Education in Germany

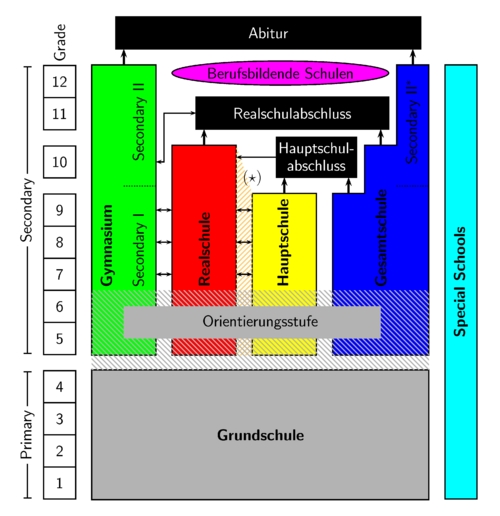

Responsibility for German education system lies primarily with the Bundesländer (states) while the federal government only has a minor role. Optional kindergarten education is provided for all children between three and six years old, after which school attendance is compulsory for twelve years[1]. In Germany, students are graded on a scale of one through six, one being high and six being very low, or failing. Home-schooling is not permitted in any of the German Bundesländer except if a child is suffering from an illness that prevents school attendance. There are also rare cases where foreign families living for a short time in Germany have been granted exemption from compulsory schooling in order to home-school their children in their own language. Primary education usually lasts for four years (6 in Berlin) and public schools are not stratified at this stage.[2] In contrast, secondary education includes four types of schools based on a pupil's ability as determined by teacher recommendations: the Gymnasium includes the most gifted children and prepares students for university studies; the Realschule has a broader range of emphasis for intermediary students; the Hauptschule prepares pupils for vocational education, and the Gesamtschule or comprehensive school combines the three approaches. There are also Förderschulen (schools for the mentally challenged and physically challenged). One in 21 students attends a Förderschule[3] [2] In order to enter a university, high school students are required to take the Abitur examination; however, students possessing a diploma from a vocational school may also apply to enter. A special system of apprenticeship called Duale Ausbildung allows pupils in vocational training to learn in a company as well as in a state-run school.[2] Although Germany has had a history of a strong educational system, recent PISA student assessments demonstrated a weakness in certain subjects. In the test of 43 countries in the year 2000[4], Germany ranked 21st in reading and 20th in both mathematics and the natural sciences, prompting calls for reform.[5]

Overview of the German school system

| Grade | Average ages | School level (Berlin/Brandenburg) |

School level (rest of Germany) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6/7 | elementary | elementary |

| 2 | 7/8 | elementary | elementary |

| 3 | 8/9 | elementary | elementary |

| 4 | 9/10 | elementary | elementary |

| 5 | 10/11 | elementary | secondary |

| 6 | 11/12 | elementary | secondary |

| 7 | 12/13 | secondary | secondary |

| 8 | 13/14 | secondary | secondary |

| 9 | 14/15 | secondary | secondary |

| 10 | 15/16 | secondary | secondary |

| 11 | 16/17 | secondary | secondary |

| 12 | 17/18 | secondary | secondary |

Grundschule (elementary/primary school) can be preceded by voluntary Kindergarten or Vorschulklassen (preparatory classes for elementary school) and lasts four or six years, depending on the state.

Parents who are looking for a suitable school for their child have a considerable choice of elementary schools in Germany today:

- State school. State schools are free of charge. A large majority of German students attend state schools in their neighbourhood. Schools in rich neighbourhoods tend to be better than schools in poor ones. Once children reach school age, many middle-class and working-class class families move away from lower-class areas.

- or, alternatively

- Waldorf School (206 schools in 2007)

- Montessori method school (272)

- Freie Alternativschule (Free Alternative Schools) (65)

- Protestant (63) or Catholic (114) parochial schools

After Grundschule (at 10 years of age, 12 in Berlin and Brandenburg), there are four options for secondary schooling:

- Hauptschule (the least academic, much like a modernized Volksschule [elementary school]) until grade 9 (with Hauptschulabschluss as exit exam),

- Realschule until grade 10 (with Fachoberschulreife(Realschulabschluss) as exit exam),

- Gymnasium (Grammar School) until grade 12 or 13 (with Abitur as exit exam, qualifying for university).

- Gesamtschule (comprehensive school) with all the options of the three "tracks" above.

- After all of those schools the graduates can start a professional career with an apprenticeship in the Berufsschule (vocational school). The Berufsschule is normally attended twice a week during a two, three, or three-and-a-half year apprenticeship; the other days are spent working at a company. This should bring the students knowledge of theory and practice. Please note that the apprenticeship can only be started if a company accepts the apprentice. After this the student will be registered on a list at the Industrie- und Handelskammer IHK (board of trade). During the apprenticeship(s) he is a part-employee of the company and receives a salary from the company. After successful passing of the Berufsschule and the exit exams of the IHK, he/she receives a certificate and is ready for a professional career up to a low management level. In some areas the apprenticeship is teaching skills that are required by law (special positions in a bank, legal assistants).

The grades 5 and 6 form an orientation phase (Orientierunsstufe) in which students, their parents and teachers should decide which of the above mentioned tracks the students should follow. In all states, except Berlin and Brandenburg this orientation phase is embedded into the concerned secondary school types.[6] In Berlin and Brandenburg it is embedded into elementary schools. Teachers give a so called educational (track) recommendation (Bildungs(gang)empfehlung) based on scholar achievements in the main subjects (mathematics, German, Science, foreign language) whose details and legal implications differ from state to state.

