Great Barrier Reef

| The Great Barrier Reef* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|

|

| State Party | |

| Type | Natural |

| Criteria | vii, viii, ix, x |

| Reference | 154 |

| Region** | Asia-Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1981 (5th Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. |

|

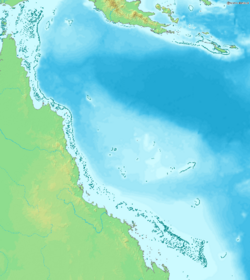

The Great Barrier Reef is the largest coral reef system in the world,[1][2] composed of over 2,900 individual reefs[3] and 900 islands stretching for 2,600 kilometres (1,600 mi) over an area of approximately 344,400 square kilometres (133,000 sq mi).[4][5] The reef is located in the Coral Sea, off the coast of Queensland in northeast Australia.

The Great Barrier Reef can be seen from outer space and is the world's biggest single structure made by living organisms.[6] This reef structure is composed of and built by billions of tiny organisms, known as coral polyps.[7] The Great Barrier Reef supports a wide diversity of life, and was selected as a World Heritage Site in 1981.[1][2] CNN has labelled it one of the 7 natural wonders of the world.[8] The Queensland National Trust has named it a state icon of Queensland.[9]

A large part of the reef is protected by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, which helps to limit the impact of human use, such as overfishing and tourism. Other environmental pressures to the reef and its ecosystem include water quality from runoff, climate change accompanied by mass coral bleaching, and cyclic outbreaks of the crown-of-thorns starfish.

Contents |

Physiography

The Great Barrier Reef is a distinct physiographic province of the larger East Australian Cordillera division. It encompasses the smaller Murray Islands physiographic section.[10]

Geology and geography

Australia has moved northwards at a rate of 7 cm (2.8 in) per year, starting during the Cainozoic.[11] Eastern Australia experienced a period of tectonic uplift, leading to the drainage divide in Queensland moving 400 km (250 mi) inland. Also during this time, Queensland experienced volcanic eruptions leading to central and shield volcanoes and basalt flows.[12] Some of these granitic outcrops have become high islands.[13] After the Coral Sea Basin was formed, coral reefs began to grow in the Basin, but until about 25 million years ago, northern Queensland was still in temperate waters south of the tropics - too cool to support coral growth.[14] The history of the development of the Great Barrier Reef is complex; after Queensland drifted into tropical waters, the history is largely influenced by how reefs fluctuate (grow and recede) as the sea level changes.[15] They can increase in diameter from 1 to 3 centimetres (0.39 to 1.2 in) per year, and grow vertically anywhere from 1 to 25 centimetres (0.4–12 in) per year; however, they are limited to growing above a depth of 150 metres (490 ft) due to their need for sunlight, and cannot grow above sea level.[16] The land that formed the substrate of the current Great Barrier Reef was a coastal plain formed from the eroded sediments of the Great Dividing Range with some larger hills (some of which were themselves remnants of older reefs[17] or volcanoes[13]).[11] When Queensland moved into tropical waters 24 million years ago, some coral grew,[18] but a sedimentation regime quickly developed with erosion of the Great Dividing Range; creating river deltas, oozes and turbidites, which would have been unsuitable conditions for coral growth. 10 million years ago, the sea level significantly lowered, which further enabled the sedimentation. The substrate of the GBR may have needed to build up from the sediment until the edge of the substrate was too far away for suspended sediments to have an inhibiting effect on coral growth. In addition, approximately 400,000 years ago there was a particularly warm interglacial period with higher sea levels and a 4 degree Celsius change in water temperature.[19]

The Reef Research Centre, a Cooperative Research Centre, has found coral 'skeleton' deposits that date back half a million years.[20] The GBRMPA considers the earliest evidence to suggest complete reef structures to have been 600,000 years ago.[21]

According to the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, the current, living reef structure is believed to have begun growing on the older platform about 20,000 years ago.[21] The Australian Institute of Marine Science agrees, which places the beginning of the growth of the current reef at the time of the Last Glacial Maximum. At around that time, the sea level was 120 metres (390 ft) lower than it is today.

