Gray Davis

|

Joseph Graham Davis Jr.

|

|

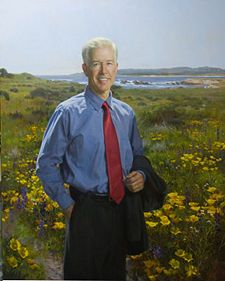

Official state portrait |

|

|

|

|

|---|---|

| In office January 4, 1999 – November 17, 2003 |

|

| Lieutenant | Cruz Bustamante |

| Preceded by | Pete Wilson |

| Succeeded by | Arnold Schwarzenegger |

|

44th Lieutenant Governor of California

|

|

| In office 1995 – 1999 |

|

| Governor | Pete Wilson |

| Preceded by | Leo T. McCarthy |

| Succeeded by | Cruz Bustamante |

|

28th California State Controller

|

|

| In office 1987 – 1995 |

|

| Preceded by | Kenneth Cory |

| Succeeded by | Kathleen Connell |

|

Member of the California State Assembly for the 43rd district

|

|

| In office 1982 – 1986 |

|

| Preceded by | Howard Berman |

| Succeeded by | Terry Friedman |

|

|

|

| Born | December 26, 1942 New York City, New York, USA |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Sharon Ryer Davis |

| Alma mater | Stanford University |

| Profession | Politician |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

| Military service | |

| Service/branch | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1968–1969[1] |

| Rank | Captain (United States) |

| Commands | Europe |

| Battles/wars | Vietnam |

| Awards | Bronze Star |

Joseph Graham “Gray” Davis, Jr. (born December 26, 1942) is an American politician who served as California's 37th Governor from 1999 to 2003. Davis is a Democrat who was often known as a moderate. Prior to serving as Governor, Davis served as Chief of Staff to Governor Jerry Brown (1975-1981), California State Assemblyman (1983-1987), California State Controller (1987-1995), and Lieutenant Governor of California (1995-1999). Davis holds a B.A. in history from Stanford University and a J.D. from Columbia Law School. He was awarded a Bronze Star for his service as a Captain in the Vietnam War.

During his time as Governor, Davis made education his top priority and California spent eight billion dollars more than was required under Proposition 98 during his first term. Under Davis, California standardized test scores increased for five straight years.[2] Davis signed the nation's first state law requiring automakers to limit auto emissions. Davis supported laws to ban assault weapons. He is also credited with improving relations between California and Mexico.[3] Davis began his tenure as Governor with strong approval ratings, but those ratings declined as voters blamed Davis for the California electricity crisis and the California budget crisis that followed the dot-com bubble burst. Voters were also alienated by Davis’s record breaking fundraising efforts and negative campaigning.[4]

On October 7, 2003, he became the second governor to be recalled in American history. Davis was succeeded by Republican Arnold A. Schwarzenegger on November 17 after the recall election. Davis spent 1,778 days as Governor, and signed 5,132 bills out of 6,244, vetoing 1,100 bills.[5] Since being recalled, Davis has worked as a guest lecturer at the UCLA School of Public Affairs and as an attorney at Loeb & Loeb, and sat on the Board of Directors of the animation company DiC Entertainment.

Contents |

Early life and political career

Born in New York City, Davis moved to California with his family as a child in 1954. He was the first of the family's five children: three boys and two girls. He was raised a Roman Catholic. Davis and his family were one of the millions of Americans to migrate to the southwest and California as part of the post World War II sun belt migration.

His education included experience at public, private and Catholic schools, allowed him – as an adult – an opportunity to compare all three systems later as a lawmaker.[6] Davis graduated from a North Hollywood military academy, the Harvard School for Boys (now part of Harvard-Westlake School). Davis's family was upper middle class and was led by his demanding mother.[6] Davis was nicknamed Gray by his mother.[7] His father was an alcoholic.[6]

His strong academic accomplishments earned him acceptance to Stanford University.[6] He played on the Stanford golf team with a two handicap.[8] After Davis entered Stanford University, his father left the family, forcing Davis to join the ROTC to stay in school. The deal included a promise to enter the regular Army after completing his education. He earned a Bachelor of Arts in history at Stanford, where he was admitted to the Zeta Psi fraternity, graduating in 1964 with distinction. He then returned to New York to attend Columbia Law School where he won the Moot Court award. During law school Davis had a romantic encounter with actress Cybil Shepherd.[9] He graduated from Columbia in 1967 and then clerked at the law firm of Beekman & Bogue in New York City.

After completing the program in 1967 he entered active duty in the United States Army, serving in the Vietnam War during its height until 1969.[1] Davis saw time on the battlefield during his time in Vietnam.[6] Davis returned home as a captain with a Bronze Star for meritorious service. Friends who knew him at the time said Davis – like many war veterans – came back a changed man, interested in politics and more intense, according to the Sacramento Bee.[1] He returned from Vietnam more "serious and directed."[6] Davis was surprised to discover that the majority of those serving in Vietnam were Latinos, African Americans, and southern whites with very few from schools like Stanford and Columbia; Davis believed that the burden of the war should be felt equally and he resolved early on to go about changing America so that would change.[10] Davis is a life member of the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars.[11]

Davis volunteered for the campaign of John V. Tunney for the United States Senate in 1970.[10] He started a statewide neighborhood crime watch program while serving as chairman of the California Council on Criminal Justice.[1] His initial political experience included working to help Tom Bradley win election as Los Angeles' first black mayor in 1973. The historical significance of Bradley's victory further inspired Davis to pursue a career in politics.[10] Davis ran for State Treasurer in 1974 but lost when the more popular Jesse Unruh filed to run on the deadline.[10]

Davis returned to California and entered politics, serving as Executive Secretary and Chief of Staff to Governor Edmund G. "Jerry" Brown Jr. from 1975 to 1981. In 1976, while Chief of Staff, Davis was suspended from the State Bar of California on the first of two occasions.[12] Davis was not as liberal as Brown, and some said he offset Brown's style by projecting a more intense, controlled personality.[1] While Brown was campaigning for President in 1980, Davis ran California in Brown's absence though Davis would later claim that we always did what he thought Brown would have done.[13]