In Germany, the 16 states have the exclusive responsibility in the field of education. The federal parliament and the federal government can influence the educational system only by financial aid (to the states). Therefore, there are many different school systems; however, in every state the starting point is Grundschule (elementary school) for a period of four years (six in Berlin and Brandenburg).

All German states have Gymnasium as one possibility for skilled children, and all states - except Baden-Württemberg, Bavaria, Saxony - have Gesamtschule, but in different forms. The eastern states Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia combine Hauptschule and Realschule to Sekundarschule, Mittelschule and Regelschule respectively. All other states distinguish between these schools types.

English is compulsory statewide in secondary schools. In some states, foreign language education starts in Grundschule. For example, in North Rhine-Westphalia, English starts in the 3rd year of school; Brandenburg starts either English or Polish and Baden-Württemberg starts English in the 1st year. Afterwards one can choose either Latin or French and later Spanish. Many schools also offer volunteer study groups for learning other languages.

It is often problematic for families to move from one state to another, because there are extremely different curricula for almost every subject.

Adults who fail to complete their education have the option of attending an Abendgymnasium or Abendrealschule (night school) later in life.

History of German education

The Prussian era (1814 – 1871)

Historically, the Lutheran denomination had a strong influence on German culture, including its education. Martin Luther advocated compulsory schooling and this idea became a model for schools throughout Germany.

During the 18th century, the Kingdom of Prussia was among the first countries in the world (if not the first at all) to introduce free and generally compulsory primary education, consisting of an eight-year course of primary education, Volksschule. It provided not only the skills needed in an early industrialized world (reading, writing, and arithmetics), but also a strict education in ethics, duty, discipline, and obedience. Affluent children often went on to attend preparatory private schools for an additional four years, but the general population had virtually no access to secondary education.

In 1810, after the Napoleonic wars, Prussia introduced state certification requirements for teachers, which significantly raised the standard of teaching. The final examination, Abitur, was introduced in 1788, implemented in all Prussian secondary schools by 1812, and extended to all of Germany in 1871.

German Empire (1871-1918)

When the German Empire was formed in 1871, the school system became more centralized. As learned professions demanded well-educated young people, more secondary schools were established, and the state claimed the sole right to set standards and to supervise the newly established schools.

Four different types of secondary schools developed:

- A nine-year classical Gymnasium (focusing on Latin and Greek or Hebrew, plus one modern language)

- A nine-year Realgymnasium (focusing on Latin, modern languages, science and mathematics)

- A six-year Realschule (without university entrance qualification, but with the option of becoming a trainee in one of the modern industrial, office or technical jobs) and

- A nine-year Oberrealschule (focusing on modern languages, science and mathematics)

By the turn of the 20th century, the four types of schools had achieved equal rank and privilege, although they did not have equal prestige. In 1872, Prussia recognized the first separate secondary schools for girls.

Weimar Republic (1919-1933) to the present

After World War I, the Weimar Republic established a free, universal 4-year elementary school (Grundschule). Most students continued at these schools for another 4-year course and those who were able to pay a small fee went on to an Intermediate school (Mittelschule) that provided a more challenging curriculum for an additional one or two years. Upon passing a rigorous entrance exam after year 4, students could also enter one of the four types of secondary school.

During the Nazi era (1933-1945), indoctrination of Nazi ideologies was added to student education, however, the basic education system remained unchanged. See also: Nazi university.

After World War II, the Allied powers (Soviet Union, France, Britain, and the USA) saw to it that the Nazi ideas were eliminated from the curriculum. They installed educational systems in their respective occupation zones that reflected their own ideas. When West Germany gained partial independence in 1949, its new constitution (Grundgesetz) granted educational autonomy to the state (Länder) governments. This led to a widely varying landscape of school systems, often making it difficult for children to continue schooling whilst moving between states.

More recently, multi-state agreements ensure that basic requirements are universally met by all state school systems. Thus, all children are required to attend one type of school on a full-time basis (i.e. five or six days a week) from the age of 6 to the age of 16. It is possible to change schools if a student shows exceptionally good (or exceptionally poor) abilities. Graduation certificates from one state are recognized by all the other states, and training qualifies teachers for teaching posts in every state.

Education in East Germany

The German Democratic Republic (East Germany) started its own standardized education system in the 1960s. The East German equivalent of both primary and secondary schools was the Polytechnische Oberschule (poly-technical high school), which all students attended for 10 years, from the ages of 6 to 16. At the end of the 10th year, an exit examination was given, and depending upon the results, a student could choose to end their education or choose to undertake an apprenticeship for an additional two years, followed by an Abitur. Students who performed very well and displayed loyalty to the ruling party could change to the Erweiterte Oberschule (extended high school), where they could take their Abitur examinations after 12 school years. This system was abolished in the early 1990s, but continues to influence school life in the eastern German states.