From 20,000 years ago until 6,000 years ago, the sea level rose steadily. As it rose, the corals could then grow higher on the hills of the coastal plain. By around 13,000 years ago the sea level was 60 metres (200 ft) lower than the present day, and corals began to grow around the hills of the coastal plain, which were, by then, continental islands. As the sea level rose further still, most of the continental islands were submerged. The corals could then overgrow the hills, to form the present cays and reefs. Sea level on the Great Barrier Reef has not risen significantly in the last 6,000 years.[17]The CRC Reef Research Centre estimates the age of the present, living reef structure at 6,000 to 8,000 years old.[20]

The remains of an ancient barrier reef similar to the Great Barrier Reef can be found in The Kimberley, a northern region of Western Australia.[22]

The Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area has been divided into 70 bioregions,[23] of which 30 are reef bioregions,[24] and 40 are non-reef bioregions.[25] In the northern part of the Great Barrier Reef, ribbon reefs and deltaic reefs have formed; these structures are not found in the rest of the Great Barrier Reef system.[20] There are no atolls in the system,[26] and reefs attached to the mainland are rare.[11]

Fringing reefs are distributed widely, but are most common towards the southern part of the Great Barrier Reef, attached to high islands, for example, the Whitsunday Islands. Lagoonal reefs are also found in the southern Great Barrier Reef, but there are some of these found further north, off the coast of Princess Charlotte Bay. Cresentic reefs are the most common shape of reef in the middle of the Great Barrier Reef system, for example the reefs surrounding Lizard Island. Cresentic reefs are also found in the far north of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, and in the Swain Reefs (20-22 degrees South). Planar reefs are found in the northern and southern parts of the Great Barrier Reef, near Cape York, Princess Charlotte Bay, and Cairns. Most of the islands on the reef are found on planar reefs.[27]

Ecology

The Great Barrier Reef supports a diversity of life, including many vulnerable or endangered species, some of which may be endemic to the reef system.[28][29]

Thirty species of whales, dolphins, and porpoises have been recorded in the Great Barrier Reef, including the dwarf minke whale, Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin, and the humpback whale. Large populations of dugongs live there.[30][31][29]

Six species of sea turtles come to the reef to breed – the green sea turtle, leatherback sea turtle, hawksbill turtle, loggerhead sea turtle, flatback turtle, and the olive ridley. The green sea turtles on the Great Barrier Reef have two genetically distinct populations, one in the northern part of the reef and the other in the southern part.[32] Fifteen species of seagrass in beds attract the dugongs and turtles,[30] and provide a habitat for fish.[33] The most common genera of seagrasses are Halophila and Halodule.[34]

Salt water crocodiles live in mangrove and saltmarshes on the coast near the reef.[35] Nesting has not been reported, and the salt water crocodile population in the GBRWHA is wide-ranging and with a low population density.[36] Around 125 species of shark, stingray, skates or chimera live on the reef.[37][38] Close to 5,000 species of mollusc have been recorded on the reef, including the giant clam and various nudibranchs and cone snails.[30] Forty-nine species of pipefish and nine species of seahorse have been recorded.[36] At least seven species of frog can be found on the islands.[39]

215 species of birds (including 22 species of seabirds and 32 species of shorebirds) are attracted to the reef or nest or roost on the islands,[40] including the white-bellied sea eagle and roseate tern.[30] Most nesting sites are on islands in the northern and southern regions of the Great Barrier Reef, with 1.4-1.7 million birds using the sites to breed.[41][42] The islands of the Great Barrier Reef also support 2,195 known plant species; three of these are endemic. The northern islands have 300-350 plant species which tend to be woody, whereas the southern islands have 200 which tend to be herbaceous; the Whitsunday region is the most diverse, supporting 1,141 species. The plant species are spread by birds.[39]

Seventeen species of sea snake live on the Great Barrier Reef. They take three or four years to reach sexual maturity and are long-lived but with low fertility. They are usually benthic, but the species that live on the soft sediment differ from those that live on the reefs themselves. They live in warm waters up to 50 metres (164 ft) deep and are more common in the southern than in the northern part of the reef. None of the sea snakes found in the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area are endemic to the reef, nor are any of them endangered.[36]

