Greco–Persian Wars

For other Persian wars, see Roman-Persian Wars, Arab-Persian Wars, Persian Gulf Wars, and Military history of Iran.

| The Greco-Persian Wars | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Map of the Persian offensive phase of the Greco-Persian Wars |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Greek city states led by Athens and Sparta (not including Epirus, Lokris, Achaea and Argos) | Persian Empire and allies (including Thessaly, Boeotia, Thebes, Macedon, and Phoenicia) | ||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| Miltiades, Themistocles, Eurybiades, Leonidas I †, Pausanias, Cimon †, Pericles |

Darius I, Mardonius †, Datis †, Artaphernes, Xerxes I, Artabazus, Megabyzus, Hydarnes |

||||||

|

|||||

The Greco-Persian Wars were a series of conflicts between several Greek city-states and the Persian Empire that started in 499 BC and lasted until 448 BC. The expression "Persian Wars" usually refers to both Persian invasions of the Greek mainland in 490 BC and in 480-479 BC; in both cases, the allied Greeks successfully repelled the invasions.[2] Not all Greek city-states fought against the Persians; some were neutral and others allied with Persia, especially as its massive armies approached.

Historical Sources

What is known of this conflict today comes almost exclusively from the Greek sources. Herodotus of Halicarnassus after his exile from his home town, in the middle of the 5th century BC travelled all over the Mediterranean and beyond, from Scythia to Egypt collecting information over the Persian Wars and other events that he complied in his book Ιστοριης Απόδειξη (known in English as The Histories). He begins with Croesus's conquest of Ionia[3] and ends with the fall of Sestus in 479 BC.[4] He is believed to repeat what was told to him by his hosts and sponsors without subjecting it to critical control, thus giving us at times the truth, at times exaggerations and at times political propaganda. However, ancient writers consider his work much better in quality than that of any of his predecessors which is why Cicero called him father of history.[5]

Thucydides the Athenian intended to compile a work from where Herodotus ends until the end of the Peloponnesian War in 404 BC. His collection of books is entitled Ξυγγραφη (known in English as The Peloponnesian War). It is believed that he died before completing his work, as he gives a full account only of the first twenty years of the Peloponnesian War. There is little information on what happened before. The events that interest us here are recounted in Book I paragraphs 89 to 118.

Among later writers Ephorus wrote in the 4th century BC a universal history which includes the events of these wars. Diodorus Siculus wrote in the 1st century AD a book of history since the beginning of time that also includes the history of this war. The closest thing to a Persian source in Greek literature is Ctesias of Cnedus who was Artaxerxes Mnemon's personal physician wrote a history of Persia according to Persian sources in the 4th century BC. In his work he also mocks Herodotus and claims that his information is accurate since he heard from the Persians. Unfortunately the works of these last writers have not survived complete. Since fragments of them are given in the Myriobiblon which was compiled by Photius that later became Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople in the 9th century AD, in the book Eklogai by the emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitos (913-919 AD) and the Suda dictionary 10th century AD it is believed that they were lost with the destruction of the imperial library of the Holy Palace of Constantinople by the crusaders of the Fourth Crusade in 1204.

Thus historians are forced to supplement Herodotus' and Thucydides' information with works of later writers intended for other uses like 2nd century AD Plutarch's biographies and the tour guide of southern Greece compiled at the same time by the geographer and traveller Pausanias, who is not to be confused with the Spartan general of the same name mentioned later. Some Roman historians in their works give account of this conflict. Justinus who information, as are in Cornelius Nepos's Biographies.

Origins of the conflict

The Greeks, the Lydians, and the Persians

The Lydians of Western Asia Minor were the first nations to conquer the Asiatic Greeks. Alyattes II first made war on Miletus which ended with a treaty of alliance between Miletus and Lydia,[6] which meant that Miletus would have internal autonomy but follow Lydia in foreign affairs. Thus they sent an army to aid him in his war against the Medes. During a battle between the Lydians and the Medes a total solar eclipse took place, believed to be that of May 28 585 BC, which had been predicted by Thales the Milesian.The battle was suspended out of alarm, peace was signed that was strengthened by a royal marriage, and the river Halys was set up as the frontier between the Lydians and the Medes.[7] Croesus succeeded his father in 560 BC and made war on the other Greek city states of Asia Minor. He conquered them and forced them to pay tribute but did not extend his realm to the islands of the Aegean.[8]

Cyrus the Great rebelled against the Medes in 554 BC/553 BC[9] and after four years conquered the Medes and founded the Persian Empire. Croesus saw this as an opportunity to extend his realm and asked the oracle of Delphi whether he should make war. The Oracle replied with one of its more famous answers, that if Croesus was to cross the river Halys he would destroy a great empire.[10] Croesus did not realise the ambiguity of the statement and marched to war but was defeated and his capital fell to Cyrus.[11] The Greek city-states then sent messenger to Cyrus asking to have the same terms as under Croesus but, with the exception of Miletus, Cyrus refused, saying they should have asked while the outcome of the war was undecided, as had Miletus.[12] Cyrus then conquered Assyria[13] before he died. His successor Cambyses II

- regarded the Ionians and Aiolians; and he proceeded to march an army against Egypt, taking with him as helpers not only the other nations of which he was the ruler, but also those of the Hellenes over whom he had power besides (Herodotus II,1 translated by G. C. Macaulay)

Persian satraps of Asia Minor installed tyrants in most of the Ionian cities and forced Greeks to pay taxes. The campaign against Egypt in 525 BC was successful when the Cypriot cities,[14] Polycrates of Samos[15] (both of whom had a fleet) and the leader of the Greek mercenaries of Egypt Phanes of Halicarnassus came to his side.[16] This conquest increased discontent with the Persians due to a reduction in trade because Phoenicians, who had willingly joined the Persian empire earlier[17] took part of the market. Furthermore the fall of the Greek colony Sybaris in Southern Italy in 510 BC closed the western markets for the Ionian city-states.[18] In the mean time Darius the Great, Cambyses' successor conquered Libya and part of India, thus creating a massive empire.

