Herpes zoster

| Herpes zoster Classification and external resources |

|

|

|

|---|---|

| Herpes zoster blisters on the neck and shoulder | |

| ICD-10 | B02. |

| ICD-9 | 053 |

| DiseasesDB | 29119 |

| MedlinePlus | 000858 |

| eMedicine | med/1007 derm/180 emerg/823 oph/257 ped/996 |

Herpes zoster (or simply zoster), commonly known as shingles, is a viral disease characterized by a painful skin rash with blisters in a limited area on one side of the body, often in a stripe. The initial infection with varicella zoster virus (VZV) causes the acute (short-lived) illness chickenpox, and generally occurs in children and young people. Once an episode of chickenpox has resolved, the virus is not eliminated from the body but can go on to cause shingles—an illness with very different symptoms—often many years after the initial infection.

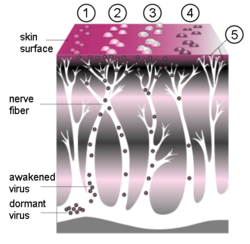

Varicella zoster virus can become latent in the nerve cell bodies and less frequently in non-neuronal satellite cells of dorsal root, cranial nerve or autonomic ganglion,[1] without causing any symptoms.[2] In an immunocompromised individual, perhaps years or decades after a chickenpox infection, the virus may break out of nerve cell bodies and travel down nerve axons to cause viral infection of the skin in the region of the nerve. The virus may spread from one or more ganglia along nerves of an affected segment and infect the corresponding dermatome (an area of skin supplied by one spinal nerve) causing a painful rash.[3][4] Although the rash usually heals within two to four weeks, some sufferers experience residual nerve pain for months or years, a condition called postherpetic neuralgia. Exactly how the virus remains latent in the body, and subsequently re-activates is not understood.[1]

Throughout the world the incidence rate of herpes zoster every year ranges from 1.2 to 3.4 cases per 1,000 healthy individuals, increasing to 3.9–11.8 per year per 1,000 individuals among those older than 65 years.[5][6][7] Antiviral drug treatment can reduce the severity and duration of herpes zoster, if a seven to ten day course of these drugs is started within 72 hours of the appearance of the characteristic rash.[5][8]

Contents |

Signs and symptoms

The earliest symptoms of herpes zoster, which include headache, fever, and malaise, are nonspecific, and may result in an incorrect diagnosis.[9][5] These symptoms are commonly followed by sensations of burning pain, itching, hyperesthesia (oversensitivity), or paresthesia ("pins and needles": tingling, pricking, or numbness).[10] The pain may be extreme in the affected dermatome, with sensations that are often described as stinging, tingling, aching, numbing or throbbing, and can be interspersed with quick stabs of agonizing pain.[11] In most cases, after 1–2 days (but sometimes as long as 3 weeks) the initial phase is followed by the appearance of the characteristic skin rash. The pain and rash most commonly occurs on the torso, but can appear on the face, eyes or other parts of the body. At first, the rash appears similar to the first appearance of hives; however, unlike hives, herpes zoster causes skin changes limited to a dermatome, normally resulting in a stripe or belt-like pattern that is limited to one side of the body and does not cross the midline.[10] Zoster sine herpete describes a patient who has all of the symptoms of herpes zoster except this characteristic rash.[12]

Later, the rash becomes vesicular, forming small blisters filled with a serous exudate, as the fever and general malaise continue. The painful vesicles eventually become cloudy or darkened as they fill with blood, crust over within seven to ten days, and usually the crusts fall off and the skin heals: but sometimes after severe blistering, scarring and discolored skin remain.[10]

| Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 5 | Day 6 |

|---|---|---|---|

Herpes zoster may have additional symptoms, depending on the dermatome involved. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus involves the orbit of the eye and occurs in approximately 10–25% of cases. It is caused by the virus reactivating in the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve. In a few patients, symptoms may include conjunctivitis, keratitis, uveitis, and optic nerve palsies that can sometimes cause chronic ocular inflammation, loss of vision, and debilitating pain.[13] Herpes zoster oticus, also known as Ramsay Hunt syndrome type II, involves the ear. It is thought to result from the virus spreading from the facial nerve to the vestibulocochlear nerve. Symptoms include hearing loss and vertigo (rotational dizziness).[1]

Diagnosis

If the rash has appeared, identifying this disease (making a differential diagnosis) only requires a visual examination, since very few diseases produce a rash in a dermatomal pattern (see map). However, herpes simplex virus (HSV) can occasionally produce a rash in such a pattern. The Tsanck smear is helpful for diagnosing acute infection with a herpes virus, but does not distinguish between HSV and VZV.[14]

When the rash is absent (early or late in the disease, or in the case of zoster sine herpete), herpes zoster can be difficult to diagnose.[15] Apart from the rash, most symptoms can occur also in other conditions.