He met his future wife, the former Sharon Ryer, while on an airplane tending to official business in 1978. Ryer, a flight attendant for Pacific Southwest Airlines, was miffed when Davis held up the departure of the flight from Sacramento to Los Angeles. Davis apologized and asked her out, and they later married in 1983, with California Supreme Court justice Rose Bird officiating.[14]

He was elected to the office of Assemblyman from the 43rd district, representing parts of Los Angeles County including West Los Angeles and Beverly Hills[15] from 1983 to 1987. Davis championed a popular campaign to help find missing children by placing their pictures on milk cartons and grocery bags.[1][16]

Prior to Governorship

State Controller

In 1986, Davis ran against six other contenders in his race for State Controller; several of those candidates, including Democrat John Garamendi and Republican Bill Campbell, were arguably better known at the time.[6] Davis served as State Controller for eight years until 1995. As California's chief fiscal officer, he saved taxpayers more than half a billion dollars by cracking down on Medi-Cal fraud, rooting out government waste and inefficiency, and exposing the misuse of public funds.[17] He was the first Controller to withhold paychecks from all state elected officials, including himself, until the Governor and the Legislature passed an overdue budget. He also found and returned more than $1.8 billion in unclaimed property to California citizens, including forgotten bank accounts, insurance settlements, and stocks.[17]

1992 campaign for Senate

Davis ran against San Francisco mayor Dianne Feinstein for the Democratic nomination for the United States Senate in the 1992 special election to fill the Senate seat vacated by Pete Wilson who was elected Governor of California in 1990. The race is often cited as an example of Davis's history of negative campaign tactics.[18] The Davis campaign featured an ad that compared Feinstein to the incarcerated hotelier Leona Helmsley.[16] Some experts consider that ad to be the most negative in state history.[19] The ad backfired with Davis losing to Feinstein by a significant margin for the nomination although this loss did not stop Davis from using negative campaign ads in the future, including in his race for Lieutenant Governor.[18] Davis blamed his campaign managers for the defeat and vowed not to let major decisions in future campaigns be decided by his campaign staff.[16] In 2003, when Feinstein urged voters to vote no during the recall election, she was constantly reminded through questions, video, and the media about the 1992 primary.[19]

Lieutenant Governor

Many Democrats came to believe that Davis's political career was over after his defeat in his run for the Senate but Davis created a new campaign team. He won a landslide victory in his race for Lieutenant Governor in 1994, receiving more votes than any other Democratic candidate in America.[16][17] Davis ran as a moderate candidate against Republican Cathie Wright.[20] Davis used ads to depict Wright as a Republican that was too conservative for California.[18] Davis had a large advantage in campaign funds.[18]

As Lieutenant Governor until 1999, Gray Davis focused on efforts on the California economy and worked to encourage new industries to locate and expand in the state.[17] He also worked to keep college education affordable for California's middle-class families and oversaw the largest student-fee reduction in California history.[17] As the state's second-highest officeholder, he served as President of the State Senate, Chair of the Commission for Economic Development, Chair of the State Lands Commission, Regent of the University of California and Trustee of the California State University.[17]

1998 campaign for Governor

In the June primary election, Davis surprised political observers by handily defeating two better funded Democratic opponents: multimillionaire airline executive Al Checchi and Jane Harman, whose husband is a multimillionaire.[21][6] Davis's campaign slogan during the primary was "Experience Money Can't Buy." Early primary polls showed Davis in third for the Democratic nomination.[21] Davis surprised many political insiders with his landslide come from behind victory.[6][22] Davis even finished ahead of the unopposed Republican nominee in California's first blanket gubanatoral primary.

Davis won the 1998 general election for Governor with 57.9% of the vote, defeating Republican Dan Lungren who had 38.4%. Davis aimed to portray himself as a moderate centrist democract and to label Lungren a Republican too conservative for California and out of touch with its views on issues like guns and abortion.[23] After his victory, Davis declared that he would work to end the "divisive politics" of his predecessor Pete Wilson.[23] In his campaign, Davis emphasized the need to improve California's public schools, which voters had cited as their top concern in this election.[23]

First term

Popular start and education

In 1998, Davis was elected the Golden State's first Democratic governor in 16 years. The San Jose Mercury News called him "perhaps the best-trained governor-in-waiting California has ever produced."[1] Davis was strongly viewed as a possible Democratic candidate for President in 2004.[24] In March 1999, Davis enjoyed a 58% approval rating and just 12% disapproval.[25] His numbers peaked in February 2000 with 62% approval and 20% disapproval, coinciding with the peak of the dot-com boom in California.[8][26] Davis held his strong poll numbers into January 2001.

Davis's first official act as governor was to call a special session of the state legislature to address his plan for all California children to be able to read by age 9.

| “ | "I ran for governor because of my passion for education," Davis told CNN the Sunday night before the recall election on Larry King Live.[1] | ” |

Just nine months into his first term as Governor, Davis was suspended from the State Bar of California for the second time (the first time was while serving as Governor Jerry Brown's Chief of Staff).[12]

Davis used California's growing budget surplus to improve education. He signed legislation that provided for a new statewide accountability program and for the Academic Performance Index and supported the high school exit exam.[5] He signed legislation that authorized the largest expansion of the Cal Grant program.[5] Under the Davis administration, California began recognizing students for outstanding academic achievement in math and sciences on the new Golden State Exam. Davis's Governors Scholarship program provided $1,000 scholarships to those students who scored in the top 1% in two subject areas on the state's annual statewide standardize test.

Davis signed into law legislation that began the Eligibility in the Local Context (ELC) program that guaranteed admission to a UC to students that finished in the top 4% of their high school class.[27] Public schools received $8 billion over the minimum required by Proposition 98 during Davis's first term. Davis increased spending on recruiting more and better-qualified teachers. He campaigned to lower the approval threshold for local school bonds from two-thirds to 55 percent in a statewide proposition that passed. Davis earmarked $3 billion over four years for new textbooks and, between 1999 and 2004, has increased state per-pupil spending from $5,756 to $6,922.[28]

In 2001, Gov. Gray Davis signed Senate Bill 19, which establishes nutritional standards for food at elementary schools and bans the sale of carbonated beverages in elementary and middle schools.[29]

Another early act of Davis' was the reversal of his predecessor Republican Governor Pete Wilson's alteration of California's 8 hour overtime pay rule for wage earners.