More than 1,500 species of fish live on the reef, including the clownfish, red bass, red-throat emperor, and several species of snapper and coral trout.[30] Forty-nine species are known to mass spawn, with eighty-four other species found on the reef spawning elsewhere in their range.[43]

There are at least 330 species of ascidians found on the reef system, ranging in size from 1 mm-10 cm in diameter. Between 300-500 species of bryozoans are found on the reef system.[38]

Four hundred species of corals, both hard corals and soft corals are found on the reef.[30] The majority of these spawn gametes, breeding in mass spawning events that are controlled by the rising sea temperatures of spring and summer, the lunar cycle, and the diurnal cycle. Reefs in the inner Great Barrier Reef spawn during the week after the full moon in October, but the outer reefs spawn in November and December.[44] The common soft corals on the Great Barrier Reef belong to 36 genera.[45] Five hundred species of marine algae or seaweed live on the reef,[30] including thirteen species of the genus Halimeda, which deposit calcareous mounds up to 100 metres (110 yd) wide, creating mini-ecosystems on their surface which have been compared to rainforest cover.[46]

Environmental threats

The most significant threat to the Great Barrier Reef is climate change.[47][48] Mass coral bleaching events due to rising ocean temperatures occurred in of the summers of 1998, 2002 and 2006,[49] and coral bleaching will likely become an annual occurrence.[50] Climate change has implications for other forms of life on the Great Barrier Reef as well - some fish's preferred temperature range lead them to seek new areas to live, thus causing chick mortality in seabirds that prey on the fish. Climate change will also affect the population and available habitat of sea turtles.[51]

Another key threat faced by the Great Barrier Reef is pollution and declining water quality. The rivers of north eastern Australia provide significant pollution of the Reef during tropical flood events with over 90% of this pollution being sourced from farms.[52] Farm run-off is polluted as a result of overgrazing and excessive fertiliser and pesticide use. Due to the range of human uses made of the water catchment area adjacent to the Great Barrier Reef, water quality has declined owing to the sediment and chemical runoff from farming, and to loss of coastal wetlands which are a natural filter.[53][54][55] It is thought that the mechanism behind poor water quality affecting the reefs is due to increased light and oxygen competition from algae.[56]

The crown-of-thorns starfish is a coral reef predator which preys on coral polyps. Large outbreaks of these starfish can devastate reefs. In 2000, an outbreak contributed to a loss of 66% of live coral cover on sampled reefs in a study by the CRC Reefs Research Centre.[57] Outbreaks are believed to occur in natural cycles, exacerbated by poor water quality and overfishing of the starfish's predators.[57][58]

The unsustainable overfishing of keystone species, such as the Giant Triton, can cause disruption to food chains vital to life on the reef. Fishing also impacts the reef through increased pollution from boats, by-catch of unwanted species (such as dolphins and turtles) and reef habitat destruction from trawling, anchors and nets.[59] As of the middle of 2004, approximately one-third of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park is protected from species removal of any kind, including fishing, without written permission.[60]

Other threats to the Great Barrier Reef include shipping accidents, oil spills, and tropical cyclones.

Human use

The Great Barrier Reef has long been known to and utilised by the Aboriginal Australian and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Aboriginal Australians have been living in the area from at least 40,000 years ago,[61] and Torres Strait Islanders since about 10,000 years ago.[62] For these 70 or so clan groups, the reef is also an important part of their culture and spirituality.[63]

The reef first became known to Europeans when the HM Bark Endeavour, captained by explorer James Cook, ran aground there on June 11 1770, sustaining considerable damage. It was finally saved after lightening the ship as much as possible and re-floating it during an incoming tide.[64] One of the most famous wrecks was that of the HMS Pandora, which sank on August 29, 1791, killing 35. The Queensland Museum has been leading archaeological digs to the Pandora since 1983.[65] However, as there were no atolls on the reef system, it was largely unstudied in the 19th century.[26] During this time, some of the islands on the Great Barrier Reef were mined for deposits of guano, and lighthouses were built as beacons through the system,[66] as in Raine Island, the earliest example.[67] The Great Barrier Reef Committee was set up in 1922 which carried out much of the early research on the reef.[68]

Management

After the Royal Commissions' findings, in 1975 the Government of Australia created the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park and defined what activities were prohibited on the Great Barrier Reef.[69] The park is managed, in partnership with the Government of Queensland, through the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority to ensure that it is widely understood and used in a sustainable manner. A combination of zoning, management plans, permits, education and incentives (such as eco-tourism certification) are used in the effort to conserve the Great Barrier Reef.

