Pope Gregory I

| Pope Saint Gregory the great | |

|

|

| Papacy began | September 3, 590 |

|---|---|

| Papacy ended | 12 March, 604 |

| Predecessor | Pelagius II |

| Successor | Sabinian |

| Consecration | September 3, 590 |

| Birth name | Gregorius |

| Born | c. 540 Rome, Italy |

| Died | March 12, 604 Rome, Italy |

| Buried | Cappella Clementina, St. Peter's Basilica, since 1606 |

| Nationality | Roman |

| Denomination | Catholic |

| Residence | Rome |

| Parents | Gordianus, Saint Silvia |

| Other popes named Gregory | |

Pope Saint Gregory I or Gregory the Great (c. 540 – 12 March 604) was pope from 3 September 590 until his death.

He is also known as Gregory the Dialogist in Eastern Orthodoxy because of his Dialogues. For this reason, English translations of Orthodox texts will sometimes list him as "Gregory Dialogus". He was the first of the popes to come from a monastic background. Gregory is a Doctor of the Church and one of the six Latin Fathers.

Immediately after his death, Gregory was canonized by popular acclaim.[1] He is seen as a patron of England[2] for having sent Augustine of Canterbury there on mission.

Contents |

Biography

Early life

The exact date of St. Gregory's birth is uncertain, but is usually estimated to be around the year 540,[3] in the city of Rome. His parents named him Gregorius, which according to Aelfric in "An Homily on the Birth-Day of S. Gregory," translated by Elizabeth Elstob, "... is a Greek Name, which signifies in the Latin Tongue Vigilantius, that is in English, Watchful...."[4] The medieval writers who give this universally believed etymology[5] do not hesitate to apply it to the life of Gregory. Aelfric, for example, goes on: "He was very diligent in God's Commandments."[6]

When Gregory was a child Italy was retaken from the Goths by Justinian I, emperor of the Roman Empire ruling from Constantinople. The war was over by 552. An invasion of the Franks was defeated in 554. The western empire had long since vanished in favor of the Gothic kings of Italy. The senate had been disbanded. After 554 there was peace in Italy and the appearance of restoration, except that the government now resided in Constantinople. Italy was still united into one country, "Rome" and still shared a common official language, the very last of classical Latin.

As the fighting had been mainly in the north, the young Gregorius probably saw little of it. Totila sacked and vacated Rome in 547, destroying most of its ancient population, but in 549 he invited those who were still alive to return to the empty and ruinous streets. It has been hypothesized that young Gregory and his parents, Gordianus and Silvia, retired during that intermission to Gordianus' Sicilian estates, to return in 549.[7]

Gregory had been born into a wealthy noble Roman family with close connections to the church. The Lives in Latin use nobilis but they do not specify from what historical layer the term derives or identify the family. No connection to patrician families of the Roman Republic has been demonstrated.[8] Gregory's great-great-grandfather had been Pope Felix III,[9] but that pope was the nominee of the Gothic king, Theodoric.[8]

The family owned and resided in a villa suburbana on the Caelian Hill, fronting the same street, now the Via di San Gregorio, as the former palaces of the Roman emperors on the Palatine Hill opposite. The north of the street runs into the Colosseum; the south, the Circus Maximus. In Gregory's day the ancient buildings were in ruins and were privately owned.[10] Villas covered the area. Gregory's family also owned working estates in Sicily[11] and around Rome.[12]

Gregory's father, Gordianus, held the position of Regionarius in the Roman Church. Nothing further is known about the position. Gregory's mother, Silvia, was well-born and had a married sister, Pateria, in Sicily. Gregory later had portraits done in fresco in their former home on the Caelian and these were described 300 years later by John the Deacon. Gordianus was tall with a long face and light eyes. He wore a beard. Silvia was tall, had a round face, blue eyes and a cheerful look. They had another son, name and fate unknown.[13]

The monks of St. Andrew's (the ancestral home on the Caelian) had a portrait of Gregory made after his death, which John the Deacon also saw in the 9th century. He reports the picture of a man who was "rather bald" and had a "tawny" beard like his father's and a face that was intermediate in shape between his mother's and father's. The hair that he had on the sides was long and carefully curled. His nose was "thin and straight" and "slightly aquiline." "His forehead was high." He had thick, "subdivided" lips and a chin "of a comely prominence" and "beautiful hands."[14]

Gregory was educated. Gregory of Tours reports that "in grammar, dialectic and rhetoric ... he was second to none...."[15] He wrote correct Latin but did not read or write Greek. He knew Latin authors, natural science, history, mathematics and music and had such a "fluency with imperial law" that he may have trained in law, it has been suggested, "as a preparation for a career in public life."[15]

While his father lived, Gregory took part in Roman political life and at one point was Prefect of the City.

