Flag of Greece

|

|

| Use | National flag and ensign. |

| Proportion | 2:3 |

| Adopted | December 22, 1978 (Naval Flag 1822-1828, Sea Flag 1828-1969, National Flag 1969-1970; 1978 to date) |

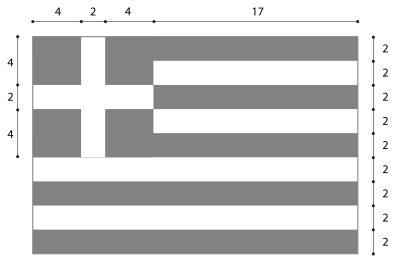

| Design | Nine horizontal stripes, in turn blue and white; a white cross on a blue square field in canton. |

The flag of Greece (Greek: Σημαία της Ελλάδος, popularly referred to as the Γαλανόλευκη or the Κυανόλευκη, the "blue-white") is based on nine equal horizontal stripes of blue alternating with white. There is a blue canton in the upper hoist-side corner bearing a white cross; the cross symbolises Greek Orthodoxy, the established religion of the people of Greece. According to popular tradition, the nine stripes represent the nine syllables of the phrase "Ελευθερία ή Θάνατος" ("Freedom or Death", " E-lef-the-ri-a i Tha-na-tos"), the five blue stripes for the syllables "Έλευθερία" and the four white stripes "ή Θάνατος". There is also a different theory, that the nine stripes symbolize the nine Muses, the goddesses of art and civilization (nine has traditionally been one of the numbers of reference for the Greeks).[1] The official flag ratio is 2:3.[2]

The blazon of the flag is Azure, four bars Argent; the canton Azure with a Greek cross throughout Argent. The shade of blue used in the flag has varied throughout its history, from light blue to dark blue, the latter being increasingly used since the late 1960s.

The above patterns were officially adopted by the First National Assembly at Epidaurus on 13 January 1822. Blue and white have many interpretations, symbolizing the colours of the famed Greek sky and sea (combined with the white clouds and waves), traditional colours of Greek clothes in the islands and the mainland, etc.

|

|

History of the Greek flag

- See also: List of Greek flags

The origins of today's national flag with its cross-and-stripe pattern are a matter of debate. Every part of it, including the blue and white colours (see below), the cross, as well as the stripe arrangement can be connected to very old historical elements; however it is difficult to establish "continuity", especially as there is no record of the exact reasoning behind its official adoption in early 1822.

The formation of blue and white stripes (created from placing white metal stripes on a blue surface) on Achilles's shield resulting in 9 lines, with all the significance of this number to Greeks, has also been used as an argument for the historic significance of the flag [3]. Nonetheless, flags with stripes had been used before 1822, especially as sea flags (as the original use of the particular flag was meant to be). It has been suggested that the exact 1822 pattern evolved from an older design, a virtually identical flag of the powerful Cretan Kallergis family (who provided several military and political figures in Greek history). The flag was based on their coat of arms, whose pattern in turn is allegedly derived from the standards of their ancestor, Byzantine Emperor Nicephorus II Phocas (963-969 AD). This pattern included the nine stripes of alternating blue and white, and the cross on the canton.

The stripe-pattern of the Greek flag is visibly similar to that used in several other flags that have appeared over the centuries, most notably that of the British East India Company's pre-1707 flag. However, in such cases of flags derived from much older designs, it is very difficult to prove or trace original influences.

It is quite possible, nevertheless, that foreign flags such as that of the United States of America may have influenced the preferential adoption of the stripe-pattern, apparently already existing, as the Greek sea flag.