In July 2004, a new zoning plan was brought into effect for the entire Marine Park, and has been widely acclaimed as a new global benchmark for the conservation of marine ecosystems.[70] The rezoning was based on the application of systematic conservation planning techniques, using the MARXAN software.[71] While protection across the Marine Park was improved, the highly protected zones increased from 4.5% to over 33.3%.[72] At the time, it was the largest marine protected area in the world, although as of 2006, the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands National Monument is the largest.[73]

In 2006, a review was undertaken of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Act 1975. Some recommendations of the review are that there should be no further zoning plan changes until 2013, and that every five years, a peer-reviewed Outlook Report should be published, examining the health of the Great Barrier Reef, the management of the reef, and environmental pressures.[5][74]

Tourism

Due to its vast biodiversity, warm clear waters and its accessibility from the floating guest facilities called 'live aboards', the reef is a very popular destination for tourists, especially scuba divers. Many cities along the Queensland coast offer daily boat trips to the reef. Several continental and coral cay islands have been turned into resorts, including the pristine resort island of Lady Elliot Island.

Domestic tourism made up most of the tourism in the region as of 1996, and the most popular visiting times were in the Australian winter. It was estimated that tourists to the Great Barrier Reef contributed $AU 776 million per annum at this time.[75]

As the largest commercial activity in the region, it was estimated in 2003 that tourism in the Great Barrier Reef generates over AU$4 billion annually.[76] (A 2005 estimate puts the figure at AU$5.1 billion.[77]) Approximately two million people visit the Great Barrier Reef each year.[78] Although most of these visits are managed in partnership with the marine tourism industry, there are some very popular areas near shore (such as Green Island) that have suffered damage due to overfishing and land based run off.

A variety of boat tours and cruises are offered, from single day trips, to longer voyages. Boat sizes range from dinghies to superyachts.[79] Glass-bottomed boats and underwater observatories are also popular, as are helicopter flights. By far, the most popular tourist activities on the Great Barrier Reef are snorkelling and diving, for which pontoons are often used, and the area is often enclosed by nets. The outer part of the Great Barrier Reef is favoured for such activities, due to water quality.

Management of tourism in the Great Barrier Reef is geared towards making tourism ecologically sustainable. A daily fee is levied that goes towards research of the Great Barrier Reef.[77] This fee ends up being 20% of the GBRMPA's income.[80] Plans of management are also in place for the popular tourist destinations of Cairns and the Whitsunday Islands, which account for 85% of the tourism in the region.[77] Policies on cruise ships, bareboat charters, and anchorages limit the traffic on the Great Barrier Reef.[77]

Fishing

The fishing industry in the Great Barrier Reef, controlled by the Queensland Government, is worth AU$1 billion annually.[81] It employs approximately 2000 people, and fishing in the Great Barrier Reef is pursued commercially, for recreation, and as a traditional means for feeding one's family.[63] Wonky holes in the reef provide particularly productive fishing areas.

See also

- Islands on the Great Barrier Reef

- Seven Natural Wonders of the World

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre (1980). "Protected Areas and World Heritage - Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area". Department of the Environment and Heritage. Retrieved on 2006-06-10.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "The Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Values". Retrieved on 2008-09-03.

- ↑ The Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area, which is 348 000 km squared, has 2900 reefs. However, this does not include the reefs found in the Torres Strait, which is estimated at an area of 37 000 km squared and with a possible 750 reefs and shoals. (Hopley et al., 2007, p.1)

- ↑ Fodor's. "Great Barrier Reef Travel Guide". Retrieved on 2006-08-08.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Department of the Environment and Heritage. "Review of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Act 1975". Retrieved on 2006-11-02.

- ↑ Sarah Belfield (2002-02-08). "Great Barrier Reef: no buried treasure". Geoscience Australia (Australian Government). Retrieved on 2007-06-11.

