Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia

| Haile Selassie I | |

|---|---|

| Emperor of Ethiopia | |

|

|

| Emperor of Ethiopia | |

| Reign | 2 November 1930 – 12 September 1974 (43 years) |

| Predecessor | Zewditu I |

| Successor | De Jure Amha Selassie I (crowned in exile |

| Head of State of Ethiopia | |

| Predecessor | Zewditu I |

| Successor | Aman Mikael Andom (as Chairman of the Derg) |

| Consort | Empress Menen |

| Issue | |

| HIH Romanework Haile Selassie HIH Princess Tenagnework HIM Asfaw Wossen HIH Princess Tsehai HIH Princess Zenebework HIH Prince Makonnen HIH Prince Sahle Selassie |

|

| Titles and styles | |

| Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah, Lord of Lords, King of Kings of Ethiopia and Elect of God | |

| Imperial House | House of Solomon |

| Father | Ras Makonnen Woldemikael Gudessa |

| Mother | Weyziro Yeshimebet Ali Abajifar |

| Born | 23 July 1892 Ejersa Goro, Harar |

| Died | 27 August 1975 (aged 83) |

| Religious faiths | Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Christian |

| Main doctrines | |

| Jah · Afrocentrism · Ital · Zion · Spiritual use of cannabis | |

| Central figures | |

|

Jesus Christ · Haile Selassie |

|

| Key scriptures | |

| Bible · Kebra Nagast The Promise Key · Holy Piby My Life and Ethiopia's Progress |

|

| Branches and festivals | |

| Mansions · United States Shashamane · Grounation Day |

|

| Notable individuals | |

| Bob Marley · Walter Rodney | |

| See also: | |

| Vocabulary · Persecution · Dreadlocks · Reggae Ethiopian Christianity Index of Rastafari articles |

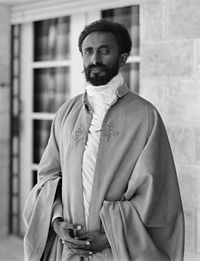

Haile Selassie I (Ge'ez: ኃይለ፡ ሥላሴ, "Power of the Trinity";[1] 23 July 1892 – 27 August 1975), born Tafari Makonnen, was Ethiopia's regent from 1916 to 1930 and Emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974. The heir to a dynasty that traced its origins to the 13th century, and from there by tradition back to King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, Haile Selassie is a defining figure in both Ethiopian and African history.[2][3]

At the League of Nations in 1936, the Emperor's condemnation of the use of chemical weapons against his people was a pivotal moment in the onset of the Second World War, as well as a foreshadowing of the "barbarism" which was to come.[4] His internationalist views led to Ethiopia's becoming a charter member of the United Nations, and his political thought and experience in promoting multilateralism and collective security have proved seminal and enduring.[5] His suppressing of rebellions among the nobles (mekwannint), as well as what some perceived to be Ethiopia's failure to modernize adequately,[6] earned him criticism among some contemporaries and historians.[7]

Haile Selassie is revered as the religious symbol for God incarnate among the Rastafari movement, which numbers approximately 600,000.[8] Begun in Jamaica in the 1930s, the Rastafari movement perceives Haile Selassie as a messianic figure who will lead the peoples of Africa and the African diaspora to a golden age of peace, righteousness, and prosperity.[9]

Contents |

Name

Haile Selassie I was born Lij Tafari Makonnen (Ge'ez ልጅ፡ ተፈሪ፡ መኮንን; Amharic pronunciation lij teferī mekōnnin). "Lij" translates literally to "child", and serves to indicate that a youth is of noble blood. He would later become Ras Tafari Mekonnen; "Ras" translates literally to "head"[10] and is the equivalent of "duke",[11] though it is often rendered in translation as "prince". In 1928, he was elevated to Negus, "King".

Upon his ascension to Emperor in 1930, he took the name Haile Selassie, meaning "Power of the Trinity".[12] Haile Selassie's full title in office was "His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I, Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah, King of Kings of Ethiopia and Elect of God" (Ge'ez ግርማዊ፡ ቀዳማዊ፡ አፄ፡ ኃይለ፡ ሥላሴ፡ ሞዓ፡ አንበሳ፡ ዘእምነገደ፡ ይሁዳ፡ ንጉሠ፡ ነገሥት፡ ዘኢትዮጵያ፡ ሰዩመ፡ እግዚአብሔር; girmāwī ḳadāmāwī 'aṣē ḫāylē śillāsē, mō'ā 'anbassā za'imnaggada yīhūda nigūsa nagast za'ītyōṗṗyā, siyūma 'igzī'a'bihēr). This title reflects Ethiopian dynastic traditions, which hold that all monarchs must trace their lineage back to Menelik I, who in the Ethiopian tradition was the offspring of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba.[13]

To Ethiopians Haile Selassie has been known by many names, including Janhoy, Talaqu Meri, and Abba Tekel. The Rastafari employ many of these appellations, also referring to him as HIM, Jah and Jah Rastafari.

Biography

Early life

Haile Selassie I was born Tafari Makonnen from a mixed Oromo, Amhara, and Gurage[14] family on 23 July 1892, in the village of Ejersa Goro, in the Harar province of Ethiopia. His mother was Woizero ("Lady") Yeshimebet Ali Abajifar. His father was Ras Makonnen Woldemikael Gudessa, the governor of Harar; Ras Makonnen served as a general in the First Italo–Ethiopian War, playing a key role at the Battle of Adwa.[15] He inherited his imperial blood through his paternal grandmother, Princess Tenagnework Sahle Selassie, who was an aunt of Emperor Menelik II, and as such asserted direct descent from Makeda, the Queen of Sheba, and King Solomon of ancient Israel.[16]

Ras Makonnen arranged for Tafari as well as his first cousin, Ras Imru Haile Selassie to receive instruction in Harar from Abba Samuel Wolde Kahin, an Ethiopian capuchin monk, and from Dr. Vitalien, a surgeon from Guadeloupe. Tafari was named Dejazmach (literally "commander of the gate", roughly equivalent to "count")[17] at the age of 13, on 1 November 1905.[18] Shortly thereafter, his father Ras Makonnen died at Kulibi, in 1906.[19]

Governorship

Tafari assumed the titular governorship of Selale in 1906, a realm of marginal importance[20] but one that enabled him to continue his studies.[18] In 1907, he was appointed governor over part of the province of Sidamo. It is alleged that during his late teens, Haile Selassie was married to Woizero Altayech, and that from this union, his daughter Romanework Haile Selassie was born.[21][22]

Following the death of his brother Yelma in 1907, the governorate of Harar was left vacant,[20] and its administration was left to Menelik's loyal general, Dejazmach Balcha Safo. Balcha Safo's administration of Harar was ineffective, and so during the last illness of Menelik II, and the brief reign of Empress Taitu Bitul, Tafari was made governor of Harar in 1910[19] or 1911.[14]

On 3 August he married Menen Asfaw of Ambassel, niece of heir to the throne Lij Iyasu.

Regency

The extent to which Tafari contributed to the movement that would come to depose Iyasu V is unclear. Iyasu V, or Lij Iyasu, was the designated but uncrowned Emperor of Ethiopia from 1913 to 1916. Iyasu's reputation for scandalous behavior and a disrespectful attitude to the nobles at his grandfather Menelik II's court[23] damaged his reputation, and his flirtation with Islam was considered treasonous among the Ethiopian Orthodox Christian leadership of the empire, leading to his being deposed on 27 September 1916.[24]

Contributing to the movement that deposed Iyasu were conservatives such as Fitawrari Habte Giorgis Dinagde, Menelik II's longtime war minister. The movement to depose Iyasu preferred Tafari, as he attracted support from both progressive and conservative factions. Ultimately, Iyasu was deposed on the grounds of conversion to Islam,[10][24] and Menelik II's daughter (Iyasu's aunt) was named Empress Zewditu. Tafari was elevated to the rank of Ras and was made heir apparent. In the power arrangement that followed, Tafari accepted the role of Regent (Inderase) and became the de facto ruler of the Ethiopian Empire.