Greek flags during Antiquity and the Byzantine Empire

White and blue have been symbolic Greek colors since antiquity with historic significance [5]; their adoption for the new Greek state was a natural continuation from previous uses. In ancient Greece they were connected with goddess Athena and were used in Alexander the Great's army banners,[6] while Greeks abroad were often recognized by their white clothes with blue details [5]. During Byzantine times white and blue were the colors of navy and other flags (including in same cases the Devilion, the official flag of the Imperial Guard, being the closest to a "state flag") [3], coats of arms of imperial dynasties, uniforms, Emperors' clothes, Patriarchs' thrones etc [5][6]. The cross, along with the Chi-Rho, was a symbol of the empire, and was a common pattern in Byzantine flags since the Christianisation of the Roman Empire in the 4th century. Blue and white Byzantine naval flags with blue cross on a white field (presumably 4th century AD) or white cross on a blue field (10th century AD) are exhibited (reconstructed) in the Greek Naval Museum in Piraeus.

An important Byzantine symbol, used since the early centuries of the Empire [7] but more extensively used as the dynastic arms by the Palaiologan emperors, is the so-called "tetragrammatic cross", with four Bs or pyrekvola ("fire-steels") on the flag quarters representing the imperial motto Βασιλεύς Βασιλέων Βασιλεύων Βασιλευόντων ("King of Kings Reigning over those who Rule"), at times also interpreted as standing for Βασιλεύ Βασιλέων Βασιλέα Βοήθει ("King of Kings, Aid the Emperor")[8].

Ottoman period

During the Ottoman rule several unofficial flags were used by Greeks, usually employing the double-headed eagle (see below), the cross, depictions of saints and various mottoes. The Greek Spachides cavalry employed by the Ottoman Sultan were allowed to use their own, clearly Christian flag, when within Epirus and the Peloponnese. It featured the classic blue cross on a white field with the picture of St. George slaying the dragon, and was used from 1431 until 1639, when this privilege was greatly limited by the Sultan. Similar flags were used by other local leaders. The closest to a Greek "national" flag during Ottoman rule was the Graikothomaniki pantiera, a civil ensign Greek Orthodox merchants were allowed to fly on their ships, combining stripes with red (for the Ottoman Empire) and blue (for the Greeks) colors. After the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca, Greek-owned merchant ships could also fly the Russian flag.

During the uprising of 1769 the historic blue cross on white field was used again by key military leaders who used it all the way to the revolution of 1821. It became the most popular Revolution flag, and it was argued that it should become the national flag. The "reverse" arrangement, white cross on a blue field, also appeared as Greek flag during the uprisings. This design had been used earlier as well, as a local symbol (a similar 16th or 17th century flag has been found near Chania), while Greek volunteers in Napoleon's army in Egypt in 1798 used a white cross on blue incorporated in the canton of the French flag [7].

A military leader, Yiannis Stathas, used a flag with white cross on blue on his ship since 1800. The first flag featuring the design eventually adopted was created and hoisted in the Evangelistria monastery in Skiathos in 1807. Several prominent military leaders (including Theodoros Kolokotronis and Andreas Miaoulis) had gathered there for consultation concerning an uprising, and they were sworn to this flag by the local bishop.

Adoption of the flag and historical evolution

In addition to the various cross flags, Greek intellectuals in Europe, as well as local leaders, chieftains and regional councils, designed and used flags with different colours and emblems during the early days of the Greek Revolution. Many of these flags featured saints, the phoenix (symbolizing the rebirth of the Greek nation), mottoes such as "Freedom or Death" (Ελευθερία ή Θάνατος) or the fasces-like emblems of the Philiki Etaireia.

Because the European monarchies, allied in the so-called "Concert of Europe", were suspicious towards national or social revolutionary movements such as the Etaireia, the First Greek National Assembly, convening in January 1822, took steps to portray revolutionary Greece as a "conventional", ordered nation-state. As such not only were the regional councils abolished in favour of a central administration, but it was decided to abolish all revolutionary flags and adopt a national flag. Why the particular arrangement (white cross on blue) was selected instead of the more popular blue cross on a white field, remains unknown.