Unequal opportunities

See also: Poverty in Germany

Children from migrant or working class families are less likely to succeed in school than children from middle or upper class backgrounds. This disadvantage for the financially challenged part of the population of Germany is bigger than in any other industrialized nation. [7] However, the true reasons lie beyond monetary reasons. The poor also tend to be less educated. After controlling for parental education money does not play a major role in children's academical outcomes.[8][9]

Immigrant children and youth, most of them of lower-class background, are the fastest-growing segment of the German population, so their prospects bear heavily on the well-being of the country. 30% of Germans aged 15 years and younger have at least one parent born abroad. In the big cities 60% of children aged 5 years and younger have at least one parent born abroad.[10]. Immigrant children academically underperform their peers[11] Again however, immigrants tend to be less educated than Germans. After controlling for parental education ethnic group does not play a role in children's academic outcomes.[12]

Immigrants from China and Vietnam are doing exceptionally well. In eastern Germany Vietnamese and Chinese of lower-class background outperform students from European backgrounds (despite the fact that in most cases their parents are poorer and less educated than the parents of their European-born peers). Teachers in Eastern Germany also have been shown to be more motivated than teachers in Western Germany. That might be another reason for Asian achievement.[13]

Male gender is associated with low educational attainment in Germany. 63% percent of students attending special education programs for the academically challenged are male, only 37% are female. Boys are less likely to meet the state-wide performance targets. They are more likely to drop out school. They are more likely to be classified emotionally disturbed. 86% of the students receiving special training because of emotional disturbance are male.[14] Research shows a class-effect: Middle class boys are doing as well as middle class girls in terms of educational achievement but lower class boys are lagging behind lower class girls. Lack of male role models contributes to lower-class boys' low academic achievement.[15]

Helping kids at risk

Children, whose families receive welfare, children whose parents dropped out of school, children of teenage parents, children raised by a lone parent, children raised in crime-ridden inner-city neighbourhoods, children who have multiple young siblings and children who live in overcrowded substandard apartments are at risk of poor educational achievement in Germany. Often this things go together making it very hard for children to overcome the odds. A number of measures have been discussed to help those children reach their full potential.[16]

Kindergarten

Kindergarten has been shown to improve school readiness in children at risk. Children attending a Kindergarten were less likely to have impaired speech or impaired motor development. Only 50% of children, whose parents did not graduate from school, are ready for school at age six. However if these children were enrolled in a high-quality three year Kindergarten programme 87% were ready for school. Thus Kindergarten helps to overcome unequal opportunities.[17]

Home-visits to Families in need

Families whose children are at risk for low academic achievement may be visited by trained professionals. They offer a wide variety of services that depend on each child's and each family's background and their needs. Such professionals may visit pregnant low income women and talk with them positive health-related behaviors such as following a healthy diet or refraining from the use of alcohol or tobacco while pregnant. Positive health related behavior may have a major impact on children's school performance. They may provide information on childcare and social services, help parents in crisis and model problem solving skills. They may help implement the preschool/school curriculum at home or provide an own a curriculum of educational games designed to improve language, development and cognitive skills. In most cases this is voluntary. Families who are eligible for the program can decide for themselves whether or not they want to participate and if they do not want to continue to participate there are no penalties.[18]

Is the German school system biased against working class students?

In Germany most children are streamed by ability into different schools after fourth grade. However some visit comprehensive schools that do not stream by ability. The Progress in International Reading Literacy Study revealed that working class children needed better reading abilities than middle class children to be nominated for the Gymnasium. After controlling for reading abilities odds to be nominated for Gymnasium for upper middle class children were 2.63 times better than the ones for working class children.

| Points needed to be nominated for Gymnasium |

||

|---|---|---|

| ... teachers nominating child for Gymnasium | ... parents wanting child to attend Gymnasium | |

| children from upper-middle class backgrounds | 537 | 498 |

| children from lower-middle class backgrounds | 569 | 559 |

| children of parents holding pink collar jobs | 582 | 578 |

| children of self-employed parents | 580 | 556 |

| children from upper working class backgrounds | 592 | 583 |

| children from lower working class backgrounds | 614 | 606 |

| http://www.iglu.ifs-dortmund.de/assets/files/iglu/IGLU2006_Pressekonferenz.doc retrieved May 27th 2008 | ||

Life in a German school

Although German students are not very different from other students across the world, there are organizational differences. The main points are outlined below; however, it should be noted that there are additional differences across the 16 states of Germany.

- Each group of students born in the same year forms one grade or class, which remains the same for elementary school (years 1 to 4), orientation school (if there's orientation school in the state) or orientation phase (at Gymnasium years 5 to 6), and secondary school (years 5 to 10 in "Realschulen" and "Hauptschulen"; years 5 to 11 (differences between states) in "Gymnasien"). Changes are possible, though, when there is a choice of subjects, e.g. additional languages, and the class is split.

- Most subjects (except PE, art, sciences, music and the subjects which are taught in courses, like French) are taught in the students' own classroom (similar to a "home room"); the pupils stay in their room whilst the teachers move from class to class. This is common throughout school up to year 11 (5 in Saxony, 7 in Brandenburg).

- Sometimes there is also a "Sanitätsdienst" (medical service), where pupils voluntarily perform first aid.

- Students sit at tables, not desks (usually two pupils at one table), sometimes arranged in a semi-circle or another geometric or functional shape. During exams in classrooms, the tables are sometimes arranged in columns with one pupil per table (if permitted by the room's capacities) in order to prevent cheating; at many schools, this is only the case for some exams in the two final years of school, i.e. some of the exams counting for the final grade on the high school diploma.

- There normally is no school uniform or dress code other than the most basic rules of decency. Many private schools have a very simple dress code consisting of, for example, "no shorts, no sandals, no clothes with holes". Some schools are trying out school uniforms, but those aren't as formal as seen in for example the UK. They mostly consist of a normal pullover/shirt and jeans of a certain color, sometimes with the school's symbol on it.

- Sometimes students can buy school T-shirts which they can wear voluntarily.