As regent, the new Crown Prince developed the policy of cautious modernization initiated by Menelik II. He secured Ethiopia's admission to the League of Nations in 1923 by promising to eradicate slavery; each emperor since Tewodros II had issued proclamations to halt slavery,[25] but without effect: the internationally-scorned practice persisted well into Haile Selassie's reign.[26] He toured Europe that same year, inspecting schools, hospitals, factories, and churches. Although patterning many reforms after European models, he remained wary of European pressure. To guard against economic imperialism, he required that all enterprises have at least partial local ownership.[27] Of his modernization campaign, he remarked, "We need European progress only because we are surrounded by it. That is at once a benefit and a misfortune."[28]

Throughout Ras Tafari's travels in Europe, the Levant, and Egypt, he and his entourage were greeted with enthusiasm and fascination. He was accompanied by two other Rases, each of whom was also the son of a general who had contributed to the victorious war against Italy a quarter century earlier.[29] The Ethiopians' "Oriental Dignity"[30] and "rich, picturesque court dress"[31] were sensationalized in the media; among his entourage he even included a pride of lions, which he distributed as gifts to President Poincaré of France, George V of the United Kingdom, and the Zoological Garden of Paris.[29] As one historian noted, "Rarely can a tour have inspired so many anecdotes".[29]

In this period, the Crown Prince visited the Armenian monastery of Jerusalem. There, he adopted 40 Armenian orphans (አርባ ልጆች Arba Lijoch, "forty children") who had escaped the Armenian genocide of the Ottoman Empire.[32] The prince arranged for the musical education of the youths, and they came to form the imperial brass band.[33]

King and Emperor

Tafari's authority was challenged in 1928 when veteran General Balcha Safo marched on Addis Ababa. The general paid homage to the Empress, but snubbed Tafari.[34] The gesture empowered Empress Zewditu politically, and she attempted to have Tafari tried for treason, for his benevolent dealings with Italy, which included a 20-year peace accord (see Italo–Ethiopian Treaty of 1928).[18] When popular support, as well as the support of the police,[34] seemed to remain with Tafari, the Empress relented and crowned him Negus (Amharic: "King") in 1928.

The crowning of Tafari was controversial, as he occupied the same territory as the Empress, rather than going off to a regional kingdom of the empire. Two monarchs, even with one being the vassal and the other the Emperor (in this case Empress), had never occupied the same location as their seat in Ethiopian history. Conservatives, including Balcha Safo, agitated to redress this perceived insult to the dignity of the crown, leading to the rebellion of Ras Gugsa Welle, husband of the Empress. He marched from his governorate at Gondar towards Addis Ababa but was defeated and killed at the Battle of Anchim in March 1930.[35] News of Gugsa Wele's defeat and death had hardly spread through Addis Ababa when the Empress died suddenly on 2 April 1930. Although it was long rumored that the Empress was poisoned upon the defeat of her husband,[36] or alternately that she died from shock upon hearing of the death of her estranged yet beloved husband,[37] it has since been documented that the Empress succumbed to a flu-like fever and complications from diabetes.[38]

With the passing of Zewditu, Tafari himself rose to Emperor and was proclaimed Neguse Negest ze-'Ityopp'ya, "King of Kings of Ethiopia". He was crowned on 2 November 1930, at Addis Ababa's Cathedral of St. George. The coronation was by all accounts "a most splendid affair",[39] and it was attended by royals and dignitaries from all over the world. Among those in attendance were George V's son Prince Henry, Marshal Franchet d'Esperey of France, and the Prince of Udine representing Italy. Emissaries from the United States,[40] Egypt, Turkey, Sweden, Belgium, and Japan were also present.[39] British author Evelyn Waugh was also present, penning a contemporary report on the event. One newspaper report suggested that the celebration may have incurred a cost in excess of $3,000,000.[41] Many of those in attendance received lavish gifts;[42] in one instance, the Christian Emperor even sent a gold-encased Bible to an American bishop who had not attended the coronation, but who had dedicated a prayer to the Emperor on the day of the coronation.[43]

Haile Selassie introduced Ethiopia's first written constitution on 16 July 1931,[44] providing for a bicameral legislature.[45] The constitution kept power in the hands of the nobility, but it did establish democratic standards among the nobility, envisaging a transition to democratic rule: it would prevail "until the people are in a position to elect themselves."[45] The constitution limited the succession to the throne to the descendants of Haile Selassie, a point that met with the disapprobation of other dynastic princes, including the princes of Tigrai and even the Emperor's loyal cousin, Ras Kassa Haile Darge.

In 1932, the Kingdom of Jimma was formally absorbed into Ethiopia following the death of King Abba Jifar II of Jimma.

Conflict with Italy

- See also: Abyssinia Crisis and Second Italo-Abyssinian War

Ethiopia became the target of Italian imperialist designs in the 1930s. Mussolini's fascist regime was keen to avenge the military defeats Italy had suffered to Ethiopia in the First Italo-Abyssinian War.[46][47] A conquest of Ethiopia could also empower the cause of fascism and embolden its rhetoric of empire.[47] Ethiopia would also provide a bridge between Italy's Eritrean and Italian Somaliland possessions. Ethiopia's position in the League of Nations did not dissuade the Italians from invading in 1935; the "collective security" envisaged by the League proved useless, and a scandal erupted when the Hoare-Laval Pact revealed that Ethiopia's League allies were scheming to appease Italy.[48]

Mobilization

Following the 1935 Italian invasion of Ethiopia, Haile Selassie joined his northern armies and set up headquarters at Desse in Wollo province. He issued his famous mobilization order on 3 October 1935:

| “ | If you withhold from your country Ethiopia the death from cough or head-cold of which you would otherwise die, refusing to resist (in your district, in your patrimony, and in your home) our enemy who is coming from a distant country to attack us, and if you persist in not shedding your blood, you will be rebuked for it by your Creator and will be cursed by your offspring. Hence, without cooling your heart of accustomed valour, there emerges your decision to fight fiercely, mindful of your history that will last far into the future... If on your march you touch any property inside houses or cattle and crops outside, not even grass, straw, and dung excluded, it is like killing your brother who is dying with you... You, countryman, living at the various access routes, set up a market for the army at the places where it is camping and on the day your district-governor will indicate to you, lest the soldiers campaigning for Ethiopia's liberty should experience difficulty. You will not be charged excise duty, until the end of the campaign, for anything you are marketing at the military camps: I have granted you remission... After you have been ordered to go to war, but are then idly missing from the campaign, and when you are seized by the local chief or by an accuser, you will have punishment inflicted upon your inherited land, your property, and your body; to the accuser I shall grant a third of your property . . . . | ” |

On 19 October 1935, Haile Selassie gave more precise orders for his army to his Commander-in-Chief, Ras Kassa:

- When you set up tents, it is to be in caves and by trees and in a wood, if the place happens to be adjoining to these―and separated in the various platoons. Tents are to be set up at a distance of 30 cubits from each other.

- When an aeroplane is sighted, one should leave large open roads and wide meadows and march in valleys and trenches and by zigzag routes, along places which have trees and woods.

- When an aeroplane comes to drop bombs, it will not suit it to do so unless it comes down to about 100 metres; hence when it flies low for such action, one should fire a volley with a good and very long gun and then quickly disperse. When three or four bullets have hit it, the aeroplane is bound to fall down. But let only those fire who have been ordered to shoot with a weapon that has been selected for such firing, for if everyone shoots who possesses a gun, there is no advantage in this except to waste bullets and to disclose the men's whereabouts.