Ionian Revolt

The Ionian Revolts were triggered by the actions of Aristagoras, the tyrant of the Ionian city of Miletus at the end of the 6th century BC and the beginning of the 5th century BC. They constituted the first major conflict between Greece and Persia. Most of the Greek cities occupied by the Persians in Asia Minor and Cyprus rose up against their Persian rulers. The war lasted from 499 BC to 493 BC. The Ionians had early success with the sack of Sardis but the ensuing Persian counterattack by both the army and navy was too strong and the Ionians were decisively defeated at the Battle of Lade off the coast of Miletus in 494 BC.

First invasion of Greece

By 493 BC, the last holdouts of the rebellion were subjugated by the Persian fleet, containing ships from Egypt and Phoenicia.The revolt was used as an opportunity by Darius the Great to extend the empire's border to the islands of the East Aegean and the Propontis, many of which had not been under the Persians before.[19] While the Ionian city of Miletus was sacked, its temples stripped and population resettled,[20] the other Ionian city-states found the Persians surprisingly conciliatory in the wake of the rebellion. Darius took direct control of the resettlement of the region through his son-in-law Mardonius. The flat-tribute system was replaced with a progressive tax based on the land-holdings of each city, democracies were established in some, if not all, of the Ionian city-states, prisoners were reintegrated into their home cities, and Darius actively encouraged the Persian nobility of the area to participate in Greek religious practices, especially those dealing with Apollo.[21] Records from the period indicate that the Persian and Greek nobility began to intermarry, and the children of Persian nobles were given Greek names instead of Persian names. Darius' conciliatory policies were used as a type of propaganda campaign against the mainland Greeks, so that in 491 BC, when Darius sent heralds throughout Greece demanding submission (earth and water), initially most city-states accepted the offer, Athens and Sparta being the most prominent exceptions.[22]

Mardonius' Campaign

In the spring of 492 BC, an expeditionary force commanded by Darius' son-in-law Mardonius was assembled in Cilicia. The objective was to subdue as many as they could of the Hellenic cities. Mardonius sent his army to the Hellespont while he took the fleet up the Aegean coast to Ionia. There he removed the tyrants and established popular governments in the Ionian cities.[23]

From thence Mardonius continued on to the Hellespont and when his army and fleet had been assembled crossed the Hellespont into Thrace and Macedon, (both of which had been previously part of the Persian Empire before the Ionian revolt), subjugating all the people on his path. Thrace, which surrendered without defending themselves, was reorganized as a satrapy, and Macedonia was reduced from an ally to a client state.

The Vrygians, a local Thracian tribe, offered the strongest resistance, even managing in a daring night raid to wound Mardonius, but were eventually subjugated.[24]

Meanwhile the fleet conquered Thassos and reached Acanthus (in the isthmus of the Athos peninsula) but while attempting to round the peninsula was nearly destroyed in a storm off Mt. Athos. 300 ships and 20,000 men were lost. Mardonius thus ordered the remnants of his troop to return to the Asian side of the Aegean.[25]

Datis and Artaphernes' Campaign

Siege of Eretria

In 490 BC Datis and Artaphernes gathered another Persian expeditionary force in Cilicia with the intention to go to Attica and Eretria (the only sizable city on the island of Euboea) to punish them for their assistance to the Ionians.

The Persian force sailed from Cilicia to Rhodes, where a Lindian Temple Chronicle[26] records that Datis besieged the city of Lindos, but was unsuccessful. The fleet then moved north along the Ionian coast to Samos and thence to Naxos, where the inhabitants fled to the mountains, spread across the Cyclades, and submitted to the Great King, and then to Eretria. Eretria was besieged and surrendered after only six days; the city was razed, and temples and shrines were looted.[27]

Battle of Marathon

On the advice of Hippias, son of the former tyrant of Athens Peisistratus, the Persian army landed in Attica near Marathon.[28] Modern sources estimate they were between 20,000 and 60,000 strong.

Pheidippides, a professional messenger, was sent by the Athenians to Sparta for aid but the Spartans were prevented from leaving the city, either because of a religious festival (the Karneia[29]) or because of a helot revolt mentioned by Plato.[30] Thus the only ally the Athenians had in the Battle of Marathon were the Plataeans, with whom Athens had formed an alliance since the late sixth century BC.[31]

Miltiades, the Greek commander, marched his army of about 10,000 to Marathon to meet the invading force. After a period of about five days, the delay of which was probably beneficial to the Greeks as they had access to better supplies while the Persians supplies were being depleted as time went by, Miltiades ordered his forces to attack at a run. The rapid advance prevented the Persian archers taking position and loosing their arrows from afar. Miltiades knew that in hand to hand combat the Greek hoplite was superior. In spite of the rapid advance, the centre of the Greek formation maintained formation. When the Persian centre counterattacked, the Greeks retreated in order. The Greek wings then closed in. They were able to defeat their opposites and join force behind the Persian centre, encircling it. A great slaughter followed.[32] 6400 dead Persian bodies were counted on the battlefield and buried against only 192 Athenian[33] and 10 Plataean dead.[34]

Legend has it that Pheidippides, having returned from Sparta, was sent as a messenger from Marathon to Athens after the battle to tell them the Athenians had been victorious. He cried "Νενικήκαμεν!" (We have been victorious!), then collapsed and died on the spot. This legend was the inspiration for the modern day Olympic event, the marathon.

After the battle the Persian commanders had been given a signal of a raised shield and, hoping to catch Athens undefended, sailed with their fleet around Cape Sounion and tried to land at Phaleron. Athenian leaders had also seen the signal and, after leaving two tribes to guard the battlefield quickly moved the remaining forces into Athens. When the Persians came to Phaleron they found the Athenian army waiting for them. After this, the Persian fleet picked up the Eretrian prisoners and sailed back to Asia.[35]

The Significance of Marathon

The effects of the battle of Marathon were dramatic for both sides of the conflict. The Athenians had proven their ability to fight and win against the Persian forces, which was indeed no small feat if Herodotus's words are to be accepted. As Cornelius Nepos said:

Than this battle there has hitherto been none more glorious; for never did so small a band overthrow so numerous a host (Miltiades chapter IV, Translated by the Rev. John Selby Watson, MA)

The Greeks saw that they had the option to stand and fight, and soon after Marathon a number of city-states renounced their submission to Persia and joined with the Athenians and Spartans.

