Greek Cypriots

| Part of a series on |

| Greeks |

|

| By region or country |

| Greece · Cyprus Greek diaspora |

| Subgroups |

| Antiochians · Aromanians · Arvanites Cypriots · Epirotes · Karamanlides Maniots · Phanariotes · Pontians Romaniotes · Sarakatsani · Sfakians Slavophones · Souliotes · Tsakonians Urums |

| Greek culture |

| Art · Cinema · Cuisine · Dance Dress · Education · Flag · Language Literature · Music · Philosophy · Politics Religion · Sport · Television |

| Religion |

| Greek Orthodox Church Greek Roman Catholicism Greek Byzantine Catholicism Greek Evangelicalism Judaism · Islam · Neopaganism |

| Languages and dialects |

| Greek Calabrian Greek · Cappadocian Greek Cretan Greek · Griko · Cypriot Greek Maniot Greek · Pontic Greek · Tsakonian Yevanic · Aromanian · Arvanitika Meglenitic · Slavika · Urum |

| History of Greece |

Greek Cypriots (Greek: Ελληνοκύπριοι, Turkish: Kıbrıslı Rumlar) are the ethnic Greek population of Cyprus. They form the island's largest ethnic community, comprising nearly 80 percent of the population. The Greek Cypriots are mostly Eastern Orthodox Christians, members of the Orthodox Church of Cyprus, an autocephalous church headed by an Archbishop. In a broader sense the term also includes Maronites, Armenians and Latins who were given the option of adhering to one of two constituent communities (Greek or Turkish) per the 1960 Constitution and who voted to join the Greek Cypriot Community.

Contents |

History

The Greek Cypriots trace their origins to the descendants of the Achaean Greeks and later the Mycenaean Greeks who settled on the island during the second half of the second millennium BC. The island gradually became part of the Hellenic world as the settlers prospered over the next centuries. Alexander the Great liberated the island from the Persians in 333 BC. After the division of the Roman Empire in 285 AD, Cypriots enjoyed home rule almost nine centuries under the jurisdiction of the Byzantine Empire, something not seen again until 1960. Perhaps the most important event of the early Byzantine period was that the Greek Orthodox Church of Cyprus became an independent autocephalous church in 431.

The Byzantine era profoundly molded Greek Cypriot culture. The Greek Orthodox Christian legacy bestowed on Greek Cypriots in this period would live on during the succeeding centuries of foreign domination. Because Cyprus was never the final goal of any external ambition, but simply fell under the domination of whichever power was dominant in the eastern Mediterranean, destroying its civilization was never a military objective or necessity.

The Cypriots were though faced with the heavy oppressive rule of first the Lusignans and then the Venetians from the 1190s through, to 1570. Especially Guy de Lusignan's brother Amaury, who succeeded him in 1194, was very intolerant of the Orthodox Church. Cypriot Greeks' land was appropriated for the Latin churches after they were established in the major towns on the island. In addition, tax collection was also part of the heavy oppressive attitude of the occupiers to the locals of the island, in that it was now being conducted by the Latin churches themselves.

Ottoman's conquest of Cyprus in 1571, saved the Greek population from serfdom, and servitude to the Latin church. Cypriot Greeks were now able to take control of their land they had been working on for centuries. The local Christians resumed practicing their religion in the only acceptable way they knew. The patriarch serving the Ottoman king also acted as an ethnarch, a leader of the nation, thus enabling the local Orthodox representative to practice secular powers, for instance in adjudicating justice and in the collection of taxes.

Despite the heavy oppression the period of Ottoman occupation (1570-1878) did little to change Greek Cypriot culture outright. The Ottomans tended to administer their multicultural empire with the help of their subject millets, or religious communities. The tolerance of the millet system permitted the Greek Cypriot community to survive, administered for Istanbul by the Archbishop of the Orthodox Church of Cyprus, who became the community's head, or ethnarch. Although tolerant, Ottoman rule was generally harsh and inefficient. Turkish settlers suffered alongside their Greek Cypriot neighbors, and the two groups endured together centuries of oppressive governance from Istanbul.

Cypriot cuisine, as with Greek cuisine, was imprinted with the spices and herbs made common as a result of extensive trade links within the Ottoman empire. Names of many dishes came to reflect the sources of the ingredients from the many lands under the Ottoman rule. Coffee houses pervasively spread throughout the island into all major towns and countless villages.

Politically, the concept of enosis - unification with the Greek "motherland" - became important to literate Greek Cypriots after Greece gained its independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1821. A movement for the realization of enosis gradually formed, in which the Orthodox Church of Cyprus had a dominant role (see "Cyprus dispute").

During British rule (1878-1960), the British brought an efficient colonial administration, but government and education were administered along ethnic lines, accentuating differences. For example, the education system was organized with two Boards of Education, one Greek and one Turkish, controlled by Athens and Istanbul, respectively. The resulting education emphasized linguistic, religious, cultural, and ethnic differences and ignored traditional ties between the two Cypriot communities. The two groups were encouraged to view themselves as extensions of their respective motherlands, and the development of two distinct nationalities with antagonistic loyalties was ensured.

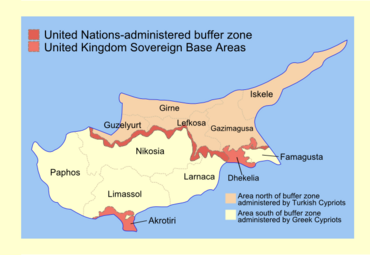

The importance of religion within the Greek Cypriot community was reinforced when the Archbishop of the Church of Cyprus, Makarios III, was elected the first president of the Republic of Cyprus in 1960. For the next decade and a half, enosis was a key issue for Greek Cypriots, and a key cause of events leading up to 1974 when Turkey invaded and occupied the northern part of the island. The island remains divided today, with the two communities almost completely separated. Many Greek Cypriots, most of which lost their homes, lands and possessions during the Turkish invasion emigrated mainly to the UK, Australia and Europe. There are today over 200,000 Greek Cypriots emigrants living in Great Britain.

By the early 1990s, Greek Cypriot society enjoyed a high standard of living. Economic modernization created a more flexible and open society and caused Greek Cypriots to share the concerns and hopes of other secularized West European societies. The Republic of Cyprus joined the European Union in 2004, officially representing the entire island, but suspended for the time being in the Turkish occupied north.

Greek Cypriot dialect

The Greek Cypriot dialect is a member of the south-eastern group of dialects and idioms of the Modern Greek language. It shares common characteristics with the idioms of the Dodecanese islands as well as those of Asia Minor. The dialect does not have a common form but is divided into a number of distinct local variations.

In recent times, especially due to demographic changes that arose after the Turkish Invasion of Cyprus, the Cypriot dialect has largely merged with the formal Modern Greek language both in terms of syntax and to a great extent in terms of form and vocubulary. In the most part, the dialect now survives and is differentiated from the formal Modern Greek only in its phonology.[1]

See also

- Turkish Cypriots

- Greek Britons

External links

- Oral Histories of Greek Cypriots who Migrated to Great Britain (1930-1960)

- Reassessing what we collect website – Greek Cypriot London History of Greek Cypriot London with objects and images

- Cyprus: Historical Setting

References

The Ottoman Empire 1700–1922, Donald Quataert, ISBN 0521839106

- ↑ Istoria tis Kypriakis Dialektou, Charalampos Symeonidis, Kentro Meleton Ieras Monis Kykkou, Nicosia 2006