Gray Whale

| Gray Whale[1] Fossil range: Upper Pleistocene - Recent |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A Gray Whale spy-hopping

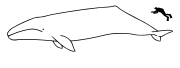

Size comparison against an average human

|

||||||||||||||||

| Conservation status | ||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Binomial name | ||||||||||||||||

| Eschrichtius robustus Lilljeborg, 1861 |

||||||||||||||||

Gray Whale range

|

The Gray (or Grey) Whale (Eschrichtius robustus) is a whale that travels between feeding and breeding grounds yearly. It reaches a length of about 16 meters (52 ft), a weight of 36 tons and an age of 50–60 years. Gray Whales were once called Devil Fish because of their fighting behavior when hunted. The Gray Whale is the sole species in the genus Eschrichtius, which in turn is the sole genus in the family Eschrichtiidae. This animal is descended from the filter-feeding whales that developed at the beginning of the Oligocene, over 30 million years before the present.

The Gray Whale is distributed in a eastern North Pacific (American) population and a critically endangered western North Pacific (Asian) population. A third population in the North Atlantic became extinct in the 18th century.

Contents |

Taxonomy

The Gray Whale has been traditionally placed in its own monotypic genus and family, however recent DNA sequencing analysis indicates that the Gray Whale is more closely related to the Humpback (Megaptera) and the Blue Whales than to the remaining rorquals of Balaenoptera. Though two populations, a north-west Pacific or Asian and north-east Pacific or American, are recognized, they are not deemed distinct enough to warrant subspecific status.

It was first described from remains found in England and Sweden, where it had become extinct long before. Initially named Balaenoptera robusta by Wilhelm Lillebjorg,[3] it was placed in its own genus by John Gray, naming it in honour of zoologist Daniel Eschricht.[4] Meanwhile the living Pacific species was described by Cope as Ranchianectes glaucus in 1869.[5] Skeletal comparisons showed the Pacific species to be identical to the Atlantic remains in the 1930s and Gray's name has been generally accepted since.[6][7]

The name Eschrichtius gibbosus is sometimes seen; this is dependent on the acceptance of a 1777 description by Erxleben.[8]

Many other names have been ascribed to the Gray Whale, including Desert Whale[9], Devil Fish, Gray Back, Mussel Digger and Rip Sack.[10]

Description

The Gray Whale is a dark slate-gray in color and covered by characteristic gray-white patterns, scars left by parasites which drop off in the cold feeding grounds. It lacks the numerous prominent furrows of the related rorquals, instead bearing two to five shallow furrows on the underside of the throat. The Gray Whale lacks a dorsal fin, instead bearing several dorsal 'knuckles'.

Whale population

Two Pacific Ocean populations of the Gray Whale exists: one of not more than 300 individuals whose migratory route is unknown, but presumed to be between the Sea of Okhotsk and southern Korea, and a larger one with a population between 20,000 and 22,000 individuals in the Eastern Pacific travelling between the waters off Alaska and the Baja California.

The Gray Whale was thought to have become extinct in the North Atlantic in the 17th century.[11] Radiocarbon dating of subfossil remains has confirmed this, with whaling the possible cause.[12]

In the fall, the Eastern Pacific, or California, Gray Whale starts a 2–3 month, 8,000–11,000 km trip south along the west coast of Canada, the United States and Mexico. The animals travel in small groups. The destinations of the whales are the coastal waters of Baja California and the southern Gulf of California, where they breed and the young are born. The breeding behavior is complex and often involves three or more animals. The gestation period is about one year, and females have calves every other year. The calf is born tail first and measures about 4 meters in length. It is believed that the shallow waters in the lagoons there protect the newborn from sharks.

After several weeks, the return trip starts. This round trip of 16,000–22,000 km, at an average speed of 5 km/h, is believed to be the longest yearly migration of any mammal. A whale watching industry provides ecotourists and marine mammal enthusiasts the opportunity to see groups of Gray Whales as they pass by on their migration.

Feeding

The whale feeds mainly on benthic crustaceans which it eats by turning on its side (usually the right) and scooping up the sediments from the sea floor. It is classified as a baleen whale and has a baleen, or whalebone, which acts like a sieve to capture small sea animals including amphipods taken in along with sand, water and other material. Mostly, the animal feeds in the northern waters during the summer; and opportunistically feeds during its migration trip, depending primarily on its extensive fat reserves.