- School usually starts between 7.30 a.m. and 8:15 a.m. and can finish as early as 12; instruction at lower classes almost always ends before lunch. In higher grades, however, afternoon lessons are very common and periods may have longer gaps without teacher supervision between them. Ordinarily, afternoon classes are not offered every day and/or continuously until early evening, leaving students with large parts of their afternoons free of school; some schools (Ganztagsschulen), however, offer classes or mainly supervised activities throughout the afternoons in order to offer supervision of the students rather than an increase in teaching. Afternoon lessons can go up to 6 o'clock.

- Depending on the school, there are breaks of 5 to 10 minutes after each period. There is no lunch break as school usually finishes before 1:30 for junior school. However, at schools that have "Nachmittagsunterricht" (= afternoon classes) ending after 1:30 there's sometimes a lunch break of 45 to 90 minutes, though many schools lack any special break in general. Some schools that have regular breaks of 5 minutes between periods have additional 15 or 20 minute breaks after the second and fourth period.

- In German state schools periods are exactly 45 minutes. Each subject is usually taught for two to three periods every week (main subjects like Mathematics, German or foreign languages are taught for four to six periods) and usually no more than two periods consecutively. The beginning of every period and, usually, break is generally announced with an audible signal such as a bell.

- Exams (which are always supervised) are usually essay based, rather than multiple choice. As of 11th grade exams usually consist of no more than three separate exercises. While most exams in the first grades of secondary schools usually span no more than 90 minutes, exams in 11th to 13th grade may span four periods or more (without breaks).

- At every school type, students study one foreign language (in most cases English) for at least five years. The study is, however, far more rigorous in Gymnasium. Students leaving Hauptschule rarely attain fluency. In Gymnasium, students can choose from a wider range of languages (mostly English, French, Russian (mostly in east german Bundesländer) or Latin) as the first language in 5th grade, and a second mandatory language in 6th or 7th grade. Students are required to study English either as a first or second foreign language (with the exception of Saarland, which requires French for historic and geographical reasons). Some types of Gymnasium also require an additional third language (such as Spanish, Italian, Russian, Latin or Ancient Greek) or an alternative subject (usually based on one or two other subjects, e.g. English politics (English & politics), dietetics (biology) or media studies (arts & German) in 9th or 11th grade. Gymnasiums ordinarily offer further subjects starting at 11th grade, with some schools offering a fourth foreign language.

- A small number of schools have a Raucherecke (smokers' corner), a small area of the schoolyard where students over the age of eighteen are permitted to smoke in their breaks. Those special areas were banned in the states of Berlin, Hessen and Hamburg, Brandenburg at the beginning of the 2005-06 school year. (Bavaria, Schleswig-Holstein, Lower Saxony 2006-07)). From now on schools in these states forbid smoking for pupils and teachers and offences at school will be punished. Some other states in Germany are planning to introduce similar laws.

- As state schools are public, smoking is universally prohibited inside the buildings. Smoking teachers are generally asked not to smoke while at or near school.

- Students over 14 years are permitted to leave the school compound during breaks at some schools. Teachers or school personnel tend to prevent younger pupils from leaving early and strangers from entering the compound without permission.

- Tidying up the classroom and schoolyard is often the task of the pupils. Unless a group of pupils volunteers, individuals are picked sequentially.

- Many schools have AGs or Arbeitsgemeinschaften (clubs) for afternoon activities such as sports, music or acting, but participation is not necessarily common. Some schools also have special mediators, who are student volunteers trained to resolve conflicts between their classmates or younger pupils.

- Only few schools have actual sports teams that compete with other schools'. Even if the school has a sports team, most students are not very aware of it.

- While student newspapers used to be very common until the late 20th century, many of them are now very short-lived, usually vanishing when the team graduates. Student newspapers are often financed mostly by advertisements.

- Usually schools don't have their own radio stations or TV channels. Larger universities often have a local student-run radio station, however.

- Although most German schools and state universities do not have classrooms equipped with a computer for every student, schools usually have at least one or two computer rooms and most universities offer a limited number of rooms with computers on every desk. State school computers are usually maintained by the same exclusive contractor in the entire city and updated slowly. Internet access is often provided by phone companies free of charge. Especially in schools the teachers' computer skills are often very low.

- At the end of their schooling, students usually undergo a cumulative written and oral examination (Abitur in Gymnasiums or Abschlussprüfung in Realschulen and Hauptschulen). Students leaving Gymnasium after 9th grade do have the leaving examination of the Hauptschule and after 10th grade do have the Mittlere Reife (leaving examination of the Realschule).

- After 10th grade Gymnasium students may quit school for at least one year of job education if they do not wish to continue. Realschule and Hauptschule students who have passed their Abschlussprüfung may decide to continue schooling at a Gymnasium, but are sometimes required to take additional courses in order to catch up.

- Corporal punishment was banned in West Germany in 1973 and at least officially in East Germany in 1949.

- Fourth grade (or sixth, depending on the state) is often quite stressful for students of lower performance and their families. Many feel tremendous pressure when trying to achieve placement in Gymnasium, or at least when attempting to avoid placement in Hauptschule. Germany is unique compared to other western countries in its early segregation of students based on academic achievement.

The grade scale ranges from 1 to 6, where 1 is "sehr gut" or "Excellent" (corresponding to an A+ in America) and 6 is "ungenügend" or "Failed" (literally "insufficient"). After 11th grade, in the "Kollegstufe" ("Oberstufe" in some eastern states, e.g. Saxony), the scale is replaced by a point system with a maximum of 15 points (exceptional achievement) corresponding to grade 1+, 4 points or less (grade 4- or less) counting as a deficite as of 12th grade and jeopardising the admission to the Abitur exams.