Gregory as monastic

Gregory's father's three sisters were nuns. Gregory's mother Silvia herself is a saint. On his father's death, he converted his family villa suburbana, located on the Caelian Hill just opposite the Circus Maximus, into a monastery dedicated to the apostle Saint Andrew. Gregory himself entered as a monk. After his death it was rededicated as San Gregorio Magno al Celio.

Eventually, Pope Pelagius II ordained him a deacon and solicited his help in trying to heal the schism of the Three Chapters in northern Italy. In 579, Pelagius II chose Gregory as his apocrisiarius or ambassador to the imperial court in Constantinople. On his return to Rome, Gregory served as secretary to Pelagius II, and was elected Pope to succeed him.

Gregory as Pope

| Papal styles of Pope Gregory I |

|

|

[[Image:{{{image}}}|60px|]] |

|

| Reference style | His Holiness |

| Spoken style | Your Holiness |

| Religious style | Holy Father |

| Posthumous style | Saint, Great |

When he became Pope in 590, among his first acts were writing a series of letters disavowing any ambition to the throne of Peter and praising the contemplative life of the monks. At that time the Holy See had not exerted effective leadership in the West since the pontificate of Gelasius I. The episcopacy in Gaul was drawn from the great territorial families, and identified with them: the parochial horizon of Gregory's contemporary, Gregory of Tours, may be considered typical; in Visigothic Spain the bishops had little contact with Rome; in Italy the papacy was beset by the violent Lombard dukes and the rivalry of the Jews in the Exarchate of Ravenna and in the south. The scholarship and culture of Celtic Christianity had developed utterly unconnected with Rome, and it was from Ireland that Britain and Germany were likely to become Christianized, or so it seemed.

Gregory is credited with re-energizing the Church's missionary work among the barbarian peoples of northern Europe. He is most famous for sending a mission under Augustine of Canterbury to evangelize the pagan Anglo-Saxons of England. The mission was successful, and it was from England that missionaries later set out for the Netherlands and Germany.

Servus servorum Dei

In line with his predecessors such as Dionysius, Damasus, and St. Leo the Great, St. Gregory asserted the primacy of the office of the Bishop of Rome. Although he did not employ the term "Pope", he summed up the responsibilities of the papacy in his official appellation, as "servant of the servants of God". As Benedict of Nursia had justified the absolute authority of the abbot over the souls in his charge, so Gregory expressed the hieratic principle that he was responsible directly to God for his ministry.

St. Gregory's pontificate saw the development of the notion of private penance as parallel to the institution of public penance. He explicitly taught a doctrine of Purgatory where a soul destined to undergo purification after death because of certain sins, could begin its purification in this earthly life, through good works, obedience and Christian conduct, making the travails to come lighter and shorter.

St. Gregory's relations with the Emperor in the East were a cautious diplomatic stand-off. He concentrated his energies in the West, where many of his letters are concerned with the management of papal estates. His relations with the Merovingian kings, encapsulated in his deferential correspondence with Childebert II, laid the foundations for the papal alliance with the Franks that would transform the Germanic kingship into an agency for the Christianization of the heart of Europe — consequences that remained in the future.

More immediately, Gregory undertook the conversion of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, where inaction might have encouraged the Celtic missionaries already active in the north of Britain. Sending Augustine of Canterbury to convert the Kingdom of Kent was prepared by the marriage of the king to a Merovingian princess who had brought her chaplains with her. By the time of Gregory's death, the conversion of the king and the Kentish nobles and the establishment of a Christian toehold at Canterbury were established.

St. Gregory's chief acts as Pope include his long letter issued in the matter of the schism of the Three Chapters of the bishops of Venetia and Istria. He is also known in the East as a tireless worker for communication and understanding between East and West. He is also credited with increasing the power of the papacy.

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, he was declared a saint immediately after his death by "popular acclamation".

