Hermit

A hermit (from the Greek ἔρημος erēmos, signifying "desert", "uninhabited", hence "desert-dweller"; adjective: "eremitic") is a person who lives to some greater or lesser degree in seclusion and/or isolation from society.

In Christianity the term was originally applied to a Christian who lives the eremitic life out of a religious conviction, namely the Desert Theology of the Old Testament (i.e. the forty years wandering in the desert[1] that was meant to bring about a change of heart).

In the Christian tradition the eremitic life is an early form of monastic living that preceded the monastic life in the cenobium. The Rule of St Benedict (ch. 1) lists hermits among four kinds of monks. In addition to hermits that are members of religious orders, modern Roman Catholic Church law (canon 603) recognises also consecrated hermits under the direction of their diocesan bishop as members of the Consecrated Life.

Often – both in religious and secular literature – the term "hermit" is used loosely for anyone living a solitary life-style – including the misanthrope – and in religious contexts is sometimes assumed to be interchangeable with anchorite / anchoress (from the Greek ἀναχωρέω anachōreō, signifying "to withdraw", "to depart into the country outside the circumvallated city"), recluse and solitary. However, it is important to retain a clear distinction between the vocation of hermits and that of anchorites.

Contents |

The Christian eremitic life

Because the life of the Christian hermit, both in ancient and in modern times, is rooted in the Desert Theology of the Old Testament, it is a life entirely given to the praise of God and the love and – through the hermit's penance and prayers – also the service of all humanity. The latter is crucial to the correct understanding of the eremitic vocation, since the Judeo-Christian tradition holds that God created man (i.e. the individual human being) relational,[2] which means that solitude can never be the purpose of any Christian vocation but only a conducive environment for striving after a particular spiritual purpose that forms part of our common human vocation.

History

The eremitic tradition

In the common Christian tradition the first known Christian hermit in Egypt was Paul of Thebes (fl. 3rd century), hence also called "St Paul the first hermit". His disciple Antony of Egypt (fl. 4th century), often referred to as "Antony the Great", is perhaps the most renowned of all the very early Christian hermits owing to the biography by his friend Athanasius of Alexandria. An antecedent for Egyptian eremitism may have been the Syrian solitary or "son of the covenant" (Aramaic bar qəyāmā) who undertook special disciplines as a Christian.[3] In the Middle Ages some Carmelite hermits claimed to trace their origin to Jewish hermits organized by Elijah.

Christian hermits in the past have often lived in isolated cells or hermitages, whether a natural cave or a constructed dwelling, situated in the desert or the forest. They tended to be sought out for spiritual advice and counsel; and some eventually acquired so many disciples that they had no physical solitude at all.

The early Christian Desert Fathers wove baskets to exchange for bread. In medieval times hermits were also found within or near cities where they might earn a living as a gate keeper or ferryman.

From the Middle Ages and down to modern times eremitical monasticism has also been practiced within the context of religious orders in the Christian West. For example in the Roman Catholic Church the Carthusians and Camaldolese arrange their monasteries as clusters of hermitages where the monks live most of their day and most of their lives in solitary prayer and work, gathering only relatively briefly for communal prayer and only occasionally for community meals and recreation. The Cistercian, Trappist and Carmelite orders, which are essentially communal in nature, allow members who feel a calling to the eremitic life, after years living in the cenobium or community of the monastery, to move to a cell suitable as a hermitage on monastery grounds. This applies to both their monks and their nuns.

Anchorites and anchoresses

- Main article: Anchorite

The term "anchorite" is often used as a synonym for hermit, not only in the earliest written sources but throughout the centuries down to our times. Yet the anchoritic life, while similar to the eremitic life, can also be distinct from it. In the Middle Ages it was a common vocation. Anchorites and anchoresses lived the religious life in the solitude of an "anchorhold" (or "anchorage"), usually a small hut or "cell" built against a church. The door of anchorages tended to be bricked up in a special ceremony conducted by the local bishop after the anchorite had moved in. Medieval churches survive that have a tiny window ("squint") built into the shared wall near the sanctuary to allow the anchorite to participate in the liturgy by listening to the service and to receive Holy communion. Another window led out into the street, enabling charitable neighbours to deliver food and other necessities. In our times the anchoritic life as a distinct form of vocation is almost unheard of.