On March 15 1822, the Provisional Government, by Decree Nr. 540, laid down the exact pattern: white cross on blue (plain) for the land flag; nine alternate-coloured stripes with the white cross on a blue field in the canton for the naval flag; and blue cross on white in the canton of an otherwise blue flag, for the merchant navy.[2] In 1828 the latter was discontinued, and the cross-and-stripes became the sole sea flag. This design became immediately very popular with Greeks and in practice was often used simultaneously with the national (plain cross) flag.

King Otto added the royal Coat of Arms (a shield in the Bavarian colors topped by a crown) to the center of the cross for military flags (both land and sea versions).[2] After Otto's abdication in 1862, the royal coat of arms was removed, only to be replaced by a simple royal crown in 1863. A square version of the land flag with St. George in the center was adopted in April 9 1864 as the Army's colours. Similar arrangements were made for the royal flags, which featured the coat of arms of the House of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg on a square version of the national flag. The exact shape and usage of the flags was determined by Royal Decree on September 27 1867. By a new Royal Decree, on 31 May 1914, the flag with the crown was adopted for use as a state flag by ministries, embassies and civil services, while the merchant naval flag was allowed for use by private citizens.

On March 25 1924, with the establishment of the Second Hellenic Republic, the crowns were removed from all flags. On February 20 1930, the national flag's proportions were established at a 2:3 ratio, with the arms of the cross being "one fifth of the flag's width". The national ("land") flag was to be used by ministries, embassies, and in general by all civil and military services, while the naval flag was to be used by naval and merchant vessels, consulates and private citizens. With the restoration of the monarchy, on October 10 1935, the crown was restored on the flags. The crown was again removed by the military dictatorship in 1967, and the naval flag was established as the sole national flag in 1969, using a dark shade of blue. On August 18 1970, the flag ratio was changed to 7:12.

After the metapolitefsi, the land flag was restored for a while (Law 48/1975 and Presidential Decree 515/1975) until 1978.

The current Flag of Greece

In 1978 the former civil ensign (sea flag) was adopted as the sole national flag, with a 2:3 dimension ratio. [9] The current flag is used on land and is also the war and civil ensign replacing all other designs surviving until that time. No other designs and badges can be shown on the flag. The Greek Flag Day is on October 27.

The old land flag is still flown at the Old Parliament building in Athens, site of the National Historical Museum, and can still be seen displayed unofficially by private citizens.

To date, no specification of the exact shade of the blue colour of the flag has been issued. In practice, hues may vary from very light to very dark.

Greek War flag

The War flag (equivalent to regimental colours) of the Army and the Air Force is of square shape, with a white cross on blue background. On the center of the cross the image of Saint George is shown on Army flags and the image of archangel Michael is shown on Air Force flags.[2]. In the Army war flags are normally flown by infantry and tank regiments and the military academy when in battle or in parade. Units of Naval or Coast Guard personnel in parade fly the war ensign in place of the war flag.[10] There was also provision for a war flag for the semi-military Hellenic Gendarmerie, which was later merged with Cities Police to form the current Hellenic Police.

Since the Fire Service, the Hellenic Police and the former Cities Police are considered civilian agencies, they are not assigned war flags, instead they are using the National Flag.[11]

The naval and civil ensigns are identical to the national flag.

The simple white cross on blue field pattern is also used as the Navy's jack and in naval rank flags. These flags are described in Chapter 21 (articles 2101-2130) of the Naval Regulations.

The double-headed eagle

It may look surprising that one of the most recognizable (other than the cross) and beloved Greek symbols, the double-headed eagle, is not a part of the modern Greek flag or coat of arms (although it is officially used by the Greek Army, by the Church of Greece, and was incorporated in the Greek coat of arms between 1925 and 1926). One suggested explanation is that, upon independence, an effort was made for political - and international relations - reasons to limit expressions implying efforts to recreate the Byzantine empire. Yet another theory is that this symbol was only connected with a particular period of Greek history (Byzantine) and a particular form of rule (imperial). More recent research has justified this view, connecting this symbol only to personal and dynastic emblems of Byzantine Emperors.