Domestic partnerships

Davis recognized the domestic partnerships registry in 1999 and, in 2001, gave partners a few of the rights enjoyed by spouses such as making health care decisions for an incapacitated partner, acting as a conservator and inheriting property.[5] He also signed a bill to prevent disqualification from a jury based on sexual orientation. He signed a bill allowing employees to use family leave to care for a domestic partner though he didn't make good on his promise to convene a task force on civil unions.[28]

Guns and public safety

He signed laws in 1999 banning so-called assault weapons by characteristic rather than brand name, as well as limiting handgun purchases to one a month, requiring trigger locks with all sales of new firearms and reducing the sale of cheap handguns. Davis' ban included a ban on high-powered weapons and so-called "Saturday Night Specials."[27][5] In 2001, Davis signed a bill requiring gun buyers to pass a safety test.[28] A supporter of the death penalty and tougher sentencing laws, Davis blocked nearly all parole recommendations by the parole board.[28]

Relations with Mexico

Early in 1999, Davis sought to improve relations with Mexico. Davis believed that California under Pete Wilson had left millions of dollar of potential trade revenues "on the table."[30] Ironically, because of Davis' later hard criticisms of Bush during the energy crisis, Davis wanted California to have relations with Mexico that were more similar to Texas under then Governor George Walker Bush.[30] Controversy over the California Mexico border and California Proposition 187 had strained the relationship between the two parties.[31] Davis met with Mexican President Ernesto Zedillo to improve relations with California's southern neighbor and major trading partner within Davis' first 30 days in office.[2][5] Davis later met with President Vicente Fox and participated in his inauguration. The Governor met with Mexican Presidents eight times. Under the Davis administration, California and Baja California signed a "Memorandum of Understanding" expanding cooperation in several policy areas.[2] Under Davis, Mexico became California's leading export market for the first time in history and California's trade with Mexico surpasses all of Mexico's trade with Latin America, Europe and Asia combined.[2] Because of the growth in the California economy, Davis opened and expanded trade offices around the world, including in Mexico. But most of these offices were eliminated in 2003 California budget due to difficult fiscal times.[2]

Health, environment, business, and transportation

Davis significantly expanded number of low-income children with state-subsidized health coverage.[2] He signed laws to allow patients to get a second opinion if their HMO denies treatment and, in limited cases, the right to sue.[27] Davis signed legislation that provided HMO patients a bill of rights, including help-line to resolve disputes and independent medical review of claims.[5] Under Davis, staff-to-patient ratios in nursing homes improved. However, Davis didn't expand low-cost health care to parents of needy children due to budget constraints or prevent millions of health care dollars being returned to federal government unused.[28]

Davis allowed non-disabled low-income people with HIV to be treated under Medi-Cal. He signed a law allowing people participating in needle exchange programs to be immune from criminal prosecution. He also increased state spending on AIDS prevention.[28]

Under Governor Davis, California's anti-tobacco campaign became one of the largest and most effective in the nation.[32] R. J. Reynolds and Lorillard Tobacco sued over California's antismoking campaign but their lawsuit was dismissed in July 2003. Davis also authorized a new hard-hitting anti-smoking ad that graphically depicts the damage caused by secondhand smoke.[2]

In September 2002, Governor Davis signed bills to ensure age verification was obtained for cigarettes and other tobacco products sold over the Internet or through the mail, ensured that all state taxes are being fully paid on tobacco purchases, and increased the penalty for possessing or purchasing untaxed cigarettes.[33] He also signed legislation to expand smoke-free zones around public buildings.[33][2]

Davis approved legislation creating a telemarketing do-not-call list in 2003.[27] Under Davis, benefits for injured and unemployed workers increased. The minimum wage increased by $1 to $6.75.[2] Davis backed higher research and development tax credits. He pushed for elimination of the minimum franchise tax paid by new businesses during the first two years of operation.[28]

While Davis's record was pro environmental by increasing spending on land acquisition and maintenance of the state's park system, signing legislation that attempts to cut greenhouse gas emissions by having automakers produce more efficient vehicles, cutting fees to state parks, and opposing offshore drilling, he did not back tougher restrictions on timber companies as some environmentalists desired.[28] Under the Davis administration, California purchased 10,000 acres (40 km2) for urban parks.[5]

Davis signed the first state law in the US in July 2002 to require automakers to limit auto emissions. The law required the California Air Resources Board to obtain the "maximum feasible" cuts in greenhouse gases emitted by all non-commercial vehicles in 2009 and beyond.[34] Automakers claimed the law would lead smaller and more expensive cars sold in California.[35]

On March 25, 1999, Davis issued an executive order calling for the removal of MTBE (a toxic gasoline additive) from the state's gas.[36] In 2001, in order for gas prices to remain reasonable in California while removing MTBE, Davis asked President George W. Bush to order the EPA to grant California a waiver on the federal minimum oxygen requirement.[37] Without a waiver, California would have to import a much larger amount of ethanol per year and gas prices were projected to increase drastically. Bush did not grant the waiver, and in 2002, Davis issued an executive order reversing his earlier executive order.[38]

Davis's actions when it came to regulating business suggested that Davis was a more moderate Governor. He worked to kill a comprehensive bill opposed by banks and insurance companies to protect consumers' personal financial information. "What you saw in the campaign was what you got," said professor Bruce Cain. "He's tried to negotiate a course between the different interest groups and keep Democrats on a more centrist, business-oriented track".[28]

Davis approved $5.3 billion over five years for more than 150 transit and highway projects. One of those projects was construction on the new eastern section of the Bay Bridge. During 1999 and 2000, California spent millions on onetime projects like buying new rail cars and track improvements.[28]

Declining popularity

In May 2001, in the middle of the California electricity crisis, his numbers declined to 42% approval and 49% disapproval.[39] By December 2001, Davis' approval ratings spiked up to 51%.[40] His numbers declined back to the May 2001 level and remained about the same over the next year.[41] On April 2003, Davis had a 24% approval rating 65% disapproval rating.[42][43] Voters cited disapproval of the state's record $34.6 billion budget shortfall, growing unemployment, and dubious campaign contributor connections.

