Religion in ancient Greece

| Main doctrines | |

| Polytheism · Mythology · Hubris Orthopraxy · Reciprocity · Virtue |

|

| Practices | |

|

Amphidromia · Iatromantis |

|

| Deities | |

| Twelve Olympians: Ares · Artemis · Aphrodite · Apollo Athena · Demeter · Hera · Hestia Hermes · Hephaestus · Poseidon · Zeus --- Primordial deities: Aether · Chaos · Chronos · Erebus Gaia · Hemera · Nyx · Tartarus · Oranos --- Lesser gods: Dionysus · Eros · Hebe · Hecate · Helios Herakles · Iris · Selene · Pan · Nike |

|

| Texts | |

| Argonautica · Iliad · Odyssey Theogony · Works and Days |

|

| See also: | |

| Decline of Hellenistic polytheism Hellenic Polytheistic Reconstructionism Supreme Council of Ethnikoi Hellenes |

Greek religion encompasses the collection of beliefs and rituals practiced in ancient Greece in the form of both popular public religion and cult practices. These different groups varied enough so that one might speak of Greek religions or "cults", though most shared similarities such as a belief in polytheism.

Greek peoples all recognized the 13 major gods and goddess: Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Apollo, Artemis, Aphrodite, Ares, Dionysus, Hephaestus, Athena, Hermes, Demeter, and Hestia, though various lesser gods were also worshipped. Different cities worshipped different deities, sometimes with epithets that specified their local nature.

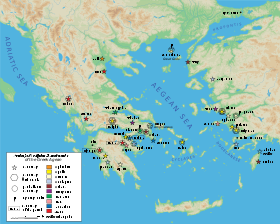

The religious practices of the Greeks extended beyond mainland Greece, to the islands and coasts of Ionia in Asia Minor, to Magna Graecia (Sicily and southern Italy), and to scattered Greek colonies in the Western Mediterranean, such as Massalia (Marseille). Greek religion tempered Etruscan cult and belief to form much of the later Roman religion.

Contents |

Terminology

It is perhaps misleading to speak of "Greek religion." In the first place, the Greeks did not have a term for "religion" in the sense of a dimension of existence distinct from all others, and grounded in the belief that the gods exercise authority over the fortunes of human beings and demand recognition as a condition for salvation. The Greeks spoke of their religious doings as "ta theia" (literally, "things having to do with the gods"), but this loose usage did not imply the existence of any authoritative set of "beliefs." Indeed, the Greeks did not have a word for "belief" in either of the two senses familiar to us. Since the existence of the gods was a given, it would have made no sense to ask whether someone "believed" that the gods existed. On the other hand, individuals could certainly show themselves to be more or less mindful of the gods, but the common term for that possibility was "nomizein", a word related to "nomos" ("custom," "customary distribution," "law"); to nomizein the gods was to acknowledge their rightful place in the scheme of things, and to act accordingly by giving them their due. Some bold individuals could nomizein the gods, but deny that they were due some of the customary observances. But these customary observances were so highly unsystematic.

Beliefs

Whilst there were few concepts universal to all the Greek peoples, there were common beliefs shared by many.

Theology

Ancient Greek theology revolved around polytheism; that is, that there were many gods and goddesses. There was a hierarchy of deities, with Zeus, the king of the gods, having a level of control over all the others. Each deity generally had dominion over a certain aspect of nature, for instance, Poseidon ruled over the sea and earthquakes, and Hyperion ruled over the sun. Other deities ruled over an abstract concept, for instance Eros controlled love.

Whilst being immortal, the gods were not all powerful. They had to obey fate, which overrided all. For instance, in mythology, it was Odysseus' fate to return home to Ithaca after the Trojan War, and the gods could only lengthen his journey and make it harder for him, but they could not stop him.

The gods acted like humans, and had human vices. They would interact with humans, sometimes even spawning children with them. At times certain gods would be opposed to another, and they would try to outdo each other. For instance, in the Trojan war, the god Poseidon supported Troy, but Zeus and Athena supported the Greeks.

Some gods were specifically associated with a certain city. For instance, Athena was associated with the city of Athens, Apollo with Delphi and Delos, Zeus with Olympia and Aphrodite with Corinth. Other deities were associated with nations outside of Greece, for instance, Poseidon was associated with Ethiopia and Troy, and Ares with Thrace.