Works

Liturgical reforms

In letters, St. Gregory remarks that he moved the Pater Noster (Our Father) to immediately after the Roman Canon and immediately before the Fraction. This position is still maintained today in the Roman Liturgy. The pre-Gregorian position is evident in the Ambrosian Rite. Gregory added material to the Hanc Igitur of the Roman Canon and established the nine Kyries (a vestigial remnant of the litany which was originally at that place) at the beginning of Mass. He also reduced the role of deacons in the Roman Liturgy.

Sacramentaries directly influenced by Gregorian reforms are referred to as Sacrementaria Gregoriana. With the appearance of these sacramentaries, the Western liturgy begins to show a characteristic that distinguishes it from Eastern liturgical traditions. In contrast to the mostly invariable Eastern liturgical texts, Roman and other Western liturgies since this era have a number of prayers that change to reflect the feast or liturgical season; These variations are visible in the collects and prefaces as well as in the Roman Canon itself.

A system of writing down reminders of chant melodies was probably devised by monks around 800 to aid in unifying the church service throughout the Frankish empire. Charlemagne brought cantors from the Papal chapel in Rome to instruct his clerics in the “authentic” liturgy. A program of propaganda spread the idea that the chant used in Rome came directly from Gregory the Great, who had died two centuries earlier and was universally venerated. Pictures were made to depict the dove of the Holy Spirit perched on Gregory's shoulder, singing God's authentic form of chant into his ear. This gave rise to calling the music "Gregorian chant". A more accurate term is plainsong or plainchant.

Sometimes the establishment of the Gregorian Calendar is erroneously attributed to Gregory the Great; however, that calendar was actually instituted by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582 by way of a papal bull entitled, Inter gravissimas.

In the Eastern Orthodox Church, Gregory is credited with compiling the Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts. This liturgy is celebrated on Wednesdays, Fridays, and certain other weekdays during Great Lent in the Eastern Orthodox Church and those Eastern Catholic Churches which follow the Byzantine Rite.

Writings

Gregory is the only Pope between the fifth and the eleventh centuries whose correspondence and writings have survived enough to form a comprehensive corpus. Some of his writings are:

- Sermons (forty on the Gospels are recognized as authentic, twenty-two on Ezekiel, two on the Song of Songs)

- Dialogues, a collection of often fanciful narratives including a popular life of Saint Benedict

- Commentary on Job, frequently known even in English-language histories by its Latin title, Magna Moralia

- The Rule for Pastors, in which he contrasted the role of bishops as pastors of their flock with their position as nobles of the church: the definitive statement of the nature of the episcopal office

- Copies of some 854 letters have survived, out of an unknown original number recorded in Gregory's time in a register. It is known to have existed in the Vatican, its last known location, in the 9th century. It consisted of 14 papyrus rolls, now missing. Copies of letters had begun to be made, the largest batch of 686 by order of Adrian I. The majority of the copies, dating from the 10th to the 15th century, are stored in the Vatican Library.[16]

Opinions of the writings of Gregory vary. "His character strikes us as an ambiguous and enigmatic one," Cantor observed. "On the one hand he was an able and determined administrator, a skilled and clever diplomat, a leader of the greatest sophistication and vision; but on the other hand, he appears in his writings as a superstitious and credulous monk, hostile to learning, crudely limited as a theologian, and excessively devoted to saints, miracles, and relics". [17][18]

Issues

Controversy with Eutychius

In Constantinople, Gregory took issue with the aged Patriarch Eutychius of Constantinople, who had recently published a treatise, now lost, on the General Resurrection. Eutychius maintained that the resurrected body "will be more subtle than air, and no longer palpable".[19] Gregory opposed with the palpability of the risen Christ in Luke 24:39. As the dispute could not be settled, the Roman emperor, Tiberius II Constantine, undertook to arbitrate. He decided in favor of palpability and ordered Eutychius' book to be burned. Shortly after both Gregory and Eutychius became ill, Gregory recovered, but Eutychius died on April 5, 582, at age 70. On his deathbed he recanted inpalpability and Gregory dropped the matter. Tiberius also died a few months after Eutychius.