Davis had tried to maintain a middle-of-the-road approach, but ultimately alienated many of the state's liberals who viewed him as too conservative, and many conservatives who viewed him as too liberal.[44] Many were upset that in trying to balance the budget, Davis cut spending for schools while increasing spending for prisons in lieu that in the coming years, a federal court ruling would declare the conditions in California prisons so poor and overcrowded that they were unconstitutional.[45] Some critics attributed the proposal to the California Correctional Peace Officer Associations donations to Davis's re-election campaign.[5] Californians were also upset that he did not announce the record budget deficit until after his re-election.[46] Some critics accused Davis of overstating the budget deficit, so he could cut spending and raise taxes beyond what was necessary and then claim victory when the deficit cleared up.

Negative sentiment was expressed on talk radio.[47] The John and Ken Show in Los Angeles called Davis Gumby in response to his changing positions on issues, while Mr. KABC and Al Rantel (also in Los Angeles) coined the term Governor Lowbeam as a reference to his mishandling of the electricity crisis and his term as Chief of Staff for Jerry Brown, who was often mocked as Governor Moonbeam.[48] Many talk radio programs played a role in collecting signatures to force a recall election.[48][47]

California electricity deregulation crisis

Soon after taking office, Davis was able to fast-track the first power plant construction in twelve years in April 1999, but the plant did not come on line before the electricity crisis though in-state production was not the cause.[49]

According to the subsequent Federal Energy Regulatory commission's investigation and report, numerous energy trading companies, many based in Texas, such as Enron Corporation, illegally restricted their supply to the point where the spikes in power usage would cause blackouts. Rolling blackouts affecting 97,000 customers hit the San Francisco Bay area on June 14, 2000, and San Diego Gas & Electric Company filed a complaint alleging market manipulation by some energy producers in August 2000.[50] On December 7, 2000, suffering from low supply and idled power plants, the California Independent System Operator (ISO), which manages the California power grid, declared the first statewide Stage 3 power alert, meaning power reserves were below 3 percent. Rolling blackouts were avoided when the state halted two large state and federal water pumps to conserve electricity.[50]

On January 17, 2001, Davis declared a state of emergency in response to the electricity crisis. Speculators, led by Enron Corporation, were collectively making large profits while the state teetered on the edge for weeks, and finally suffered rolling blackouts on January 17 and 18.[50] Davis stepped in to buy power at highly unfavorable terms on the open market, since the California power companies were technically bankrupt and had no buying power. California agreed to pay $43 billion for power over the next 20 years.[50] Newspaper publishers sued Davis to force him to make public the details of the energy deal.[51]

During the electricity crisis, the Davis administration implemented a power conservation program that included television ads and financial incentives to reduce energy consumption. These efforts, the fear of rolling blackouts, and the increased cost of electricity resulted in a 14.1% reduction in electricity usage from June 2000 to June 2001.[50]

Gray Davis critics often charge that he did not respond properly to the crisis, while his defenders attribute the crisis solely to the corporate accounting scandals and say that Davis did all he could. Some critics on the left, such as Arianna Huffington, alleged that Davis was lulled to inaction by campaign contributions from energy producers.[52] Some of Davis' energy advisers were formerly employed by the same energy speculators who made millions from the crisis. In addition, the Democrat-controlled legislature would sometimes push Davis to act decisively by taking over power plants which were known to have been gamed and place them back under control of the utilities. Some conservatives argued that Davis signed overpriced energy contracts, employed incompetent negotiators, and refused to allow prices to rise for residences statewide much like they did in San Diego, which they argue could have given Davis more leverage against the energy traders and encouraged more conservation.[53] The electricity crisis is considered one of the major factors that lead to Davis' recall.

In a speech at UCLA on August 19, 2003, Davis apologized for being slow to act during the energy crisis, but then forcefully attacked the Houston-based energy suppliers: "I inherited the energy deregulation scheme which put us all at the mercy of the big energy producers. We got no help from the Federal government. In fact, when I was fighting Enron and the other energy companies, these same companies were sitting down with Vice President Cheney to draft a national energy strategy."[54]

When the Enron verdicts was rendered years later, convicting Enron and other companies of market manipulation, Davis responded with the following quote:

| “ | Ken Lay and Jeffrey Skilling, more than anyone, are the reason I'm talking to you now from this law firm.[8] | ” |

On November 13, 2003, shortly before leaving office, Davis officially brought the energy crisis to an end by issuing a proclamation ending the state of emergency he declared on January 17, 2001. The state of emergency allowed the state to buy electricity for the financially strapped utility companies. The emergency authority allowed Davis to order the California Energy Commission to streamline the application process for new power plants. During that time, California issued licenses to 38 new power plants, amounting to 14,365 megawatts of electricity production when completed.[2]

In 2006, the Los Angeles Times published an article that credited Davis' signing of the long term projects for preventing future blackouts and providing California a cheap supply of energy with the increasing costs of energy.[55]

In March 2003, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission's long awaited report on the so-called "energy crisis" was released. That report mostly vindicated Davis, laying the blame for the energy disruption and raiding of California's treasury on some 25 energy trading companies, most of which were based in Texas.