The school year

The school year starts after the summer break (different from state to state, usually end/mid of August) and is divided into two semesters. There are typically 12 weeks of holidays, in addition to public holidays. Exact dates differ between states, but there are generally 6 weeks of summer and two weeks of Christmas holiday. The other holiday periods are given in spring (usually around Easter Sunday) and autumn (the former "harvest holiday", where farmers used to need their children for field work). Schools can also schedule two or three special days off per semester.

Report cards (Zeugnis) are issued twice a year at the end of the semester, usually in February and June or July. Students who do not measure up to minimum standards (usually no 6, no more than one 5 unless there are other subjects with 3 or better) have to repeat a year (which happens to almost 5% of students every year). If pupils have to repeat a year, it is colloquially called sitzenbleiben (literally remain seated). Once they have reached 12th grade, students may usually not fail more than twice in succession or they will not be admitted to the Abitur exams at the end of 13th grade.

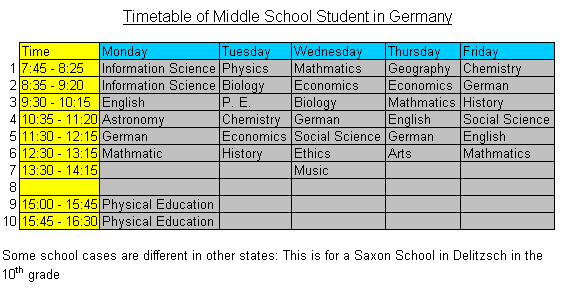

Model timetables

Students have about 30-40 periods of 45 minutes each per week, but especially secondary schools today switch to 90 minutes lessons (Block) which count as two 'traditional' lessons. To manage classes that are taught three lessons per week there is still one 45 minute lesson each day, mostly between the first two blocks. There are about 12 compulsory subjects: two or three foreign languages (one to be taken for 9 years, another for at least 3 years), physics, biology, chemistry and usually civics/social studies (for at least 5, 7, 3, and 2 years, respectively), and mathematics, music, art, history, German, geography, PE and religious education/ethics for 9 years. A few afternoon activities are offered at German schools - mainly choir or orchestra, sometimes sports, drama or languages. Many of these are offered as semi-scholastic AG's (Arbeitsgemeinschaften - literally "working groups"), which are mentioned, but not officially graded in students' report cards. Other common extracurricular activities are organized as private clubs, which are very popular in Germany.

| Time | Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 07.30-08.15 am | English | Physics | Biology | Physics | French(course) |

| 08.20-09.05 am | History | English | Chemistry | Maths | Chemistry |

| 09.05-09.25 am | break | ||||

| 09.25-10.10 am | Latin (course) | French (course) | Maths | Latin (course) | Maths |

| 10.15-11.00 am | German | French (course) | Religion (course) | Latin (course) | German |

| 11.00-11.15 am | break | ||||

| 11.15-12.00 pm | Music | Mathematics | Sport | German | Biology |

| 12.05-12.50 pm | Religion (course) | History | Sport | English | Latin (course) |

This timetable reflects a school week at a normal 9-year Gymnasium in North Rhine-Westphalia (which should change to 8 years by 2013). There are three blocks of lessons where every "hour" takes 45 minutes. After each block, there is a break of 15-20 minutes, also after the 6th hour (the number of lessons changes from year to year, so it's possible that one would be in school until four o'clock). "Nebenfächer" (= minor fields of study) are taught two times a week, "Hauptfächer" (=major subjects) are taught three times. (Latin is taught four times a week because it is the newly-started third language.)

Typical grade 10 timetable at a middle school in 2003

Typical grade 10 timetable at a middle school in 2003

In grades 11-13, 11-12, or 12-13 (depending on the school system), each student majors in two or three subjects ("Leistungskurse", "Grundkurse"/"Profilkurse"). These are usually taught five hours per week. The other subjects are usually taught three periods per week.

| Time | Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 08.00-08.45 am | Spanish | Chemistry | Psychology | |||

| 08.50-09.35 am | Spanish | Biology | Chemistry | Psychology | ||

| 09.50-10.35 am | Arts | Mathematics | Spanish | Mathematics | Chemistry | |

| 10.40-11.25 am | Arts | Mathematics | Spanish | Mathematics | Chemistry | |

| 11.35-12.20 pm | Geography/Social Studies+ | German | History | English | Biology | |

| 12.25-1.10 pm | Geography/Social Studies+ | German | History | English | Choir | |

| 1.10-1.55 pm | ||||||

| 2.00-2.45 pm | English | Religion | ||||

| 2.50-3.35 pm | English | Religion | ||||

| 3.50-4.35 pm | German | |||||

| 4.40-5.25 pm | Physical Education | German | ||||

| 5.30-6.15 pm | Physical Education |

+Geography in the first part of the year, Social Studies in the second

Example of Baden-Württemberg

| Time | Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 08.00-08.45 am | English | Religion | French | Physics | German | |

| 08.50-09.35 am | English | Religion | French | Physics | German | |

| 09.55-10.40 am | German | Geography/Social Studies (taught in English) | Mathematics | Geography/Social Studies (taught in English) | Mathematics | |

| 10.45-11.30 am | German | Geography/Social Studies (taught in English) | Mathematics | Geography/Social Studies (taught in English) | Mathematics | |

| 11.50-12.35 pm | Physics | Politics-Economy | History | English | French | |

| 12.40-1.25 pm | Physics | Politics-Economy | History | English | French | |

| 1.40-2.25 pm | Arts | "Seminarfach"+ | History | PE (different sports offered as courses) | ||

| 2.30-3.15 pm | Arts | "Seminarfach"+ | History | PE (different sports offered as courses) |

+"Seminarfach" is a compulsory class in which each student is prepared to turn in his/her own research paper at the end of the semester. The class is supposed to train the students' scientific research skills that will be necessary in their later university life.