- Lest the aeroplane, when rising again, should detect the whereabouts of those who are dispersed, it is well to remain cautiously scattered as long as it is still fairly close. In time of war it suits the enemy to aim his guns at adorned shields, ornaments, silver and gold cloaks, silk shirts and all similar things. Whether one possesses a jacket or not, it is best to wear a narrow-sleeved shirt with faded colours. When we return, with God's help, you can wear your gold and silver decorations then. Now it is time to go and fight. We offer you all these words of advice in the hope that no great harm should befall you through lack of caution. At the same time, We are glad to assure you that in time of war We are ready to shed Our blood in your midst for the sake of Ethiopia's freedom..."[49]

Compared to the Ethiopians, the Italians had an advanced, modern military which included a large air force. The Italians would also come to employ chemical weapons extensively throughout the conflict, even targeting Red Cross field hospitals in violation of the Geneva Convention.[50]

Progress of the war

Starting in early October 1935, the Italians invaded Ethiopia. On 6 October, Italian honor was avenged when Adwa fell. But, by November, the pace of invasion had slowed appreciably and Haile Selassie's northern armies were able to launch what was known as the "Christmas Offensive." During this offensive, the Italians were forced back in places and put on the defensive. However, by early in 1936, the First Battle of Tembien stopped the progress of the Ethiopian offensive and the Italians were ready to continue their offensive. Following the defeat and destruction of the northern Ethiopian armies at the Battle of Amba Aradam, the Second Battle of Tembien, and the Battle of Shire, Haile Selassie took the field with the last Ethiopian army on the northern front. On 31 March 1936, he launched a counterattack against the Italians himself at the Battle of Maychew in southern Tigray. The Emperor's army was defeated and retreated in disarray. As Haile Selassie's army withdrew, the Italians attacked from the air along with rebellious Raya and Azebo tribesmen on the ground, who were armed and paid by the Italians.[51]

Haile Selassie made a solitary pilgrimage to the churches at Lalibela, at considerable risk of capture, before returning to his capital.[53] After a stormy session of the council of state, it was agreed that because Addis Ababa could not be defended, the government would relocate to the southern town of Gore, and that in the interest of preserving the Imperial house, the Emperor's wife Menen Asfaw and the rest of the Imperial family should immediately depart for Djibouti, and from there continue on to Jerusalem.

Exile debate

After further debate as to whether Haile Selassie should go to Gore or accompany his family into exile, it was agreed that Haile Selassie should leave Ethiopia with his family and present the case of Ethiopia to the League of Nations at Geneva. The decision was not unanimous and several participants, including the nobleman Blatta Tekle Wolde Hawariat, objected to the idea of an Ethiopian monarch fleeing before an invading force.[54] Haile Selassie appointed his cousin Ras Imru Haile Selassie as Prince Regent in his absence, departing with his family for Djibouti on 2 May 1936.

On 5 May, Marshal Pietro Badoglio led Italian troops into Addis Ababa, and Mussolini declared Ethiopia an Italian province. Victor Emanuel III was proclaimed as the new Emperor of Ethiopia. However, on 4 May, the day before, the Ethiopian exiles had left Djibouti aboard the British cruiser HMS Enterprise. They were bound for Jerusalem in the British Mandate of Palestine, where the Ethiopian royal family maintained a residence. The Imperial family disembarked at Haifa and then went on to Jerusalem. Once there, Haile Selassie and his retinue prepared to make their case at Geneva. The choice of Jerusalem was highly symbolic, since the Solomonic Dynasty claimed descent form the House of David. Leaving the Holy Land, Haile Selassie and his entourage sailed for Gibraltar aboard the British cruiser HMS Capetown. From Gibraltar, the exiles were transferred to an ordinary liner. By doing this, the government of the United Kingdom was spared the expense of a state reception.[55]

Collective security and The League of Nations, 1936

Mussolini, upon invading Ethiopia, had promptly declared his own "Italian Empire"; because the League of Nations afforded Haile Selassie the opportunity to address the assembly, Italy even withdrew its League delegation, on 12 May 1936.[56] It was in this context that Haile Selassie walked into the hall of the League of Nations, introduced by the President of the Assembly as "His Imperial Majesty, the Emperor of Ethiopia" (Sa Majesté Imperiale, l'Empereur d'Ethiopie). The introduction caused a great many Italian journalists in the galleries to erupt into jeering, heckling, and whistling. As it turned out, they had earlier been issued whistles by Mussolini's son-in-law, Count Galeazzo Ciano.[57] Haile Selassie waited calmly for the hall to be cleared, and responded "majestically"[58] with a speech often considered among the most stirring of the twentieth century.

Although fluent in French, the working language of the League, Haile Selassie chose to deliver his historic speech in his native Amharic. He asserted that, because his "confidence in the League was absolute", his people were now being slaughtered. He pointed out that the same European states that found in Ethiopia's favor at the League of Nations were refusing Ethiopia credit and war matériel while aiding Italy, which was employing chemical weapons on military and civilian targets alike.

It was at the time when the operations for the encircling of Makale were taking place that the Italian command, fearing a rout, followed the procedure which it is now my duty to denounce to the world. Special sprayers were installed on board aircraft so that they could vaporize, over vast areas of territory, a fine, death-dealing rain. Groups of nine, fifteen, eighteen aircraft followed one another so that the fog issuing from them formed a continuous sheet. It was thus that, as from the end of January 1936, soldiers, women, children, cattle, rivers, lakes, and pastures were drenched continually with this deadly rain. In order to kill off systematically all living creatures, in order to more surely poison waters and pastures, the Italian command made its aircraft pass over and over again. That was its chief method of warfare.[59]

Noting that his own "small people of 12 million inhabitants, without arms, without resources" could never withstand an attack by a large power such as Italy, with its 42 million people and "unlimited quantities of the most death-dealing weapons", he contended that all small states were threatened by the aggression, and that all small states were in effect reduced to vassal states in the absence of collective action. He admonished the League that "God and history will remember your judgment."[60]

It is collective security: it is the very existence of the League of Nations. It is the confidence that each State is to place in international treaties... In a word, it is international morality that is at stake. Have the signatures appended to a Treaty value only in so far as the signatory Powers have a personal, direct and immediate interest involved?

The speech made the Emperor an icon for anti-Fascists around the world, and Time Magazine named him "Man of the Year."[61] He failed, however, to get what he most needed: the League agreed to only partial and ineffective sanctions on Italy, and several members even recognized the Italian conquest.[46]

Exile

Haile Selassie spent his exile years (1936–1941) in Bath, United Kingdom, in Fairfield House, which he bought. His activity in this period was focused on countering Italian propaganda as to the state of Ethiopian resistance and the legality of the occupation.[62] He spoke out against the desecration of houses of worship and historical artifacts (including the theft of a 1,600-year old imperial obelisk), and condemned the atrocities suffered by the Ethiopian civilian population.[63] He continued to plead for League intervention and to voice his certainty that "God's judgment will eventually visit the weak and the mighty alike",[64] though his attempts to gain support for the struggle against Italy were largely unsuccessful until Italy entered World War II on the German side in June 1940.[65]

The Emperor's pleas for international support did take root in the United States, particularly among African American organizations sympathetic to the Ethiopian cause.[66] In 1937, Haile Selassie was to give a Christmas Day radio address to the American people to thank his supporters when his taxi was involved in a traffic accident, leaving him with a fractured knee.[67] Rather than canceling the radio appearance, he proceeded in much pain to complete the address, in which he linked Christianity and goodwill with the Covenant of the League of Nations, and asserted that "War is not the only means to stop war":[67]

With the birth of the Son of God, an unprecedented, an unrepeatable, and a long-anticipated phenomenon occurred. He was born in a stable instead of a palace, in a manger instead of a crib. The hearts of the Wise men were struck by fear and wonder due to His Majestic Humbleness. The kings prostrated themselves before Him and worshipped Him. 'Peace be to those who have good will'. This became the first message.