Identity of names was not a guarantee of a similar cultus; the Greeks themselves were well aware that the Artemis worshipped at Sparta, the virgin huntress, was a very different deity from the Artemis who was a many-breasted fertility goddess at Ephesus. When literary works such as the Iliad related conflicts among the gods these conflicts were because their followers were at war on earth and were a celestial reflection of the earthly pattern of local deities. Though the worship of the major deities spread from one locality to another, and though most larger cities boasted temples to several major gods, the identification of different gods with different places remained strong to the end.

Twelve Olympians

- See Twelve Olympians

The most powerful gods were known as the Olympians, of which there were twelve. They were believed to reside at the top of Mount Olympus. Hades was not included among these twelve because he resided in the Underworld and the god Dionysus lived on the island of Nysa. The twelve deities were:

- Zeus, god of thunder and the sky, and the king of the gods. Husband of Hera, and father to Athena, Apollo, Artemis, Hermes, Persephone, Dionysus and Herakles.

- Hera, goddess of women, marriage and motherhood. Wife of Zeus.

- Poseidon, god of the sea and earthquakes. Consort of Amphitrite the sea goddess, father of Theseus the hero and Triton the sea messenger.

- Demeter, goddess of the harvest, fertility, nature and the seasons. Mother of Persephone the goddess of fertility, Zagreus, Despoina, Arion, Plutus and Philomelus.

- Ares, god of war, frenzy, hatred and bloodshed. Father of Cycnus and Eros the god of love.

- Hermes, god of commerce, thieves and trade. Messenger to the gods. Father of Pan the horned god, Hermaphroditus, Eros, Tyche, Abderus and Autolycus.

- Hephaestus, god of metalcraft, craftsmen, volcanoes and fire. Blacksmith to the gods. Father to King Erichthonius of Athens.

- Aphrodite, goddess of sex, love, beauty and fertility. Mother of Eros the god of love.

- Athena, goddess of wisdom, crafts and strategic battle.

- Artemis, goddess of the hunt, maidens and the moon.

- Hestia, goddess of the hearth and home.

- Apollo, god of the sun, light, healing, the arts, prophecy, the truth and archery.

Lesser deities

Lesser deities, who were in some way related to the Olympians, also existed. One of the most popular was Dionysus (who was commonly called Bacchus), a god of wine and spiritual ectasy, who was a son of Zeus. Another was Pan, a horned god of shepherds and folk music, and Hekate, a goddess of witchcraft and crossroads.

It was possible for a mortal human to become an immortal god. An example of this was Heracles, who was the son of the god Zeus, but who had a mortal mother. By performing great heroic deeds, and through his semi-divine heritage, Herakles eventually became immortal himself[1]. There were also household deities, akin to the Roman lares.

Primordial deities

A third group of deities were the primordial deities. These were considered to be the first deities, such as Chaos, the being of primordial chaos, and Gaia, the goddess of the Earth. Whilst being sometimes worshipped, they were not as popular as the Olympians.

Afterlife

- See Greek Underworld

The Greeks believed in an underworld where the spirits of the dead went to after a funeral. If a funeral was never performed, it was commonly believed that that person's spirit would never reach the underworld and so would haunt the world as a ghost forever. There were various different views of the underworld, and the idea generally changed over time.

One of the most widespread areas of the underworld was known as Hades. This was ruled over by a god, also called Hades. Another realm, called Tartarus, was the place where the damned were thought to go, a place of torment. A third realm, Elysium, was a pleasant place where the virtuous dead and initiaties in the mystery cults were said to dwell. The underworld commonly featured in mythology and literature based thereupon.

Some Greeks, such as the philosophers Pythagoras and Plato, also espoused the idea of reincarnation, though this was not accepted by all.

Mythology

- See Greek mythology

Greek religion had a large mythology. It largely comprised of stories of the gods and of how they affected humans on Earth. Myths often revolved around heroes, and their actions, such as Herakles and his twelve labours, Odysseus and his voyage home, Jason and the quest for the Golden Fleece and Theseus and the Minotaur.