Contemporary eremitic life

In the Roman Catholic Church

Today's Catholics feeling called to eremitic monasticism may live that vocation either

- as a hermit (a) belonging to a cenobitic religious order (for example Benedictines, Cistercians), or (b) in an eremitically-oriented religious order (for example Carthusian, Camaldolese), but in both cases under obedience to their religious superior (see below), or

- as a consecrated hermit under the canonical direction of their local bishop (canon 603, see below).

As a member of a religious order

In the Roman Catholic Church today the institutes of consecrated life have their own regulations concerning those of their members who feel called by God to move from the life in community to the eremitic life, and have the permission of their religious superior to do so. The Code of Canon Law (1983) contains no special provisions for them. They technically remain a member of their religious order and thus under obedience to their religious superior.

As mentioned above, the Carthusian and Camaldolese orders of monks and nuns preserve their original way of life as essentially eremitical within a cenobitical context: that is, the monasteries of these orders are in fact clusters of individual hermitages where monks and nuns spend their days alone with relatively short periods of prayer in common daily and weekly.

Also as mentioned above, other orders which are essentially cenobitical, most notably the Trappists, maintain a tradition that allows individual monks or nuns, when they have reached a certain level of maturity within the community, to pursue the life of the hermit on monastery grounds under the supervision of the abbot or abbess. Thomas Merton was among those Trappists who undertook this way of life.

Under the direction of the diocesan bishop (canon 603)

The earliest form of Christian eremitic or anchoritic living preceded that as a member of a religious order, since monastic communities and religious orders are later developments of the monastic life. Today an increasing number of Christian faithful feel again a vocation to live the eremitic life, whether in the remote country side or in a city in stricter separation from the world, without having passed through life in a monastic community first. Bearing in mind that the meaning of the eremitic vocation is the Desert Theology of the Old Testament (i.e. the 40 years wandering in the desert that was meant to bring about a change of heart), it may be said that the desert of the urban hermit is that of their heart, purged through kenosis to be the dwelling place of God alone.

So as to provide for men and women who feel a calling to the eremitic or anchoritic life without being or becoming a member of an institute of consecrated life, but desire its recognition by the Church as a form of consecrated life nonetheless, the Code of Canon Law 1983 legislates in the Section on Consecrated Life (canon 603) as follows:

§1 Besides institutes of consecrated life the Church recognizes the eremitic or anchoritic life by which the Christian faithful devote their life to the praise of God and salvation of the world through a stricter separation from the world, the silence of solitude and assiduous prayer and penance.

§2 A hermit is recognized in the law as one dedicated to God in a consecrated life if he or she publicly professes the three evangelical counsels" (i.e. chastity, religious poverty and obedience), "confirmed by a vow or other sacred bond, in the hands of the diocesan bishop and observes his or her own plan of life under his direction.

Canon 603 §2 therefore lays down certain requirements for those who feel a vocation to the kind of eremitic life that is recognized by the Church as one of the "other forms of consecrated life". They usually are referred to as "consecrated hermits".

The norms of canon 603 do not apply to the many other Christian faithful who live alone and devote themselves to fervent prayer for the love of God without however feeling called by God to seek recognition of their prayerful solitary life from the Church by entering the consecrated life.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church of 11 October 1992 (§§918-921) comments on the eremitic life as follows:

From the very beginning of the Church there were men and women who set out to follow Christ with greater liberty, and to imitate him more closely, by practicing the evangelical counsels. They led lives dedicated to God, each in his own way. Many of them, under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, became hermits or founded religious families. These the Church, by virtue of her authority, gladly accepted and approved.

Bishops will always strive to discern new gifts of consecrated life granted to the Church by the Holy Spirit; the approval of new forms of consecrated life is reserved to the Apostolic See. (Footnote: Cf. CIC, can. 605).

The Eremitic Life

Without always professing the three evangelical counsels publicly, hermits "devote their life to the praise of God and salvation of the world through a stricter separation from the world, the silence of solitude and assiduous prayer and penance". (Footnote: CIC, can. 603 §1)

They manifest to everyone the interior aspect of the mystery of the Church, that is, personal intimacy with Christ. Hidden from the eyes of men, the life of the hermit is a silent preaching of the Lord, to whom he has surrendered his life simply because he is everything to him. Here is a particular call to find in the desert, in the thick of spiritual battle, the glory of the Crucified One.