Budget crisis

During the economic boom years of the Davis administration, the California budget expanded to cover Davis's new programs. California's low national K-12 education rankings and Davis's campaign pledge to help education, along with the large majority that elected Davis to his first term and his early popularity, suggest that a majority of Californians supported increases in education spending during the early part of his first term when California was in budget surplus. Polls also showed that increased spending in education was supported by the California voters.[56] Under the Davis administration, taxes were cut by over $5.1 billion that included a $3.5 billion cut in sales tax and a reduction in the vehicle licensing fees.[27][57] The cut in sales taxes was mandated due to a 1991 law that required sales taxes to be reduced a quarter percent when budget reserves exceed 4 percent of the state general fund for two straight fiscal years which they did in 1999 and 2000.[57] Davis also vetoed $5.1 billion in appropriations during that span.[57]

While California's economy was expanding, California was producing record budget surpluses under Davis even after his tax cuts and new spending. According to the California Department of Finance, California had a 10% surplus at the end of 1999 and California was projected to have a 4% surplus at the end fiscal year 2000.[57] These surplus monies were left in the treasury. Davis claimed to be cautious with state finances.

| “ | "I’m trying to chart a prudent course and keep us somewhere in the middle. I don’t want to jump the gun on spending; I don’t want to jump the gun on tax relief," said Davis concerning the budget surpluses on October 26, 2000.[57] | ” |

Then, the dot-com boom that had been fueling California's record tax revenues burst unexpectedly because of the large number of high tech firms in California and California's dependence on state income taxes. Because of the loss of state revenue associated with Proposition 13, California became more dependent on state income taxes. When the dot-com boom turned to bust, state revenues fell while ongoing spending commitments created deficits. Restoring the licensing fees to pre tax cut levels to close the budget gap and stabilize the state's credit rating became unpopular.[8][58] The beginning shortfall for the 2002-2003 state budget was $23.6 billion.[59] Davis announced that the 2003-2004 budget shortfall would be $34.6 billion while the Legislative Analyist projected a $21.1.[60]

2002 reelection

Davis began fundraising for his 2002 reelection campaign early in his governorship. Davis raised $13.2 million in 1999 and $14.2 million in 2000, both unprecedented sums at the time so early in an elected term.[61] Davis's 1999 and 2000 contributions included contributions from Pacific Gas & Electric and Edison International.[61] Davis also received large contributions from labor groups, environmental groups, and individuals.[61]

Davis' fundraising efforts attracted much attention. University of California Berkeley's Institute of Government Studies claimed that Davis' fundraising skills were "second to none in the political arena" while Senator John McCain called Davis' 2001 goal of $26 million "disgraceful."[62] One article in the San Francisco Chronicle claimed that Davis was raising $34,000 a day.[63] Although Davis' fundraising pace was criticized by his many detractors, Arnold Schwarzenegger would later collect contributions at a quicker rate during the early years of his governorship.[64] Now Arnoldwatch.org, a project of the Foundation for Taxpayer and Consumer Rights which is a nonpartisan organization that is critical of both Democrats and Republicans, called Davis a "pay to play" politician and a "sellout".[65]

During the 2002 election campaign, Davis took the unusual step of taking out campaign ads during the Republican primaries against Los Angeles mayor Richard Riordan. Davis claimed that Riordan had attacked his record and that his campaign was defending his record.[66] Polls showed that, as a moderate, Riordan would be a more formidable challenger in the general election than a conservative candidate. Polls even showed that Riordan would defeat Davis.[67] Davis attacked Riordian with negative ads in the primary. The ads questioned Riordan's pro-choice stance by questioning Riordan's support of pro-life politicians and judges.[68][69] The ads pointed out Riordan's position of wanting a moratorium on the death penalty as being to the left of Gray Davis, who strongly supported it.[70][71][72]

Davis' negative ads against Riordan and a variety of other equally important factors explained on the 2002 election page, lead to Riordan's defeat in the Republican primary by the more staunchly conservative candidate Bill Simon. In the first 10 weeks of 2002, Davis spent $10 million on ad: $3 million on positive ads boasting of his record, $7 million on negative ads against Riordan.[73]

Davis was re-elected in the November 2002 general election following a long and bitter campaign against Simon, marked by accusations of ethical lapses on both sides and widespread voter apathy.[74] Simon was also hurt by a financial fraud scandal that tarnished Simon's reputation.[75] Davis campaign touted California's improving test scores, environmental protection, health insurance coverage for children, and lower prescription drug costs for seniors.[76] Davis's campaign featured several negative ads that highlighted Simon's financial fraud scandal.[77] The 2002 gubernatorial race was the most expensive in California state history with over $100 million spent.[78] Davis's campaign was better financed; Davis had over $26 in campaign reserves more than Simon in August 2006.[77] Davis gained re-election with 47.4% of the vote to Simon's 42.4%. However, the Simon-Davis race led in the lowest turnout percentage in modern gubernatorial history, allowing a lower than normal amount of signatures required for a recall.[79] Davis won the election but majority of the voters disliked Davis and did not approve of his job performance.[80][81]

Other challenges

While polls attributed Davis's declining popularity to the energy and budget problems, some newspaper articles and commentators have identified other issues of his tenure that limited his effectiveness and political appeal. Davis had some trouble in his relations with the California legislature. There were disagreements between the more moderate Davis and the more liberal Democrat-controlled Legislature.[28] Democrat John L. Burton, the leader of the California State Senate, was Davis' chief antagonist.[28] In 2003, Republican leader Jim Brulte told The Los Angeles Times that Davis lacked the basics of political collegiality to pull him through hard times. "I never felt I got to know him ... I always felt a little sorry for him".[29]

Davis's moderate record made it difficult for him to appeal to any core constituency of the Democratic Party. During the recall, Davis failed to gain the full support he needed from his more liberal Democratic base.[16] He got the reputation of being beholden to supporters and unable to satisfy them.[29]

Davis's leadership and compromise building skills have also been questioned. Many of the challenges that California faced during his years required a strong force of personality to forge compromise but Davis lacked such skill.[29] He was also hurt by redistricting in 2000 that made most districts safe for the incumbent party, limiting some legislators need and willingness to compromise.[29]

Davis's personality was often reported to be aloof and his political style cautious and calculated instead of charismatic and someone the voters and those who worked with him could identify.[16] His personality caused him to depend more on political skill such as fundraising to win elections.[16] Davis's management style and his tendency to micromanage his administration drove people out of his administration and made it difficult for people to present opposing views.[51]

As Davis left office in 2003, the San Francisco Chronicle published an editorial discussing his legacy. The newspaper claimed that he lacked vision, allowing the legislature and its policies to define his tenure, and focused on "robotic governing style" that focused on fundraising instead of personal relationships. The Chronicle commented that Davis was often on the right side of the issues but that being on the right side of the issues alienated the electorate. Davis lacked the charisma and seemed to be more passionate about winning campaigns than governing.[16] Davis never revealed emotion to the voters.[82] He often could only spend time on his campaigns talking about his accomplishments instead of providing the voters with a vision.[5]