Many different species existed in Greek mythology. Chief among these were the gods and humans, though the Titans also heavily appeared in Greek myths. They predated the Olympian gods, and were hated by them. Lesser species included the half-man, half-horse centaurs, the nature based nymphs (tree nymphs were dryads, sea nymphs were nereids) and the sex-obsessed wildmen satyrs. Some creatures in Greek mythology were monstrous, such as the one-eyed giant Cyclopes, the sea beast Scylla, whirlpool Charybdis and the half-man, half-bull Minotaur.

Many of the myths revolved around the Trojan war between Greece and Troy. For instance, the epic poem, The Iliad, by Homer, is based around the war. Many other tales are based around the aftermath of the war, such as the murder of King Agamemnon of Argos, and the adventures of Odysseus on his return to Ithaca.

There was no one set Greek cosmogony, or creation myth. Different religious groups believed that the world had been created in different ways. One Greek creation myth was told in Hesiod's Theogony. It stated that at first there was only a primordial deity called Chaos, who gave birth to various other primordial gods, such as Gaia, Tartarus and Eros, who then gave birth to more gods, the Titans, who then gave birth to the first Olympians.

The mythology largely survived and was added to in order to form the later Roman mythology. The Greeks and Romans had been literate societies, and much mythology was written down in the forms of epic poetry (such as The Iliad, The Odyssey and the Argonautica) and plays (such as Euripides' The Bacchae and Aristophones' The Frogs). The mythology became popular in Christian post-Renaissance Europe, where it was often used as a basis for the works of artists like Botticelli, Michelangelo and Rubens.

Festivals

Various religious festivals were held in ancient Greece. Many were specific only to a particular deity or city-state. For example, the festival of Lycaea was celebrated in Arcadia in Greece, which was dedicated to the pastoral god Pan.

Morality

One of the most important moral concepts to the Greeks was a fear of committing hubris, which constituted many things, from excessive pride to rape and desecration of a corpse. It was a crime in the city-state of Athens.

Scripture

There was no one core scripture held by all followers of Greek religions, such as the Christian Bible or Islamic Qu'ran.

Practises

Ceremonies

Greek ceremonies and rituals were performed at altars. These typically were devoted to one, or a few, gods, and contained a statue of the particular deity upon it. Votive deposits would be left at the altar, such as food, drinks, as well as precious objects. Sometimes animal sacrifices would be performed here, with most of the flesh eaten, and the offal burnt as an offerring to the gods. Libations, often of wine, would be offered to the gods too, not only at shrines, but also in everyday life, such as during a symposium.

One ceremony was pharmakos, a ritual involving expelling a symbolic scapegoat such as a slave or an animal, from a city or village in a time of hardship. It was hoped that by casting out the ritual scapegoat, the hardship would go with it.

Temples

Often temples were built to the gods. Some of the grandest and most notable were the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, and the Parthenon, dedicated to the goddess Athena upon the Acropolis in Athens.

Temples contained a central room known as a naos, which contained a grand altar and statue of a deity. Priests would be employed to constantly monitor and give offerrings to the deity.

At some of these temples would be located an oracle who could predict the future. The most notable example was the Delphic oracle, who was located at the Temple of Apollo at Delphi.

Rites of Passage

One rite of passage was the amphidromia, celebrated on the fifth or seventh day after the birth of a child.

Mystery religions

Those who were not satisfied by the public cult of the gods could turn to various mystery religions which operated as cults into which members had to be initiated in order to learn their secrets.

Here, they could find religious consolations that traditional religion could not provide: a chance at mystical awakening, a systematic religious doctrine, a map to the afterlife, a communal worship, and a band of spiritual fellowship.

Some of these mysteries, like the mysteries of Eleusis and Samothrace, were ancient and local. Others were spread from place to place, like the mysteries of Dionysus. During the Hellenistic period and the Roman Empire, exotic mystery religions like those of Osiris and Mithras became widespread not only in Greece but all across the empire.

History

Origins

Mainstream Greek religion appears to have evolved from the earlier Mycenaean religion from the Mycenaean civilisation of Bronze Age Greece. The Mycenaeans, according to archaeological discoveries, seemed to treat Poseidon as the chief deity. It may also have absorbed the religions of earlier, nearby religious beliefs and practises, such as Minoan religion.