The norms of the Roman Catholic Church for the consecrated eremitic and anchoritic life (cf. canon 603) do not include corporal works of mercy. Nevertheless, every consecrated hermit – like every Christian – is bound by the law of charity and therefore ought to respond generously, as his or her own circumstances permit, when faced with a specific need for corporal works of mercy. However, since consecrated hermits – again, like every Christian – are also bound by the law of work, and therefore have to earn their living, they have to do so by any means locally available that is compatible with Christian teaching. Therefore (self-)employment in the care sector may be a work option for consecrated hermits so qualified, providing they can convince their bishop that this will not keep them from observing their obligations of the eremitic vocation in accordance with canon 603, under which they have made their vow.

Whilst canon 603 makes no provison for associations of hermits, these do exist (for example the "Hermits of Bethlehem" in Chester NJ and the "Hermits of Saint Bruno" in the U.S.A.; see also lavra, skete).

Eremitic-style Catholic living that is not a form of consecrated life

Not all the Catholic faithful that feel that it is their vocation to dedicate themselves to God in a prayerful solitary life perceive it as a vocation to some form of consecrated life. An example of this is life in a Poustinia, an Eastern Catholic expression of eremitic religious living that is finding adherents also in the West.

Eastern Christian Eremiticism

In the Orthodox Church and Eastern Rite Catholic Churches, however, hermits live a life not only of prayer but also of service to their community in the traditional Eastern Christian manner of the poustinik. The poustinik is a hermit available to all in need and at all times.

In the Eastern Christian churches one traditional variation of the Christian eremitic life is the semi-eremitic life in a lavra or skete, exemplified historically in Scetes, a place in the Egyptian desert, and continued in various sketes today, such as in the St Isaac of Syria Skete[4] and several regions on Mount Athos.

Some noted Christian hermits

Early and Medieval Church

- Anthony of Egypt, 4th cent., Egypt, a Desert Father, regarded as the founder of Monasticism

- St Benedict of Nursia, 6th cent., Italy, author of the so-called Rule of St Benedict, regarded as the founder of western monasticism

- St. Bruno of Cologne, 11th cent., France, the founder of the Carthusian order

- Gregory the Illuminator, brought the Christian faith to Armenia

- Macarius of Egypt, 4th cent., founder of the Monastery of Saint Macarius the Great, presumed author of "Spiritual Homilies"

- Mary of Egypt, 4/5th cent., Egypt and Transjordan, penitent

- Richard Rolle de Hampole, 13th cent., England, religious writer

- St. Romuald, 10/11th cent., Italy, founder of the Camaldolese order

- Simeon Stylites, 4/5th cent., Syria, "pillar hermit"/"pillar saint"

Modern times – Roman Catholic Church

- Hermit members of religious orders:

- Maria Boulding, Benedictine nun, spiritual writer

- Thomas Merton, 20th cent., Cistercian monk, spiritual writer

- Consecrated hermits (canon 603):

- Sr Scholastica Egan, writer on the eremitic vocation

- Colonies, sketes, lavras of Consecrated Hermits (canon 603):

- Hermits of Bethlehem, Chester, NJ (modern lavra)

- Christian faithful living an eremitic form of life without belonging to a religious order or being a Consecrated Hermit (canon 603):

- Sister Wendy Beckett, formerly of the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur, since 1970 Consecrated virgin, lives in "monastic solitude"; art historian

- Catherine de Hueck Doherty, poustinik, foundress of the Madonna House Apostolate

- Charles de Foucauld, 19/20th cent., formerly Trappist monk, inspired the founding of the Little Brothers of Jesus

- Jan Tyranowski, spiritual mentor to the young Karol Wojtyla, who would eventually become Pope John Paul II

Modern times – Orthodox Church

- Herman of Alaska, 18th cent.

- Seraphim of Sarov, 18/19th cent.

- Sergius of Radonezh, 14th cent.

Modern Times - Protestant Churches

- Order of Watchers, a contemporary French Protestant eremitic fraternity.

Hermits in other religions

From a religious point of view, the solitary life is a form of asceticism, wherein the hermit renounces worldly concerns and pleasures in order to come closer to the deity or deities they worship or revere. This practice appears also in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Sufism. Taoism also has a long history of ascetic and eremetical figures. In the ascetic eremitic life, the hermit seeks solitude for meditation, contemplation, and prayer without the distractions of contact with human society, sex, or the need to maintain socially acceptable standards of cleanliness or dress. The ascetic discipline can also include a simplified diet and/or manual labor as a means of support.

Some noted hermits in other religions

- Gautama Buddha, who, having abandoned his family for a solitary quest for spiritual enlightenment, became the founder of Buddhism.