Perhaps more important was the impact Marathon had upon the Persians. Marathon was the first defeat of regular Persian infantry forces since before the reign of Cyrus, over two generations before. While the Ionian rebellion, the Persian inadequacy at sea, and the burning of Sardis all constituted a threat to Persian holdings in the region, Marathon signaled a threat to the whole of the Western part of the empire. While the Persians had been unable to beat the Ionians at sea, the conflict had been settled by the superior Persian ground forces. Now, with the defeat of the regular Persian infantry, the Persians had found themselves bested on land and sea by the relatively small city-state of Athens.

Interbellum (490-480 BC)

Persian Empire

After the defeat at Marathon, Darius ordered all the cities of his vast empire to provide warriors, ships, horses, and provisions to raise a great army for a second invasion but before he was ready to attack (in 486 BC) an insurrection broke out in Egypt, forcing a delay. In the next year Darius died after a reign of thirty-six years. His only failures in his life was that he could not defeat Scythia or capture Greece, although the tyrant of Athens had sent earth and water to Persia in 507 BC when faced with Spartan aggression. His son and successor Xerxes I was at first preoccupied with suppressing the revolt in Egypt and a later one in Babylon before he could turn his attention westward to the European side of the Aegean. It wasn't until 480 BC that the expedition was ready to proceed. Like his father's, his only failure was that he could not capture Greece, having chosen not to fight Scythia.

The Persians had the sympathy of a number of Greek city-states,[36] including Argos, which had pledged to defect when the Persians reached their borders.[37] The Aleuades family that ruled Larissa in Thessaly saw the invasion as an opportunity to extend their power.[38] Thebes was willing to pass to the Persian side when Xerxes' army reached their borders, and did so immediately following Thermopylae, though Herodotus hints that at Thermopylae it was already well known that Thebes had capitulated.

Greek City States

Meanwhile Alexander I of Macedon, who had supported the Greeks during the Ionian revolt, had been forced to submit to Persia after the Mardonius' campaign. He was sympathetic to the Hellenic side, however, and sent valuable information to the Greeks regarding Xerxes' plans and movements.

Leonidas I assumed the throne of Sparta about 488 BC, succeeding his brother.

In Athens the hero of Marathon, Miltiades, convinced the Athenians to campaign in the Cyclades Islands in order to secure their frontier.[39] His expedition failed and he was sorely wounded. His failure prompted an outcry on his return to Athens, enabling his political rivals to exploit his fall from grace. Charged with treason, he was sentenced to death, but the sentence was commuted to a fine.[40] He died of his wound before his sentence was carried out and was buried with honor.

A new political leadership formed in Athens with Themistocles leading the democratic party and Aristides the aristocratic party. Ostracism was first exercised in 488 BC[41] leading to the exile of politicians who advocated submission to Persia.

During this time Athens was at war with Aegina.The ability of the Aeginian fleet to land unopposed at will in Attica and conduct raids led to public discontent. Themistocles convinced his fellow citizens to use the profits from the Laurion silver mines to construct a fleet.[42][43] Alarm came to Greece after the Persian preparations had advanced to the construction of the Hellespont bridges and the channel at Athos.

In autumn of 481 BC Sparta, in cooperation with Athens, called a congress in the temple of Poseidon on the isthmus of Corinth. Every Greek city-state that had not then fallen to the Persians was called except Massalia and her colonies and Cyrene. General reconciliation was preached. Athens and Aegina were publicly reconciled. Messengers were sent to the cities that had not sent emissaries.[44] The colonies of Sicily and Southern Italy were called, but reportedly refused unless the Syracusan king, Gelon, was given command, a right the Spartans refused to part with.[45] Additionally, Diodorus reports that the Persians and Carthaginians had signed a treaty to co-ordinate invasions, keeping the sizeable Sicilian and Italian reinforcements in check.[46] The only help received was one ship from Crotone, which fought in the battle of Salamis. Argos[47] and Crete[48] refused to send emissaries, and the oracle of Delphi did not take part. It continued, as it had since the beginning of the century, to issue oracles that the flood of the Persian Army would drown Greece. Corcyra promised assistance, but then rescinded the offer. They sent a fleet off the Peloponnese that simply monitored the situation.[49] For the most part, the alliance was made up of the Peloponnesian city-states, Euboea island and Attica.

Second Invasion of Greece (480-479 BC)

Persian preparations

Since this was to be a full scale invasion it required long-term planning, stock-piling and conscription. Xerxes decided that the Hellespont would be bridged to allow his army to cross to Europe, and that a canal should be dug across the isthmus of Mount Athos (rounding which headland, a Persian fleet had been destroyed in 492 BC). These were both feats of exceptional ambition, which would have been beyond any contemporary state.[50] By early 480 BC, the preparations were complete,

In 481 BC, after roughly four years of preparation, Xerxes began mustering the troops for the invasion of Europe in Asia minor. The next spring, this the army marched towards Europe, crossing the Hellespont on two pontoon bridges.[51]

Size of the Persian Forces

- For more information see Size of the Persian Forces

The numbers of troops which Xerxes mustered for the second invasion of Greece have been the subject of endless dispute. Modern scholars tend to reject as unrealistic the figures of 2.5 million given by Herodotus and other ancient sources as a result of miscalculations or exaggerations on the part of the victors. The topic has been hotly debated but the consensus revolves around the figure of 200,000.[52]

The size of the Persian fleet is also disputed, although perhaps less so. Herodotus gives a number of 1,207, which is concurred with (approximately) by other ancient authors. The numbers are (by ancient standards) consistent, and this could be interpreted that a number around 1,200 is correct. Among modern scholars some have accepted this number, although suggesting that the number must have been lower by the Battle of Salamis.[53][54][55] Other recent works on the Persian Wars reject this number, 1,207 being seen as more of a reference to the combined Greek fleet in the Iliad generally claim that the Persians could have launched no more than around 600 warships into the Aegean.[56][57][58]