Sermon on Mary Magdalene

In a sermon whose text is given in Patrologia Latina,[20] Gregory stated that he believed "that the woman Luke called a sinner and John called Mary was the Mary out of whom Mark declared that seven demons were cast" (Hanc vero quam Lucas peccatricem mulierem, Joannes Mariam nominat, illam esse Mariam credimus de qua Marcus septem damonia ejecta fuisse testatur), thus identifying the sinner of Luke 7:37, the Mary of John 11:2 and 12:3 (the sister of Lazarus and Martha of Bethany), and Mary Magdalene, from whom Jesus had cast out seven demons, related in Mark 16:9.

While most Western writers shared this view, it was not seen as a Church teaching, but as an opinion, the pros and cons of which were discussed.[21] With the liturgical changes made in 1969, there is no longer mention of Mary Magdalene as a sinner in Roman Catholic liturgical materials.[22]

The Eastern Orthodox Church has never accepted Gregory's identification of Mary Magdalene with the sinful woman.

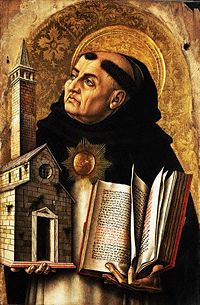

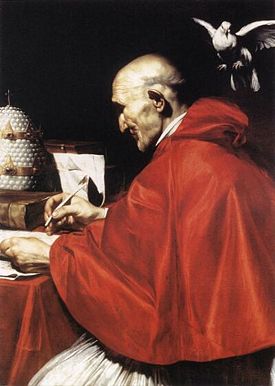

Iconography

In art Gregory is usually shown in full pontifical robes with the tiara and double cross, despite his actual habit of dress. Earlier depictions are more likely to show a monastic tonsure and plainer dress. Orthodox icons traditionally show St. Gregory vested as a bishop, holding a Gospel Book and blessing with his right hand. It is recorded that he permitted his depiction with a square halo, then used for the living. [23] A dove is his attribute, from the well-known story recorded by his friend Peter the Deacon,[24] who tells that when the pope was dictating his homilies on Ezechiel a curtain was drawn between his secretary and himself. As, however, the pope remained silent for long periods at a time, the servant made a hole in the curtain and, looking through, beheld a dove seated upon Gregory's head with its beak between his lips. When the dove withdrew its beak the pope spoke and the secretary took down his words; but when he became silent the servant again applied his eye to the hole and saw the dove had replaced its beak between his lips.[25]

This scene is shown as a version of the traditional Evangelist portrait (where the Evangelists' symbols are also sometimes shown dictating) from the tenth century onwards. An early example is the dedication miniature from the an eleventh century manuscript of St. Gregory's Moralia in Job.[26] The miniature shows the scribe, Bebo of Seeon Abbey, presenting the manuscript to the Holy Roman Emperor, Henry II. In the upper left the author is seen writing the text under divine inspiration Usually the dove is shown whispering in Gregory's ear for a clearer composition.

The imaginative and anachronistic example at the top of this article is from the studio of Carlo Saraceni or by a close follower, ca 1610. From the Giustiniani collection, the painting is conserved in the Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Rome.[27] The face of Gregory is a caricature of the features described by John the Deacon mentioned under his early life above: total baldness, outthrust chin, beak-like nose, where John had described partial baldness, a mildly protruding chin, slightly aquiline nose and strikingly good looks. In this picture also Gregory has his monastic back on the world, which the real Gregory, despite his reclusive intent, was seldom allowed to have.

Alms

Alms in Christianity is defined by passages of the New Testament such as Matthew 19:21, which commands "...go and sell that thou hast, and give to the poor ... and come and follow me." A donation on the other hand is a gift to some sort of enterprise, profit or non-profit.

On the one hand the the alms of St. Gregory are to be distinguished from his donations, but on the other he probably saw no such distinction. The church had no interest in secular profit and as pope Gregory did his utmost to encourage that high standard among church personnel. Apart from maintaining its facilities and supporting its personnel the church gave most of the donations it received as alms.

Gregory is known for his administrative system of charitable relief of the poor at Rome. They were predominantly refugees from the incursions of the Lombards. The philosophy under which he devised this system is that the wealth belonged to the poor and the church was only its steward. He received lavish donations from the wealthy families of Rome, who, following his own example, were eager to expiate to God for their sins. He gave alms equally as lavishly both individually and en masse. He wrote in letters:[28]

- "I have frequently charged you ... to act as my representative ... to relieve the poor in their distress ...."