There are many differences in the 16 states of Germany and there are alternatives to this basic pattern, e.g. Waldorfschulen or other private schools. Adults can also go back to evening school and take the Abitur exam.

Organizational aspects

In Germany, education is the responsibility of the states (Länder) and part of their constitutional sovereignty (Kulturhoheit der Länder). Teachers are hired by the Ministry of Education for the state and usually are employed for life after a certain period (verbeamtet) (which, however, is not comparable in timeframe nor competitiveness to the typical tenure track, e.g. at universities in the US). This praxis depends on the state and is currently changing. A parents' council is elected to voice the parents' views to the school's administration. Each class elects one or two "Klassensprecher" (class presidents, if two are elected usually one is male and the other female), the class presidents meet several times a year as the "Schülerrat" (students' council). A team of school presidents is also elected by the students each year, the school presidents' main purpose is organizing school parties, sports tournaments and the like for their fellow students. The local town is responsible for the school building and employs the janitorial and secretarial staff. For an average school of about 600 – 800 students, there may be two janitors and one secretary. School administration is the responsibility of the teachers (who will receive a reduction in their teaching obligations if they participate).

Recent developments

After much public debate about Germany's international ranking (PISA - Programme for International Student Assessment), some things are beginning to change. There has been a trend towards a less ideological discussion on how to develop schools. These are some of the new trends:

- Establishing federal standards on quality of teaching

- More practical orientation in teacher training

- Transfer of some responsibility from the Kultusministerium (Ministry of Education) to local school

Since the 1990s, a few changes have already been taking place in many schools:

- Introduction of bilingual education in some subjects

- Experimentation with different styles of teaching

- Equipping all schools with computers and Internet access

- Creation of local school philosophy and teaching goals ("Schulprogramm"), to be evaluated regularly

- Reduction of Gymnasium school years (Abitur after grade 12) and introduction of afternoon periods as in many other western countries

Gesamtschulen vs. streaming

There has been a public debate about streaming students by ability. Opponents of streaming by ability claim that streaming is unfair and have pointed out that countries that did very well on PISA, such as Finland, do not stream by ability. Proponents of streaming have pointed out that German comprehensive schools ranked below other German schools on PISA and that students from the lower socio-economic groups attending comprehensive schools fare worse on PISA than middle-class students attending the same schools.

College and university

- See also: Academic degree

- See also: List of universities in Germany

Since the end of World War II, the number of youths entering universities has more than tripled, but university attendance still lags behind many other European nations. This is partly because of the dual education system, with its strong emphasis on apprenticeships (see also German model).

Universities in Germany are part of the free state education system, which means that there are very few private universities and colleges. While the organizational structure claims to go back to the university reforms by Wilhelm von Humboldt in the early 19th century, it has also been criticized by some (including the German-born, former Stanford University president Gerhard Casper) for having an unbalanced focus, more on education and less on research, and the lack of independence from state intervention. Many of today's German public universities, in fact, bear less resemblance to the original Humboldt vision than, for example, a typical US institution.

German university students largely choose their own programme of study and professors choose their own subjects for research and teaching. This elective system often results in students spending many years at university before graduating, and is currently under review. There are no fixed classes of students who study together and graduate together. Students change universities according to their interests and the strengths of each university. Sometimes students attend two, three or more different universities in the course of their studies. This mobility means that at German universities there is a freedom and individuality unknown in the USA, the UK, or France.

Upon leaving school, students may choose to go on to university; however, most (male) students will have to serve nine months of military or alternative service (Zivildienst) beforehand.

The Gymnasium graduation (Abitur) opens the way to any university; there are no entrance examinations. (Another way to gain access to an university is via a Berufsoberschule The Abiturdurchschnittsnote (similar to GPA in the US, or A-Level results in the UK) is the deciding factor in granting university places; an institution may quote an entry requirement for a particular course. This is called numerus clausus (literally "restricted number"), but it generally only applies to popular courses with very limited places; for example a medical course could require an Abiturgrade of between 1.0 to 1.5.

While at Gymnasium a student cannot take courses that result in university credits. This might also have to do with the fact that the credit system is unknown in Germany so far, although it is being introduced with the Bologna process that is intended to unify education and degrees for all EU states. What counts at the end of one's studies is a bundle of certificates ("Scheine") issued by the professors proving that the required courses (and/or exams) were successfully taken. With a few exceptions students may not receive certificates for courses they attend before officially matriculating at the university (i.e. while at Gymnasium), although their attendance may sometimes be counted as such. Usually there are few required specific courses, rather students choose from a more or less broad range of classes in their field of interest, while this varies greatly upon the choice of subject. Once a student has acquired the needed number of such certificates and can (if he or she is a Magister student) verify his or her regular attendance at a minimum number of optional courses, he or she can decide to register for the final examinations. In many cases, the grades of those certificates are completely discarded and the final diploma grade consists only of the grades of the final exams and master thesis. This can potentially impair the student's motivation to achieve excellence during their studies, although most students try to aim for higher scores in order to comply with requirements for BAFöG or scholarships, or, simply, for vanity.