Greek preparations

The Athenians had also been preparing for war with the Persians since the mid-480s BC, and in 482 BC the decision was taken to build a massive fleet of triremes that would be necessary for them to fight the Persians[59]. In 481 BC Xerxes sent ambassadors around Greece asking for earth and water, but making the very deliberate omission of Athens and Sparta.[60] Support thus began to coalesce around these two leading states and a confederate alliance of Greek city-states was formed.[61] This was remarkable for the disjointed Greek world, especially since many of the city-states in attendance were still technically at war with each other.[59]

Size of Greek forces

- For more information, see Size of Greek forces

The allies had no 'standing army', nor was there any requirement to form one; since they were fighting on home territory, they could muster armies as and when required. Different sized Allied forces thus appeared throughout the campaign.

Early 480 BC: Thrace, Macedonia and Thessaly

Having crossed into Europe in April 480 BC, the Persian army began its march to Greece, taking 3 1/2 months to travel unopposed from the Hellespont to Therme. It paused at Doriskos where it was joined by the fleet. Xerxes reorganized the troops into tactical units replacing the national formations used earlier for the march.[62]

The Allied 'congress' met again in the spring of 480 BC nd agreed to defend the narrow Vale of Tempe, on the borders of Thessaly, and thereby block Xerxes's advance.[63] However, once there, they were warned by Alexander I of Macedon that the vale could be bypassed and that the army of Xerxes was overwhelming, and the Greeks retreated. [64] Shortly afterwards, they received the news that Xerxes had crossed the Hellespont.[64] A second strategy was therefore suggested by Themistocles to the allies. The route to southern Greece (Boeotia, Attica and the Peloponnesus) would require the army of Xerxes to travel through the very narrow pass of Thermopylae. This could easily be blocked by the Greek hoplites, despite the overwhelming numbers of Persians. Furthermore, to prevent the Persians bypassing Thermopylae by sea, the Athenian and allied navies could block the straits of Artemisium. This dual strategy was adopted by the congress.[65] However, the Peloponnesian cities made fall-back plans to defend the Isthmus of Corinth should it come to it, whilst the women and children of Athens had been evacuated en masse to the Peloponnesian city of Troezen.[66]

August 480 BC: Battles of Thermopylae & Artemisium

The estimated time of arrival of Xerxes at Thermopylae coincided uncomfortably with both the truce for the Olympic games, and the Spartan festival of Carneia, during both of which warfare was considered sacreligious.[67] Nevertheless, the Spartans considered the threat so grave that they despatched their king Leonidas I with his personal bodyguard (the Hippeis) of 300 hundred men (in this case, the customary elite young men in the Hippeis were replaced by veterans who already had children).[67] Leonidas was supported by contingents from the Allied Peloponnesian cities, and other forces which the Allies picked up en route to Thermopylae.[67] The Greeks proceeded to occupy the pass, rebuilt the wall the Phocians had built at the narrowest point of the pass, and waited for Xerxes's arrival.[68]

When the Persians arrived at Thermopylae in mid-August, they initially waited for three days for the Greeks to pass. When Xerxes was eventually persuaded that the Greeks intended to contest the pass, he sent his troops to attack.[69] However, the Greek position was ideally suited to hoplite warfare, the Persian contigents being forced to attack the Phalanx head on.[70] The Greeks thus withstood two full days of battle and everything Xerxes could throw at them. However, on the second day, they were betrayed by a local resident named Ephialtes who revealed a mountain path that led behind the Greek lines to Xerxes. Aware that they were being outflanked, Leonidas dismissed the bulk of the Greek army, remaining to guard the rear with perhaps 2,000 men. On the final day of the battle, the remaining Greeks sallied forth from the wall to meet the Persians in the wider part of the pass in an attempt to slaughter as many Persians as they could, but eventually they were all killed or captured.[71]

Simultaneous with the battle at Thermopylae, a Greek naval force of 271 triremes defended the Straits of Artemisium against the Persians, thus protecting the flank of the forces at Thermopylae.[72] Here the Allied fleet held off the Persians for three days; however, on the third evening the Greeks received news of the fate of Leonidas and the Allied troops and Thermopylae. Since the Greek fleet was badly damaged, and since it no longer needed to defend the flank of Thermopylae, the Greeks retreated from Artemisium to the island of Salamis.[73]

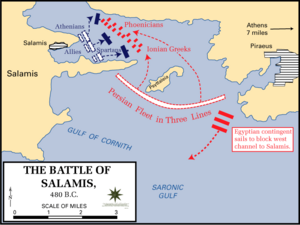

September 480 BC: Battle of Salamis

Victory at Thermopylae meant that all Boeotia fell to Xerxes; and left Attica open to invasion. The remaining population of Athens was evacuated, with the aid of the Allied fleet, to Salamis. [74] The Peloponnesian Allies began to prepare a defensive line across the Isthmus of Corinth, building a wall, and demolishing the road from Megara, thus abandoning Athens to the Persians.[75] Athens thus fell to the Persians; the small number of Athenians who had barricaded themselves on the Acropolis were eventually defeated, and Xerxes then ordered Athens to be torched.[76]

The Persians had now captured most of Greece, but Xerxes had perhaps not expected such defiance; his priority was now to complete the war as quickly as possible [77] If Xerxes could destroy the Allied navy, he would be in a strong position to force a Greek surrender;[78] Conversely by avoiding destruction, or as Themistocles hoped, by destroying the Persian fleet, the Greeks could prevent the completion of the conquest. The Allied fleet thus remained off the coast of Salamis into September, despite the imminent arrival of the Persians. Even after Athens fell, the Allied fleet still remained off the coast of Salamis, trying to lure the Persian fleet to battle.[79] Partly as a result of subterfuge on the part of Themistocles, the navies met in the cramped Straits of Salamis.[80] There, the Persian numbers were an active hindrance, as ships struggled to manoeuvre and became disorganised.[81] Seizing the opportunity, the Greek fleet attacked, and scored a decisive victory, sinking or capturing at least 200 Persian ships, and thus securing the Peloponnessus.[82]