- "... I hold the office of steward to the property of the poor ...."

The church received donations of many different kinds of property: consumables such as food and clothing; investment property: real estate and works of art; and capital goods, or revenue-generating property, such as the Sicilian latifundia, or agricultural estates, staffed and operated by slaves, donated by Gregory and his family. The church already had a system for circulating the consumables to the poor: associated with each parish was a diaconium or office of the deacon. He was given a building from which the poor could at any time apply for assistance.[29][30]

The state in which Gregory became pope in 590 was a ruined one. The Lombards held the better part of Italy. Their predations had brought the economy to a standstill. They camped nearly at the gates of Rome. The city was packed with refugees from all walks of life, who lived in the streets and had few of the necessities of life. The seat of government was far from Rome in Constantinople, which appeared unable to undertake the relief of Italy. The pope had sent emissaries, including Gregory, asking for assistance, to no avail.

In 590 Gregory could wait for Constantinople no longer. He organized the resources of the church into an administration for general relief. In doing so he evidenced a talent for and intuitive understanding of the principles of accounting, which was not to be invented for centuries. The church already had basic accounting documents: every expense was recorded in journals called regesta, "lists" of amounts, recipients and circumstances. Revenue was recorded in polyptici, "books." Many of these polyptici were ledgers recording the operating expenses of the church and the assets, the patrimonia. A central papal administration, the notarii, under a chief, the primicerius notariorum, kept the ledgers and issued brevia patrimonii, or lists of property for which each rector was responsible.[31]

Gregory began by aggressively requiring his churchmen to seek out and relieve needy persons and reprimanded them if they did not. In a letter to a subordinate in Sicily he wrote: "I asked you most of all to take care of the poor. And if you knew of people in poverty, you should have pointed them out ... I desire that you give the woman, Pateria, forty soldi for the childrens' shoes and forty bushels of grain ...."[32] Soon he was replacing administrators who would not cooperate with those who would and at the same time adding more in a build-up to a great plan that he had in mind. He understood that expenses must be matched by income. To pay for his increased expenses he liquidated the investment property and paid the expenses in cash according to a budget recorded in the polyptici. The churchmen were paid four times a year and also personally given a golden coin for their trouble.[33]

Money, however, was no substitute for food in a city that was on the brink of famine. Even the wealthy were going hungry in their villas. The church now owned between 1300 and 1800 square miles of revenue-generating farmland divided into large sections called patrimonia. It produced goods of all kinds, which were sold, but Gregory intervened and had the goods shipped to Rome for distribution in the diaconia. He gave orders to step up production, set quotas and put an administrative structure in place to carry it out. At the bottom was the rusticus who produced the goods. Some rustici were or owned slaves. He turned over part of his produce to a conductor from whom he leased the land. The latter reported to an actionarius, the latter to a defensor and the latter to a rector. Grain, wine, cheese, meat, fish and oil began to arrive at Rome in large quantities, where it was given away for nothing as alms.[34]

Distributions to qualified persons were monthly. However, a certain proportion of the population lived in the streets or were too ill or infirm to pick up their monthly food supply. To them Gregory sent out a small army of charitable persons, mainly monks, every morning with prepared food. It is said that he would not dine until the indigent were fed. When he did dine he shared the family table, which he had saved (and which still exists), with 12 indigent guests. To the needy living in wealthy homes he sent meals he had cooked with his own hands as gifts to spare them the indignity of receiving charity. Hearing of the death of an indigent in a back room he was depressed for days, entertaining for a time the conceit that he had failed in his duty and was a murderer.[33]

These and other good deeds and charitable frame of mind completely won the hearts and minds of the Roman people. They now looked to the papacy for government, ignoring the rump state at Constantinople, which had only disrespect for Gregory, calling him a fool for his pacifist dealings with the Lombards. The office of urban prefect went without candidates. From the time of Gregory the Great to the rise of Italian nationalism the papacy was most influential in ruling Italy.