Classical Antiquity

The pagan religion of the Greeks did not go unchallenged from persons within Greece. Several notable philosophers criticised a belief in the gods. The earliest of these was Xenophanes, who chastised the human vices of the gods as well as their anthropomorphic depiction. Plato did not believe in many polythiestic deities, but instead believed that there was one supreme God, whom he called the Form of the good, and which he believed was the emanation of perfection in the universe. Plato's disciple, Aristotle, also disagreed that polythiestic deities existed, because he could not find enough empirical evidence for it. He was a pandeist, believing in a deity called the Prime Mover, which had set creation going, but was not connected or interested in the universe.

Roman Empire

When the Roman Republic conquered Greece in 146 BC, it took much of Greek religion (along with many other aspects of Greek culture such as literary and architectural styles) and incorporated it into its own. The Greek gods were equated with the ancient Roman deities; Zeus with Jupiter, Hera with Juno, Poseidon with Neptune, Aphrodite with Venus, Ares with Mars, Artemis with Diana, Athena with Minerva, Hermes with Mercury, Hephaestus with Vulcan, Hestia with Vesta, Demeter with Ceres, Hades with Pluto, Tyche with Fortuna, and Pan with Faunus. Some of the gods, such as Apollo and Bacchus, had earlier been adopted by the Romans. There were also many deities that existed in the Roman religion before its interaction with Greece that weren't associated with a Greek deity, including Janus and Quirinus.

Christianization

In the late 4th century CE, the Imperial courts were predominantly Christian, as was the populace; Christianity tolerated relatively few internal quarrels; and a deep conviction that right belief, orthodoxy, was what mattered to God. The Christian emperors closed pagan oracles and temples, and ended the pagan games in a series of increasingly stringent decrees. Finally, the public practice of the Greek religion was made illegal by the Emperor Theodosius I and this was enforced by his successors. The Greek religion, stigmatized as "paganism", the religion of country-folk (pagani)—other scholars suggest the force of paganus was "(mere) civilian"—survived only in rural areas and in forms that were submerged in Christianized rite and ritual, as Europe entered into the Dark Ages.

The European Renaissance scarcely touched Greece. Renaissance humanism in Italy and western Europe included the rediscovery and reintroduction of the culture and learning of ancient Greek thought and philosophy, which included a renewed appreciation of the ancient religion and myth, reinterpreted from a humanist point-of-view.

Neopagan revivals

Greek religion has experienced a number of revivals, in the arts, humanities and spirituality of the Renaissance as well as with the contemporary Hellenic Reconstructionism, or "Hellenismos" as it is sometimes called (a term first used by the last pagan Roman emperor Julian the Apostate).

Many neo-pagan religious paths, such as Wicca, use aspects of ancient Greek religions in their practice; Hellenic Reconstructionism focuses exclusively thereon, as far as the nature of the surviving source material allows. It reflects neo-Platonic/Platonic speculation (which is represented in Porphyry, Libanius, Proclus, and Julian), as well as Classical cult practice.

The overwhelming majority of modern Greeks are followers of Greek Orthodox Christianity. According to estimates, there are perhaps as many as 45,000 followers of the ancient Greek religion out of a total Greek population of 10 million. The Neopagan revival is limited largely to the transient communities of the Greek islands and isolated mountain villages of the Pindos range and Western Macedonia .

Notes

-

1 Martin Litchfield West, The Orphic Poems, p.148, cf. Figure 2, entitled "Patterns of Shamanistic influence in Bronze Age and Archaic Greece" - a map showing the migration of Central Asian shamanism to the Greek colony of Olbia in Scythia (now in Ukraine), down to Proconnesus, then down to Samos. On p.146, West writes: "There is reason to believe that in classical times, Shamanistic practice and ideology extended across the Steppes into the northern territories of the Indo-European tribes, from Northwest India and Bactria to Scythia to Thrace. It is also in Ionia that we located the development in the sixth century [BC] of an ecstatic Bacchic cult which adopted Orpheus as its prophet (as also did Pythagoras). And we saw that this cult flourished right on the northern shore of the Black Sea, at Olbia, where a Scythian King participated in it (pp.17-18). One is led to wonder how much of the shamanistic influence which we detect in the culture of the archaic Ionians came to them in fact from their own Pontic colonies, and the direct contact with the Scyths which they had there." West then cites some works, including Shamanism by Mircea Eliade, pp. 390-1, 394-421 and Scythica by Karl Meuli.