Second term

Davis's second term, which lasted only ten months, was dominated by the recall election. Davis signed into law several controversial measures during the closing weeks of the recall campaign, including one granting drivers' licenses to illegal immigrants. Davis also signed legislation requiring employers to pay for medical insurance for workers and legislation granting domestic partners many of the same rights as married people. He vetoed legislation giving illegal immigrants free tuition for community college. Many of Davis's opponents were furious over the signings of these measures during the final weeks of the Davis administration.[83] Some political observers say these efforts as an attempt to re-enforce support from Hispanics, labor union members, and liberal wing Democrats.[83] Ultimately, Davis did not have as much support from Hispanics and union members in the recall election as he did in his 2002 re-election.[16]

Davis was Governor during the southern California fires of 2003 more commonly known as the Cedar Fire. Davis declared a state of emergency in Los Angeles County, San Bernardino County, San Diego County, and Ventura County in October 2003 and deployed the national guard to help in disaster relief. By mid November, the greater South Los Angeles area had been declared a disaster area to help the area cope with flooding and weather related damage due to the fires destroying thousands of acres of vegetation.[84] The Cedar Fire was Davis' last major event during his tenure as Governor. With Schwarzenegger as the Governor elect, both Davis and Schwarzenegger worked to help in disaster relief. Schwarzenegger went to Washington, D.C. and met Vice President Dick Cheney to lobby the federal government for more disaster relief funds.

Recall

In July 2003, a sufficient number of citizen signatures were collected for a recall election. The initial drive for the recall was fueled by funds from the personal fortune of U.S. Rep. Darrell Issa, a Republican who originally hoped to replace Davis himself. The 2003 California recall special election constituted the first gubernatorial recall in Californian history, and only the second in U.S. history.

Early in the recall election, Davis called the recall election an “insult” to the eight million voters who had voted in the 2002 gubernatorial election.[85] The Davis campaign tried to run against the recall Yes/No vote instead of against the candidates that were trying to replace him.[22] Davis tried to depict the recall as a $66 million waste of money that could allow a candidate with a very small percentage of the vote to become Governor—potentially someone who was very liberal or conservative.[22] There are no primaries in a recall election. Davis tried to run “outside the recall circus” and to make himself appear gubernatorial and hard at work for California, who had made improvements to education and healthcare.[22][86] Early August polls showed that over 50% supported the recall.[22]

In September 2003, Davis conceded that he had lost touch with the voters and he was trying to correct that with numerous townhall meetings.[24] Poll numbers in September showed a 3% drop in the number of California voters who were planning to vote yes on the recall.[87] According to some analysts and campaign aides, Davis's town hall meetings and conversations with voters were softening his image.[87] Many political insiders remarked that Davis had made several comebacks and that he should not be counted out of the race despite poll numbers that showed over 50% planning to vote yes on the recall.[87][22][6]

During the recall, Davis blamed some of the state's problems on his predecessor Pete Wilson.[88] Davis claimed that he would have rather raised taxes on the upper tax brackets instead of restoring vehicle registration fees and college student tuition.[88] California law requires legislation that raises taxes to gain a 2/3 majority in the legislature. Davis could not gain that majority in the California legislature because that majority would require many Republican votes. The Republican members were firmly against any such tax increases, while raising fees only require a simple majority in the legislature.

Davis tried to define the recall as a right-wing effort to rewrite history after losing the fall election last year.[88] In a major 19 minute campaign address that was broadcast statewide, Davis called the recall a "right-wing power grab" by Republicans and he blamed Republicans in the legislature and in Washington for many of the states problems while at the same time he tried to take some of the responsibility for the states' problems.[89]

| “ | "It's like the Oakland Raiders saying to Tampa Bay, 'We know you beat us, but we want to play the Super Bowl again,"' said Davis about the recall.[88] | ” |

On October 7, 2003, Davis was recalled with 55.4% of the votes in favor of the recall, and Republican Arnold Schwarzenegger was elected to replace him as governor. The Bay Area was the only region in California to vote no on the recall: San Francisco rejected the recall by a 4 to 1 ratio.[90] Davis joined Lynn Frazier of North Dakota, who was ousted in 1921, as the only governors in American history to be recalled.[90] His final full day in office was November 16, 2003.[91]

On the night of the recall, Davis conceded defeat and thanked California for having elected him in 5 statewide elections. Davis mentioned what he defined as the accomplishments of his administration such as improvements in education, environmental protection, and health insurance for children.[92] Davis said he would help Schwarzenegger in the transition and he later urged his staff to do the same.[93]

Life after politics

After leaving public office, Davis appeared on several shows, such as The Tonight Show with Jay Leno and The Late Show with David Letterman, as well as a cameo as himself on CBS sitcom Yes, Dear. In December 2004, he announced that he was joining the law firm of Loeb & Loeb.

Davis spends 80% of his workdays practicing corporate law as "of counsel" to Loeb & Loeb in Century City, a firm where all attorneys wear casual attire, even Davis. American Lawyer magazine called the firm one of "best places" in the country to work.[8]

Davis has done several media interviews about his legacy. He appeared prominently in the documentary Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room.[94]

The debate about his legacy and role regarding the energy woes that proved to be his downfall remains. Davis feels complete vindication because of the revelation that Enron manipulated the California energy market and because of Schwarzenegger's (then) low approval ratings.[94] In a CNN interview on August 5, 2005, Davis said that he had no interest in running for Governor again, although he had been urged to run by some Democrats.