Greek scholars have attempted to establish links with ancient symbols: the eagle was a common design representing power in ancient city-states, while there was an implication of a "dual-eagle" concept in the tale that Zeus left two eagles fly east and west from the ends of the world, eventually meeting in Delphi, thus proving it to be the center of the earth. However, there is virtually no doubt that its origin is a blend of Roman and Eastern influences. Indeed, the early Byzantine Empire inherited the Roman eagle (extended wings, head facing right) as an imperial symbol. During his reign, Emperor Isaac I Comnenus (1057–1059) modified it as double-headed, influenced by traditions about such a beast in his native Paphlagonia in Asia Minor (in turn reflecting possibly much older local myths). Many modifications followed in flag details, often combined with the cross. After the recapture of Constantinople by the Byzantine Greeks in 1261, two crowns were added (over each head) representing - according to the most prevalent theory - the newly recaptured capital and the intermediate "capital" of the empire of Nicaea. There has been some confusion about the exact use of this symbol by the Byzantines; it is quite certain that it was a "dynastic" and not a "state" symbol (a term not fully applicable at the time, anyway), and for this reason, the colours connected with it were clearly the colours of "imperial power", i.e., imperial purple and gold.

After the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople nonetheless, the double-headed eagle became a strong "national" symbol of reference for the Greeks (much less, though, than the cross), featured in several flag designs, especially during uprisings and revolts. Most characteristically, the Orthodox Church kept, and is to this date still using Byzantine flags with the eagle, usually black on yellow/gold background. But after the Ottoman conquest this symbol also found its way to a "new Constantinople" (or Third Rome), i.e. Moscow. Russia, deeply influenced by the Byzantine Empire, saw herself as its heir and adopted the double-headed eagle as its imperial symbol. It was also adopted by the Serbs, the Montenegrins, the Albanians and a number of Western rulers, most notably in Germany and Austria.

See also

- Hymn to Liberty

- Byzantine heraldry

- History of Greece

Notes/References

- ↑ Official site of the Greek Army: Η καθιέρωση της ελληνικής σημαίας.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 The Flag, from the site of the Presidency of the Hellenic Republic

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 V. Tzouras, "The Greek Flag, Original Historic Study", A. Lantzas, Kerkyra 1909 (a very important work, on which several other books have been based)

- ↑ Ottfried Neubecker, Heraldry - Sources, Symbols and Meaning, pp.106, Tiger Books International (Twickenham), 1997.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 N. Zapheiriou, "The Greek Flag from Antiquity to Present", Eleutheri Skepsis, Athens 1995 (reprint of original 1947 publication)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 E. Kokkoni and G. Tsiveriotis, "Greek Flags, Signs and Emblems", Athens 1997

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 History of Greek Flags

- ↑ Byzantine Heraldry, from Heraldica.org

- ↑ Law 851/21-12-1978 On the national Flag, War Flags and the Distinguishing Flag of the President of the Republic, Gazette issue A-233/1978.

- ↑ Presidential Decree 348 /17-4-1980, On the war flags of the Armed Forces and the Gendarmerie Corps, Gazette issue A-98/1980.

- ↑ Presidential Decree 991/7-10-1980, Specification of the size of the National Flag born by the Coast Guard, Cities Police and Fire Service and the length of its staff, Gazette issue A-149/1980.

Additional references

- I. Nouchakis, "Our Flag", Athens 1908.

External links

- Presidency of the Hellenic Republic: State Symbols, The Flag

- Greece: Index of all related pages at Flags of the World

- Article on the Greek Flag from the website of the Hellenic Army (in Greek)

- Older article on the Greek Flag from the website of the Hellenic Army (in Greek)

- Greek flags during the Ottoman era (in Greek)

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||