Laboratory tests are available to diagnose herpes zoster. The most popular test detects VZV-specific IgM antibody in blood; this only appears during chickenpox or herpes zoster and not while the virus is dormant.[16] In larger laboratories, lymph collected from a blister is tested by the polymerase chain reaction for VZV DNA, or examined with an electron microscope for virus particles.[17]

In a recent study, samples of lesions on the skin, eyes, and lung from 182 patients with presumed herpes simplex or herpes zoster were tested with real-time PCR or with viral culture.[18] In this comparison, viral culture detected VZV with only a 14.3% sensitivity, although the test was highly specific (specificity=100%). By comparison, real-time PCR resulted in 100% sensitivity and specificity. Overall testing for herpes simplex and herpes zoster using PCR showed a 60.4% improvement over viral culture.

Pathophysiology

The causative agent for herpes zoster is varicella zoster virus (VZV), a double-stranded DNA virus related to the Herpes simplex virus group. Most people are infected with this virus as children, and suffer from an episode of chickenpox. The immune system eventually eliminates the virus from most locations, but it remains dormant (or latent) in the ganglia adjacent to the spinal cord (called the dorsal root ganglion) or the ganglion semilunare (ganglion Gasseri) in the base of the skull.[19] However, repeated attacks of herpes zoster are rare,[10] and it is extremely rare for patients to suffer more than three recurrences.[19]

Herpes zoster occurs only in people who have had chickenpox, and although it can occur at any age, the majority of sufferers are more than 50 years old.[20] The disease results from the virus reactivating in a single sensory ganglion.[4] In contrast to Herpes simplex virus, the latency of VZV is poorly understood. The virus has not been recovered from human nerve cells by cell culture and the location and structure of the viral DNA is not known. Virus-specific proteins continue to be made by the infected cells during the latent period, so true latency, as opposed to a chronic low-level infection, has not been proven.[2][21] Although VZV has been detected in autopsies of nervous tissue,[22] there are no methods to find dormant virus in the ganglia in living people.

Unless the immune system is compromised, it suppresses reactivation of the virus and prevents herpes zoster. Why this suppression sometimes fails is poorly understood,[6] but herpes zoster is more likely to occur in people whose immune system is impaired due to aging, immunosuppressive therapy, psychological stress, or other factors.[23] Upon reactivation, the virus replicates in the nerve cells, and virions are shed from the cells and carried down the axons to the area of skin served by that ganglion. In the skin, the virus causes local inflammation and blisters. The short and long-term pain caused by herpes zoster comes from the widespread growth of the virus in the infected nerves, which causes inflammation.[24]

The symptoms of herpes zoster cannot be transmitted to another person.[25] However, during the blister phase, direct contact with the rash can spread VZV to a person who has no immunity to the virus. This newly-infected individual may then develop chickenpox, but will not immediately develop shingles. Until the rash has developed crusts, a person is extremely contagious. A person is also not infectious before blisters appear, or during postherpetic neuralgia (pain after the rash is gone). The person is no longer contagious after the virus has disappeared.[10]

Prognosis

The rash and pain usually subside within three to five weeks, but about one in five patients develops a painful condition called postherpetic neuralgia, which is often difficult to manage. In some patients, herpes zoster can reactivate presenting as zoster sine herpete: pain radiating along the path of a single spinal nerve (a dermatomal distribution), but without an accompanying rash. This condition may involve complications that affect several levels of the nervous system and cause multiple cranial neuropathies, polyneuritis, myelitis, or aseptic meningitis. Other serious effects that may occur in some cases include partial facial paralysis (usually temporary), ear damage, or encephalitis.[1] During pregnancy, first infections with VZV, causing chickenpox, may lead to infection of the fetus and complications in the newborn, but chronic infection or reactivation in shingles are not associated with fetal infection.[26][27]