[...] Although the toils of wise people may earn them respect, it is a fact of life that the spirit of the wicked continues to cast its shadow on this world. The arrogant are seen visibly leading their people into crime and destruction. The laws of the League of Nations are constantly violated and wars and acts of aggression repeatedly take place... So that the spirit of the cursed will not gain predominance over the human race whom Christ redeemed with his blood, all peace loving people should cooperate to stand firm in order to preserve and promote lawfulness and peace.[67]

During this period, Haile Selassie suffered several personal tragedies. His two sons-in-law, Ras Desta Damtew and Dejazmach Beyene Merid, were both executed by the Italians.[64] The Emperor's daughter, Princess Romanework, wife of Dejazmach Beyene Merid, was herself taken into captivity with her children, and she died in Italy in 1941.[68] His daughter Tsehai died during childbirth shortly after the restoration in 1942.[69]

After his return to Ethiopia, he donated Fairfield House to the city of Bath as a residence for the aged, and it remains so to this day.[70]

1940s and 1950s

British forces, which consisted primarily of Ethiopian-backed African and South African colonial troops under the "Gideon Force" of Colonel Orde Wingate, coordinated the military effort to liberate Ethiopia. The Emperor himself issued several imperial proclamations in this period, demonstrating that, while authority was not divided up in any formal way, British military might and the Emperor's populist appeal could be joined in the concerted effort to liberate Ethiopia.[65]

On 18 January 1941, during the East African Campaign, Haile Selassie crossed the border between Sudan and Ethiopia near the village of Um Iddla. The standard of the Lion of Judah was raised again. Two days later, he and a force of Ethiopian patriots joined Gideon Force which was already in Ethiopia and preparing the way.[71] Italy was defeated by a force of the United Kingdom, the Commonwealth of Nations, Free France, Free Belgium, and Ethiopian patriots. On 5 May 1941, Haile Selassie entered Addis Ababa and personally addressed the Ethiopian people, five years to the day since his 1936 exile:

Today is the day on which we defeated our enemy. Therefore, when We say let us rejoice with our hearts, let not our rejoicing be in any other way but in the spirit of Christ. Do not return evil for evil. Do not indulge in the atrocities which the enemy has been practicing in his usual way, even to the last.

Take care not to spoil the good name of Ethiopia by acts which are worthy of the enemy. We shall see that our enemies are disarmed and sent out the same way they came. As St. George who killed the dragon is the Patron Saint of our army as well as of our allies, let us unite with our allies in everlasting friendship and amity in order to be able to stand against the godless and cruel dragon which has newly risen and which is oppressing mankind.[72]

After World War II, Ethiopia became a charter member of the United Nations. In 1948, the Ogaden, a region disputed with Somalia, was granted to Ethiopia.[73] On 2 December 1950, the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution 390 (V), establishing the federation of Eritrea (the former Italian colony) into Ethiopia.[74] Eritrea was to have its own constitution, which would provide for ethnic, linguistic, and cultural balance, while Ethiopia was to manage its finances, defense, and foreign policy.[74]

Despite his centralization policies that had been made before World War II, Haile Selassie still found himself unable to push for all the programs he wanted. In 1942, he attempted to institute a progressive tax scheme, but this failed due to opposition from the nobility, and only a flat tax was passed; in 1951, he agreed to reduce this as well.[75] Ethiopia was still "semi-feudal",[76] and the Emperor's attempts to alter its social and economic form by reforming its modes of taxation met with resistance from the nobility and clergy, which were eager to resume their privileges in the postwar era.[75] Where Haile Selassie actually did succeed in effecting new land taxes, the burdens were often passed by the landowners to the peasants.[75] Despite his wishes, the tax burden remained primarily on the peasants.

Between 1941 and 1959, Haile Selassie worked to establish the autocephaly of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.[77] The Ethiopian Orthodox Church had been headed by the abuna, a bishop who answered to the Partriarchate in Egypt. Haile Selassie applied to Egypt's Holy Synod in 1942 and 1945 to establish the independence of Ethiopian bishops, and when his appeals were denied he threatened to sever relations with the See of St. Mark.[77] Finally, in 1959, Pope Kyrillos VI elevated the Abuna to Patriarch-Catholicos.[77] The Ethiopian Church remained affiliated with the Alexandrian Church.[75] In addition to these efforts, Haile Selassie changed the Ethiopian church-state relationship by introducing taxation of church lands, and by restricting the legal privileges of the clergy, who had formerly been tried in their own courts for civil offenses.[75]

In keeping with the principle of collective security, for which he was an outspoken proponent, he sent a contingent under General Mulugueta Bulli, known as the Kagnew Battalion, to take part in the UN Conflict in Korea. It was attached to the American 7th Infantry Division, and fought in a number of engagements including the Battle of Pork Chop Hill.[78] In a 1954 speech, the Emperor spoke of Ethiopian participation in the Korean conflict as a redemption of the principles of collective security:

Nearly two decades ago, I personally assumed before history the responsibility of placing the fate of my beloved people on the issue of collective security, for surely, at that time and for the first time in world history, that issue was posed in all its clarity. My searching of conscience convinced me of the rightness of my course and if, after untold sufferings and, indeed, unaided resistance at the time of aggression, we now see the final vindication of that principle in our joint action in Korea, I can only be thankful that God gave me strength to persist in our faith until the moment of its recent glorious vindication.[79]

During the celebrations of his Silver Jubilee in November 1955, Haile Selassie introduced a revised constitution,[80] whereby he retained effective power, while extending political participation to the people by allowing the lower house of parliament to become an elected body. Party politics were not provided for. Modern educational methods were more widely spread throughout the Empire, and the country embarked on a development scheme and plans for modernization, tempered by Ethiopian traditions, and within the framework of the ancient monarchical structure of the state.

Haile Selassie compromised when practical with the traditionalists in the nobility and church. He also tried to improve relations between the state and ethnic groups, and granted autonomy to Afar lands that were difficult to control. Still, his reforms to end feudalism were slow and weakened by the compromises he made with the entrenched aristocracy. The Revised Constitution of 1955 has been criticized for reasserting "the indisputable power of the monarch" and maintaining the relative powerlessness of the peasants.[81]

His international fame and acceptance also grew. In 1954 he visited West Germany, becoming the first head of state to do so after the end of World War II. Many elderly Germans still vividly recall the Emperor's visit, as it signaled their acceptance back into the world, as a peaceful nation. He donated blankets produced by the Debre Birhan Blanket Factory, in Ethiopia, to the war-ravaged German people.

1960s

Haile Selassie contributed Ethiopian troops to the United Nations Operation in the Congo peacekeeping force during the 1960 Congo Crisis, to consolidate Congolese integrity and independence from Belgian troops, per United Nations Security Council Resolution 143. On 13 December 1960, while Haile Selassie was on a state visit to Brazil, his Imperial Guard forces staged an unsuccessful coup attempt, briefly proclaiming Haile Selassie's eldest son Asfa Wossen as Emperor. The coup d'état was crushed by the regular Army and police forces. The coup attempt lacked broad popular support, was denounced by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, and was unpopular among the Army, Air and Police forces. Nonetheless, the effort to depose the Emperor had support among students and the educated classes.[82] The coup attempt has been characterized as a pivotal moment in Ethiopian history, the point at which Ethiopians "for the first time questioned the power of the king to rule without the people's consent."[83] Student populations began to empathize with the peasantry and poor, and to advocate on their behalf.[83] The coup spurred Haile Selassie to accelerate reform, which manifested in the form of land grants to military and police officials.

The Emperor continued to be a staunch ally of the West, while pursuing a firm policy of decolonization in Africa, which was still largely under European colonial rule. The United Nations conducted a lengthy inquiry regarding the status of Eritrea, with the superpowers each vying for a stake in the state's future. Britain, the administrator at the time, suggested the partition of Eritrea between Sudan and Ethiopia, separating Christians and Muslims. The idea was instantly rejected by Eritrean political parties, as well as the UN.

A United Nations plebiscite voted 46 to 10 to have Eritrea be federated with Ethiopia, which was later stipulated on 2 December 1950 in resolution 390 (V). Eritrea would have its own parliament and administration and would be represented in what had been the Ethiopian parliament and would become the federal parliament.[84] However, Haile Selassie would have none of European attempts to draught a separate Constitution under which Eritrea would be governed, and wanted his own 1955 Constitution protecting families to apply in both Ethiopia and Eritrea. In 1961 the 30-year Eritrean Struggle for Independence began, followed by Haile Selassie's dissolution of the federation and shutting down of Eritrea's parliament.