At Gymnasium, students are under strict observation by teachers, and their attendance at all courses is checked regularly. At German universities, however, class attendance is only checked for courses in which the student requires a certificate, and attendance checks are usually a lot more liberal (usually a signature or sign is considered proof of attendance, even if the signing is not supervised) and sporadic, although repeated failure to attend a course without a proper excuse (i.e. sick note) usually results in the loss of the chance to get a certificate. Life at German universities may seem anonymous and highly individual at first, but most students find a group of fellow students with common interests in their first year, and then often take courses together and study in this group up to the final exam studies.

While there are curricula for the first two or three years in the sciences, in the liberal arts, every student picks the lectures and seminars he or she prefers (usually admission to the Zwischenprüfung requires three certificates, which may each be earned in one of several different seminars), and takes the exams at the end of the study period. Each student decides for him- or herself when he or she feels ready for the final exam. Some take the minimum 4 years, most take 5-6 years, some may even spend 10 years at university (often because they changed subjects several times). After 13 years at school plus maybe 1 year in the military, graduates may sometimes be almost 30 years old when they apply for their first real job in life, although most will have had a number of part-time jobs or temporary employments between semesters.

If they have successfully studied at university for two years (after a Zwischenprüfung/Vordiplom), students can transfer to other countries for graduate studies. Usually they finish studies after 4-6 years with a degree called the Diplom (in the sciences) or Magister (in the arts), which is equivalent to a M.Sc. or M.A., or a Magister Artium.

A special kind of degree is the Staatsexamen. It is a government licensing examination that future doctors, teachers, lawyers, judges, public prosecutors and pharmacists have to pass to be allowed to work in their profession. Students usually study at university for 4-8 years before they take the first Staatsexamen. Afterwards teachers and jurists go on to work in their future jobs for two years, before they are able to take the second Staatsexamen, which tests their practical abilities in their jobs. The first Staatsexamen is equivalent to a M.Sc., M.A, LL.M. or J.D.

However, there is another type of post-Abitur university training available in Germany: the Fachhochschulen (Universities of Applied Science), which offer similar degrees as classic universities, but often concentrate on applied science (as the English name suggests). While in classic universities it is an important part to study WHY a method is scientifically right that point is not so important to students at Universities of Applied Science. There it is stressed to study what systems and methods exist, where they come from, their pros and cons, how to use them in practice and last but not least when are they to use and when not. Students start their courses together and graduate (more or less) together and there is little choice in their schedule (but this must no be at several studies). To get on-the-job experience, internship semesters are a mandatory part of studying at a Fachhochschule. Therefore the students at U-o-A-S are better trained in transferring learned knowledge and skills into practise while students of classic Universities are better trained in method developing. But as professors at U-o-A-S have done their doctorate at classic universities and classic universities have regarded the importance of practice both types are coming closer and closer. It is nowadays more a differentiation between practice orientation and theoretical orientation of science.

After about 4-5 years (depending on how a student arranges the courses he or she takes over the course of his studies, and on whether he or she has to repeat courses) a Fachhochschule student has a complete education and can go right into working life. Fachhochschule graduates received traditionally a title that starts with "Dipl." (Diploma) and ends with "(FH)", e.g. "Dipl. Ing. (FH)" for a graduate engineer from a Fachhochschule. The FH Diploma is roughly equivalent to a Bachelor degree. An FH Diploma does not usually qualify the holder for a Ph.D. program directly -- many universities require an additional entrance exam or participation in theoretical classes from FH candidates. The last point is based on the history. When FHs or U-o-A-S were set up the professors were mainly teachers from higher schools but did not hold a doctorate. This has completely changed since the end of the eighties, but professors of classic universities still regard themselves as "the real professors", which indeed is no longer true. Due to the Bologna process the bachelor and master degrees are introduced to classic universities and universities of applied sciences in the same way.

All courses at the roughly 250 classic universities and universities of applied sciences used to be free - like any school in Germany. One might also say the government offered a full scholarship to everyone. However, students that took longer than the Regelstudienzeit ("regular length of studies", a statistically calculated average that is the minimum amount of time necessary to successfully graduate) did have to pay Langzeitstudiengebühren ("long-time study fees") of about 500 EUR per semester, in a number of states. Today there are a few private institutions (especially business schools) that charge tuition fees, but they don't have high recognition and high standards as public universities have. Another negative impact of the private institution in Germany is that they usually have only one or few subjects so that they can't get high recognition in international competition.

One does have to pay for one's room and board plus one's books. After a certain age, one must obtain obligatory student health insurance (50 EUR per month), and one always has to pay for some other social services for students (40-100 EUR per semester). Students often enjoy very cheap public transport (Semesterticket) in and around the university town. There are cheap rooms for students built by the Studentenwerk, an independent non-profit organization partially funded by the state. These may cost 150 EUR per month, without any food. Otherwise an apartment can cost 500 EUR, but often students share apartments, with 3 or 5 people per apartment. Food is about 100 EUR (figures for 2002). Many banks provide free accounts to students up to a certain age (usually around 25).

The German Constitutional Court recently ruled that a federal law prohibiting tuition fees is unconstitutional, on the grounds that education is the sole responsibility of the states. Following this ruling, several state governments (e.g. in Bavaria and North Rhine-Westfalia) proclaimed their intention to introduce tuition of around €500 per semester within the next year. Many state legislatures have passed laws that allow, but do not officially force, universities to demand tuition up to a limit, usually €500. In preparation to comply with several local laws aiming to give universities more liberty in their decisions but requiring them to be more economical (effectively privatising them), many universities hastily decided to introduce the fees, usually without any exceptions other than a bare minimum. As a direct result, student demonstrations in the scale of 100 to 10000 participants are frequent in the affected cities, most notably Frankfurt in Hesse, where the state officially considered introducing universal tuition fees in the €1500 range.

