be written, based on the translation, to give the Arabs a solid base for calculating the movements of the planets ...

This book presented by the Indian scholar was probably Brahmasphuta Siddhanta (The Opening of the Universe) which was written in 628 (Ifrah) [14] by the Indian mathematician Brahmagupta.

The numeral system came to be known to both the Persian mathematician Al-Khwarizmi, whose book On the Calculation with Hindu Numerals written about 825, and the Arab mathematician Al-Kindi, who wrote four volumes, On the Use of the Indian Numerals (كتاب في استعمال العداد الهندي [kitab fi isti'mal al-'adad al-hindi]) about 830, are principally responsible for the diffusion of the Indian system of numeration in the Middle-East and the West [15].

The use of zero in positional systems dates to about this time, representing the final step to the system of numerals we are familiar with today.

The first dated and undisputed inscription showing the use of zero at is at Gwalior, dating to 876 AD. There were, however, Indian precursors from about 500 AD, positional notations without a zero, or with the word kha indicating the absence of a digit. It is, therefore, uncertain whether the crucial inclusion of zero as the tenth symbol of the system should be attributed to the Indians, or if it is due to Al-Khwarizmi or Al-Kindi of the House of Wisdom.

In the 10th century, Arab mathematicians extended the decimal numeral system to include fractions, as recorded in a treatise by Syrian mathematician Abu'l-Hasan al-Uqlidisi in 952-953.

In the Arab World—until modern times—the Hindu-Arabic numeral system was used only by mathematicians. Muslim scientists used the Babylonian numeral system, and merchants used the Abjad numerals, a system similar to the Greek numeral system and the Hebrew numeral system. Therefore, it was not until Fibonacci that the Hindu-Arabic numeral system was used by a large population.

Adoption in Europe

Leonardo Fibonacci brought this system to Europe, translating the Arabic text into Latin, calling it Liber Abaci. The numeral system came to be called "Arabic" by the Europeans. It was used in European mathematics from the 12th century, and entered common use from the 15th century. Robert Chester translated the Latin into English.

The words algorism and algorithm stem from Algoritmi, the Latinization of the name Al-Khwarizmi (Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī). His name is also the origin of the Spanish word guarismo, and of the Portuguese word algarismo [16], both meaning digit.

Adoption in East Asia

In China, Gautama Siddha introduced Indian numerals with zero in 718, but Chinese mathematicians didn't find them useful, as they had already had the decimal positional counting rods[6][7].

Even though, in Chinese numerals a circle (〇) is used to write zero in Suzhou numerals. Many historians think it was imported from Indian numerals by Gautama Siddha in 718, but some think it was created from the Chinese text space filler "□"[8].

Chinese and Japanese finally adopted the Western Arabic numerals in the 19th century, abandoning counting rods.

Notes

- ↑ Language may shape human thought, NewScientist.com news service, Celeste Biever, 19:00 19 August 2004.

- ↑ FAQ - Tamil Language and Script - Q: What can you tell me about Tamil Digit Zero?

- ↑ Unicode Technical Note #21: Tamil Numbers

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Flegg, pages 67-70.

- ↑ Ifrah, G. The Universal History of Numbers: From prehistory to the invention of the computer. John Wiley and Sons Inc., 2000. Translated from the French by David Bellos, E.F. Harding, Sophie Wood and Ian Monk

- ↑ Qian, Baocong (1964), Zhongguo Shuxue Shi (The history of Chinese mathematics), Beijing: Kexue Chubanshe

- ↑ Wáng, Qīngxiáng (1999), Sangi o koeta otoko (The man who exceeded counting rods), Tokyo: Tōyō Shoten, ISBN 4-88595-226-3

- ↑ Qian, Baocong (1964), Zhongguo Shuxue Shi (The history of Chinese mathematics), Beijing: Kexue Chubanshe

sick willy

References

- Flegg, Graham (2002). Numbers: Their History and Meaning. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0486421651.