-

2 M.L. West, ibid., p.17. "In another place Herodotus tells us of a cult of Dionysos Baccheios, Dionysos of the Bacchoi, at Borysthenes (Olbia), one of the noteworthy of all Greek colonies".

-

3 Xavier Riu, Dionysism and Comedy, p. 104, "Dionysus comes from the Outside-- the other world".

-

5 Malcolm Brabant, "Zeus devotees worship in Athens", http://news.bbc.co.uk+(2007-01-27). Retrieved on 2007-01-24.

References

- Albertus Bernabé (ed.), Orphicorum et Orphicis similium testimonia et fragmenta. Poetae Epici Graeci. Pars II. Fasc. 1. Bibliotheca Teubneriana, München/Leipzig: K.G. Saur, 2004. ISBN 3-598-71707-5. review of this book

- Walter Burkert, Greek Religion. Boston: Harvard University Press, 1987. ISBN 0-674-36281-0. Widely regarded as the standard modern account.

- Walter Burkert, Homo necans, 1972.

- Cook, Arthur Bernard, Zeus: A Study in Ancient Religion, (3 volume set), (1914-1925). New York, Bibilo & Tannen: 1964. ASIN B0006BMDNA

- Dodds, Eric Robertson, The Greeks and the Irrational, 1951.

- Mircea Eliade, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, 1951.

- Lewis Richard Farnell, Cults of the Greek States 5 vols. Oxford; Clarendon 1896-1909. Still the standard reference.

- Lewis Richard Farnell, Greek Hero Cults and Ideas of Immortality, 1921.

- Jack Finegan, Myth and Mystery: An Introduction to the Pagan Religions of the Biblical World, 1989. ISBN 0-8010-2160-X

- George Grote, A History of Greece: From the earliest period to the close of the generation contemporary with Alexander the Great, 1846.

- Jane Ellen Harrison, Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion, 1903. An early classic, against which many modern accounts have reacted.

- Jane Ellen Harrison, Themis: A Study of the Social Origins of Greek Religion, 1912. [2]

- Jane Ellen Harrison, Epilegomena to the Study of Greek Religion, 1921.

- Karl Kerényi, The Gods of the Greeks

- Karl Kerényi, Dionysus: Archetypical Image of Indestructible Life

- Karl Kerényi, Eleusis: Archetypal Image of Mother and Daughter. The central modern accounting of the Eleusinian Mysteries.

- Karl Meuli, Scythica, 1935.

- Jon D. Mikalson, Athenian Popular Religion. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1983. ISBN 0-8078-4194-3.

- William Mitford, The History of Greece, 1784. Cf. v.1, Chapter II, Religion of the Early Greeks

- Clifford H. Moore, The Religious Thought of the Greeks, 1916.

- Martin P. Nilsson, Greek Popular Religion, 1940. [3]

- Martin P. Nilsson, History of Greek Religion, 1949.

- Robert Parker, Athenian Religion: A History Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996. ISBN 0-19-815240-X.

- Andrea Purvis, Singular Dedications: Founders and Innovators of Private Cults in Classical Greece, 2003.

- William Ridgeway, The Dramas and Dramatic Dances of non-European Races in special Reference to the Origin of Greek Tragedy, with an Appendix on the Origin of Greek Comedy, 1915.

- William Ridgeway, Origin of Tragedy with Special Reference to the Greek Tragedians, 1910.

- Xavier Riu, Dionysism and Comedy, Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 1999. ISBN 0-8476-9442-9.

- Erwin Rohde, Psyche: The Cult of Souls and Belief in Immortality among the Greeks, 1925.

- William Smith, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, 1870, [4]

- William Smith, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, 1870. [5]

- Martin Litchfield West, The Orphic Poems, 1983.

- Martin Litchfield West, Early Greek philosophy and the Orient, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1971.

- Martin Litchfield West, The East Face of Helicon: west Asiatic elements in Greek poetry and myth, Oxford [England] ; New York: Clarendon Press, 1997.

|

||||||||||||||||||||