Migration

The migration route of the Eastern Pacific, or California, Gray Whale is often described as the longest known mammal migration. Beginning in the Bering and Chukchi seas and ending in the warm-water lagoons of Mexico's Baja peninsula, their round trip journey moves them through 12,500 miles of coastline.

This journey begins each October as the northern ice pushes southward. Travelling both night and day, the Gray Whale averages approximately 120 km (80 miles) per day. By mid-December to early January, the majority of the Gray Whales are usually found between Monterey and San Diego, where they are often seen from shore.

By late December to early January, the first of the Gray Whales begin to arrive the calving lagoons of Baja. These first whales to arrive are usually pregnant mothers that look for the protection of the lagoons to give birth to their calves, along with single females seeking out male companions in order to mate. By mid-February to mid-March the bulk of the Gray Whales have arrived the lagoons. It is at this time that the lagoons are filled to capacity with nursing, calving and mating Gray Whales.

The three primary lagoons that the whales seek in Baja California are Scamnon's (named after a famous whaleman in the 1850s who discovered the lagoons and later became one of the first protectors of the Grays), San Ignacio and Magdalena. As noted, the Grays were called the devil fish until the early 1970s when a fisherman in the Laguna San Ignacio named Pachico Mayoral (although terrified to death) reached out and touched a Gray mother that kept approaching his boat. Today the whales in Laguna San Ignacio are protected but it is possible to visit a whale camp there and have the same experience that Pachico had.

Throughout February and March, the first Gray Whales to leave the lagoons are the males and single females. Once they have mated, they will begin the trek back north to their summer feeding grounds in the Bering and Chukchi seas. Pregnant females and nursing mothers with their newborn calves are the last to leave the lagoons. They leave only when their calves are ready for the journey, which is usually from late March to mid-April. Often there are still a few lingering Gray Whale mothers with their young calves in the lagoons well into May.

A population of about 2,000 Gray Whales stay along the Oregon coast throughout the summer, not making the farther trip to Alaska waters.

Conservation and human interaction

The only predators of adult Gray Whales are humans and the Orca. Beginning in the 1570s the Japanese began to catch Gray Whales. At Kawajiri, Nagato 169 Gray Whales were caught between 1698 and 1889, or a little over one a year. At Tsuro, Shikoku 201 were taken between 1849 and 1896. Several hundred more were probably caught by European (primarily American) whalemen in the Sea of Okhotsk from the 1840s to perhaps the early 20th century. A total of forty-four were caught by net whalemen in Japan during the 1890s. The real damage was done between 1911 and 1933, when Korean and Japanese whalemen killed 1,449 Gray Whales. By 1934 the western Gray Whale was near extinction. From 1891 to 1966 an estimated 1,800-2,000 Gray Whales were caught, with peak catches of 100-200 annually occurring in the 1910s.

European commercial whaling for Gray Whales in the North Pacific began in the winter of 1845-46, when two United States ships, the Hibernia and the United States, caught thirty-two in Magdalena Bay. More ships followed in the two following winters (1846-47 and 1847-48), after which gray whaling in the bay was nearly abandoned because "of the inferior quality and low price of the dark-colored gray whale oil, the low quality and quantity of whalebone from the gray, and the dangers of lagoon whaling."

Gray whaling in Magdalena Bay was revived in the winter of 1855-56 by several vessels, mainly from San Francisco, including the ship Leonore, under Captain Charles Melville Scammon. This was the first of eleven winters from 1855 through 1865 known as the "bonanza period," during which gray whaling along the coast of Baja California reached its peak. Not only were Grays taken in Magdalena Bay, but also by ships anchored along the coast from San Diego south to Cabo San Lucas and from whaling stations from Crescent City in northern California south to San Ignacio Lagoon. During the same period vessels targeting Right and Bowhead Whales in the Gulf of Alaska, Sea of Okhotsk, and the Western Arctic would occasionally take a Gray or two if neither of the former two species were in sight.