- ↑ Sharon Guynup (2000-09-04). "Australia's Great Barrier Reef". Science World. Retrieved on 2007-06-11.

- ↑ CNN (1997). "The Seven Natural Wonders of the World". Retrieved on 2006-08-06.

- ↑ National Trust Queensland. "Queensland Icons". Retrieved on 2006-10-17.

- ↑ Physiographic Diagram of Australia, A.K. Lobeck, by The Geological Press, Columbia University, New York, 1951. ... "to accompany text description and geological sections which were prepared by Joseph Gentilli and R.W. Fairbridge of the University of Western Australia"

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Hopley, David; Smithers, Scott G.; Parnell, Kevin E. (2007). The geomorphology of the Great Barrier Reef : development, diversity, and change. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press. p. pp.18. ISBN 0521853028.

- ↑ Hopley, David; Smithers, Scott G.; Parnell, Kevin E. (2007). The geomorphology of the Great Barrier Reef : development, diversity, and change. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press. p. pp.19. ISBN 0521853028.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Hopley, David; Smithers, Scott G.; Parnell, Kevin E. (2007). The geomorphology of the Great Barrier Reef : development, diversity, and change. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press. p. pp.26. ISBN 0521853028.

- ↑ Hopley, David; Smithers, Scott G.; Parnell, Kevin E. (2007). The geomorphology of the Great Barrier Reef : development, diversity, and change. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press. p. pp.27. ISBN 0521853028.

- ↑ Hopley, David; Smithers, Scott G.; Parnell, Kevin E. (2007). The geomorphology of the Great Barrier Reef : development, diversity, and change. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press. p. pp.27-28. ISBN 0521853028.

- ↑ MSN Encarta (2006). "Great Barrier Reef". Retrieved on 2006-12-11.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Tobin, Barry (1998, revised 2003). "How the Great Barrier Reef was formed". Australian Institute of Marine Science. Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

- ↑ Hopley, David; Smithers, Scott G.; Parnell, Kevin E. (2007). The geomorphology of the Great Barrier Reef : development, diversity, and change. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press. p. pp.29. ISBN 0521853028.

- ↑ Hopley, David; Smithers, Scott G.; Parnell, Kevin E. (2007). The geomorphology of the Great Barrier Reef : development, diversity, and change. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press. p. pp.37. ISBN 0521853028.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 CRC Reef Research Centre Ltd. "What is the Great Barrier Reef?". Retrieved on 2006-05-28.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (2006). "A "big picture" view of the Great Barrier Reef" (PDF). Reef Facts for Tour Guides. Retrieved on 2007-06-18.

- ↑ Western Australia's Department of Environment and Conservation (2007). "The Devonian 'Great Barrier Reef'". Retrieved on 2007-03-12.

- ↑ Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. "Representative Areas in the Marine Park". Retrieved on 2007-03-23.

- ↑ Great Barrier Marine Park Authority. "Protecting the Bioregions of the Great Barrier Reef".

- ↑ Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. "Bio-region Information Sheets". Retrieved on 2007-03-23.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Hopley, David; Smithers, Scott G.; Parnell, Kevin E. (2007). The geomorphology of the Great Barrier Reef : development, diversity, and change. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press. p. pp.7. ISBN 0521853028.

- ↑ Hopley, David; Smithers, Scott G.; Parnell, Kevin E. (2007). The geomorphology of the Great Barrier Reef : development, diversity, and change. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press. p. pp.158-160. ISBN 0521853028.

- ↑ CSIRO (2006). "Snapshot of life deep in the Great Barrier Reef". Retrieved on 2007-03-13.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (2000). "Fauna and Flora of the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area". Retrieved on 2006-11-24.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 30.5 30.6 CRC Reef Research Centre Ltd. "REEF FACTS: Plants and Animals on the Great Barrier Reef". Retrieved on 2006-07-14.

- ↑ Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (2004). "Environmental Status: Marine Mammals". The State of the Great Barrier Reef Report - latest updates. Retrieved on 2007-03-13.