There is a slightly increased risk of developing cancer after a herpes zoster infection. However, the mechanism is unclear and mortality from cancer did not appear to increase as a direct result of the presence of the virus.[28] Instead, the increased risk may result from the immune suppression that allows the reactivation of the virus.[29]

Treatment

The aims of treatment are to limit the severity and duration of pain, shorten the duration of a shingles episode, and reduce complications. Symptomatic treatment is often needed for the complication of postherpetic neuralgia.[30]

Antiviral drugs inhibit VZV replication and reduce the severity and duration of herpes zoster with minimal side effects, but do not reliably prevent postherpetic neuralgia. Of these drugs, aciclovir has been the standard treatment, but the new drugs valaciclovir and famciclovir demonstrate similar or superior efficacy and good safety and tolerability.[30] The drugs are used both as prophylaxis (for example in AIDS patients) and as therapy during the acute phase. Antiviral treatment is recommended for all immunocompetent individuals with herpes zoster over 50 years old, preferably given within 72 hours of the appearance of the rash.[31] Complications in immunocompromised individuals with herpes zoster may be reduced with intravenous aciclovir. In people who are at a high risk for repeated attacks of shingles, five daily oral doses of aciclovir are usually effective.[1] Administering gabapentin along with antivirals may offer relief of postherpetic neuralgia.[30]

Patients with mild to moderate pain can be treated with over-the-counter analgesics. Topical lotions containing calamine can be used on the rash or blisters and may be soothing. Occasionally, severe pain may require an opioid medication, such as morphine. Once the lesions have crusted over, capsaicin cream (Zostrix) can be used. Topical lidocaine and nerve blocks may also reduce pain.[32]

Orally administered corticosteroids are frequently used in treatment of the infection, despite clinical trials of this treatment being unconvincing. Nevertheless, one trial studying immunocompetent patients older than 50 years of age with localized herpes zoster, suggested that administration of prednisone with aciclovir improved healing time and quality of life.[33] Upon one-month evaluation, aciclovir with prednisone increased the likelihood of crusting and healing of lesions by about two-fold, when compared to placebo. This trial also evaluated the effects of this drug combination on quality of life at one month, showing that patients had less pain, and were more likely to stop the use of analgesic agents, return to usual activities and have uninterrupted sleep. However, when comparing cessation of herpes zoster-associated pain or post herpetic neuralgia, there was no difference between aciclovir plus prednisone, or simply aciclovir alone. Because of the risks of corticosteroid treatment, it is recommended that this combination of drugs only be used in people more than 50 years of age, due to their greater risk of postherpetic neuralgia.[33]

Treatment for herpes zoster ophthalmicus is similar to standard treatment for herpes zoster at other sites. A recent trial comparing aciclovir with its prodrug, valaciclovir, demonstrated similar efficacies in treating this form of the disease.[34] The significant advantage of valciclovir over aciclovir is its dosing of only 3 times/day (compared with acyclovir's 5 times/day dosing), which could make it more convenient for patients and improve adherence with therapy.[35]

Prevention

A live vaccine for VZV exists, marketed as Zostavax. In a 2005 study of 38,000 older adults it prevented half the cases of herpes zoster and reduced the number of cases of postherpetic neuralgia by two-thirds.[36] A 2007 study found that the zoster vaccine is likely to be cost-effective in the U.S., projecting an annual savings of $82 to $103 million in healthcare costs with cost-effectiveness ratios ranging from $16,229 to $27,609 per quality-adjusted life year gained.[37] In October 2007 the vaccine was officially recommended in the U.S. for healthy adults aged 60 and over.[38] Adults also receive an immune boost from contact with children infected with varicella, a boosting method that prevents about a quarter of herpes zoster cases among unvaccinated adults, but which is becoming less common in the U.S. now that children are routinely vaccinated against varicella.[39][8]

In the United Kingdom and other parts of Europe, population-based immunization is not practiced. The rationale is that until the entire population could be immunized, adults who have previously contracted VZV would derive benefit from occasional exposure to VZV (from children), which serves as a booster to their immunity to the virus and may reduce the risk of shingles later on in life.[40] The UK Health Protection Agency states that while the vaccine is licensed in the UK there are no plans to introduce it into the routine childhood immunization scheme, although it may be offered to healthcare workers who have no immunity to VZV.[41]