According to Herodotus, Xerxes attempted to build a causeway across the channel to attack the Athenian evacuees on Salamis, after the loss of the battle but this project was soon abandoned. With the Persians' naval superiority removed, Xerxes feared that the Greeks might sail to the Hellespont and destroy the pontoon bridges.[83] His general Mardonius volunteered to remain in Greece and complete the conquest with a hand-picked group of troops, whilst Xerxes retreated to Asia with the bulk of the army.[84] Mardonius over-wintered in Boeotia and Thessaly; the Athenians were thus able to return to their burnt city for the winter.[77]

June 479 BC: Battles of Plataea and Mycale

Over the winter, there seems to have been some tension between the Allies. In particular, the Athenians, who were not protected by the Isthmus, but whose fleet were the key to the security of the Peloponnesus, felt hard done by, and refused to join the Allied navy in Spring.[85] Mardonius remained in Thessaly, knowing an attack on the Isthmus was pointless, whilst the Allies refused to send an army outside the Peloponessus.[85] Mardonius moved to break the stalemate, by offering peace to the Athenians using Alexander I of Macedon as intermediate.[86] The Athenians made sure that a Spartan delegation was on hand to hear the offer, but rejected it.[86] Athens was thus evacuated again, and the Persians marched south and re-took possession of it. Mardonius now repeated his offer of peace to the Athenian refugees on Salamis. Athens, along with Megara and Plataea sent emissaries to Sparta demanding assistance, and threatening to accept the Persian terms if not.[87] The Spartans thus assembled a huge Allied army and marched to meet the Persians.[88]

When Mardonius heard the Greek army was on the march, he retreated into Boeotia, near Plataea, trying to draw the Greeks into open terrain where he could use his cavalry.[89] The Greek army however, under the command of the regent Pausanias, stayed on high ground above Plataea to protect themselves against such tactics.[90] After several days of maneuver and stalemate, Pausanias ordered a night-time retreat towards their original positions.[90] This, however, went awry, leaving the Athenians, and Spartans and Tegeans isolated on separate hills, with the other contingents scattered further away near Plataea.[90] Seeing that the Persians might never have a better opportunity to attack, Mardonius ordered his whole army forward.[91] However, the Persian infantry proved no match for the heavily armoured Greek hoplites,[92] and the Spartans broke through to Mardonius's bodyguard and killed him.[93] The Persian force thus dissolved in rout; 40,000 troops managed to escape via the road to Thessaly,[94] but the rest fled to the Persian camp where they were trapped and slaughtered by the Greeks, thus finalising the Greek victory.[95][96]

On the afternoon of the Battle of Plataea, Herodotus tells us that rumour of the Greek victory reached the Allied navy, at that time off the coast of Mount Mycale in Ionia.[97] Their morale boosted, the Allied marines fought and won a decisive victory at the Battle of Mycale the same day, destroying the remnants of the Persian fleet, crippling Xerxes' sea power, and marking the ascendancy of the Greek fleet.[98]

The Greek Counterattack

Seige of Sestos

After the victory at Mycale, the Allied fleet sailed to the Hellespont to break down the pontoon bridges, but found that this was already done.[99] The Peloponnesians sailed home, but the Athenians remained to attack the Chersonesos, still held by the Persians.[99] The Persians in the region, and their allies made for Sestos, the strongest town in the region, and the Athenians laid siege to them there. After a protracted seige, Sestos fell to the Athenians, marking the beginning of a new phase in the Greco-Persian Wars, the Greek reconquest. This is where Herodotus ends his Historia.

The Unification of Macedonia

Alexander of Macedon, encouraged by the Greek success at Plataea and his victory over the Persians in the Strymon river, expanded his realm to include the other Greek tribes living east of Mount Pindus. He conquered the land east until the banks of the Strymon river, conquering several non-Greek tribes living there.[100] He founded three cities to expand Greek influence into his newly conquered land, and managed to expand his realm east of the Strymon river, gaining part of Mount Pangaion and its famous gold mines. Thus he created the largest individual Greek state in terms of area, population, and income. However, despite its potential, the kingdom of Macedon retained a splintered and feudal style of government, with the king holding little central authority and subservient to the combined force of the aristocracy. Only in the 4th century BC, when the city-states in its south were in general decline, would Phillip II of Macedon, a king with great political genius, firmly unite the Macedonian aristocracy into a strong, centralized monarchy and expand the kingdom beyond these borders and raise it to prominence.

The last Allied operation: Siege of Byzantium (478 BC)

Encouraged by Xerxes' failures, the Greeks of Asia Minor and the Cyclades revolted again. In 478 BC, a fleet composed of 20 Peloponnesian ships, 30 Athenian ships under Aristides, and other allied forces, with the general command given to Pausanias, sailed to Cyprus. There they succeeded in liberating the Greek cities, but did not succeed in their sieges against the Phoenician cities. Thus Cyprus remained a base of the Persian fleet. The Greek fleet then sailed to Byzantium.[101] Control of the Hellespont and Bosporus was of vital importance to Athens, since throughout the classical age Athens produced only 40% of the food required to feed her population, the rest being imported from the Greek colonies of the Black Sea.