He was a guest lecturer at UCLA's School of Public Policy in 2006 alongside former Republican State Senator Jim Brulte. He wrote an introduction for a journalist's book on the Amber Alert system for missing children, a cause he championed.[8]

On April 23, 2007, Davis was appointed to the Board of Directors of animation company DiC Entertainment, as a non-executive.[95]

References=

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Davis: A shining resume, a resounding defeat from CNN.com, Wednesday October 8, 2004. Accessed September 8, 2007.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 Davis Digital Library, Accomplishments

- ↑ Headlines in search show improved relations

- ↑ Davis Loyalists Give Cruz Cold Shoulder by Ballon, Marc. JewishJournal.com. Copyright 2006-2007. Accessed September 17, 2007.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 5.9 STATE OF TRANSITION: End of the Davis era, Tempered temperament led state by Salladay, Robert The San Francisco Chronicle. Wednesday, November 12, 2003. Accessed on August 22, 2007.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 Chorneau, Tom. “Davis’ career one of survival despite long odds.” Associated Press State & Local Wire. Wednesday, September 10, 2003. Copyright 2003 Associated Press. Accessed on LexisNexis on August 11, 2007.

- ↑ Full Biography for Gray Davis, November 5, 2002 Election Created by the candidates. League of Women Voters of California Education Fund. Accessed August 22, 2007

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Bright Days for Gray Davis by Balzar, John. The Los Angeles Times

- ↑ Schwarzenegger Talks Economics CNN

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Interview with Gray Davis Part I

- ↑ California Governors Biography

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 California State Bar - Joseph Graham Davis, Jr. Attorney Record

- ↑ Interview with Gray Davis Part II

- ↑ Davis Has Auditioned 23 Years for Governorship

- ↑ The New Governors. The Washington Post. Thursday, November 5, 1998; Page A41. Accessed on September 8, 2007.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 16.7 16.8 Chorneau, Tom. “Gray Davis’s downfall rooted in his personality and political style.” The Associated Press State & Local Wire. October 9, 2003. Copyrighted 2003 Associated Press. Accessed on LexisNexis August 10, 2007

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 Full Biography for Davis League of Women Voters of California. Accessed on September 7, 2007.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 The Race for Lieutenant Governor: Democrat Gray Davis and Republican Cathie Wright vie to serve a heartbeat away by Borland, John. The California Journal. Copyright California Voter Foundation 1994. Accessed on September 7, 2007.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Chorneau, Tom. “Feinstein takes on role as Davis’ chief defender.” Associated Press State & Local Wire. September 3, 2003. Copyright 2003 Associated Press. Accessed on LexisNexis on August 11, 2007.

- ↑ Calvoter.org Information

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 California Governor's Race Gets Tougher: Open primary makes it the most unpredictable contest in the nation by Schneider, Bill. CNN.com. Copyright © 1998 AllPolitics. March 3, 1998. Accessed on September 7, 2007.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 Chorneau, Tom. “Davis campaign to run outside recall circus.” Associated Press State & Local Wire. Tuesday, August 12, 2003. Copyright 2003 Associated Press. Accessed on LexisNexis on August 11, 2007.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 In Key State of California, Democrats Bask in Victories by Booth, William & Sanchez, Rene. The Washington Post. Wednesday, November 4, 1998; Page A29. Accessed on September 7, 2007.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Davis concedes he had lost touch with voters by Salladay, Robert & Coile, Zachary. The San Francisco Chronicle. Thursday, September 18, 2003. Accessed on September 7, 2007.

- ↑ Voters Well Pleased With Governor's First 100 Days, Poll Finds 5-to-1 approval ratings put Davis on solid footing out of the gate by Marinucci, Carla. The San Francisco Chronicle. March 19, 1999. Accessed on September 7, 2007.

- ↑ Record-High Job Ratings for California Politicians by Gledhill, Lynda. The San Francisco Chronicle. February 16, 2000. Accessed September 7, 2007.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 Davis First's Accessed August 2007.

- ↑ 28.00 28.01 28.02 28.03 28.04 28.05 28.06 28.07 28.08 28.09 28.10 28.11 Energy crisis leaves Davis record in dark by Lucas, Greg. The San Francisco Chronicle. October 13, 2002. News, pg A1. The Chronicle Publishing Company 2002. Accessed July 23, 2007.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 San Diego conference tackles child obesity epidemic by Yang, Sarah. January 2, 2003. Media Relations. University of California Berkeley Press Release. Copyright 2002 UC Regents.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Stats belie Davis claim on trade with Mexico

- ↑ Davis to Meet Mexican Leader Twice a Year Fox arrives to inaugurate new cross-border Net link

- ↑ California Connected Education

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Tobacco Control Legislation

- ↑ Topics: State and Local Action. California Governor Gray Davis Signs Landmark Law Designed to Cut Car Exhaust Emissions from Climate.org. July 2002. Accessed September 3, 2007.

- ↑ The law still faces legal challenges and must be granted a waiver by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). California's emission-control law upheld on 1st test in U.S. court

- ↑ Timeline for Phase Out of MTBE

- ↑ GOVERNOR DAVIS URGES FEDS TO GRANT CALIFORNIA'S REQUEST FOR OXYGENATE WAIVER

- ↑ Davis Executive Order

- ↑ State gives president tepid ratings Power crisis blamed for 42% approval

- ↑ Riordan has edge on Davis in polls Governor's mixed reviews seen to benefit challenger

- ↑ Davis unpopular, but a bit less so Democrats, independents more supportive in past months, poll says

- ↑ Govs Under The Gun

- ↑ A Profile of California Gov. Gray Davis

- ↑ Liberal voters souring on Davis Labor, women, death penalty foes wonder: Is this guy really a Democrat?

- ↑ Judges Consider Cap on California Prison Population

- ↑ Did Davis hide extent of fiscal crisis in 2002?

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Press Junket to "Happy Iraq" - Journalism or Propaganda?

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 The John And Ken Show Roils California’s Congressional Republicans

- ↑ Turning On The Juices Rush to build power plants must balance demand with environmental, community concerns

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 50.3 50.4 Highest Energy Alert: STAGE 3 EMERGENCY Rolling blackouts narrowly averted by shutting down huge pumps

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Governor's Race Gray Davis Energy crisis grew into ball and chain by Glendhill, Lynda. The San Francisco Chronicle. Sunday, February 17, 2002. Accessed on August 14, 2007.