A 2006 study of 243 cases and 483 matched controls found that fresh fruit is associated with a reduced risk of developing shingles: people who consumed less than one serving of fruit a day had three times the risk as those who consumed over three servings, after adjusting for other factors such as total energy intake. For those aged 60 or more, vitamins and vegetable intake had a similar association.[42]

Epidemiology

Varicella zoster virus has a high level of infectivity and is prevalent worldwide,[43] and has a very stable prevalence from generation to generation.[44] VZV is a benign disease in a healthy child in developed countries. However, varicella can be lethal to individuals who are infected later in life or who have low immunity. The number of people in this high-risk group has increased, due to the HIV epidemic and the increase in immunosuppressive therapies. Infections of varicella in institutions such as hospitals are also a significant problem, especially in hospitals that care for these high-risk populations.[45]

In general, herpes zoster has no seasonal incidence and does not occur in epidemics.[23] In temperate zones chickenpox is a disease of children, with most cases occurring during the winter and spring, most likely due to school contact; there is no evidence for regular epidemics. In the tropics chickenpox typically occurs among older people.[46] Incidence is highest in people who are over age 55, as well as in immunocompromised patients regardless of age group, and in individuals undergoing psychological stress. Non-whites may be at lower risk; it is unclear whether the risk is increased in females. Other potential risk factors include mechanical trauma, genetic susceptibility, and exposure to immunotoxins.[23]

The incidence rate of herpes zoster ranges from 1.2 to 3.4 per 1,000 person-years among healthy individuals, increasing to 3.9–11.8 per 1,000 person‐years among those older than 65 years.[5] Similar incidence rates have been observed worldwide.[7][5] Herpes zoster develops in an estimated 500,000 Americans each year.[47] Multiple studies and surveillance data demonstrate no consistent trends in incidence in the U.S. since the chickenpox vaccination program began in 1995.[48] It is likely that incidence rate will change in the future, due to the aging of the population, changes in therapy for malignant and autoimmune diseases, and changes in chickenpox vaccination rates; a wide adoption of zoster vaccination could dramatically reduce the incidence rate.[5]

In one study, it was estimated that 26% of patients who contract herpes zoster eventually present with complications. Postherpetic neuralgia arises in approximately 20% of patients.[49] A study of 1994 California data found hospitalization rates of 2.1 per 100,000 person-years, rising to 9.3 per 100,000 person-years for ages 60 and up.[50] An earlier Connecticut study found a higher hospitalization rate; the difference may be due to the prevalence of HIV in the earlier study, or to the introduction of antivirals in California before 1994.[51]

A 2008 study revealed that people with close relatives who have had shingles are themselves twice as likely to develop it themselves. The study speculates that there are genetic factors in who is more susceptible to VZV.[52]

History

Herpes zoster has a long recorded history, although historical accounts fail to distinguish the blistering caused by VZV and those caused by smallpox,[20] ergotism, and erysipelas. It was only in the late eighteenth century that William Heberden established a way to differentiate between herpes zoster and smallpox,[45] and only in the late nineteenth century that herpes zoster was differentiated from erysipelas. The first indications that chickenpox and herpes zoster were caused by the same virus were noticed at the beginning of the 20th century. Physicians began to report that cases of herpes zoster were often followed by chickenpox in the younger people who lived with the shingles patients. The idea of an association between the two diseases gained strength when it was shown that lymph from a sufferer of herpes zoster could induce chickenpox in young volunteers. This was finally proved by the first isolation of the virus in cell cultures, by the Nobel laureate Thomas H. Weller in 1953.[53]

Until the 1940s, the disease was considered benign, and serious complications were thought to be very rare.[54] However, by 1942, it was recognized that herpes zoster was a more serious disease in adults than in children and that it increased in frequency with advancing age. Further studies during the 1950s on immunosuppressed individuals showed that the disease was not as benign as once thought, and the search for various therapeutic and preventive measures began.[45] By the mid-1960s, several studies identified the gradual reduction in cellular immunity in old age, observing that in a cohort of 1,000 people who lived to the age of 85, approximately 500 would have one attack of herpes zoster and 10 would have two attacks.[55]

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Johnson, RW & Dworkin, RH (2003). "Clinical review: Treatment of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia". BMJ 326 (7392): 748. doi:. PMID 12676845. http://www.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/326/7392/748.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Kennedy PG (2002). "Varicella-zoster virus latency in human ganglia". Rev. Med. Virol. 12 (5): 327–34. doi:. PMID 12211045.