There are no university-sponsored scholarships in Germany, but a number of private and public institutions hand out scholarships, usually to cover the cost of living and books. Moreover, there is a law (BAFöG or Bundesausbildungsförderungsgesetz) that sees to it that needy people can get up to 550 EUR per month for 4-5 years if they or their parents cannot afford all the costs involved with studying. Part (typically half) of this money is given as an interest-free loan and has to be paid back. Many universities planning to introduce tuition fees have announced their intention to use a part of the money to create scholarship programmes, although the exact details are mostly vague.

Most students will move to the university town if it is far away. Getting across Germany from Flensburg to Konstanz takes a full day (1000 km or 620 miles). But, as mentioned above, there is no university-provided student housing on campus in Germany, since most campuses are scattered all over the city for historical reasons. Traditionally, university students rented a private room in town, which was their home away from home. This is no longer the standard, but one still finds this situation. One third to one half of the students works to make a little extra money, often resulting in a longer stay at university.

Figures for Germany are roughly:

- 1,000,000 new students at all schools put together for one year

- 400,000 Abitur graduations

- 30,000 doctoral dissertations per year

- 1000 habilitations per year (qualification to become a professor)

Degrees: Most courses lead up to a diploma called Diplom or Magister and these are equivalent to the Masters degree in other countries (after a minimum of 4 to 5 years). The doctoral degree usually takes another 3-5 years, with no formal classes, but independent research under the tutelage of a single professor. Most doctoral candidates work as teaching- or research assistants, and are paid a reasonably competitive salary.

Recently, changes related to the so-called Bologna-Agreement have started taking place to install a more internationally acknowledged system, which includes new course structures - the (hitherto unknown) Bachelor degree and the Master degree - and ETCS credits. These changes have not been forced on the universities and the hope has been that they will develop them from the bottom up. So far, students have been reluctant to start these new courses because they know that within Germany, employers are not used to them and prefer the well-known system. In the winter semester of 2001, only 5% of all students aspired to complete either a bachelor or master degree, but this has changed as many universities and universities of applied sciences change their course offerings to exclusively provide only bachelor or master degree certificates (e.g. Bremen or Erfurt).

In addition, there are the courses leading to Staatsexamen (state examinations), e. g. for lawyers and teachers, that qualify for entry into German civil service, but which are not recognized elsewhere as an academic degree (although the courses are sometimes identical).

On the whole though, Germany universities are internationally recognized. This is demonstrated by their positioning in international university rankings. Ten German universities were listed in the top 200 universities in the world in the 2006 THES - QS World University Rankings.[19]

References

- ↑ The first nine years are students have to attend the school during all weekdays. The remaining three years they only have to attend some days, depending on the next educational “track″they are following.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 COUNTRY PROFILE: GERMANY U.S. Library of Congress. December 2005. Retrieved 2006, 12-04

- ↑ Schülerzahlen Statistisches Bundesamt Deutschland. Retrieved 2007, 07-20

- ↑ OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA): Participating countries

- ↑ Experts: Germany Needs to Step up School Reforms Deutsche Welle. April 12, 2006. Retrieved 2006, 12-04

- ↑ A decision has then already been taken, but during this phase it is easier to revert it. In fact, this is seldom the case for teachers being afraid of sending students to more academic schools and parents being afraid of sending their children to less academic schools.

- ↑ Internationale Leistungsvergleiche im Schulbereich Bildungsministerium für Bildung und Forschung. Retrieved 2007, 07-20

- ↑ Lauterbach, Wolfgang (2003): Armut in Deutschland - Folgen für Familien und Kinder. Oldenburg: Oldenburger Universitätsreden. ISBN 3-8142-1143-X, S. 32-33

- ↑ Becker/Nietfeld (1999): Arbeitslosigkeit und Bildungschancen von Kindern im Transformationsprozess. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, Jg. 51, Heft 1, 1999

- ↑ BiBB: Menschen mit Migrationshintergrund - neue Definition, alte Probleme

- ↑ Hans Boeckler Stiftung: OECD-Studie: Mangel an Akademikern

- ↑ Isoplan: Neue Erkenntnisse aus der PISA-Studie

- ↑ TAZ: Ostlehrer integrieren Migrantenkinder besser

- ↑ Renate Rastätter, MdL: Nicht dümmer, aber die Dummen

- ↑ Renate Rastätter, MdL: Nicht dümmer, aber die Dummen

- ↑ Hans Weiß (Hrsg.): Frühförderung mit Kindern und Familien in Armutslagen. München/Basel: Ernst Reinhardt Verlag. ISBN 3-497-01539-3

- ↑ Die Zeit (14. Mai 2008): Kindergarten gleicht soziale Unterschiede aus. [1]

- ↑ Hans Weiß (Hrsg.): Frühförderung mit Kindern und Familien in Armutslagen. München/Basel: Ernst Reinhardt Verlag. ISBN 3-497-01539-3

- ↑ QS World University Rankings, THES - QS

See also

- Education in East Germany

- List of schools in Germany

- List of universities in Germany.

External links

- List of schools in Germany

- List of courses of study in Germany

- German Academic Exchange Service

- The German education system: basic facts

- German Federal Law on Support in Education - BAföG

- German education financing by BAföG

- Free union of student bodies (FZS) of Germany

- Germany Announces Short List for Elite Universities

- Application-Standards for students and pupils in Germany

- The New Student's Reference Work/German Universities {1914}

|

|||||||||||