Hebrew Bible

The term Hebrew Bible is a generic reference to those books of the Bible originally written in Biblical Hebrew (and Biblical Aramaic). The term closely corresponds to contents of the Jewish Tanakh and the Protestant Old Testament (see also Judeo-Christian) but does not include the deuterocanonical portions of the Roman Catholic or the Anagignoskomena portions of the Eastern Orthodox Old Testaments. The term does not imply naming, numbering or ordering of books, which varies, see also Biblical canon.

Contents |

Usage

| Books of the Hebrew Bible |

|---|

| for Jewish Bible see Tanakh English Names

|

Hebrew Bible is a term that refers to the common portions of the Jewish canon and the Christian canons. In its Latin form, Biblia Hebraica, it traditionally serves as a title for printed editions of the masoretic text.

Many scholars advocate use of the term Hebrew Bible when discussing these books in academic writing, as a neutral substitute to terms with religious connotations.[1] The Society of Biblical Literature's Handbook of Style, which is the standard for major academic journals like Harvard Theological Review and conservative Protestant journals like Bibliotheca Sacra and Westminster Theological Journal, suggests that authors "be aware of the connotations of alternative expressions such as ... Hebrew Bible [and] Old Testament" without prescribing the use of either.[2]

Additional difficulties include:

- In terms of theology, Christianity has struggled with the relationship between "old" and "new" testaments from its very beginnings.[3][4] Modern Christian formulations of this tension, sometimes building upon ancient and medieval ideas, include supersessionism, covenant theology, dispensationalism, and dual covenant theology. However, all of these formulations, except some forms of dual covenant theology, are objectionable to mainstream Judaism and to many Jewish scholars and writers, for whom there is only one everlasting covenant, and who therefore reject the very term Old Testament.

- In terms of canon, Christian usage of Old Testament does not refer to a universally agreed upon set of books, but rather varies depending on denomination.

- Though commonly used by Jews, the term Tanakh is derived from Hebrew names (Torah-Nevi'im-Ketuvim) unlikely to be appreciated by readers unfamiliar with that language and culture. It also refers to the particular arrangement of the biblical books as found in Judaism, and even to the exact features of the masoretic text. None of this is central to the Bible in the Christian textual tradition.

Hebrew in the term Hebrew Bible refers to the original language of the books, but it may also be taken as referring to the Jews of the second temple era and the Diaspora, who preserved the transmission of the text up to the age of printing . The Hebrew Bible includes some small portions in Aramaic (mostly in the books of Daniel and Ezra), which are nonetheless written and printed in the Hebrew alphabet and script, which is the same as Aramaic square-script. Some Qumran Hebrew biblical manuscripts are written using the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet of the classical era of Solomon's Temple. [5] The famous examples of the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet are the Siloam inscription (8th century BCE), the Lachish ostraca, and the Bar Kokhba coin (circa 132 CE).

Origin and History

Many contemporary secular biblical scholars date the origin of the Hebrew Bible to the Persian period (539 to 334 BCE).[6]

Meaning of old in Old Testament

- See also: Biblical law in Christianity and Development of the Old Testament canon

Another important issue relevant to use of Hebrew Bible rather than Old Testament is the documented misunderstanding of the sense of old in Old Testament. In Christianity old in Old Testament essentially refers to time. In French it is Ancien Testament, in Latin Vetus Testamentum (like Vetus Latina Old Latin), in Greek hē palaia diathēkē (Ἡ Παλαιὰ Διαθήκη, palaios gives several English prefixes like palaeography). There is additional, confessional implication, but the semantics of this is non-trivial, related to the meaning of Testament rather than the meaning of Old.

Christian commentary on the New Testament understanding of the relationship between the Testaments became controversial in the 2nd century and remains controversial today, see Old Testament for details.

The controversy arose when Marcion and his followers held the Hebrew scriptures to be inferior (the work of a demiurge) and superseded by the revelation of Christ. Along with Gnosticism, this view has the dubious distinction of being one of the first to be classed as heretical by the early Christian "peer review" process.[3] The Catholic Encyclopedia notes that Marcion "rejected the writings of the Old Testament" and claims that the Marcionites "were perhaps the most dangerous foe Christianity has ever known."[7]

Both Gnosticism (with its additional pseudepigraphal gospels) and Marcion (with his limited canon) stimulated early Christian efforts to find consensus regarding a canon of scripture. Ultimately Proto-orthodox Christian consensus excluded Gnostic books and included the Hebrew scriptures (most often the Greek Septuagint translation of them), but remained elusive regarding some New Testament books, see also Antilegomena. The continued use of the Hebrew scriptures as scripture was a deliberate and significant decision. It was a decision that meant they were accepted as authoritative on matters of doctrine and normative for matters of everyday life.

