Griffin

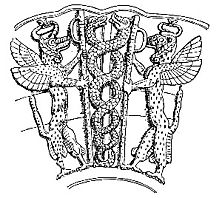

The griffin is a legendary creature with the body of a lion and the head and often wings of an eagle. As the lion was traditionally considered the king of the beasts and the eagle the king of the birds, the griffin was thought to be an especially powerful and majestic creature. Griffins are normally known for guarding treasure.[1] In antiquity it was a symbol of divine power and a guardian of the divine.[2]

Most contemporary illustrations give the griffin forelegs like an eagle's legs with talons, although in some older illustrations it has a lion's forelimbs; it generally has a lion's hindquarters. Its eagle's head is conventionally given prominent ears; these are sometimes described as the lion's ears, but are often elongated (more like a horse's), and are sometimes feathered.

Infrequently, a griffin is portrayed without wings (or a wingless eagle-headed lion is identified as a griffin); in 15th-century and later heraldry such a beast may be called an alce or a keythong. In heraldry, a griffin always has forelegs like an eagle's hind legs; the beast with forelimbs like a lion's forelegs was distinguished by perhaps only one English herald of later heraldry as the opinicus; the word "opinicus" escaped the editors of the Oxford English Dictionary. The modern generalist calls it the lion-griffin, as for example, Robin Lane Fox, in Alexander the Great, 1973:31 and notes p. 506, who remarks a lion-griffin attacking a stag in a pebble mosaic at Pella, perhaps as an emblem of the kingdom of Macedon or a personal one of Alexander's successor Antipater.

After "griffin", the spelling gryphon is the most common variant in English, gaining popularity following the publication of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland as can be observed from usage in The Times and elsewhere. Less common variants include gryphen, griffen, and gryphin.; from Latin grȳphus, from Greek γρύψ gryps, from γρύπος grypos hooked. The spelling "griffon" (from Middle English and Middle French) was previously frequent but is now rare, probably to avoid confusion with the breed of dog called a griffon.

Contents |

Medieval lore

A 9th-century Irish writer by the name of Griffin Neal asserted that griffins were strictly monogamous. Not only did they mate for life, but if one partner died, the other would continue throughout the rest of its life alone, never to search for a new mate. The griffin was thus made an emblem of the Church's views on remarriage.

Being a union of a terrestrial beast and an aerial bird, it was seen in Christianity to be a symbol of Jesus Christ, who was both human and divine. As such it can be found sculpted on churches.[1]

According to Stephen Friar, a griffin's claw was believed to have medicinal properties and one of its feathers could restore sight to the blind.[1] Goblets fashioned from griffin claws (actually antelope horns) and griffin eggs (actually ostrich eggs) were highly prized in medieval European courts.[3]

Since its emergence as a major seafaring power in the Middle Ages and Renaissance griffins have been depicted as part of the Republic of Genoa's coat of arms, rearing at the sides of the shield bearing the Cross of St. George.

By the 12th century the appearance of the griffin was substantially fixed: "All its bodily members are like a lion's, but its wings and mask are like an eagle's."[4] It is not yet clear if its forelimbs are those of an eagle or of a lion. Although the description implies the latter, the accompanying illustration is ambiguous. It was left to the heralds to clarify that.

In architecture

In architectural decoration the griffin is usually represented as a four-footed beast with wings and the head of a leopard or tiger with horns, or with the head and beak of an eagle.

The griffin is the symbol of the Philadelphia Museum of Art and you can see bronze castings of them perched on each corner of the museum's roof, protecting its collection.[5][6]

In literature

- For fictional characters named Griffin, see Griffin (surname)

- John Milton, in Book II of Paradise Lost, refers to the legend of the griffin in describing Satan:

| “ | As when a Gryfon through the Wilderness With winged course ore Hill or moarie Dale, |

” |

- Griffins are used widely in Persian poetry. Rumi is one such poet who writes in reference to griffins (for example, in The Essential Rumi, translated from Persian by Coleman Barks, p 257).

- In Dante Alighieri's The Divine Comedy, a griffin pulls the chariot which brings Beatrice to Dante in Canto XXIX of the Purgatory.

- In Voltaire's La Princesse de Babylone (The Princess of Babylon; 1768), two griffins transport princess Formosante.

- Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865), the Queen of Hearts orders the Gryphon to take Alice to see the Mock Turtle and hear its story.

- In L. Frank Baum's The Marvelous Land of Oz (1904) the evil witch Old Mombi transforms herself into a griffin to escape from the good witch Glenda.

- Although no Gryphons are referenced in C. S. Lewis's The Chronicles of Narnia, the movie, "The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe" portrays a griffin, Gryphon.

- In T. H. White's The Once and Future King (1958), young Arthur and his stepbrother Kay battle a fierce griffin with aid from Robin Wood A.K.A. Robin Hood soon after freeing captives of Morgan le Fay.

- In Geoff Ryman's The Warrior Who Carried Life (1980), a huge, white griffin know as "The Beast Who Talks to God" is one of the major characters.

- In the Dragonlance series (1984 onwards), griffins are under the command of Silvanesti Elves.

- In Neil Gaiman's Sandman comic book series (1988-1996), a griffin is one of three guardians of Morpheus's palace in The Dreaming.

- In Mercedes Lackey and Larry Dixon's The Mage Wars Trilogy - The Black Gryphon (1994), The White Gryphon (1995) and The Silver Gryphon (1996) - gryphons known as Skandranon, and, later, his son Tadrith are among the lead characters. In this series gryphons have human level intelligence and can use magic.