- ↑ Peterslund NA (1991). "Herpesvirus infection: an overview of the clinical manifestations". Scand J Infect Dis Suppl 80: 15–20. PMID 1666443.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Gilden DH, Cohrs RJ, Mahalingam R (2003). "Clinical and molecular pathogenesis of varicella virus infection". Viral Immunol 16 (3): 243–58. doi:. PMID 14583142.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Dworkin RH, Johnson RW, Breuer J et al. (2007). "Recommendations for the management of herpes zoster". Clin. Infect. Dis 44 Suppl 1: S1–26. doi:. PMID 17143845. http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/510206.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Donahue JG, Choo PW, Manson JE, Platt R (1995). "The incidence of herpes zoster". Arch. Intern. Med 155 (15): 1605–9. doi:. PMID 7618983.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Araújo LQ, Macintyre CR, Vujacich C (2007). "Epidemiology and burden of herpes zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia in Australia, Asia and South America" (PDF). Herpes 14 (Suppl 2): 40A–4A. PMID 17939895. http://www.ihmf.org/journal/download/5%20-%20Herpes%2014.2%20suppl%20Araujo.pdf.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Cunningham AL, Breuer J, Dwyer DE, Gronow DW, Helme RD, Litt JC, Levin MJ, Macintyre CR (2008). "The prevention and management of herpes zoster". Med. J. Aust. 188 (3): 171–6. PMID 18241179.

- ↑ Zamula E (2001). "Shingles: An Unwelcome Encore". FDA Consum 35 (3): 21–5. PMID 11458545. http://www.fda.gov/fdac/features/2001/301_pox.html. Retrieved on 2007-12-15. Revised June 2005.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Stankus SJ, Dlugopolski M, Packer D (2000). "Management of herpes zoster (shingles) and postherpetic neuralgia". Am Fam Physician 61 (8): 2437–44, 2447–8. PMID 10794584. http://www.aafp.org/afp/20000415/2437.html.

- ↑ Katz J, Cooper EM, Walther RR, Sweeney EW, Dworkin RH (2004). "Acute pain in herpes zoster and its impact on health-related quality of life". Clin. Infect. Dis 39 (3): 342–8. doi:. PMID 15307000. http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/421942.

- ↑ Furuta Y, Ohtani F, Mesuda Y, Fukuda S, Inuyama Y (2000). "Early diagnosis of zoster sine herpete and antiviral therapy for the treatment of facial palsy". Neurology 55 (5): 708–10. PMID 10980741.

- ↑ Shaikh S, Ta CN (2002). "Evaluation and management of herpes zoster ophthalmicus". Am Fam Physician 66 (9): 1723–1730. PMID 12449270. http://www.aafp.org/afp/20021101/1723.html.

- ↑ Oranje AP, Folkers E (1988). "The Tzanck smear: old, but still of inestimable value". Pediatr Dermatol 5 (2): 127–9. doi:. PMID 2842739.

- ↑ Chan J, Bergstrom RT, Lanza DC, Oas JG (2004). "Lateral sinus thrombosis associated with zoster sine herpete". Am J Otolaryngol 25 (5): 357–60. doi:. PMID 15334402.

- ↑ Arvin AM (1996). "Varicella-zoster virus" (PDF). Clin. Microbiol. Rev 9 (3): 361–81. PMID 8809466. http://cmr.asm.org/cgi/reprint/9/3/361.pdf.

- ↑ Beards G, Graham C, Pillay D (1998). "Investigation of vesicular rashes for HSV and VZV by PCR". J. Med. Virol 54 (3): 155–7. doi:. PMID 9515761.

- ↑ Stránská R, Schuurman R, de Vos M, van Loon AM. (2003). "Routine use of a highly automated and internally controlled real-time PCR assay for the diagnosis of herpes simplex and varicella-zoster virus infections". J Clin Virol. 30 (1): 39–44. doi:. PMID 15072752.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Steiner I, Kennedy PG, Pachner AR (2007). "The neurotropic herpes viruses: herpes simplex and varicella-zoster". Lancet Neurol 6 (11): 1015–28. doi:. PMID 17945155.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Weinberg JM (2007). "Herpes zoster: epidemiology, natural history, and common complications". J Am Acad Dermatol 57 (6 Suppl): S130–5. doi:. PMID 18021864.