- ↑ Dobbs, Kirstin (2007). Marine turtle and dugong habitats in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park used to implement biophysical operational principles for the Representative Areas Program. Great Barrier Marine Park Authority. http://www.gbrmpa.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/18799/rap_turtle_and_dugong_bop.pdf.

- ↑ Hopley, David; Smithers, Scott G.; Parnell, Kevin E. (2007). The geomorphology of the Great Barrier Reef : development, diversity, and change. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press. p. pp.133. ISBN 0521853028.

- ↑ Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (2005). "Environmental Status: Seagrasses". The State of the Great Barrier Reef Report - latest updates. Retrieved on 2007-05-23.

- ↑ Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (2005). "Environmental Status: Marine Reptiles".

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 "Appendix 2 - Listed Marine Species". Fauna and Flora of the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area (2000). Retrieved on 2007-05-23.

- ↑ "Environmental Status: Sharks and rays". The State of the Great Barrier Reef Report - latest updates. Retrieved on 2007-05-23.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 "Appendix 4- Other species of conservation concern". Fauna and Flora of the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area (2000). Retrieved on 2007-09-13.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 "Appendix 5- Island Flora and Fauna". Fauna and Flora of the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area (2000). Retrieved on 2007-09-13.

- ↑ Hopley, David; Smithers, Scott G.; Parnell, Kevin E. (2007). The geomorphology of the Great Barrier Reef : development, diversity, and change. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press. p. pp.450-451. ISBN 0521853028.

- ↑ Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. "Environmental status: birds". The State of the Great Barrier Reef Report - latest updates. Retrieved on 2007-05-23.

- ↑ "Environmental status: birds Condition". The State of the Great Barrier Reef Report - latest updates. Retrieved on 2007-05-23.

- ↑ Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. "Fish Spawning Aggregation Sites On The Great Barrier Reef".

- ↑ Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (2006). "Information Fact Sheets #20 Coral Spawning" (PDF). Retrieved on 2007-05-27.

- ↑ Australian Institute of Marine Science (2002). "Soft coral atlas of the Great Barrier Reef". Retrieved on 2007-05-27.

- ↑ Hopley, David; Smithers, Scott G.; Parnell, Kevin E. (2007). The geomorphology of the Great Barrier Reef : development, diversity, and change. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press. p. pp.185. ISBN 0521853028.

- ↑ Rothwell, Don; Stephens, Tim (November 19, 2004). "Global climate change, the Great Barrier Reef and our obligations". The National Forum. Retrieved on 2007-09-26.

- ↑ Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. "Our changing climate". Retrieved on 2007-09-26.

- ↑ Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. "Coral Bleaching and Mass Bleaching Events". Retrieved on 2006-05-30.

- ↑ The The Daily Telegraph - January 30, 2007 - Online version

- ↑ Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. "Climate change and the Great Barrier Reef". Retrieved on 2007-03-16.

- ↑ "Coastal water quality" (PDF). The State of the Environment Report Queensland 2003. Environment Protection Agency Queensland (2003). Retrieved on 2007-06-07.

- ↑ Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. "Wetlands". Retrieved on 2007-03-13.

- ↑ Brodie, J. (2007). "Nutrient management zones in the Great Barrier Reef Catchment: A decision system for zone selection" (PDF). Australian Centre for Tropical Freshwater Research. Retrieved on 2007-06-07.

- ↑ Australian Government Productivity Commission (2003). "Industries, Land Use and Water Quality in the Great Barrier Reef Catchment - Key Points". Retrieved on 2006-05-29.

- ↑ Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (2006). "Principal water quality influences on Great Barrier Reef ecosystems". Retrieved on 2006-10-22.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 "CRC REEF RESEARCH CENTRE TECHNICAL REPORT No. 32 — Crown-of-thorns starfish(Acanthaster planci) in the central Great Barrier Reef region. Results of fine-scale surveys conducted in 1999-2000.". Retrieved on 2007-06-07.

- ↑ CRC Reef Research Centre. "Crown-of-thorns starfish on the Great Barrier Reef". Retrieved on 2006-08-28. (PDF)

- ↑ CSIRO Marine Research (1998). "Environmental Effects of Prawn Trawling". Retrieved on 2006-05-28.

- ↑ Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. "Marine Park Zoning". Retrieved on 2006-08-08.