- ↑ Gov. Davis and the failure of power

- ↑ Ten good reasons to recall Gray Davis

- ↑ Contentious Davis blasts GOP 'power grab'

- ↑ Little risk to Schwarzenegger of blackouts, thanks to Gray Davis by Kurtzman, Laura. Associated Press. Posted on Fri, Jul. 21, 2006. Accessed on August 14, 2007.

- ↑ Californians Like Idea Of Cutting Class Size Longer school year comes in 2nd, poll finds

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 57.3 57.4 $1.1 billion sales tax cut announced by Davis

- ↑ State credit rating gets downgraded by Moody's Agency criticizes governor's lowering of vehicle license fee

- ↑ No budget relief ahead, state Senate leader says

- ↑ Overview of the Governor’s Budget

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 Gladstone, Mark. "California Governor Raises Record Funding for Campaign." San Jose Mercury. February 2, 2001. Copyright 2001 News Knight Ridder/Tribune Business News. Accessed from LexisNexus July 22, 2007.

- ↑ Political Fundraising of Governor Gray Davis by Staff of Institute of Government Studies. University of California Berkeley. Accessed on August 13, 2007.

- ↑ Political Fundraising of Governor Gray Davisby Staff of Institute of Government Studies. University of California Berkeley. Accessed on August 13, 2007.

- ↑ Schwarzenegger outpacing Davis in fundraising by Hinch, Jim. Orange County Register. December 24, 2003.

- ↑ The Gray Davis Files by Arnoldwatch.org. "The Gray Davis Files."]

- ↑ 'Fight' seen in California's governor's race

- ↑ Riordan has edge on Davis in polls Governor's mixed reviews seen to benefit challenger

- ↑ Davis ad assails Riordan GOP rival's stand on abortion rights challenged

- ↑ Riordan silent on abortion flap Davis ad hits GOP governor hopeful for giving to thousands to anti-choice groups

- ↑ Top GOP governor candidates trade attacks Surveys show Simon closing in on Riordan's once imposing primary lead

- ↑ Kevin Cooper Awaits DNA Test Results

- ↑ A man for all reasons

- ↑ What happens in the eight months until California's general election?

- ↑ Davis, Simon heartily disliked Voter disenchantment has soared to unprecedented level, poll says

- ↑ Gray Davis from Economist.com.

- ↑ Governor’s race features diverse views: Gray Davis

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Turns up heat as Simon pares down: New ads roast GOP rival as he trims staff by Carla Marinucci, Lynda Gledhill, Chronicle Staff Writers. The San Francisco Chronicle. Friday, August 16, 2002.

- ↑ Cal Voter

- ↑ Polling in the Governor's Race in California

- ↑ Davis ekes out 7-point lead over Simon Field Poll shows voters against hopeful rather than for governor

- ↑ Big challenges ahead for not-exactly-popular incumbent

- ↑ San Francisco Chronicle Editorial Board. "Gray Davis' Legacy." San Francisco Chronicle. November 17, 2003. Pg. A20. Accessed on Lexis Nexis August 10, 2007.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 State Net California Journal. "From the Floor - Gray Davis' final acts." Copyright 2003 State Net(R). November 1, 2003, Saturday. Vol. 55, Iss. no. 11, Pg. 40. Accessed on LexisNexis August 10, 2007.

- ↑ City News Service. "Gov. Grady Davis Declares State of Emergency in South Los Angeles." Friday, November 14, 2003. Copyright 2003 News Service Inc. Accessed on LexisNexis August 10, 2007.

- ↑ Chorneau, Tom. “Davis calls recall an 'insult' to his supporters.” Associated Press State & Local Wire. August 11, 2003, Monday. Copyright 2003 Associated Press. Accessed on LexisNexis on August 11, 2007.

- ↑ nterview With California Governor Gray Davis, Wife Sharon Davis

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 87.2 Chorneau, Tom. “Campaign midpoint offers Davis last chance.” Associated Press State & Local Wire. Tuesday, September 9, 2003. Copyright 2003 Associated Press. Accessed on LexisNexis on August 11, 2007.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 88.2 88.3 Chorneau, Tom. “Davis defends job and says he’ll stay in touch with the people.” Associated Press State & Local Wire. Wednesday, September 3, 2003. Copyright 2003 Associated Press. Accessed on LexisNexis on August 11, 2007.

- ↑ Contentious Davis blasts GOP 'power grab' PIVOTAL ADDRESS: Governor appeals to his base

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 SCHWARZENEGGER LEADS VOTER REVOLT Davis recalled; turnout is huge Victory margin provides mandate

- ↑ NPR: California Gov. Gray Davis' Legacy

- ↑ Davis in defeat: 'We'll have better nights to come' Concession speech transcript.

- ↑ Davis extols accomplishments, praises aides.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 Gray Davis, Reanimated. CNN, August 8, 2005]

- ↑ DIC Entertainment Appoints Former Governor of California Gray Davis to Board of Directors (2007, April 23). Yahoo! Finance. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- ↑ [1] Dailykos.com Diary Entry July 20, 2008]

External links

- Gray Davis Digital Library (active web site, launched 2006)

- Gray Davis's Web site as Governor (from the Internet Archive)

- Gray Davis at the Internet Movie Database

- lnterview With California Governor Gray Davis, Wife Sharon Davis

- Department of Energy article on Davis's energy conservation efforts

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Edwin Meese (Chief of Staff for Governor Reagan) |

Chief of Staff for Governor Brown 1974–1981 |

Succeeded by B. T. Collins |

| Preceded by Howard Berman |

California State Assemblyman, 43rd District 1982–1986 |

Succeeded by Terry Friedman |

| Preceded by Kenneth Cory |

California State Controller 1987–1995 |

Succeeded by Kathleen Connell |

| Preceded by Leo T. McCarthy |

Lieutenant Governor of California 1995–1999 |

Succeeded by Cruz Bustamante |

| Preceded by Peter B. Wilson |

Governor of California 1999–2003 |

Succeeded by Arnold Schwarzenegger |

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Davis, Gray |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Davis, Joseph Graham, Jr. (full name) |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | California politician |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 26, 1942 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | New York City, New York |

| DATE OF DEATH | living |

| PLACE OF DEATH | |