- Griffins are among the magical creatures in J. K. Rowling's Harry Potter series (1997-2007). Harry Potter's house at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry is called Gryffindor after its founder Godric Gryffindor. Fans have speculated that "Gryffindor" may come from the French gryffon d'or (golden griffin), but, oddly, its emblem is not a griffin, but a lion - which represents the supposed courageous nature of a true Gryffindor. In the movie versions, the gargoyle guarding the headmaster's office is depicted as a half-phoenix, half-lion griffin and the door-knocker is a griffin.

- In Tamora Pierce's Squire, part of the Protector of the Small quartet, the main character Kel stumbles upon a baby griffin kidnapped from his parents and is forced to care for him until they can be found.

- In Patricia McKillip's Song for the Basilisk (1998), a griffin is one of the book's main characters and appears as a symbol of the ruling house.

- In Bruce Coville's Song of the Wanderer (1999), the second book of The Unicorn Chronicles series, a gryphon named Medafil is a character.

- In Wilanne Schneider Belden's Frankie! (1987), a human baby turns into a griffin.

- In Collinsfort Village by Joe Ekaitis (2005), a gentlemanly griffin resides on a mountain overlooking an imaginary Colorado suburb.

- In Bill Peet's The Pinkish Purplish Bluish Egg (1984) a dove finds an odd egg, and raises the griffin that hatches from it. The griffin has the head of a bald eagle rather than the more usual golden eagle.

- In Katherine Robert's "The Amazon Temple Quest" a gryphon is connected with the Amazons and it is the one to give them power and to give them the ability to reproduce without men.

(unknown dates)

- In Nick O'Donohoe's Crossroads series (including The Magic and the Healing, Under the Healing Sign, and Healing of Crossroads) about veterinary students called upon to help mythological creatures, griffins play a significant role.

- In James C. Christianson's Voyage of the Basset, a griffon saves Casandra from the trolls.

- In The Spiderwick Chronicles, Simon Grace, Jared Grace's twin brother, befriends a wounded Griffin and names it Byron.

In natural history

Some large species of Old World vultures are called gryphons, including the griffon vulture (Gyps fulvus), as are some breeds of dog (griffons).

The scientific species name for the Andean Condor is Vultur gryphus; Latin for "griffin-vulture".

The name of an oviraptoran dinosaur Hagryphus giganteus is Latin for "gigantic Ha's Griffin".

As a first name and surname

In the mid-1990s, "Griffin" steadily became more popular as a baby name for boys in the U.S. In 1990, it was ranked 629th. In 2006, it was ranked 254th. Also rising in popularity is the various other spellings of the name such as Griffen or Gryphon.

"Griffin" occurs as a surname in English-speaking countries. It has its origins as an anglicised form of the Irish "Ó Gríobhtha", "O' Griffin", and "Ó Griffey".

Welsh people who were anglicised, changed the name to "Griffith" and similar names. This shift is reinforced where the family has taken canting arms charged with a griffin.

"Griffin" (and variants in other languages) may also have been adopted as a surname by other families who used arms charged with a griffin or a griffin's head (just as the House of Plantagenet took its name from the badge of a sprig of broom or planta genista). This is ostensibly the origin of the Swedish surname "Grip" (see main article).

The name Homa (Persian for griffin) is a well-known firstname for girls in Iran. A story about Homa who has lost one of her milkteeth is featured in Iranian textbooks for third graders.

Other

- Westminster College in Salt Lake City, Utah holds the mascot of the Griffin

- University of Guelph in Guelph, Ontario holds the mascot of the Gryphon

- Canisius College in Buffalo, New York holds the mascot of the Griffin [1]

- Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia holds the mascot of the Griffin [2]

- Reed College in Portland, Oregon holds the mascot of the Griffin.

- The now-defunct Kennedy High School in Willingboro, New Jersey held the mascot of the Gryphon.

- Rocky Mount High School in Rocky Mount, North Carolina holds the mascot of the Gryphon.

Notes and references

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Friar, Stephen (1987). A New Dictionary of Heraldry. London: Alphabooks/A & C Black. p. 173. ISBN 0906670446.

- ↑ von Volborth, Carl-Alexander (1981). Heraldry: Customs, Rules and Styles. Poole: New Orchard Editions. pp. 44–45. ISBN 185079037X.

- ↑ Bedingfeld, Henry; Gwynn-Jones, Peter (1993). Heraldry. Wigston: Magna Books. pp. 80–81. ISBN 1854224336.

- ↑ White, T. H. (1992 (1954)). The Book of Beasts: Being a Translation From a Latin Bestiary of the Twelfth Century. Stroud: Alan Sutton. pp. 22–24. ISBN 075090206X.

- ↑ Philadelphia Museum of Art - Giving : Giving to the Museum : Specialty License Plates

- ↑ Philadelphia Museum of Art :: Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States :: Glass Steel and Stone

See also

- Eyrie, a griffin-like Neopet

- Gallery of flags with animals#Griffin

- Griffin (surname)

- Griffon (Dungeons & Dragons)

- Hippogriff

- Homa

- JAS 39 Gripen, a fighter aircraft built by Saab

- SAAB Automobile Badge/Logo built by SAAB/General Motors Saab Automobile

- Simurgh

- Sphinx

External links

- The Gryphon Pages, a repository of griffin lore and information

- The Medieval Bestiary: Griffin

- Dave's Mythical Creatures and Places: Griffin

Further reading

- Bisi, Anna Maria, Il grifone: Storia di un motivo iconografico nell'antico Oriente mediterraneo (Rome:Università) 1965.

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||