Famous quotes and anecdotes

- Non Angli, sed Angeli - "They are not Angles, but Angels". Aphorism of unknown origin summarizing words reported to have been spoken by Gregory when he first encountered blue-eyed, blond-haired English boys at a slave market, sparking his dispatching of St. Augustine of Canterbury to England to convert the English, according to Bede.[35] He said: "Well named, for they have angelic faces and ought to be co-heirs with the angels in heaven."[36] Discovering that their province was Deira, he went on to add that they would be rescued de ira, "from the wrath", and that their king was named Aella, Alleluia, he said.[37]

- Ecce locusta - "Look at the locust." Gregory himself wanted to go to England as a missionary and started out for there. On the fourth day as they stopped for lunch a locust landed on the edge of the Bible Gregory was reading. He exclaimed ecce locusta, "look at the locust", but reflecting on it he saw it as a sign from Heaven since the similar sounding loco sta means "stay in place." Within the hour an emissary of the pope[38] arrived to recall him.[36]

- Pro cuius amore in eius eloquio nec mihi parco - "For the love of whom (God) I do not spare myself from his Word."[39] The sense is that since the creator of the human race and redeemer of him unworthy gave him the power of the tongue so that he could witness, what kind of a witness would he be if he did not use it but preferred to speak infirmly?

- Non enim pro locis res, sed pro bonis rebus loca amanda sunt - "Things are not to be loved for the sake of a place, but places are to be loved for the sake of their good things." When Augustine asked whether to use Roman or Gallican customs in the mass in England, Gregory said, in paraphrase, that it was not the place that imparted goodness but good things that graced the place, and it was more important to be pleasing to the Almighty. They should pick out what was "pia", "religiosa" and "recta" from any church whatever and set that down before the English minds as practice.[40]

Memorials

Lives

In Britain, appreciation for Gregory remained strong even after his death, with him being called Gregorius noster ("our Gregory") by the British.[41] It was in Britain, at a monastery in Whitby, that the first full length life of Gregory was written, in c.713.[42] Appreciation of Gregory in Rome and Italy itself, however, did not come until later. The first vita of Gregory written in Italy was not produced until John the Deacon in the 9th century.

Monuments

The namesake church of San Gregorio al Celio (largely rebuilt from the original edifices during the 17th-18th centuries) remembers his work. One of the three oratories annexed, the oratory of St. Silvia, is said to lie over the tomb of Gregory's mother.

Feast Day

The current Roman Catholic calendar of saints, revised in 1969 as instructed by the Second Vatican Council,[43] celebrates St. Gregory the Great on 3 September. Before that, the General Roman Calendar assigned his feast day to 12 March, the day of his death in 604. This day always falls within Lent, during which there are no obligatory Memorials. For this reason his feast day was moved to 3 September the day of his episcopal consecration in 590.[44]

The Eastern Orthodox Church and the associated Eastern Catholic Churches continue to commemorate St. Gregory on 12 March. The occurrence of this date during Great Lent is considered appropriate in the Byzantine Rite, which traditionally associates Saint Gregory with the Divine Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts, celebrated only during that liturgical season.

Other Churches too honour Saint Gregory: the Church of England on 3 September, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and the Episcopal Church in the United States on 12 March.

A traditional procession is held in Żejtun, Malta in honour of Saint Gregory (San Girgor) on Easter Wednesday, which most often falls in April, the range of possible dates being 25 March to 28 April.

References

- ↑ "Gregory I". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. (2005). Ed. F.L. Cross. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ "Gregory the Great". Catholic Culture. Retrieved on 2007-12-05.

- ↑ Gregory mentions in Dialogue 3.2 that he was alive when Totila attempted to murder Carbonius, Bishop of Populonia, probably in 546. In a letter of 598 (Register, Book 9, Letter 1) he rebukes Bishop Januarius of Cagliari, Sardinia, excusing himself for not not observing 1 Timothy 5.1, which cautions against rebuking elders. 5.9 defines elderly women to be 60 and over, which may apply to everyone. Gregory appears not to consider himself an elder, limiting his birth to no earlier than 539, but 540 is the typical selection. Dudden (1905), page 3, notes 1-3.

- ↑ Aelfric; Elizabeth Elstob (translator); William Elstob (1709). An English-Saxon Homily on the Birth-day of St. Gregory: Anciently Used in the English-Saxon Church, Giving an Account of the Conversion of the English from Paganism to Christianity. London: W. Bowyer. pp. 4.