The city of Byzantium fell after a siege. Many Persians including nobility fell prisoner to the Greek forces. Pausanias, who was of the royal house of Agis, was greatly impressed by the new way of life he witnessed and adopted it. He started wearing Persian dress and offering Persian-style banquets. He also mistreated the Ionian delegates. His Persian-style behaviour scandalised both the Ionians and the Peloponnesians and Pausanias was recalled to Sparta. There he faced charges that he was plotting with the Persian king to become tyrant of Greece, that he was in secret communication with him and that he had asked his daughter as his wife. He was acquitted of those charges, found guilty only of mistreating individuals in their private affairs and sentenced not to lead another campaign outside Sparta.[102] Being impatient he took a warship from Hermion and travelled back to Byzantium. No longer welcome there, he crossed the Propontis to the Troas region where he stayed for some time.[103] What he did there is completely unknown. He was recalled to Sparta by special envoy where he was to be brought against charges that he was again plotting with the King of Kings and that he was planning a helot revolution. On his way back, while he was inside the Spartan state limits, he saw the ephoroi, the elected council of five that ruled Sparta, approaching and one of them signalled to him that he was doomed. He took refuge in a nearby temple, where he died of starvation several days later. Some modern historians,[104] based on that he was never condemned and that had he been in league with the Persians he would have sought refuge there and not return, claim this was all a fabrication by his political enemies in Sparta.

In the meantime, in 477 BC the Spartans had sent Dorkis as general in Byzantium with a small force. The Ionians, with the memories of Pausanias's mistreatment of them fresh, asked them to leave. Relieved, the Spartans who no longer wished to continue fighting the Persians withdrew.[105] Athens gladly filled the vacuum, forming the First Athenian Alliance, better known as the Delian League.

The Delian League

Aristides, as leader of the Athenians, had made a very good impression on the Ionians with his character. Also, since Athenians were also Ionians, they were more trusted than the Dorian Spartans. A congress was called in the holy island of Delos where the alliance was formed. The members were given a choice of either offering armed forces or paying a tax on the joint treasury. Most cities chose the tax.[106] Aristides spent the rest of his life occupied in the affairs of the alliance, dying (according to Plutarch) a few years later in Pontus determining what the tax of new members was to be.[107]

Themistocles was marginalised politically when the leadership of the aristocratic party passed from Aristides to Cimon, son of Miltiades. Themistocles was later exiled and eventually charged of conspiring with Pausanias against Greece. After a long journey he eventually presented himself to the Persians and, following an old Persian tradition of giving sanctuary to prominent Greek politicians, he was given three cities in Asia Minor to rule. He died there a few years later.[108]

Campaigns in Thrace (476-465 BC)

Siege of Eion

Cimon, in 476 BC, began a campaign against Eion (or Heion), which still had a Persian guard. The city fell after he diverted the flow of the Strymon river and the walls collapsed. With Persians out of Eion, many Greek colonies of the Thracian coast joined the Delian League.[109]

Finally, in 465 BC, with four triremes Cimon removed the last Persians from the Thracian peninsula; thus ended Persian presence in Europe.

Campaigns in the Aegean & Pamphylia (475-462 BC)

In the intervening years, Cimon had forced Karystos in Euboea to join the league, conquered Skyros and sent Athenian colonists there, and suppressed Naxos's desertion in 468 BC.[110]

Battle of the Eurymedon

In 468 BC Cimon had gathered a force of 200 improved Athenian triremes in Knidos and 100 allied triremes with 5,000 Athenian hoplites and campaigned in Phaselis in Pamphylia. With mediation from Chios (a League member), Phasilis joined the league.

The Persian forces that had been gathered at the mouth of the Eurymedon river were defeated and the cities of Ionia officially joined the alliance.[111]

Siege of Thassos

In 465 BC Athens founded the colony of Amphipolis in the Strymon river. Thassos, a member of the League, saw her interests in the mines of Mt. Paggaion threatened and defected from the League. She called to Sparta for assistance but was denied, as Sparta was facing the largest helot revolution in its history (see the Messenian Wars).[112] An aftermath of the war was that Kimon was ostracised and the relations between Athens and Sparta turned into hostility. After a three year siege, Thassos was recaptured and forced back into the League. The siege of Thassos marks the transformation of the Delian league from an alliance into, in the words of Thucydides, a hegemony.[113]

Campaign in Egypt (462-454 BC)

In 462 BC Egypt rose again against Persia. Their king Inaros asked in 460 BC Athens for assistance which was gladly rendered because Athens wished to colonise Egypt. The Persians had gathered a force of 400,000 (according to Ctesias and Diodorus)[114] to suppress the revolution. A force of 200 Athenian triremes that was campaigning in Cyprus was immediately ordered for assistance.[115]

Battle of Pampremis

A battle took place on Pampremis in the west bank of the Nile river.[116] According to Diodorus who is our only source about Athenian engagement in this battle, the Athenian phalanx again defeated the numerically superior but individually inferior Persian archer.[117] The Egyptians and Libyans that were previously retreating on the rest of the front followed the breach in the Persian ranks the Athenians caused and won the battle.

Battles of Memphis

The Persian army retreated to Memphis.[118] A sea battle took place near there, where 40 Athenian under Charitimedes and 15 Samian ships (of the 200 that had arrived) sunk 30 and captured 20 Persian ships, according to Ctesias.[119] Between 459 BC and 456 BC the Egyptians and their Athenian allies were still engaged in the siege of the Persian force in Memphis. A large part of the Athenian fleet had been recalled to the Aegean to help with operations there. The Persians organised another force that, according to Ctesias, numbered 200,000 soldiers and 300 ships, though according to Diodorus had over 300,000 infantry and cavalry. It was led by Megabyzus. A new battle took place near Memphis. Charitimedes was killed, king Inaros escaped to the naval base that had been set up in Prosoptis island on the Nile Delta.