In 1961, tensions between independence-minded Eritreans and Ethiopian forces culminated in the Eritrean War of Independence. The Emperor declared Eritrea the fourteenth province of Ethiopia in 1962.[85] The war would continue for 30 years, as first Haile Selassie, then the Soviet-backed junta that succeeded him, attempted to retain Eritrea by force.

In 1963, Haile Selassie presided over the establishment of the Organisation of African Unity, with the new organization establishing its headquarters in Addis Ababa. As more African states won their independence, he played an important role as Pan-Africanist, and along with Modibo Keïta of Mali was successful in negotiating the Bamako Accords, which brought an end to the border conflict between Morocco and Algeria.

In 1966, Haile Selassie attempted to create a modern, progressive tax that included registration of land, which would significantly weaken the nobility. Even with alterations, this law led to a revolt in Gojam, which was repressed although enforcement of the tax was abandoned. The revolt, having achieved its design in undermining the tax, encouraged other landowners to defy Haile Selassie.

Student unrest became a regular feature of Ethiopian life in the 1960s and 1970s. Marxism took root in large segments of the Ethiopian intelligentsia, particularly among those who had studied abroad and had thus been exposed to radical and left-wing sentiments that were becoming fashionable in other parts of the globe.[82] Resistance by conservative elements at the Imperial Court and Parliament, and by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, made Haile Selassie's land reform proposals difficult to implement, and also damaged the standing of the government, costing Haile Selassie much of the goodwill he had once enjoyed. This bred resentment among the peasant population. Efforts to weaken unions also hurt his image. As these issues began to pile up, Haile Selassie left much of domestic governance to his Prime Minister, Aklilu Habte Wold, and concentrated more on foreign affairs.

1970s

Outside of Ethiopia, Haile Selassie continued to enjoy enormous prestige and respect. As the longest serving Head of State in power, Haile Selassie was often given precedence over other leaders at state events, such as the state funerals of John F. Kennedy and Charles de Gaulle, the summits of the Non-Aligned Movement, and the 1971 celebration of the 2,500 years of the Persian Empire. His high profile and frequent travels around the world raised Ethiopia's international image.

Wollo Famine

Famine mostly in Wollo, northeastern Ethiopia, as well as in some parts of Tigray is estimated to have killed 40,000 to 80,000 Ethiopians[7][86] between 1972-74.[87] Although the region is infamous for recurrent crop failures and continuous food shortage and starvation risk, this episode was remarkably severe. It led to the 1973 production of the BBC program "The Unknown Famine" by Jonathan Dimbleby.[88][89] Dimbleby's report suggested a far higher death toll than was borne out by the facts,[90] stimulating a massive influx of aid while at the same time destabilizing Haile Selassie's regime.[86]

Some reports suggest that the Emperor was unaware of the extent of the famine,[91] while others assert that he was well aware of it.[92][93] In addition to the exposure of attempts by corrupt local officials to cover up the famine from the Imperial government, the media's depiction of Haile Selassie's Ethiopia as backwards and inept (relative to the purported utopia of Marxism-Leninism) contributed to the popular uprising that led to its downfall and the rise of Mengistu Haile Mariam.[94] The famine and its image in the media undermined popular support of the government, and Haile Selassie's once unassailable personal popularity fell.

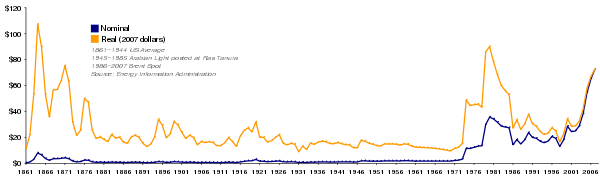

The crisis was exacerbated by military mutinies and high oil prices, the latter a result of the 1973 oil crisis. The international economic crisis triggered by the oil crisis caused the costs of imported goods, gasoline, and food to skyrocket, while unemployment spiked.[81]

Revolution

In February 1974, four days of serious riots in Addis against a sudden economic inflation left five dead. The Emperor responded by announcing on national television a rollback of gasoline prices and a freeze on the cost of basic commodities. This calmed the public, but the promised 33% military wage hike was not substantial enough to pacify the army, which then mutinied, beginning in Asmara and spreading throughout the empire. This mutiny led to the resignation of Prime Minister Aklilu Habte Wold on 27 February 1974.[95] Haile Selassie again went on television to agree to the army's demands for still greater pay, and named Endalkatchew Makonnen as his new Prime Minister. However, despite Endalkatchew's many concessions, discontent continued in March with a four-day general strike that paralyzed the nation.

The Derg, a committee of low-ranking military officers and enlisted men, set up in June to investigate the military's demands, took advantage of the government's disarray to depose Haile Selassie on 12 September 1974. General Aman Mikael Andom, a Protestant of Eritrean origin,[95] served briefly as provisional head of state pending the return of Crown Prince Asfa Wossen, who was then receiving medical treatment abroad. Haile Selassie was placed under house arrest briefly at the 4th Army Division in Addis Ababa,[95] while most of his family was detained at the late Duke of Harrar's residence in the north of the capital. The last months of the Emperor's life were spent in imprisonment, in the Grand Palace.[96]

Later, most of the Imperial family was imprisoned in the Addis Ababa prison known as "Alem Bekagn", or "I am finished with the world". On 23 November 1974, 60 former high officials of the Imperial government, known as "the Sixty", were executed without trial.[97] The executed included Haile Selassie's grandson and two former Prime Ministers.[96] These killings, known to Ethiopians as "Bloody Saturday", were condemned by Crown Prince Asfa Wossen; the Derg responded to his rebuke by revoking its acknowledgment of his imperial legitimacy, and announcing the end of the Solomonic dynasty.[97]

Death and interment

On 28 August 1975, the state media officially reported publicly that the "ex-monarch" Haile Selassie had died on 27 August of "respiratory failure" following complications from a prostate operation.[98] His doctor, Asrat Woldeyes, denied that complications had occurred and rejected the government version of his death. Some imperial loyalists believed that the Emperor had in fact been assassinated, and this belief remains widely held.[99] One western correspondent in Ethiopia at the time commented, "While it is not known what actually happened, there are strong indications that no efforts were made to save him. It is unlikely that he was actually killed. Such rumors were bound to arise no matter what happened, given the atmosphere of suspicion and distrust prevailing in Addis Ababa at the time."[100]

The Soviet-backed Derg fell in 1991. In 1992, the Emperor's bones were found under a concrete slab on the palace grounds;[99] some reports suggest that his remains were discovered beneath a latrine.[101] For almost a decade thereafter, as Ethiopian courts attempted to sort out the circumstances of his death, his coffin rested in Bhata Church, near his great uncle Menelik II's imperial resting place.[102] On 5 November 2000, Haile Selassie was given an Imperial funeral by the Ethiopian Orthodox church. The post-communist government refused calls to declare the ceremony an official imperial funeral.[102]

Although such prominent Rastafari figures as Rita Marley and others participated in the grand funeral, most Rastafari rejected the event and refused to accept that the bones were the remains of Haile Selassie. There remains some debate within the Rastafari movement as to whether Haile Selassie actually died in 1975.[103]

Children

By Menen Asfaw, Haile Selassie had six children: Princess Tenagnework, Crown Prince Asfaw Wossen, Princess Tsehai, Princess Zenebework, Prince Makonnen, and Prince Sahle Selassie.

There is some controversy as to Haile Selassie's eldest daughter, Princess Romanework Haile Selassie. While the living members of the royal family state that Romanework is the eldest daughter of Empress Menen,[104] it has been asserted that Princess Romanework is actually the daughter of a previous union of the emperor with Woizero Altayech.[105] The emperor's own autobiography makes no mention of a previous marriage or having fathered children with anyone other than Empress Menen.