- ↑ Elizabeth goes on to state that "Paulus Diaconus, who first writ the life of St. Gregory, and is followed by all the after Writers on that subject, observes that 'ex Greco eloquio in nostra lingua ... vigilator, seu vigilans sonat." However, Paul the deacon is too late for the first vita, or life.

- ↑ The name is Biblical, derived from New Testament contexts: grēgorein is a present, continuous aspect, meaning to be watchful of forsaking Christ. It is derived from a more ancient perfect, egrēgora, "roused from sleep", of egeirein, "to awaken someone." Thayer, Joseph Henry (1962). Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament being Grimm's Wilke's Clavis Novi Testamenti Translated Revised and Enlarged. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan Publishing House.

- ↑ Dudden (1905), pages 36-37.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Dudden (1905), page 4.

- ↑ Whether III or IV depends on whether Pope Felix II is to be considered pope.

- ↑ Dudden (1905), pages 11-15.

- ↑ Dudden (1905), pages 106-107.

- ↑ Richards (1980), page 25.

- ↑ Dudden (1905), pages 7-8.

- ↑ Richards (1980), page 44.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Richards (1980), page 26.

- ↑ Ambrosini, Maria Luisa; Mary Willis (1996). The Secret Archives of the Vatican. Barnes & Noble Publishing. pp. 63–64. ISBN 0760701253, 9780760701256.

- ↑ Cantor (1993) page 157.

- ↑ Cantor is a secular observer of Gregory. Cantor dismissed the idea that Jesus thought of himself as the Messiah, writing that "if he thought of himself as a messiah at all, it was in the old sense of a preacher of righteousness or helper of men, rather than of a national saviour against the Romans or the Saviour-God of later Christianity." Cantor also characterizes the time period after the crucifixion and resurrection thus: "The disciples told others about Jesus when there were questioned, and the story began to spread, but their answers did not add up to anything resembling a new religion. Nothing tremendous had happened."(Cantor (1993) page 34-35.)

- ↑ Smith, William; Henry Wace (1880). A Dictionary of Christian Biography, Literature, Sects and Doctrines: Being a Continuation of 'The Dictionary of the Bible': VolumeII Eaba - Hermocrates. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. pp. 415. The dictionary account is apparently based on Bede, Book II, Chapter 1, who used the expression "...impalpable, of finer texture than wind and air."

- ↑ 76:1238‑1246.

- ↑ Pope, H. (2008). "St. Mary Magdalen". The Catholic Encyclopedia (1910). Ed. Kevin Knight. New Advent. Retrieved on 2008-08-23.

- ↑ Filteau, Jerry (2006), "Scholars seek to correct Christian tradition, fiction of Mary Magdalene", Catholic News Service, http://www.catholic.org/national/national_story.php?id=19680, retrieved on 2007-10-01

- ↑ Gietmann, G. (1911), "Nimbus", The Catholic Encyclopedia, XI, New York: Robert Appleton Company

- ↑ Peter the Deacon, Vita, xxviii

- ↑ Catholic Encyclopedia article - see links, below.

- ↑ Bamberg, Staatsbibliothek, MS Msc. Bibl. 84

- ↑ Saraceni, Carlo; Emil Kren; Daniel Marx (1996). "St. Gregory the Great" (html). Web Gallery of Art. Retrieved on 2008-08-23.

- ↑ Dudden (1905) page 316.

- ↑ Later these deacons became cardinals and from the oratories attached to the buildings grew churches.

- ↑ Smith, William; Samuel Cheetham (1875). A dictionary of Christian antiquities: Comprising the History, Institutions, and Antiquities of the Christian Church, from the Time of the Apostles to the Age of Charlemagne. J. Murray. pp. 549 under diaconia.

- ↑ Mann, Horace Kinder; Johannes Hollnsteiner (1914). The Lives of the Popes in the Early Middle Ages: Volume X. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., Ltd.. pp. 322.

- ↑ Ambrosini & Willis (1996) pages 66-67.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Dudden (1905) pages 248-249.

- ↑ Deanesly, Margaret (1969). A History of the Medieval Church, 590-1500. London, New York: Routledge. pp. 22–24. ISBN 0415039592, 9780415039598.

- ↑ Historia Ecclesiastica, II.i.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Hunt, William (1906). The Political History of England. Longmans, Green. pp. 115.