- Laozi, in some traditions he spent his final days as a hermit.

- U Khandi, Religious figure in Burma.

- Yoshida Kenkō, Japanese author.

- Zhang Daoling, Founder of Tianshi Dao.

Other hermits

In philosophy and fiction

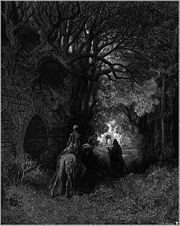

In medieval romances, the knight errant frequently encountered hermits on his quest; such a figure, generally a wise old man, would advise him. Knights searching for the Holy Grail, in particular, would learn the errors they had to repent of, and have the significance of their encounters explained to them.[5] Evil wizards would sometimes pose as hermits, to explain their presence in the wilds, and to lure heroes into a false sense of security. In Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene, both occurred: the knight on a quest met a good hermit, and the sorcerer Archimago took on such a pose.[6]

Hermits can appear in fairy tales in the character of the donor, as in Făt-Frumos with the Golden Hair.

Friedrich Nietzsche, in his influential work Thus Spoke Zarathustra, created the character of the hermit Zarathustra (named after the Zoroastrian prophet Zarathushtra), who emerges from seclusion to extol his philosophy to the rest of humanity.

In Star Wars, Ben Kenobi, was first introduced to the audience as an old hermit, often seen by most of the in-universe characters at their surroundings as a very dangerous, crazy wizard. Later in the story it was to be revealed that he went into exile for political reasons, although it also served him for spiritual training since he was a warrior monk in his youth, and that his first name was actually Obi-Wan.

In the Friday the 13th series, the character Jason Voorhees was believed to have died after he drowned as a child. However, this later changed when it was revealed that he survived and lived life as a hermit- only to enter a murderous rage when he witness the death of his mother seemingly years later (which was during the events of the original film).

In the popular Anime Dragon Ball a martial-arts master named Muten Roshi is often referred to as a Turtle Hermit, despite the fact that over the course of the series characters are often visiting or even living in his island home.

Non-spiritual motivations

In modern parlance the term "hermit" tends to be applied to anyone living a life apart from the rest of society, regardless of their motivation.

During the Romantic period of the 19th century some wealthy estate owners would pay imitation "hermits" to inhabit their properties, as living garden decorations.

This article incorporates text from the public domain 1913 Webster's Dictionary.

See also

- Monasticism

- Hermitage

- Skete (a group of hermits living singly in hermitages but with a common rule and church/chapel)

- Lavra (cluster of cells for hermits, with a common refectory and church)

- Desert Theology

- God: Sole Satisfier

- Solitude

- Silence

- "Into Great Silence" a documentary on eremitic life as expressed within the Carthusian motherhouse of 'La Grande Chartreuse'.

- Hermit brother Hugo's "Hermitage of Our Lady the Garden Enclosed"

- Stylites

- Poustinia

- Recluse

- Hikikomori

- New Monasticism

References

- ↑ Numbers 13:3, Numbers 13:26

- ↑ cf. e.g. Joseph Ratzinger (now Pope Benedict XVI), "In the Beginning", Edinburgh 1995, pp. 47, 72, ISBN 0 567 29296 7.

- ↑ Re: the Syrian "son of the covenant"

- ↑ St Isaac of Syria Skete

- ↑ Penelope Reed Doob, The Idea of the Labyrinth: from Classical Antiquity through the Middle Ages, p 179-81, ISBN 0-8014-8000-0

- ↑ C. S. Lewis, Spenser's Images of Life, p 87, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1967

External links

Hermits in the East as well as the West and related subjects

The Roman Catholic eremitic life

- Chapter 1 of The Rule of Saint Benedict re: the hermit as one of the kinds of monks

- Text of canon 603 of The Code of Canon Law (1983, English translation) re: Hermits as members of the Consecrated Life in the Catholic Church

- Catechism of the Catholic Church on Consectrated and Eremitic Life

- Chart showing the place of the Consecrated Hermit (canon 603) among the People of God

- Immaculate Heart of Mary's Hermitage Catholic, hermit, solitude, silence, contemplation

- Raven's Bread is a quarterly newsletter for hermits and those interested in the eremitical life

- The Hermits of Bethlehem, Chester, NJ. (a modern laura)

- anchorite?

- Hermits of the Carmelite Order

- Contemplative spirituality in the tradition of the medieval hermits who settled on Mount Carmel.

- Catholic Encyclopedia Entry on hermits

Buddhist Lersi hermits