The word testament, attributed to Tertullian or Marcion[8], is commonly confused with the biblical word covenant, meaning a contract or deal. The Jewish Encyclopedia notes several covenants between God and man in the Tanakh, including: Noah, Abraham, Moses, Aaron and David.[9] It also discusses Jeremiah's prophecy of a "new covenant" (berit hadashah in Hebrew, Jeremiah 31:31) and comments, "Christianity . . . interpreted the words of the prophet in such a way as to indicate a new religious dispensation in place of the law of Moses (Hebrews 8:8-13)."[10]

Christians of all traditions could be cited that would acknowledge the understanding the Jewish Encyclopedia expresses in this article. However, just as the Jewish Encyclopedia acknowledges a series of covenants, that are nonetheless in some sense united, so in fact does ecumenical Christianity, the significant difference being that many Christians believe that some of the covenants, or parts of some covenants, have in some sense been nullified. The term dispensation is common in English language Christian theology in addressing the complicated issues Christians have found in understanding the relationships between the covenants in the Hebrew scriptures, and between those covenants and what the New Testament (often associated with the New Covenant) says about its own relationship to prior covenants (see Dispensationalism).

In covenant theology (a theological framework distinctive of, but not exclusive to, the Reformed churches), the scriptures are interpreted as teaching that God's original purpose was to create for himself one covenant people, which was to be found in the people of Israel in the years before the Messiah, and later expanded to universal salvation through the Messiah.[11] Under this interpretation, old in Old Testament refers to the age before expansion of the covenant through the Messiah and the New Testament present Jesus and his followers as being opposed for preaching this message of gentile (non-Jewish) inclusion.

From the Jewish perspective, the New Testament appropriates parts of Jewish tradition, such as B'nei Noah and Proselyte, to the benefit of Christians, see also Council of Jerusalem. Rabbi Emden noted the following reconciliation[12]:

| “ | ... the original intention of Jesus, and especially of Paul, was to convert only the Gentiles to the seven moral laws of Noah and to let the Jews follow the Mosaic law — which explains the apparent contradictions in the New Testament regarding the laws of Moses and the Sabbath. | ” |

This is a serious matter for believers in both faiths, and a matter that scholars of those faiths often wish to leave out of contention when co-operating on projects of common interest, such as the Dead Sea Scrolls. This is another reason non-confessional terms like Hebrew Bible suit themselves to academic, and other, discourse.

Usage

| Part of a series on The Bible |

||

|---|---|---|

|

||

| Biblical canon and books | ||

| Tanakh: Torah · Nevi'im · Ketuvim Old Testament · Hebrew Bible · New Testament · New Covenant · Deuterocanon · Antilegomena · Chapters & verses Apocrypha: Jewish · OT · NT |

||

| Development and authorship | ||

| Panbabylonism · Jewish Canon · Old Testament canon · New Testament canon · Mosaic authorship · Pauline epistles · Johannine works | ||

| Translations and manuscripts | ||

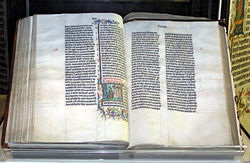

| Septuagint · Samaritan Pentateuch · Dead Sea scrolls · Targums · Peshitta · Vetus Latina · Vulgate · Masoretic text · Gothic Bible · Luther Bible · English Bibles | ||

| Biblical studies | ||

| Dating the Bible · Biblical criticism · Higher criticism · Textual criticism · Novum Testamentum Graece · NT textual categories · Documentary hypothesis · Synoptic problem · Historicity · Internal Consistency · Archeology |

||

| Interpretation | ||

| Hermeneutics · Pesher · Midrash · Pardes · Allegorical · Literalism · Prophecy |

||

| Views | ||

| Inerrancy · Infallibility · Criticism · Islamic · Qur'anic · Gnostic · Judaism and Christianity · Law in Christianity |

||

Using the term Hebrew Bible, then, is an attempt to provide specificity with respect to contents, while avoiding allusion to any particular interpretative tradition or theological school of thought.