In December 1857 Charles Scammon, in the brig Boston, along with his schooner-tender Marin, entered Laguna Ojo de Liebre (Jack-Rabbit Spring Lagoon) or later known as Scammon's Lagoon (by 1860) and found one of the Gray Whale's last refuges. In three months he caught a total of forty-seven whales for a yield of 1,700 barrels of oil. In the winter of 1859-60 Scammon, in the bark Ocean Bird, along with several other vessels, performed a similar feat of daring by entering San Ignacio Lagoon to the south where he discovered the last of the Gray Whales' breeding lagoons. Within only a couple of seasons the lagoon was nearly cleaned out of whales.

Between 1846 and 1874 an estimated 8,000 Gray Whales were killed by European whalemen, with over half having been killed in the Magdalena Bay complex (Estero Santo Domingo, Magdalena Bay itself, and Almejas Bay) and by shore whalemen in California and Baja California. This, for the most part, does not take into account the large number of calves injured or left to starve after their mothers had been killed in the breeding lagoons. Since whalemen primarily targeted mothers with calves in the lagoons, several thousand should probably be added to the total. Also, shore whaling in California and Baja California continued after this period, until the early 20th century.

During the modern era a second, shorter, and less intensive hunt occurred for Gray Whales in the eastern North Pacific. Only a few were caught from two whaling stations on the coast of California from 1919 to 1926, and a single station in Washington (1911-21) accounted for the capture of another. For the entire west coast of North America for the years 1919 to 1929 some 234 Gray Whales were caught. Only a dozen or so were taken by the stations in British Columbia, nearly all of them in the 1953 season at Coal Harbor. A whaling station in Richmond, California caught 311 Gray Whales for "scientific purposes" between 1964 and 1969. From 1961 to 1972 the Soviet Union caught 138 Gray Whales, although they originally had reported not having taken any. The only other significant catch was made in two seasons by the steam-schooner California off Malibu, California. In the winters of 1934-35 and 1935-36 the California anchored off Point Dume in Paradise Cove. In all she caught at least 272 Gray Whales, with 186 of them being caught in the first winter. In 1936 Gray Whales were protected, forcing the ship to concentrate on other species.

Gray Whales have been granted protection from commercial hunting by the International Whaling Commission (IWC) since 1949, and are no longer hunted on a large scale.

Limited hunting of Gray Whales has continued since that time, however, primarily in the Chukotka region of north-eastern Russia, where large numbers of Gray Whales spend the summer months. This hunt has been allowed under an "aboriginal/subsistence whaling" exception to the commercial-hunting ban. Anti-whaling groups have protested the hunt, saying that the meat from the whales is not for traditional native consumption, but is used instead to feed animals in government-run fur farms; they cite annual catch numbers that rose dramatically during the 1940s, at the time when state-run fur farms were being established in the region. Although the Soviet government denied these charges as recently as 1987, in recent years the Russian government has acknowledged the feeding of Gray Whale meat to animals on fur farms in the region. The Russian IWC delegation has said that the hunt is justified under the aboriginal/subsistence exemption, since the fur farms provide a necessary economic base for the region's native population.

Currently, the annual quota for the Gray Whale catch in the region is 140 whales per year. Pursuant to an agreement between the United States and Russia, the Makah Indian tribe of Washington claimed 4 whales per year from the total IWC quota established at the 1997 meeting. With the exception of a single Gray Whale killed in 1999, the Makah people have been prevented from conducting Gray Whale hunts by a series of legal challenges, culminating in a United States federal appeals court decision in December 2002 that said the National Marine Fisheries Service must prepare an Environmental Impact Statement before allowing the hunt to go forward. On September 8, 2007, five members of the Makah tribe shot a gray whale using high powered rifles in spite of the limitations. The whale died within 12 hours, sinking while heading out to sea. [13]

As of 2001, the population of California Gray Whales had grown back to about 26,000 animals. As of 2004, the population of Western Pacific (seas near Korea, Japan, and Kamchatka) Gray Whales was an estimated 101 individuals.

The North Atlantic population of Gray Whales may have been hunted to extinction in the 18th century, but there is no concrete evidence to support this assertion. There is circumstantial evidence that whaling could have possibly contributed to this population's decline, as an increase in whaling activity in the 17th and 18th century did coincide with the population's disappearance.[12]

As of 2008, the IUCN regards the Gray Whale as being of "Least Concern" from a conservation perspective. However, the specific subpopulation in the northwest Pacific is regarded as being "Critically Endangered".[2]

Captivity

In 1972, a 3-month-old Gray Whale named Gigi was captured for brief study, and then released near San Diego.