The Rastafari Messiah

Today, Haile Selassie is worshipped as the God[106] incarnate among followers of the Rastafari movement (taken from Haile Selassie's pre-imperial name Ras — meaning Head - a title equivalent to Duke — Tafari Makonnen), which emerged in Jamaica during the 1930s under the influence of Marcus Garvey's "Pan Africanism" movement, and as the Messiah who will lead the peoples of Africa and the African diaspora to freedom.[107] His official titles, Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah, King of Kings and Elect of God, and his traditional lineage from Solomon and Sheba,[108] are perceived by Rastafarians as confirmation of the return of the Messiah in the prophetic Book of Revelation in the New Testament: King of Kings, Lord of Lords, Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah and Root of David. Rastafari faith in the incarnate divinity of Haile Selassie[109] began after news reports of his coronation reached Jamaica,[110] particularly via the two Time magazine articles on the coronation the week before and the week after the event. Haile Selassie's own perspectives permeate the philosophy of the movement.[110][111]

In 1961, the Jamaican government sent a delegation composed of both Rastafarian and non-Rastafarian leaders to Ethiopia to discuss the matter of repatriation, among other issues, with the Emperor. He reportedly told the Rastafarian delegation, which included Mortimer Planno, "Tell the Brethren to be not dismayed, I personally will give my assistance in the matter of repatriation."[112]

When Haile Selassie visited Jamaica on 21 April 1966, somewhere around one hundred thousand Rastafari from all over Jamaica descended on Palisadoes Airport in Kingston,[110] having heard that the man whom they considered to be their Messiah was coming to visit them. Spliffs[113] and chalices[114] were openly[115] smoked, causing "a haze of ganja smoke" to drift through the air.[116][117][118] When Haile Selassie arrived at the airport, he was unable to come down the mobile steps of the airplane, as the crowd rushed the tarmac. He then returned into the plane, disappearing for several more minutes. Finally Jamaican authorities were obliged to request Ras Mortimer Planno, a well-known Rasta leader, to climb the steps, enter the plane, and negotiate the Emperor's descent.[119] When Planno reemerged, he announced to the crowd: "The Emperor has instructed me to tell you to be calm. Step back and let the Emperor land".[120] This day, widely held by scholars to be a major turning point for the movement,[121][122][123] is still commemorated by Rastafarians as Grounation Day, the anniversary of which is celebrated as the second holiest holiday after 2 November, the Emperor's Coronation Day.

From then on, as a result of Planno's actions, the Jamaican authorities were asked to ensure that Rastafarian representatives were present at all state functions attended by His Majesty,[124][125] and Rastafarian elders also ensured that they obtained a private audience with the Emperor,[126] where he reportedly told them that they should not emigrate to Ethiopia until they had first liberated the people of Jamaica. This dictum came to be known as "liberation before repatriation".

Defying expectations of the Jamaican authorities,[127] Haile Selassie never rebuked the Rastafari for their belief in him as the returned Jesus. Instead, he presented the movement's faithful elders with gold medallions – the only recipients of such an honor on this visit.[128][129] During PNP leader (later Jamaican Prime Minister) Michael Manley's visit to Ethiopia in October 1969, the Emperor allegedly still recalled his 1966 reception with amazement, and stated that he felt he had to be respectful of their beliefs.[130] This was the visit when Manley received as a present from the Emperor, the infamous Rod of Correction or Rod of Joshua that is thought to have greatly helped him to win the 1972 election in Jamaica.

Rita Marley, Bob Marley's wife, converted to the Rastafari faith after seeing Haile Selassie on his Jamaican trip. She claimed, in interviews and in her book No Woman, No Cry that she saw a stigmata print on the palm of Haile Selassie's hand (as he waved to the crowd) that resembled the envisioned markings on Christ's hands from being nailed to the cross—a claim that was not supported by other sources, but was used as evidence for her and other Rastafarians to suggest that Haile Selassie I was indeed their messiah.[131] She also converted Bob Marley, who then became internationally recognized, and as a result Rastafari became much better known throughout much of the world.[132] Bob Marley's posthumously released song Iron Lion Zion refers to Haile Selassie.

Haile Selassie's attitude to the Rastafari

Haile Selassie I was the titular head of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and, until his visit to Jamaica in 1966, he had never confirmed nor denied that he was divine,[133] while during his visit he specifically declined to refute the Rastafari belief that he was God.[134][135] After his return to Ethiopia, he dispatched Archbishop Abuna Yesehaq Mandefro to the Caribbean to help draw Rastafarians and other West Indians to the Ethiopian church and, according to some sources, denied his divinity.[136][137][138][139]

In 1948, Haile Selassie donated a piece of land at Shashamane, 250 km south of Addis Ababa, for the use of Blacks from the West Indies. Numerous Rastafari families settled there and there is a community there to this day.[140][141]

Famous quotations

- "A house built on granite and strong foundations, not even the onslaught of pouring rain, gushing torrents and strong winds will be able to pull down. Some people have written the story of my life representing as truth what in fact derives from ignorance, error or envy; but they cannot shake the truth from its place, even if they attempt to make others believe it." — Preface to My Life and Ethiopia's Progress, Autobiography of H.M. Haile Selassie I (English translation).

- "That until the philosophy which holds one race superior and another inferior is finally and permanently discredited and abandoned: That until there are no longer first-class and second class citizens of any nation; That until the color of a man's skin is of no more significance than the color of his eyes; That until the basic human rights are equally guaranteed to all without regard to race; That until that day, the dream of lasting peace and world citizenship and the rule of international morality will remain but a fleeting illusion, to be pursued but never attained and until the ignoble but unhappy regimes that hold our brothers in Angola, in Mozambique, and in South Africa in subhuman bondage have been toppled and destroyed; until bigotry and prejudice and malicious and inhuman self-interest have been replaced by understanding and tolerance and goodwill; until all Africans stand and speak as free human beings, equal in the eyes of the Almighty; until that day, the African continent shall not know peace. We Africans will fight if necessary and we know that we shall win as we are confident in the victory of good over evil" – English translation of 1968 Speech delivered to the United Nations and popularized in a song called War by Bob Marley.

- "Apart from the Kingdom of the Lord there is not on this earth any nation that is superior to any other. Should it happen that a strong Government finds it may with impunity destroy a weak people, then the hour strikes for that weak people to appeal to the League of Nations to give its judgment in all freedom. God and history will remember your judgment." — Address to the League of Nations, 1936.

- "We have finished the job. What shall we do with the tools?" — Telegram to Winston Churchill, 1941.

Honors

|

|

References

- ↑ Gates, Henry Louis and Appiah, Anthony. Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience. 1999, page 902.

- ↑ Erlich, Haggai. The Cross and the River: Ethiopia, Egypt, and the Nile. 2002, page 192.

- ↑ Murrell, Nathaniel Samuel and Spencer, William David and McFarlane, Adrian Anthony. Chanting Down Babylon: The Rastafari Reader. 1998, page 148.

- ↑ Safire, William. Lend Me Your Ears: Great Speeches in History. 1997, page 297-8.

- ↑ Karsh, Efraim. Neutrality and Small States. 1988, page 112.

- ↑ Meredith, Martin. The Fate of Africa: From the Hopes of Freedom to the Heart of Despair. 2005, page 212-3.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Rebellion and Famine in the North under Haile Selassie, Human Rights Watch

- ↑ "Major Religions of the World Ranked by Number of Adherents". Adherents.com.

- ↑ Sullivan, Michael, C. In Search of a Perfect World. 2005, page 86

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Murrell, Nathaniel Samuel and Spencer, William David and McFarlane, Adrian Anthony. Chanting Down Babylon: The Rastafari Reader. 1998, page 172-3.

- ↑ My Life and Ethiopia's Progress. Vol. 2, 1999, page xiii.

- ↑ Murrell, Nathaniel Samuel and Spencer, William David and McFarlane, Adrian Anthony. Chanting Down Babylon: The Rastafari Reader. 1998, page 159.