- ↑ Kennedy PG (2002). "Key issues in varicella-zoster virus latency". J. Neurovirol 8 Suppl 2: 80–4. doi:. PMID 12491156.

- ↑ Mitchell BM, Bloom DC, Cohrs RJ, Gilden DH, Kennedy PG (2003). "Herpes simplex virus-1 and varicella-zoster virus latency in ganglia" (PDF). J. Neurovirol 9 (2): 194–204. doi:10.1080/13550280390194000 (inactive 2008-06-25). PMID 12707850. http://www.jneurovirol.com/o_pdf/9(2)/194-204.pdf.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Thomas SL, Hall AJ (2004). "What does epidemiology tell us about risk factors for herpes zoster?". Lancet Infect Dis 4 (1): 26–33. doi:. PMID 14720565.

- ↑ Schmader K (2007). "Herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults". Clin. Geriatr. Med. 23 (3): 615–32, vii–viii. doi:. PMID 17631237. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0749-0690(07)00021-3.

- ↑ Schmader K (1999). "Herpes zoster in the elderly: issues related to geriatrics". Clin. Infect. Dis 28 (4): 736–9. doi:. PMID 10825029.

- ↑ Paryani SG, Arvin AM (1986). "Intrauterine infection with varicella-zoster virus after maternal varicella". N. Engl. J. Med. 314 (24): 1542–6. PMID 3012334.

- ↑ Enders G, Miller E, Cradock-Watson J, Bolley I, Ridehalgh M (1994). "Consequences of varicella and herpes zoster in pregnancy: prospective study of 1739 cases". Lancet 343 (8912): 1548–51. doi:. PMID 7802767.

- ↑ Sørensen HT, Olsen JH, Jepsen P, Johnsen SP, Schønheyder HC, Mellemkjaer L (2004). "The risk and prognosis of cancer after hospitalisation for herpes zoster: a population-based follow-up study". Br. J. Cancer 91 (7): 1275–9. doi:. PMID 15328522.

- ↑ Ragozzino MW, Melton LJ, Kurland LT, Chu CP, Perry HO (1982). "Risk of cancer after herpes zoster: a population-based study". N. Engl. J. Med. 307 (7): 393–7. PMID 6979711.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Tyring SK (2007). "Management of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia". J Am Acad Dermatol 57 (6 Suppl): S136–42. doi:. PMID 18021865.

- ↑ Breuer J, Whitley R (2007). "Varicella zoster virus: natural history and current therapies of varicella and herpes zoster" (PDF). Herpes 14 (Supplement 2): 25–9.. PMID 17939892. http://www.ihmf.org/journal/download/2%20-%20Herpes%2014.2%20suppl%20Breuer.pdf.

- ↑ Baron R (2004). "Post-herpetic neuralgia case study: optimizing pain control". Eur. J. Neurol 11 Suppl 1: 3–11. doi:. PMID 15061819.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Whitley RJ, Weiss H, Gnann JW, Tyring S, Mertz GJ, Pappas PG, Schleupner CJ, Hayden F, Wolf J, Soong SJ (1996). "Acyclovir with and without prednisone for the treatment of herpes zoster. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Collaborative Antiviral Study Group". Ann. Intern. Med. 125 (5): 376–83. PMID 8702088.

- ↑ Colin J, Prisant O, Cochener B, Lescale O, Rolland B, Hoang-Xuan T (2000). "Comparison of the Efficacy and Safety of Valaciclovir and Acyclovir for the Treatment of Herpes zoster Ophthalmicus". Ophthalmology 107 Number 8: 1507–11. doi:. PMID 10919899.

- ↑ Osterberg L, Blaschke T (2005). "Adherence to medication". N Engl J Med 353 Number 5: 487–97. doi:. PMID 16079372.

- ↑ Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Johnson GR, Schmader KE, Straus SE, Gelb LD et al. (2005). "A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults". N Engl J Med 253 (22): 2271–84. doi:. PMID 15930418.

- ↑ Pellissier JM, Brisson M, Levin MJ (2007). "Evaluation of the cost-effectiveness in the United States of a vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults". Vaccine 25 (49): 8326–37. doi:. PMID 17980938.