- ↑ The earliest life written a generation earlier than Bede at Whitby relates the same story but in it the English are merely visitors to Rome questioned by Gregory (see Holloway, who translates from the manuscript kept at St. Gallen). The earlier story is not necessarily the more accurate, as Gregory is known to have instructed presbyter Candidus in Gaul by letter to buy young English slaves for placement in monasteries. These were intended for missionary work in England: Ambrosini & Willis (1996) page 71.

- ↑ Benedict I or Pelagius II.

- ↑ Homilies on Ezekiel Book 1.11.6. For the text in manuscript see Codices Electronici Sangalienses: Codex 211, page 193 column 1, line 5 (External links below.)

- ↑ Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Book I section 27 part II. Bede is translated in Bede; Judith McClure, Bertram Colgrave, Roger Collins (editors, translators, contributors) (1999). The Ecclesiastical History of the English People: The Greater Chronicle ; Bede's Letter to Egbert. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192838660, 9780192838667.

- ↑ Champ, Judith (2000). The English Pilgrimage to Rome: A Dwelling for the Soul. pp. ix. ISBN 0852443730, 9780852443736.

- ↑ A monk or nun at Whitby A.D. 713; Julia Bolton Holloway, ed. (1997-2008). "The Earliest Life of St. Gregory the great" (html). Julia Bolton Holloway. Retrieved on 2008-08-10.

- ↑ Sacrosanctum Concilium, 108-111

- ↑ Calendarium Romanum (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 1969), pp. 100 and 118

Bibliography

- Cantor, Norman F. (1993). The Civilization of the Middle Ages. New York: Harper.

- Cavadini, John, ed. (1995). Gregory the Great: A Symposium. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

- Dudden, Frederick H. (1905). Gregory the Great. London: Longmans, Green, and Co.

- Richards, Jeffrey (1980). Consul of God. London: Routelege & Keatland Paul.

- Straw, Carole E. (1988). Gregory the Great: Perfection in Imperfection. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Leyser, Conrad (2000). Authority and Asceticism from Augustine to Gregory the Great. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Markus, R.A. (1997). Gregory the Great and His World. Cambridge: University Press.

- Ricci, Cristina (2002). Mysterium dispensationis. Tracce di una teologia della storia in Gregorio Magno. Rome: Centro Studi S. Anselmo. (Italian). Studia Anselmiana, volume 135.

- Vincenzo Recchia, Lettera e profezia nell'esegesi di Gregorio Magno (Bari: Edipuglia, 2003), Pp. 157 (Quaderni di "Invigilata Lucernis," Dipartamento di Studi Classici e Cristiani, Universita\ degli Studi di Bari, vol. 20).

- George Demacopoulos, Five Models of Spiritual Direction in the Early Church (Notre Dame (IN), University of Notre Dame Press, 2007).

- Hester, Kevin L., Eschatology and Pain in St. Gregory the Great. The Christological Synthesis of Gregory's Morals on the Book of Job (Milton Keynes: Paternoster, 2007), Pp. xv, 155 (Studies in Christian History and Thought).

External links

- "Documenta Catholica Omnia: Gregorius I Magnus" (html). Cooperatorum Veritatis Societas (2006). Retrieved on 2008-08-10. (Latin). Index of 70 downloadable .pdf files containing the texts of Gregory I.

- Gregory the Great (2007). "Homiliae in Ezechielem I-XXII" (in mediaeval Latin written in Carolingian minuscule). Codices Electronici Sangalienses: Codex 211. Stiftsbibliothek St.Gallen. Retrieved on 2008-08-10. Photographic images of a manuscript copied about 850-875 AD.

- Huddleston, Gilbert (2008). "Pope St. Gregory I ('the Great')". The Catholic Encyclopedia (1909). Ed. Kevin Knight. New Advent. Retrieved on 2008-08-10.

- Porvaznik, Phil (July 1995). "Pope Gregory the Great and the 'Universal Bishop' Controversy: Was the Pope denying his own Papal Authority?: Debunking a popular Protestant myth" (html). Apologetics Articles. Phil Porvaznik. Retrieved on 2008-08-10.

- "St Gregory Dialogus, the Pope of Rome" (html). Orthodox Church in America. Retrieved on 2008-08-10. Orthodox icon and synaxarion.

| Roman Catholic Church titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Pelagius II |

Pope 590–604 |

Succeeded by Sabinian |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|||||