In January 1997, the new-born baby whale J.J. was found helpless near the coast of Los Angeles, California, 4.2 m long and 800 kg in mass. Nursed back to health in SeaWorld San Diego, she was released into the Pacific Ocean on March 31, 1998, 9 m long and 8500 kg in mass. She shed her radio transmitter packs three days later.

In the news

A Gray Whale, thought to have got lost on its migration, was seen in the Fraser River in British Columbia, Canada on January 25, 2007. It then headed the right way back to the ocean, albeit slowly.

A lone Gray Whale was seen in early 2005 on the eastern coastline of Japan, and around Tokyo bay. It attracted crowds of whale watchers in April, but later became entangled in a fisherman's net, drowned and was washed up in early May.[14]

References

- ↑ Mead, James G. and Robert L. Brownell, Jr (November 16 2005). Wilson, D. E., and Reeder, D. M. (eds). ed.. Mammal Species of the World (3rd edition ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 723–743. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. http://www.bucknell.edu/msw3/browse.asp?id=14300030.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Reilly SB, Bannister JL, Best PB, Brown M, Brownell Jr. RL, Butterworth DS, Clapham PJ, Cooke J, Donovan GP, Urbán J & Zerbini AN (2008). Eschrichtius robustus. 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN 2008. Retrieved on 2008-10-17.

- ↑ Lilljeborg (1861). "Balaenoptera robusta". Forh. Skand. Naturf. Ottende Mode, Kopenhagen 8: 602.

- ↑ Gray (1864). "Eschrichtius". Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist. 3 (14): 350.

- ↑ Cope (1869). "Rhachianectes". Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Philadelphia 21: 15.

- ↑ Cederlund, BA (1938). "A subfossil gray whale discovered in Sweden in 1859". Zoologiska Bidrag Fran Uppsala 18: 269–286.

- ↑ Mead JG, Mitchell ED (1984). "Atlantic gray whales". in Jones ML, Swartz SL, Leatherwood S. The Gray Whale. London: Academic Press. pp. 33–53.

- ↑ Erxleben (1777). "Balaena gibbosa". Systema regni animalis: 610.

- ↑ Katherine Waser Ecotourism and the desert whale: An interview with Dr. Emily Young (1998). . Arid Lands Newsletter.

- ↑ Eschrichtius robustus (TSN 180521). Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved on March 18 2006.

- ↑ Rice DW (1998) (in English). Marine Mammals of the World. Systematics and Distribution. Special Publication Number 4.. Lawrence, Kansas: The Society for Marine Mamalogy.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Bryant, PJ (August 1995). "Dating Remains of Gray Whales from the Eastern North Atlantic". Journal of Mammalogy 76 (3): 857–861. doi:.

- ↑ Local News | Gray whale shot, killed in rogue tribal hunt | Seattle Times Newspaper

- ↑ (BBC News)

External links

- Interactive Migration Map at the PBS Ocean Adventures site

- Information on JJ from Sea World

- U.S. International Whaling Commission (IWC) delegation's press release announcing the establishment of a combined Russian-Makah Gray Whale quota (1997)

- U.S. State Department report: Russia's Chukotka Autonomous Region Overview (1998), including the following passage documenting use of marine mammal meat in Chokotkan fur farms:

- Marine Mammal Hunting. Marine mammal hunting is part of the traditional lifestyle of the indigenous population in coastal Chukotkan communities. Native peoples are provided with an annual quota to procure 169 whales, 10,000 ringed seals, and 3,000 walruses. Marine mammal by-products are used as food in fox ranches.

- IWC report on aboriginal/subsistence whaling quota for 2004

- Humane Society of the U.S. page documenting the history of the Makah whaling litigation (2003)

- Two articles from the pro-native-whaling World Council of Whalers: Chukotkan whaling: Technology, tradition and hope combine to save a people (2000), and World whaling: Russia (2004).

- Article from the Seattle Post-Intelligencer on cooperation between the Chukchi and Makah native people in their efforts to resume traditional whaling activities: Two tribes reach out across miles -- and years -- with whaling link (2004).

- Article showing people petting Gray Whales in Baja Mexico that swim up to small fishing boats: We Pet Gray Whales in Baja Mexico's San Ignacio Lagoon

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||