- ↑ Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (2007). "Recommended adult immunization schedule: United States, October 2007–September 2008". Ann Intern Med 147 (10): 725–9. PMID 17947396. http://www.annals.org/cgi/content/full/147/10/725.

- ↑ Brisson M, Gay N, Edmunds W, Andrews N (2002). "Exposure to varicella boosts immunity to herpes-zoster: implications for mass vaccination against chickenpox". Vaccine 20 (19–20): 2500–7. doi:. PMID 12057605.

- ↑ NHS Direct (2008-02-07). "Why isn’t the chickenpox vaccine available in the UK?". Retrieved on 2008-03-22.

- ↑ Health Protection Agency (2006-05-11). "Chickenpox / Varicella - General Information". Retrieved on 2008-03-22.

- ↑ Thomas SL, Wheeler JG, Hall AJ (2006). "Micronutrient intake and the risk of herpes zoster: a case-control study". Int J Epidemiol 35 (2): 307–14. doi:. PMID 16330478. http://ije.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/35/2/307.

- ↑ Apisarnthanarak A, Kitphati R, Tawatsupha P, Thongphubeth K, Apisarnthanarak P, Mundy LM (2007). "Outbreak of varicella-zoster virus infection among Thai healthcare workers". Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 28 (4): 430–4. doi:. PMID 17385149.

- ↑ Abendroth A, Arvin AM (2001). "Immune evasion as a pathogenic mechanism of varicella zoster virus". Semin. Immunol. 13 (1): 27–39. doi:. PMID 11289797.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Weller TH (1997). Varicella-herpes zoster virus. In: Viral Infections of Humans: Epidemiology and Control. Evans AS, Kaslow RA, eds.. Plenum Press. pp. 865-892. ISBN 978-0306448553.

- ↑ Wharton M (1996). "The epidemiology of varicella-zoster virus infections". Infect Dis Clin North Am 10 (3): 571–81. doi:. PMID 8856352.

- ↑ Insinga RP (2005). "The incidence of herpes zoster in a United States administrative database". J Gen Intern Med 20 (6): 748–753. doi:. PMID 16050886. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=16050886.

- ↑ Marin M, Güris D, Chaves SS, Schmid S, Seward JF (2007). "Prevention of varicella: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)". MMWR Recomm Rep 56 (RR-4): 1–40. PMID 17585291. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5604a1.htm.

- ↑ Volpi A (2007). "Severe complications of herpes zoster" (PDF). Herpes 14 (Suppl 2): 35A–9A. PMID 17939894. http://www.ihmf.org/journal/download/4%20-%20Herpes%2014.2%20suppl%20Volpi.pdf.

- ↑ Coplan P, Black S, Rojas C (2001). "Incidence and hospitalization rates of varicella and herpes zoster before varicella vaccine introduction: a baseline assessment of the shifting epidemiology of varicella disease". Pediatr Infect Dis J 20 (7): 641–5. PMID 11465834.

- ↑ Weaver BA (2007). "The burden of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in the United States". J Am Osteopath Assoc 107 (3 Suppl): S2–7. PMID 17488884. http://www.jaoa.org/cgi/content/full/107/suppl_1/S2.

- ↑ Hicks LD, Cook-Norris RH, Mendoza N, Madkan V, Arora A, Tyring SK (May 2008). "Family history as a risk factor for herpes zoster: a case-control study". Arch Dermatol 144 (5): 603–8. doi:. PMID 18490586.

- ↑ Weller TH (1953). "Serial propagation in vitro of agents producing inclusion bodies derived from varicella and herpes zoster". Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 83 (2): 340–6. PMID 13064265.

- ↑ Holt LE & McIntosh R (1936). Holt's Diseases of Infancy and Childhood. D Appleton Century Company. pp. 931–3.

- ↑ Hope-Simpson RE (1965). "The nature of herpes zoster; a long-term study and a new hypothesis". Proc R Soc Med 58: 9–20. PMID 14267505. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1898279.

External links

- NINDS Shingles Information Page, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

- Herpes zoster at the Open Directory Project

- Links to pictures of Shingles (Hardin MD) University of Iowa

- After Shingles—Information about Shingles and Post-Herpetic Neuralgia, from the Visiting Nurses Associations of America

- Facts About The Cornea and Corneal Disease: Herpes Zoster (Shingles), National Eye Institute

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||