- ↑ Ghai, Yash P. Autonomy and Ethnicity: Negotiating Competing Claims in Multi-Ethnic States. 2000, page 176.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Mockler, Anthony. Haile Selassie's War. 2003, page 387

- ↑ de Moor, Jaap and Wesseling, H. L. Imperialism and War: Essays on Colonial Wars in Asia and Africa. 1989, page 189.

- ↑ Shinn, David Hamilton and Ofcansky, Thomas P. Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia. 2004, page 265.

- ↑ My Life and Ethiopia's Progress. Vol. 2, 1999, page xii.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Shinn, David Hamilton and Ofcansky, Thomas P. Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia. 2004, page 193-4.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Roberts, Andrew Dunlop. The Cambridge History of Africa. 1986, page 712.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 White, Timothy. Catch a Fire: The Life of Bob Marley. 2006, page 34-5.

- ↑ Untitled Document

- ↑ Rastafari Online Community

- ↑ Lentakis, Michael B. Ethiopia: Land of the Lotus Eaters. 2004, page 41.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Shinn, David Hamilton and Ofcansky, Thomas P. Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia. 2004, page 228.

- ↑ Clarence-Smith, W. G. The Economics of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade in the Nineteenth Century. 1989, page 103.

- ↑ Brody, J. Kenneth. The Avoidable War. 2000, page 209.

- ↑ Gates, Henry Louis and Appiah, Anthony. Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience. 1999, page 698.

- ↑ Rogers, Joel Augustus. The Real Facts about Ethiopia. 1936, page 27.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Mockler, Anthony. Haile Selassie's War. 2003, page 3-4.

- ↑ ETHIOPIAN RULER WINS PLAUDITS OF PARISIANS, The New York Times. 17 May 1924.

- ↑ ETHIOPIAN ROYALTIES DON SHOES IN CAIRO, The New York Times. 5 May 1924.

- ↑ Aspden Rachel. Swinging Addis. New Statesman, 16 August 2007.

- ↑ Nidel, Richard. World Music: The Basics. 2005, page 56.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Roberts, Andrew Dunlop. The Cambridge History of Africa. 1986, page 723.

- ↑ Roberts, Andrew Dunlop. The Cambridge History of Africa. 1986, page 724.

- ↑ Sorenson, John. Ghosts and Shadows: Construction of Identity and Community in an African Diaspora. 2001, page 34.

- ↑ Brockman, Norbert C. An African Biographical Dictionary. 1994, page 381.

- ↑ Henze, Paul B. Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia. 2000, page 205.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Mockler, Anthony. Haile Selassie's War. 2003, page 12.

- ↑ ABYSSINIAN RULER HONORS AMERICANS. The New York Times. 24 October 1930.

- ↑ Emperor is Crowned in Regal Splendor at African Capital. The New York Times. 3 November 1930.

- ↑ ABYSSINIA'S GUESTS RECEIVE COSTLY GIFTS. The New York Times. 12 November 1930.

- ↑ Emperor of Ethiopia Honors Bishop Freeman; Sends Gold-Encased Bible and Cross for Prayer. The New York Times. 27 January 1931.

- ↑ Nahum, Fasil. Constitution for a Nation of Nations: The Ethiopian Prospect. 1997, page 17

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Nahum, Fasil. Constitution for a Nation of Nations: The Ethiopian Prospect. 1997, page 22

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Carlton, Eric. Occupation: The Policies and Practices of Military Conquerors. 1992, page 88-9.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Vandervort, Bruce. Wars of Imperial Conquest in Africa, 1830-1914. 1998, page 158.

- ↑ Churchill, Winston. The Second World War. 1986, page 165.

- ↑ My Life and Ethiopia's Progress: Chapter 35

- ↑ Baudendistel, Rainer. Between Bombs And Good Intentions: The Red Cross And the Italo-Ethiopian War. 2006, page 168.

- ↑ Young, John. Peasant Revolution in Ethiopia. 1997, page 51.

- ↑ Garvey, Marcus. The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers. 1991, page 685.

- ↑ Mockler, Anthony. Haile Selassie's War. 2003, page 123.

- ↑ Spencer, John. Ethiopia at Bay: A Personal Account of the Haile Selassie Years. 2006, page 62.

- ↑ Barker, A. J. The Rape of Ethiopia 1936. page 132

- ↑ Spencer, John. Ethiopia at Bay: A Personal Account of the Haile Selassie Years. 2006, page 72.

- ↑ Moseley, Ray. Mussolini's Shadow: The Double Life of Count Galeazzo Ciano. 1999, page 27.

- ↑ Jarrett-Macauley, Delia. The Life of Una Marson, 1905-65. 1998, page 102-3.

- ↑ Safire, William. Lend Me Your Ears: Great Speeches in History. 1997, page 318.

- ↑ Haile Selassie, "Appeal to the League of Nations," June 1936

- ↑ Time Magazine Man of the Year. 6 January 1936.

- ↑ My Life and Ethiopia's Progress. Vol. 2, 1999, page 11-2.

- ↑ My Life and Ethiopia's Progress. Vol. 2, 1999, page 26-7.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 My Life and Ethiopia's Progress. Vol. 2, 1999, page 25.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Ofcansky, Thomas P. and Berry, Laverle. Ethiopia A Country Study. 2004, page 60-1.

- ↑ My Life and Ethiopia's Progress. Vol. 2, 1999, page 27.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 67.2 My Life and Ethiopia's Progress. Vol. 2, 1999, page 40-2.

- ↑ My Life and Ethiopia's Progress. Vol. 2, 1999, page 170.

- ↑ Shinn, David Hamilton and Ofcansky, Thomas P. Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia. 2004, page 3.

- ↑ Haber, Lutz. The Emperor Haile Selassie I in Bath 1936 - 1940. The Anglo-Ethiopian Society.

- ↑ Barker, A. J. The Rape of Ethiopia 1936. page 156

- ↑ My Life and Ethiopia's Progress. Vol. 2, 1999, page 165.

- ↑ Shinn, David Hamilton and Ofcansky, Thomas P. Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia. 2004, page 201.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Shinn, David Hamilton and Ofcansky, Thomas P. Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia. 2004, page 140-1.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 75.2 75.3 75.4 Ofcansky, Thomas P. and Berry, Laverle. Ethiopia: A Country Study. 2004, page 63-4.

- ↑ Willcox Seidman, Ann. Apartheid, Militarism, and the U.S. Southeast. 1990, page 78.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 77.2 Watson, John H. Among the Copts. 2000, page 56.

- ↑ As described at the Ethiopian Korean War Veterans website.

- ↑ Nathaniel, Ras. 50th Anniversary of His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I. 2004, page 30.

- ↑ Ethiopia Administrative Change and the 1955 Constitution

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 81.2 Mammo, Tirfe. The Paradox of Africa's Poverty. 1999, page 103.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 Bahru Zewde, A History of Modern Ethiopia, second edition (Oxford: James Currey, 2001), pp. 220–26.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 Mammo, Tirfe. The Paradox of Africa's Poverty: The Role of Indigenous Knowledge. 1999, page 100.

- ↑ "General Assembly Resolutions 5th Session". United Nations. Retrieved on 2007-10-16.

- ↑ Semere Haile The Origins and Demise of the Ethiopia-Eritrea Federation Issue: A Journal of Opinion, Vol. 15, 1987 (1987), pp. 9-17

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 De Waal, Alexander. Evil Days: Thirty Years of War and Famine in Ethiopia. 1991, page 58.

- ↑ A BBC report suggests 200,000 deaths, based on a contemporaneous estimate from the Ethiopian Nutrition Institute. While this figure is still repeated in some texts and media sources, it was an estimate that was later found to be "overly pessimistic". See also: De Waal, Alexander. Evil Days: Thirty Years of War and Famine in Ethiopia. 1991, page 58.

- ↑ The Unknown Famine in Ethiopia 1973

- ↑ Jonathan Dimbleby and the hidden famine

- ↑ Eldridge, John Eric Thomas. Getting the Message: News, Truth and Power. 1993, page 26.

- ↑ Dickinson, Daniel. The last of the Ethiopian emperors. BBC. 12 May 2005.