On the one hand, the term is not much used among adherents of either Judaism or Christianity. On the other hand, it is widely used in academic writing and interfaith discussion. In short, the term 'Hebrew Bible' is mostly to be found employed in relatively neutral contexts that are meant to include dialogue amongst all religious traditions, but not widely found in the inner discourse of the religions which use its text.

Specific canons

Because "Hebrew Bible" refers to the common portions of the Jewish and Christian biblical canons , it does not encompass the deuterocanonical or apocryphal books, which were preserved in the Greek Septuagint (LXX), and are part of the Old Testament in the canons of the Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches . Thus the term "Hebrew Bible" corresponds most fully to the Old Testament in use by Protestant denominations (adhering to Jerome's Hebraica veritas doctrine), and less fully to canons that are based closely on the Septuagint (adhering to Augustine's 393 Synod of Hippo and 397-419 Councils of Carthage).

Because the term implies a favoritism towards the Masoretic text, however, critics of the Masoretic text also tend to avoid using this term. The Orthodox Church specifically endorses the Septuagint (Greek) text of the Old Testament, not only because they believe it to be more complete, but also because it is most likely the text used by the earliest Christians, appears to be the most widely quoted text in the New Testament, and in many places is more christological than the Masoretic text.

Usage of the term in contexts that refer to the deuterocanonical or apocryphal books, or that refer to the Septuagint text or translations based primarily on the Septuagint text, is thus inaccurate.

See also

- Books of the Bible for the differences between Bible versions of different groups, or the much more detailed Biblical canon.

- Table of books of Judeo-Christian Scripture

- Non-canonical books referenced in the Bible

- Development of the Jewish Bible canon

- Society of Biblical Literature, creators of the SBL Handbook which recommends both standards and alternatives in biblical terminology.

- Masoretic Text, the standard Hebrew text recognized by most Judeo-Christian groups.

- Torah

- Christianity and Judaism

- Biblical law in Christianity

References

- ↑ For a prominent discussion of the term's usage and the motivations for it, see "The New Old Testament" by William Safire, New York Times, 1997-25-5. Also see: Mark Hamilton. "From Hebrew Bible to Christian Bible: Jews, Christians and the Word of God". Retrieved on 2007-11-19. "Modern scholars often use the term 'Hebrew Bible' to avoid the confessional terms Old Testament and Tanakh."

- ↑ Patrick H. Alexander et al., Eds. (1999). The SBL Handbook of Style. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Publishers. pp. p. 17 (section 4.3). ISBN 1-56563-487-X. http://www.sbl-site.org/assets/pdfs/SBLHS.pdf.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 'Marcion', in Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911.

- ↑ For the modern debate, see Biblical law in Christianity

- ↑ [1] DOCTRINE OF THE BIBLE

- ↑ John Joseph Collins, "The Bible After Babel", (2005)

- ↑ 'Marcionites', in Catholic Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Everett Ferguson in chapter 18 of The Canon Debate quotes Tertullian's De praescriptione haereticorum 30: "Since Marcion separated the New Testament from the Old, he is necessarily subsequent to that which he separated, inasmuch as it was only in his power to separate what was previously united. Having been united previous to its separation, the fact of its subsequent separation proves the subsequence also of the man who effected the separation." Note 61 of page 308 adds: "[Wolfram] Kinzig suggests that it was Marcion who usually called his Bible testamentum [Latin for testament]."

- ↑ 'Covenant', in Jewish Encyclopedia, 1906, online link

- ↑ Ibid, The Old and the New Covenant, New Testament

- ↑ Romans 9:6ff; 11:1-7 are often quoted.

- ↑ Gentile: Gentiles May Not Be Taught the Torah

Further reading

- Johnson, Paul (1987). A History of the Jews (First, hardback ed.). London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-79091-9.

- Kuntz, John Kenneth. The People of Ancient Israel: an introduction to Old Testament Literature, History, and Thought, Harper and Row, 1974. ISBN 0-06-043822-3

- Nothing old about it by Shmuley Boteach (Jerusalem Post, November 28, 2007).