- ↑ Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (2006 date). "[http://www.gbrmpa.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/2142/Fact_Sheet_04_IPLU.pdf Fact Sheet No. 4 - Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People and the Great Barrier Reef. Region]". Retrieved on 2006-05-28.

- ↑ Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. "reefED - GBR Traditional Owners". Retrieved on 2006-05-28.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. "Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Culture & Dugongs and Turtles". Retrieved on 2007-05-23.

- ↑ Captain Cook's Journal During the First Voyage Round the World at Project Gutenberg

- ↑ Queensland Museum. "HMS Pandora". Retrieved on 2006-10-12.

- ↑ Hopley, David; Smithers, Scott G.; Parnell, Kevin E. (2007). The geomorphology of the Great Barrier Reef : development, diversity, and change. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press. p. pp.452. ISBN 0521853028.

- ↑ "Raine Island Corporation". Retrieved on 2007-11-20.

- ↑ Hopley, David; Smithers, Scott G.; Parnell, Kevin E. (2007). The geomorphology of the Great Barrier Reef : development, diversity, and change. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press. p. pp.9. ISBN 0521853028.

- ↑ Commonwealth of Australia (1975). "Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Act 1975". Retrieved on 2006-08-30.

- ↑ Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (2003). "Zoning Plan 2003". Retrieved on 2006-10-02. (PDF)

- ↑ Fernandes et al. (2005) Establishing representative no-take areas in the Great Barrier Reef: large-scale implementation of theory on marine protected areas, Conservation Biology, 19(6), 1733-1744.

- ↑ World Wildlife Fund Australia. "Great Barrier Reef - WWF-Australia". Retrieved on 2006-11-10.

- ↑ Bush to protect Hawaiian islands, BBC News, 15 June 2006

- ↑ "Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report". Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (2007). Retrieved on 2007-08-31.

- ↑ "Ecological Economics Criteria for Sustainable Tourism: Application to the Great Barrier Reef and Wet Tropics World Heritage Areas, Australia". Journal of Sustainable Tourism 4 (1). 1996. http://www.multilingual-matters.net/jost/004/0003/jost0040003.pdf. Retrieved on 2008-10-31.

- ↑ Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (2003). "Summary report of the social and economic impacts of the rezoning of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park.". Retrieved on 2006-10-19. (PDF)

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 77.2 77.3 Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (2005). "Protecting Biodiversity Brochure 2005". Retrieved on 2006-11-11.

- ↑ Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. "Number of Tourists Visiting The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park". Retrieved on 2006-10-12.

- ↑ Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (2005). "What You Do". Onboard - The Tourism Operator's Handbook for the Great Barrier Reef. Retrieved on 2006-11-14.

- ↑ Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (2005). "How is the Money Used?". Onboard - The Tourism Operator's Handbook for the Great Barrier Reef. Retrieved on 2006-11-11.

- ↑ Access Economics Pty Ltd (2005). "Measuring the economic and financial value of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park". Retrieved on 2007-03-16. (PDF)

Further reading

- Bell, Peter (1998). AIMS: The First Twenty-five Years. Townsville: Australian Institute of Marine Science. ISBN 9780642322128.

- Bowen, James; Bowen, Margarita (2002). The Great Barrier Reef : history, science, heritage. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521824303.

- Done, T.J. (1982). "Patterns in the distribution of coral communities across the central Great Barrier Reef". Coral Reefs 1 (2): 95–107. doi:.

- Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority Research Publications

- Lucas, P.H.C. et al. (1997). The outstanding universal value of the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area. Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. ISBN 0642230285.

- Mather, P.; Bennett, I., ed. (1993). A Coral Reef Handbook: A Guide to the Geology, Flora and Fauna of the Great Barrier Reef (3rd edition ed.). Chipping North: Surrey Beatty & Sons Pty Ltd. ISBN 0949324477.

External links

- How the Great Barrier Reef Works

- Great Barrier Reef travel guide from Wikitravel

- World heritage listing for Great Barrier Reef

- Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority

- CRC Reef Research Centre

- Biological monitoring of coral reefs of the GBR

- Great Barrier Reef (World Wildlife Fund)

- Dive into the Great Barrier Reef from National Geographic

|

|||||||