Siege of Prosoptis

There, assisted by 6,000 Athenians and their fleet he was besieged for 18 months. The Persian generals did not dare land. They drained the land between the river bank and the island and surprised the Egyptians. The Egyptians quickly surrendered except king Inaros. The Athenians were left alone.[120] Megabyzus negotiated with the Athenians their surrender and were allowed through Cyrene to return to their home. A number of them though was kept prisoner according to Ctesias. Athenians and their allies lost some 20,000 men in this campaign if Isocrates' numbers are accepted.[121]

War in Greece

In the mean time Athens was engaged in war in the Greek peninsula. While the helot revolution was in its final stages and Kimon in Athens, Argos rose against Sparta. The small force that was sent to quell this was defeated by a joint Athenian and Argos force in Oenoe in 460 BC. The war was generalised, and the allies of Plataea found themselves 19 years later at each other's throat. Several battles followed, the most important of which was in Tanagra.[122] Using the insecurity of the Aegean as a pretext Athens moved the joint Treasury and the seat of the alliance to Athens in 454 BC/453 BC. The war in Greece was halted in 453 BC when Kimon was recalled from exile and negotiated a five year peace with the Spartans.[123]

Campaigns in Cyprus (466-450 BC)

Ever since the battle of Eurymedon in 466 BC Athens was engaged in operations against the Persian forces in Cyprus. The task force which became engaged in the Egyptian campaign had originally been campaigning in Cyprus. A further fleet was sent from cyprus to relieve the force at Prosoptis, unaware that the Athenians there had surrendered, and was then defeated by the Persians near Cape Mendesium. The result of this loss was that Cyprus fell again to the Persians.[124]

Kimon after his recall and the five year peace was sent in Cyprus and Cilicia to fight the Persians. The Persians had helped several cities in Ionia that had tried to defect from the league.[125] With Kimon in Cyprus was sent a force of 200 triremes.[126] They were facing a force of 300 Persian ships in Cyprus led by Artabazus and 300,000 soldiers in Cilicia led by Megabyzus.

Siege of Citium

Kimon conquered Marion, but was unsuccessful in his siege of a Persian stronghold at Citium in Cyprus. He sent 60 ships to Egypt. During that siege of Citium he died of a wound or disease.[127] On his deathbed he ordered his army to lift the siege and retreat towards Salamis.

Battle of Salamis in Cyprus (450 BC)

His death was kept a secret from the Athenian army and their allies, until 30 days later the Athenians defeated both at land and sea the Persians. According to Thucydides both battles took place in Salamis.[128] According to Diodorus though the land battle took place in Cilicia where the defeated fleet had fled.[129] Thus Kimon, even after his death, defeated the Persians.

The Peace of Callias

After this battle both enemies were exhausted. None of the sides were in full control of the whole of the Eastern Mediterranean. The king of Persia sent emissaries to Athens. Pericles responded favourably and, in the autumn of 449 BC according to Diodorus, sent Callias son of Ipponicus in Susa to negotiate. The exact nature of the agreement that became known as the peace of Callias remains unclear (formal treaty or non-aggression pact). According to Diodorus it was an "important treaty", Thucydides doesn't even mention it. The terms, according to Diodorus were:[130]

- All Greek cities of Asia were to be autonomous

- Persian satraps were not to reach closer than three days walk from the sea

- No Persian warship was to be in the area between Phaselis in Pamphylia and the Bosporus

- If the Great king and his generals were to comply the Athenians were not to campaign against Artaxerxes

After the peace was agreed Athenians recalled the 60 triremes from Egypt and their forces from Cyprus (apparently this was part of the agreement though it is not mentioned) and ceased operations in this front. The situation in Greece though had flared up and war continued there until the Thirty Year Peace of 445 BC. Afterwards Greece entered in what is called the Greek Golden Age, a time of security and development.

Later Conflicts

The Persians and Greeks continued to meddle in each others' affairs. The Persians entered the Peloponnesian War in 411 BC forming a mutual-defence pact with Sparta and combining their naval resources against Athens (see Tissaphernes) in exchange for sole Persian control of Ionia. In 404 BC when Cyrus the Younger attempted to seize the Persian throne, he recruited 13,000 Greek mercenaries from all over the Greek world of which Sparta sent 700-800, believing they were following the terms of the treaty and unaware of the army's true purpose. After the failure of Cyrus, Persia tried to regain control of the Ionian city-states. The Ionians refused to capitulate and called upon Sparta for assistance, which she provided. Athens sided with the Persians, setting off the Corinthian War (see Artaxerxes II). Sparta was eventually forced to abandon Ionia and Persian authority was restored with the peace of Antalcidas. No other Greek force challenged Persia for nearly 60 years until Phillip II of Macedon, who, in 338 BC formed an alliance called οι Ελληνες (the Greeks), modelled after the alliance of 481 BC, and set in motion an invasion of the western part of Asia Minor. He was murdered before he could carry out his plan. His son, Alexander III of Macedon, known as Alexander the Great, set out in 334 BC with 38,000 soldiers. Within three years his army had conquered the Persian Empire and brought the Achaemenid dynasty to an end, bringing Greek culture up to the banks of the Indus river.

See also

References

- ↑ Herodotus book VII,89-95

- ↑ The Timetables of History by Bernard Grun. New Third Revised Edition. ISBN 067174271X

- ↑ Herodotus I,6

- ↑ Herodotus IX,121

- ↑ De legibus I,5

- ↑ Herodotus I,22

- ↑ Herodotus I,74

- ↑ Herodotus I,26-27

- ↑ Herodotus I,127

- ↑ Herodotus I,53

- ↑ Herodotus I,84

- ↑ Herodotus I,141

- ↑ Herodotus I,178

- ↑ Herodotus III,17

- ↑ Herodotus III,45

- ↑ Herodotus III,4

- ↑ Herodotus III,17

- ↑ Herodotus VI,21

- ↑ Herodotus VI 31-33

- ↑ Herodotus VI 20-22

- ↑ Herodotus VI 42-45

- ↑ Herodotus VI,49

- ↑ Herodotus VI,43,44

- ↑ Herodotus VI 45

- ↑ Herodotus VI,44

- ↑ Lind. Chron. D 1-59 in C. Higbie (2003)

- ↑ Herodotus VI,95-101

- ↑ Herodotus VI,102

- ↑ Herodotus VI,105

- ↑ Laws III 6923 D, 698 E

- ↑ Herodotus VI,108

- ↑ Herodotus VI,114

- ↑ Herodotus VI,117

- ↑ "Dr. J's Illustrated Persian Wars".