- ↑ De Waal, Alexander. Evil Days: Thirty Years of War and Famine in Ethiopia. 1991, page 61.

- ↑ Woodward, Peter. The Horn of Africa: Politics and International Relations. 2003, page 175.

- ↑ Kumar, Krishna. Postconflict Elections, Democratization, and International Assistance. 1998, page 114.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 95.2 Launhardt, Johannes. Evangelicals in Addis Ababa (1919-1991). 2005, page 239-40.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 Meredith, Martin. The Fate of Africa: From the Hopes of Freedom to the Heart of Despair. 2005, page 216.

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 Shinn, David Hamilton and Ofcansky, Thomas P. Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia. 2004, page 44.

- ↑ "Haile Selassie of Ethiopia Dies at 83", New York Times (28 August 1975). Retrieved on 2007-07-21. "Haile Selassie, the last emperor in the 3,000-year-old Ethiopian monarchy, who ruled for half a century before he was deposed by military coup last September, died yesterday in a small apartment in his former palace. He was 83 years old. His death was played down by the military rulers who succeeded him in Addis Ababa, who announced it in a normally scheduled radio newscast there at 7 a.m. They said that he had been found dead in his bed by a servant, and that the cause of death was probably related to the effects of a prostate operation Haile Selassie underwent two months ago."

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 An Imperial Burial for Haile Selassie, 25 Years After Death. New York Times. 6 November 2000.

- ↑ Marina and David Ottaway, Ethiopia: Empire in Revolution (New York: Africana, 1978), p. 109 n. 22

- ↑ Ethiopians Celebrate a Mass for Exhumed Haile Selassie. New York Times. 1 March 1992.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 Lorch, Donatella. Ethiopia Deals With Legacy of Kings and Colonels. The New York Times. 31 December 1995.

- ↑ Edmonds, Ennis Barrington. Rastafari: From Outcasts to Culture Bearers. 2003, page 55.

- ↑ Granddaughter Esther Selassie's website genealogy

- ↑ Mockler, Anthony. Haile Selassie's War. 2003, page xxvii.

- ↑ Rastafarian beliefs

- ↑ The African Diaspora, Ethiopianism, and Rastafari

- ↑ Haile Selassie King of Kings, Conquering Lion of the tribe of Judah

- ↑ Haile Selassie

- ↑ 110.0 110.1 110.2 Dread, The Rastafarians of Jamaica, by Joseph Owens ISBN 0-435-98650-3

- ↑ The Re-evolution of Rastafari

- ↑ The Rastafarians by Leonard E. Barrett

- ↑ Before the Legend: The Rise of Bob Marley by Christopher John Farley, p. 145

- ↑ People Funny Boy (Lee Perry biography) by David Katz, p. 41.

- ↑ Chanting Down Babylon: The Rastafari Reader by Nathaniel Samuel Murrell, William David Spencer, Adrian Anthony McFarlane, p. 64.

- ↑ Kingston: A Cultural and Literary History, by David Howard p. 176.

- ↑ The State Visit of Emperor Haile Selassie I

- ↑ "Commemorating The Royal Visit by Ijahnya Christian", The Anguillian Newspaper, 22 April 2005.

- ↑ Catch a Fire: The Life of Bob Marley by Timothy White p. 15, 210, 211.

- ↑ Black Heretics, Black Prophets: Radical Political Intellectuals p. 189 by Anthony Bogues

- ↑ This Is Reggae Music: The Story of Jamaica's Music by Lloyd Bradley, p. 192-193.

- ↑ Rastafari: From Outcasts to Culture Bearers by Ennis Barrington Edmonds, p. 86.

- ↑ Verbal Riddim: The Politics and Aesthetics of African-Caribbean Dub Poetry by Christian Habekost, p. 83.

- ↑ Rastafari: From Outcasts to Culture Bearers Page 86 by Ennis Barrington Edmonds

- ↑ Verbal Riddim: The Politics and Aesthetics of African-Caribbean Dub Poetry, page 83 by Christian Habekost

- ↑ Edmonds, p. 86

- ↑ [1] Reggae Routes: The Story of Jamaican Music] By Kevin O'Brien, p. 243.

- ↑ "African Crossroads - Spiritual Kinsmen" Dr. Ikael Tafari, The Daily Nation, Dec. 24 2007

- ↑ White, p. 211.

- ↑ Life Is an Excellent Adventure, Jerry Funk, 2003, p. 149

- ↑ No Woman, No Cry, Rita Marley, p. 43.

- ↑ Bob Marley the Devoted Rastafarian!

- ↑ Must God Remain Greek?: Afro Cultures and God-Talk by Robert E. Hood, p. 93 ISBN 0800624491

- ↑ Reggae Routes: The Story of Jamaican Music By Kevin O'Brien, p. 243. ISBN 1566396298

- ↑ "African Crossroads - Spiritual Kinsmen" The Daily Nation, 24 Dec. 2007

- ↑ "Ethiopians in D.C. Region Mourn Archbishop's Death". Washington Post, 13 January 2006.

- ↑ "Bob Marley Anniversary Spotlights Rasta Religion". National Geographic.

- ↑ "Haile Selassie I - God of the Black race". BBC.

- ↑ Mirror, Mirror: Identity, Race and Protest in Jamaica, Rex Nettleford, William Collins and Sangster Ltd., Jamaica (1970)

- ↑ Jamaican Rastafarian Development Community website

- ↑ The History and Location of the Shashamane Settlement Community Development Foundation, Inc., USA

- ↑ Odluka o proglašenju Njegovog Carskog Veličanstva Cara Etiopije Haila Selasija Prvog za počasnog građanina SFRJ ("Službeni list SFRJ", br. 33/72 319-655

- ↑ Đilas podržao predlog

- ↑ Shoa6

Further reading

- Haile Selassie I. My Life and Ethiopia's Progress: The Autobiography of Emperor Haile Sellassie I. Translated from Amharic by Edward Ullendorff. New York: Frontline Books, 1999. ISBN 0-948390-40-9

- Paul B. Henze. "The Rise of Haile Selassie: Time of Troubles, Regent, Emperor, Exile" and "Ethiopia in the Modern World: Haile Selassie from Triumph to Tragedy" in Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia. New York: Palgrave, 2000. ISBN 0-312-22719-1

- Ryszard Kapuściński, The Emperor: Downfall of an Autocrat. 1978. ISBN 0-679-72203-3

- Dread, The Rastafarians of Jamaica, by Joseph Owens ISBN 0-435-98650-3

- Haile Selassie I : Ethiopia's Lion of Judah, 1979, ISBN 0-88229-342-7

- Haile Selassie's war : the Italian-Ethiopian Campaign, 1935-1941, 1984, ISBN 0-394-54222-3

- Haile Selassie, western education, and political revolution in Ethiopia, 2006, ISBN 978-19-3404320-2

External links

- Ethiopian Treasures - Emperor Haile Selassie I - The Ethiopian Revolution

- Imperial Crown Council of Ethiopia

- Speech to the League of Nations, June 1936 (full text)

- Marcus Garvey's prophecy of Haile Selassie I as the returned messiah

- Haile Selassie I and the Italo-Ethiopian war

- Haile Selassie I, the Later Years

- A critical look at the reign of Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia

- BBC article, memories of his personal servant

- Watch News Reel: His Imperial Majesty, Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia visits Jamaica, 21 April 1966

- Ba Beta Kristiyan Haile Selassie I - The Church of Haile Selassie I

- Haile Selassie I Speaks -Text & Audio-

|

Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia

House of Solomon

Born: 23 July 1892 Died: 27 August 1975 |

||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Zewditu I |

Emperor of Ethiopia 2 November 1930 – 12 September 1974 |

Vacant

Monarchy abolished

|

| Titles in pretence | ||

| Loss of title Communist take-over

|

— TITULAR — Emperor of Ethiopia 12 September 1974 – 27 August 1975 |

Succeeded by Crown Prince Amha Selassie |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||