- ↑ Herodotus VI,115-116

- ↑ Herodotus VII,138

- ↑ Herodotus VII,149-152

- ↑ Herodotus VII,6

- ↑ Herodotus VI,132

- ↑ Cornelius Nepos, Miltiades VII

- ↑ Aristotle, Athenian Constitution 22.4

- ↑ Plutarch, Themistocles 4

- ↑ Cornelius Nepos, Themistocles II

- ↑ Herodotus VII,145

- ↑ Herodotus VII,158

- ↑ Diodorus 11.1.4

- ↑ Herodotus VII,149

- ↑ Herodotus VII,169

- ↑ Herodotus VII,168

- ↑ Holland, pp213-214

- ↑ Herodotus VII, 35

- ↑ de Souza, Philip (2003). The Greek and Persian Wars, 499-386 BC. Osprey Publishing. pp. page 41. ISBN 1-84176-358-6.

- ↑ Köster, A.J. Studien zur Geschichte des Antikes Seewesens. Klio Belheft 32 (1934)

- ↑ Οι δυνάμεις των Ελλήνων και των Περσών (The forces of the Greeks and the Persians), E Istorika no.164 19/10/2002

- ↑ Holland, p320

- ↑ Green, Peter, The Greco-Persian Wars. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. 1996

- ↑ Burn, A.R., "Persia and the Greeks" in The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 2: The Median and Achaemenid Periods, Ilya Gershevitch, ed. New York: Cambridge University Press. 1985.

- ↑ Briant, Pierre, From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire, Peter Daniels, trans. Indiana: Eisenbrauns. 2002

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Persian Fire. Holland, T. Abacus, ISBN 978-0-349-11717-1

- ↑ Herodotus VII, 32

- ↑ Herodotus VII, 145

- ↑ Herodotus VII, 100

- ↑ Holland, 248-249

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Herodotus VII, 173

- ↑ Holland pp255-257

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 40

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 67.2 Holland, pp257-259

- ↑ Holland, pp262-264

- ↑ Herodotus VII, 210

- ↑ Holland, p274

- ↑ Herodotus VII, 223

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 2

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 21

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 41

- ↑ Holland, p300

- ↑ Holland, pp305-306

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Holland, pp327-329

- ↑ Holland, pp308-309

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 63

- ↑ Holland, pp310-315

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 89

- ↑ Holland, pp320-326

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 97

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 100

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 Holland, pp333-335

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 Holland, pp336-338

- ↑ Herodotus IX, 7

- ↑ Herodotus IX, 10

- ↑ Holland, p339

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 90.2 Holland, pp342-349

- ↑ Herodotus IX, 59

- ↑ Herodotus IX, 62

- ↑ Herodotus IX, 63

- ↑ Herodotus IX, 66

- ↑ Herodotus IX, 65

- ↑ Holland, pp350-355

- ↑ Herodotus IX, 100

- ↑ Holland, pp357-358

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 Herodotus IX, 114

- ↑ Thucydides 2,99

- ↑ Thucydides 1.94

- ↑ Thucydides 1.95

- ↑ Thucydides I,128

- ↑ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους = History of the Greek nation volume Γ1, Athens 1972

- ↑ Thucydides 1.95

- ↑ Thucydides 1.96

- ↑ Plutarch Aristeides 26

- ↑ Plutarch Themistocles 32

- ↑ Thucydides I, 98

- ↑ Thucydides I.98

- ↑ Plutarch, Kimon 12

- ↑ Thucydides I,100

- ↑ Thucydides 101

- ↑ Diodorus 11.75

- ↑ Thucydides I.104

- ↑ Herodotus III, 12

- ↑ Diodorus XI, 74

- ↑ Diodorus 11.74

- ↑ Photius's excerpt of Ctesias, 31

- ↑ Thucydides I,109

- ↑ Isocrates, On the Peace,85

- ↑ Thucydides I.108

- ↑ Plutarch Kimon 18

- ↑ Thucydides I.110

- ↑ Thucydides I.115

- ↑ Plutarch Kimon 18

- ↑ Plutarch Kimon 19

- ↑ Thucydides I.112

- ↑ Diodorus 12.3

- ↑ Diodorus 12.4

Bibliography

- Herodotus, Ιστορίης Απόδειξη (The Histories)

- Thucydides, Ξυγκραφη (The Peloponnesian War or History of the Peloponnesian War)

- Xenophon, Κυρου Ανάβασις (Anabasis)

- Plutarch, Βίοι Παράλληλοι (Parallel lives), Themistocles, Aristides, Pericles

- Diodorus Siculus, Ιστορικη Βιβλιοθήκη (Library)

- Cornelius Nepos, Biographies, Miltiades, Themistocles

- Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους (History of the Greek Nation) volumes Β (1971) and Γ1 (1972),Ekdotiki Athinon, Athens

- Bengston, Hermann, ed., The Greeks and the Persians: From the Sixth to the Fourth Centuries. New York: Delacorte Press. 1965

- Briant, Pierre, From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire, Peter Daniels, trans. Indiana: Eisenbrauns. 2002

- Burn, A.R., "Persia and the Greeks" in The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 2: The Median and Achaemenid Periods, Ilya Gershevitch, ed. New York: Cambridge University Press. 1985.

- Cook, J.M., The Persian Empire. New York: Shocken Books. 1983.

- Green, Peter, The Greco-Persian Wars. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. 1996

- Holland, Tom (2006). Persian Fire: The First World Empire and the Battle for the West. ISBN 0385513119.

- Hignett, C., Xerxes' Invasion of Greece. Oxford: The Calrendon Press. 1963.

- Olmstead, A.T., History of the Persian Empire. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1948.

- Pomeroy, Sarah B., Stanley Burstein, Walter Donlan, and Jennifer Tolbert Roberts, Ancient Greece: A Political, Social, and Cultural History'. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1999.

- Brown Reference ltd, Atlas of World History Sandcastle books Ltd. 2006.

- Gore Vidal, Creation (novel), a sardonic view of the wars from a fictional Persian's perspective.

External links

- The Persian Wars at History of Iran on Iran Chamber Society

- Article in Greek about Salamis, includes Marathon and Xerxes' campaign

- EDSITEment Lesson 300 Spartans at the Battle of Thermopylae: Herodotus’ Real History

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||